Mia Birdsong:

Interdependence feels like gravity. It’s just like a fact.

Devendra Banhart:

Author and futurist Mia Birdsong.

Mia Birdsong:

We humans are inherently an interdependent species. We require other folks in order to get what we need.

Devendra Banhart:

Welcome to season 5 of AWAKEN, a podcast from the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art about the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it means to “wake up.”

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host. In this season, we hear from experts in the realms of art, social science, Buddhism, and more to better understand how interdependence is the foundation of every aspect of our lives.

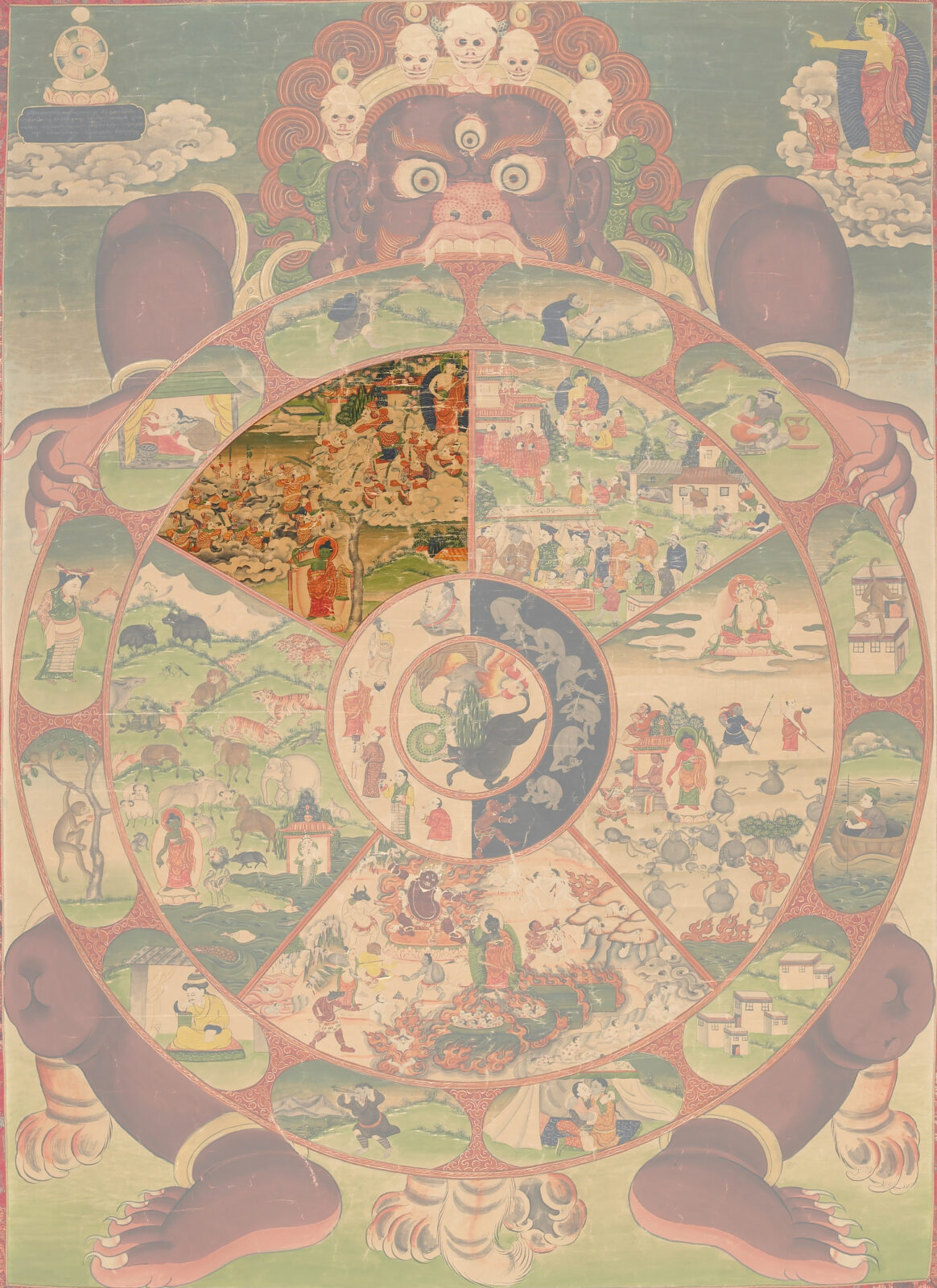

Himalayan art has long been a pathway to insights and awakening, and over the course of eight episodes we look specifically at a painting of the Wheel of Life to see what it can teach us about the interconnected nature of existence.

Throughout this journey, we’ll discover how greater awareness of our interdependence can be the wake up call that motivates us to take actions for a better world.

