Taryn Simon (b. New York, NY; lives and works in New York City); Chapter I from A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII; 2011; pigmented inkjet prints; 84 × 118¾ in. (213.4 × 301.6 cm); © Taryn Simon; image courtesy of the artist.

Taryn Simon (b. New York, NY; lives and works in New York City); Chapter I from A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII; 2011; pigmented inkjet prints; 84 × 118¾ in. (213.4 × 301.6 cm); © Taryn Simon; image courtesy of the artist.

“A man sets out to draw the world. As the years go by, he peoples a space with images of provinces, kingdoms, mountains, bays, ships, islands, fishes, rooms, instruments, stars, horses, and individuals. A short time before he dies, he discovers that the patient labyrinth of lines traces the lineaments of his own face.”

—Jorge Luis Borges

Portrait of the Szeiman (Simon) Family in Belarus; 1916; courtesy of Taryn Simon

A framed family portrait from over one hundred years ago hangs in Taryn Simon’s studio. The artist’s paternal grandfather, Albert Szeiman, at seven years old—seated in a wicker chair in the front left—is the youngest of the ten children. The family sat for this photograph in Belarus in 1916. Family stories and official immigration documents reconstruct the history of Simon’s grandfather, whose name was changed at Ellis Island.

The photographic form, the family’s dress, and the studio furniture testify to a time passed without return. Siegfried Kracauer defined photography as a presentation of time: “Photography provides a space-continuum . . . historical reality is grasped when they have completely re-constituted the succession of events in their temporary sequence.”1

Walter Benjamin believed everything in the early pictures was made to last: “The groupings in which the subjects came together and the garment folds in these pictures last longer.”2 This was the time of the popular photographic album. The album would be displayed on a pedestal table, leather bound, embossed with metal mounts, and gold-edged, with thick pages featuring well-dressed figures with lace collars.3 The earlier plates were far less sensitive to light and required long exposure, so the subjects had to remain still. Benjamin wrote, “They had an aura about them, a medium which mingled with their manner of looking and gave them a plenitude and security.”4

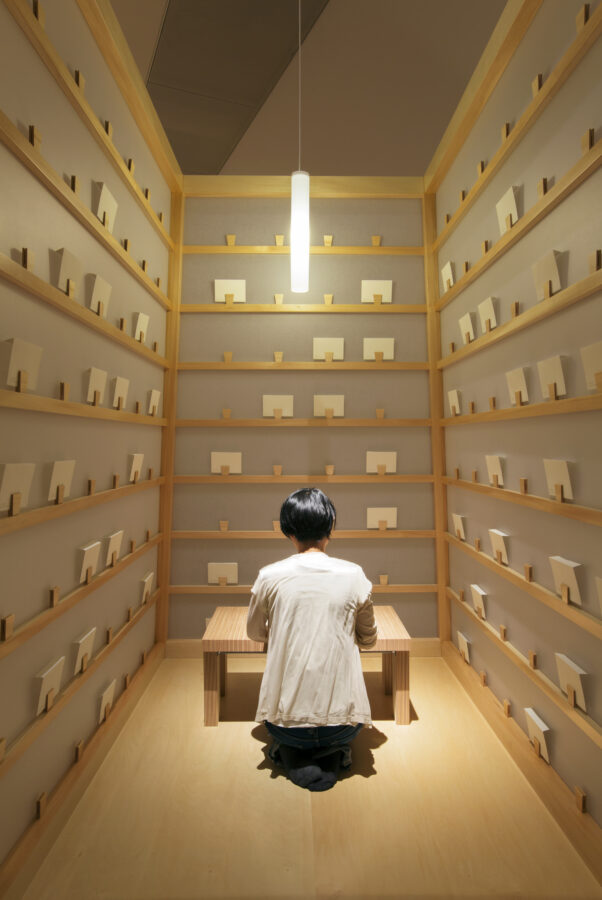

Simon’s early exposure to data collection and image making came from her grandfather’s and father’s interest in collecting, researching, and consuming scientific and cultural images of the world and the cosmos. In A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I-XVIII (2011), she produced a catalog of human survival and existence. The artist spent four years traveling around the world researching and recording eighteen bloodlines shaped by geography, power, circumstance, and fate.

Simon photographed living ascendants and descendants of a single person or animal. Each portrait of a particular bloodline is presented via three elements: individual portraits set against a uniform blank background; a text panel in scroll-like form documenting the narrative at stake; and a “footnote panel” presenting fragments of the narrative as well as adjacent stories. Among others, Simon documented living individuals in India who were declared dead to interrupt the hereditary transfer of land; the bloodline of the body double of Uday Hussein; a bloodline interrupted by the Srebrenica massacre in Bosnia; and members of a Druze family from Lebanon who attest to memories of past lives. Homi Bhabha describes Simon’s process of tracing through the bloodlines circumstances of loss, fate, disappearance, and repetition as occurring in the “continual looping of the past-in-present.”5

A Living Man Declared Dead draws from years of research and a large collection of images, whose narrative emerges from graphic design, systematic organization, and text. The uniform non-place background of A Living Man Declared Dead directs the viewer’s attention to the sitter, who becomes the subject of displacement. In the words of Bhabha, the subjects then “participate in the ambiguity of their photographic representations.”6

The Belarus family portrait, in contrast, demonstrates the careful staging of the family hierarchy and studio atmosphere. Whereas this family portrait posits the mimetic image as a straightforward record of the members of the Simon family in 1916, according to Bhabha, A Living Man Declared Dead resituates photography in another “representational or narrative medium—be it history, fiction, literary narrative, cinematic form, biography.”7

Weaving together portraits, landscapes, texts, and artifacts, A Living Man Declared Dead functions as a living memorial. Surpassing the tradition of collecting, mapping, patterning, and archiving images, Simon proposes a new language and system for mapping blood, time, and narrative.

Taryn Simon’s work was on view in the exhibition Measure Your Existence, which was on view at the Rubin Museum from February 7 to August 20, 2020.

1. Siegfried Kracauer, The Past’s Threshold: Essays on Photography, eds. Philippe Despoix and Maria Zinfert, trans. Conor Joyce (Zurich-Berlin: Diaphanes, 2014), 29.

2. Walter Benjamin, “A Short History of Photography,” Screen 13, no. 1 (1972): 17. Originally published in Literarische Welt, September 18, September 25, and October 2, 1931

3. Benjamin, 18.

4. Benjamin, 18.

5. Homi Bhabha, “Beyond Photography,” in A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I-XVIII (Berlin: Nationalgalerie Staaliche Museen zu Berlin, 2011-12), 18.

6. Bhabha, 3.

7. Bhabha, 7.

Christine Starkman is a contemporary art curator interested in the global, transnational, and transcultural histories of modern and contemporary art between Asia, Europe, Latin America, and North America. She has been a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, Cleveland Museum of Art, and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. She has an MA in Japanese art and architecture from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and did PhD coursework in art history at Rice University.

Rubin Museum

150 W. 17th St., NYC

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.