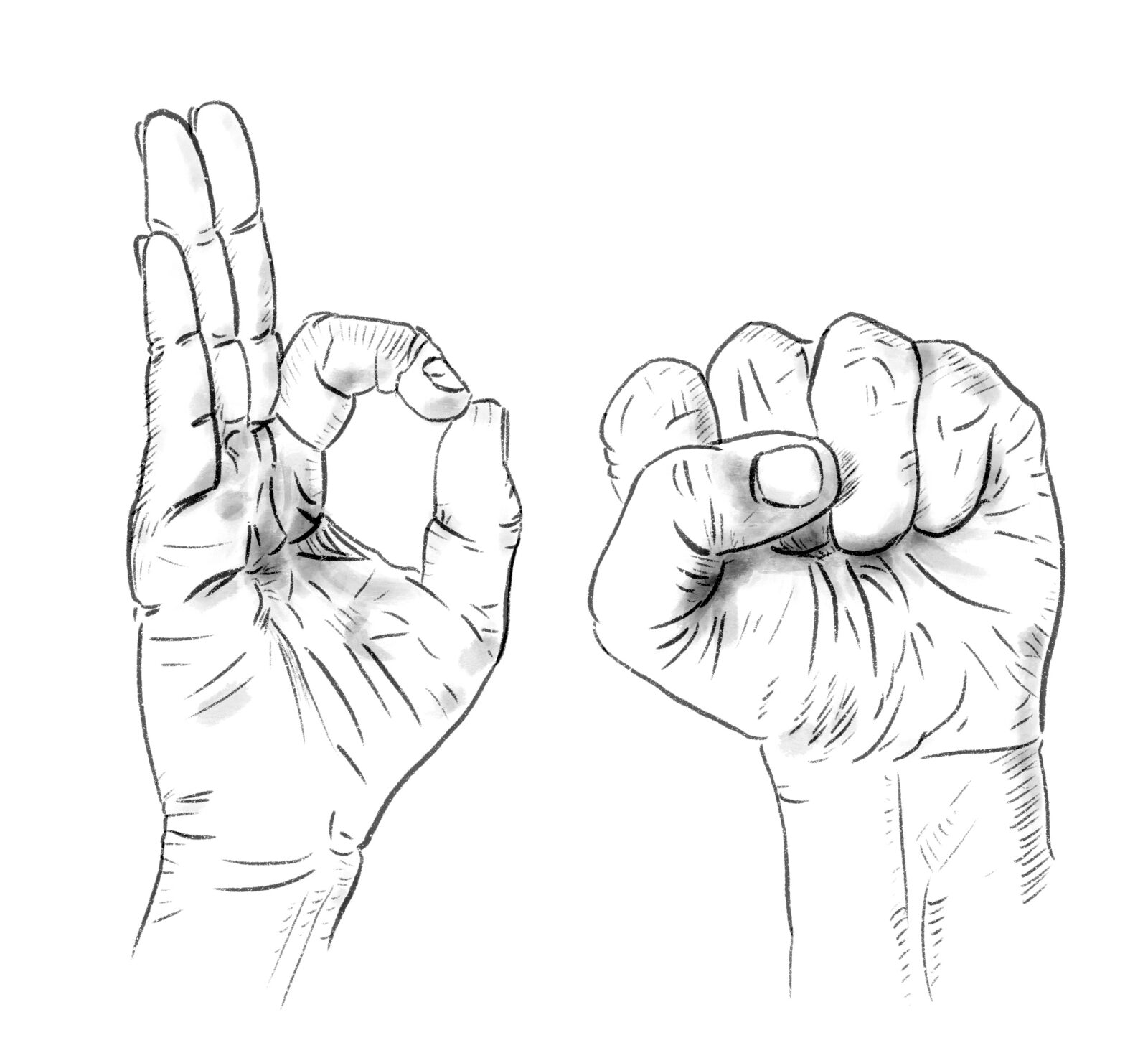

Illustration by Scott Norton

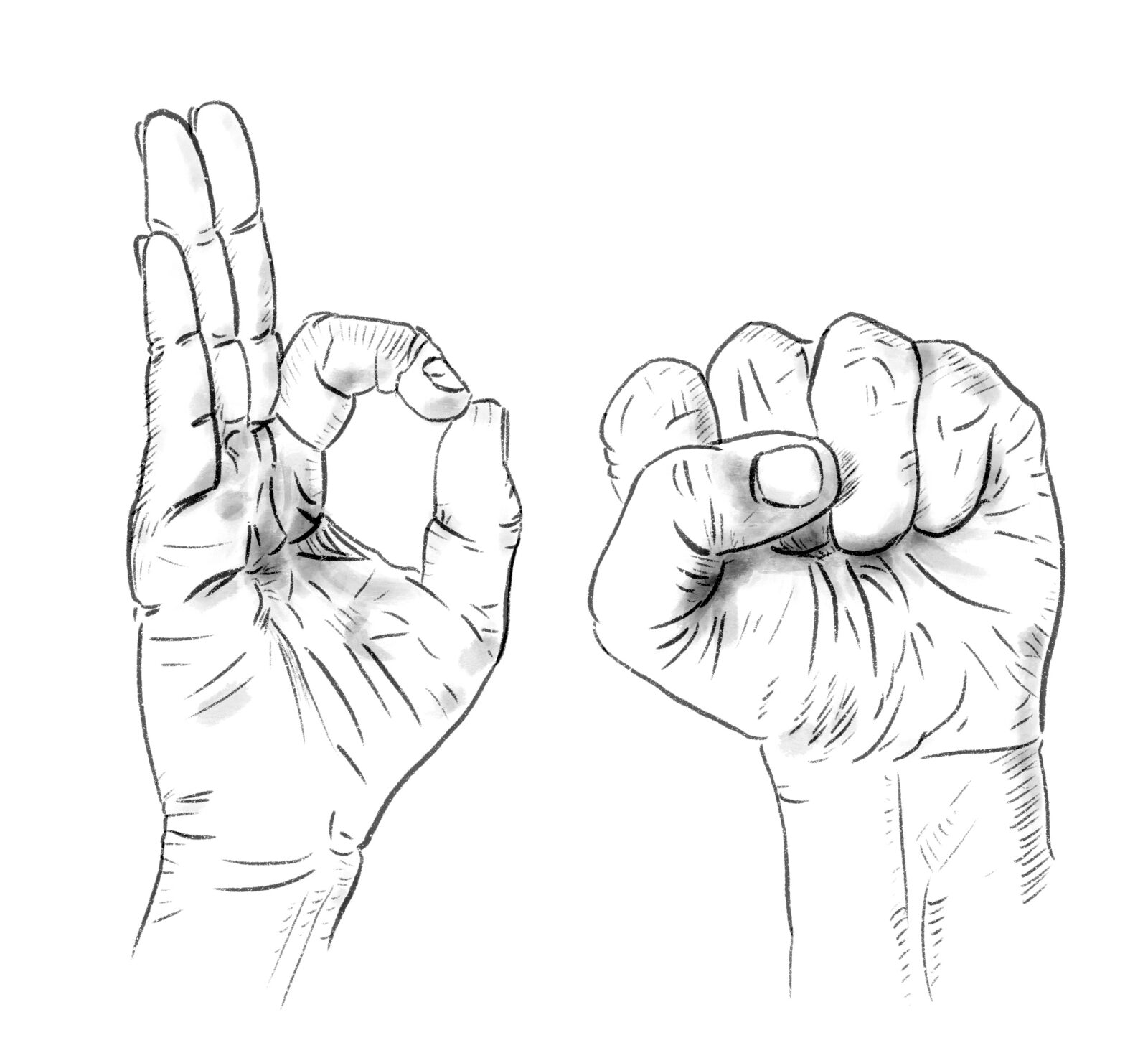

Illustration by Scott Norton

What I hear most often in the voices of new meditators is a longing to feel really here for this life, to be 100% awake for it. They have a vague sense of sleepwalking through their days, not really feeling what’s happening while it’s happening, being mentally consumed with a past they can’t change and a future they can’t foresee. They express bewilderment in the face of the present moment, having somehow missed the subtle shifts that led up to the current state of affairs. They find themselves blinking in the glare of current reality, wondering, How did I get here? How did we collectively get here? And when “here” is a state of suffering, How do we get to a better place? This longing—to be present, to be clear, to be fully awake in every moment and empowered to shape the future—is a kind of awakening in itself. We are awake to the fact that we are going through the motions of our life, we are awake to the fact that we don’t want to be, and we are aware that waking up is a critical juncture in the path that leads to happiness, wholeness, and freedom.

In contemporary interpretations of the Buddha’s teachings, the words awakening, enlightenment, and liberation are often used interchangeably to describe the goal of mindfulness and meditation practices. But more and more, I’m convinced that we have to wake up before we can be free. Awakening is the cause, and liberation is the natural effect of being awake in the world.

The difficult part about waking up is that when we awaken today, we wake up to a world that is full of suffering and inequity. That’s not all that there is, but it definitely exists. For those of us who live lives of relative privilege and comfort, being confronted with this reality can be jarring. It can make us want to close our eyes and turn away.

This was exactly my path. I thought I was coming to meditation because politics hurt too much. Local, national, and global governments and their shady dealings in business and civil society seemed overwhelming in their disfunction. Racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism—ALL of the -isms and the -obias that showed up on the world stage also showed up in my work relationships, friendships, and romantic partnerships.

I thought I needed a refuge from the troubles of the world. What I got was a refuge where I could process the troubles of the world, a place where I could cultivate enough well-being to reengage with it. Sitting in the quiet of the meditation hall, my mind got much, much louder before it ever got quiet.

Dynamics of internalized privilege and oppression often masquerade as experiences we think of as intensely personal and unrelated to politics. A sense of separation. Restlessness, doubt, and fear. Craving for comfort. Irritation when what little comfort we have is disturbed. But the longer we stay with what feels like our personal experience, the more we can see that these experiences are microcosmic manifestations of the greed, hatred, and delusion that underscore what Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called the “three giant triplets” of “capitalism, materialism, and racism.”

Many Buddhist teachers and scholars describe disillusionment, and even disgust, as a stage of insight on the path to liberation. They often identify it as the outcome of awakening into the truth of impermanence, the soul-level realization that every conditioned phenomenon in this world, including our own bodies, are subject to death and decay. A natural response to this realization is to become disenchanted with the stuff of this world.

In my own practice and teaching, I’ve seen disillusionment occur as a stage of insight into the dynamics of privilege and oppression. If our mindfulness practice includes attention to the suffering of the world and an investigation of its causes, that exploration will inevitably lead us to question the systems that result in those conditions and the mental models that power them. If our mindfulness practice includes a patient awareness of our own thoughts, emotions, and body sensations that arise in relation to people we perceive as different from us, they will inevitably lead us face to face with the degree to which we have internalized those same systems. These awakenings are not just a side effect of spiritual practice—they are the very point of spiritual practice. For some of us, they are the way in to a liberating awareness of the truth of our interdependence and recognition that happiness and freedom are inherently collective endeavors.

We have to wake up before we can be liberated from the dynamics of privilege and oppression that live inside of us and before we can liberate ourselves from participating in the systems that perpetuate privilege and oppression in our world. The good news is that once we do the hard work of waking up—of noticing what is happening inside and around us moment by moment, of knowing our relationship to it, and of using our power to change—liberation is kind of inevitable.

In the process of waking up to the truth of institutionalized power, we may fear that our hearts will break, and we will be right. They will break open, and we will be radically transformed. We will find that we have access to a power much greater than the power that systemic privilege affords us. It is a power that can drive us toward profound change.

Kate Johnson works at the intersections of spiritual practice, social action, and creativity. She has been practicing Buddhist meditation in the Western Insight/Theravada tradition since her early twenties and is empowered to teach through Spirit Rock Meditation Center. She holds a BFA in dance from the Alvin Ailey School/Fordham University, and MA in performance studies from NYU.

Kate is a core faculty member of MIT’s Presencing Institute, and has trained hundreds of leaders and change-makers in using Social Presencing Theater, a mindfulness and dance improvisation methodology used to inform strategic planning and systems change in our complex world.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.