In this episode, we are looking at community on a personal level—the people you know directly and engage with on a regular basis.

Professor Nicholas Christakis is a social scientist and physician who conducts research in the areas of social networks and biosocial science, and directs the Human Nature Lab at Yale University.

Nicholas Christakis:

It’s a truism that we are a social animal, everybody knows that. But what’s interesting about our sociality is that we’re social, not just in the sense that we live in groups, you know, a herd of cattle or a mass of crocodiles live in groups. We don’t just live in groups. We live in networks. Evolution has shaped us to not just choose our mates, but to choose our friends, to choose the individuals with whom we associate. And all those people, in turn, are choosing their own friends. And as a result of every person choosing a different number of friends and different people to be their friends and different kinds of friends, we proceed to assemble ourselves into this very ornate, baroque, beautiful structure known as a social network.

Devendra Banhart:

Mia Birdsong describes herself as a “pathfinder and futurist who reconnects us with our forgotten wisdom and practices of our collective liberation.” Her book How We Show Up: Reclaiming Family, Friendship, and Community is a reminder of our profound interconnectedness.

Mia Birdsong:

We humans are part of a really beautiful, intricate, amazing, ancient ecosystem that is Earth, and none of the life that exists on this planet is able to survive without other life. And that’s true for everything.

When I think about humans, we not only have interdependence with trees and algae that produce oxygen and plants that produce our food but we’re also an interdependent species. When we’re born, we can’t do much of anything. We really need other humans in order to have our basic needs of food and shelter and love and safety and belonging met. And I think that’s beautiful. There’s a kind of comfort there. There’s a kind of nourishment that comes from it. That’s the nature of it.

Devendra Banhart:

Acknowledging our interdependence benefits us in many ways but one of the most important is that it reminds us we’re not alone.

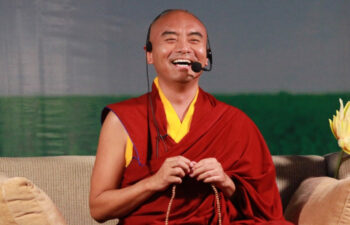

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

We are social beings, social connection with our neighbors, with the people around us. We cannot alive. We cannot survive.

Devendra Banhart:

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a renowned meditation teacher, author of several books on Buddhism, and head of the worldwide Tergar Meditation Community.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

There are so many, so much kind care, love that we are receiving every day and we are giving to others also. And most of them are unconscious level. We even not recognize it. So sometimes we cannot appreciate this love, kind, care that we are receiving and what we are giving to others.

Nicholas Christakis:

The benefits of a connected life outweigh the costs.

Devendra Banhart:

Again, Nicholas Christakis.

Nicholas Christakis:

There are costs from having friends, right? Our friends put demands on us. Having friends means we can get infections from them. Or they ask us for favors. But the net benefit to everyone exceeds the cost to everyone. And what’s amazing about this as well is that the networks that we humans make, mathematically and in other ways, are extremely similar to the networks that certain other species make, like elephants, for example, or certain whale species or certain primate species. So even though our last common ancestor with elephants was 90 million years ago, they and we independently evolved the capacity for friendship and for making social networks, which means that friendship and this interdependence that we have on each other, not just for mating, but for other non-mating activities, which means that this interdependence must be very profound indeed, and must serve an evolutionary purpose across the great arc of hundreds of thousands of years.

Mia Birdsong:

On the one hand, this is just biology. In our DNA is this interdependence because that is what human animals are, they’re an interdependent species. So part of that is just the lineage of our biology. But whether that is DNA or epigenetic memory or more of a spiritual memory or all of those things, it is there.

Devendra Banhart:

We can go really deep into thinking about all the ways interdependence has shaped us as a species across time and generations. But it’s also important, and possibly more tangible, to think of the ways interconnectedness shows up in our day-to-day lives, the seemingly mundane ways that are actually the most impactful. Mia Birdsong shares one example that is close to her heart.

Mia Birdsong:

This text thread that I have with some of my neighbors. There are eight of us on it. And it’s things like, does anybody have some potatoes? Like it’s the evening, somebody is clearly cooking something that needs potatoes. And someone asked the thread, does anybody have some potatoes? And then we’ll get a picture of potatoes being left on the fence in between two houses. Like an offering of potatoes. Or I’m gonna be late at work. Can someone let my dog out? And, and we often, if we’re asking for lemons or potatoes or soy sauce or whatever, there are children of ours who will go deliver the thing to the other house. This is a thread that has existed for years and there’s something about the kind of consistency of it, and the light touch that we have on a regular basis with these people who are, next door or across the street from us, that is weaving of the fabric of our connection.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

I mean now, there’s water in my cup.

Devendra Banhart:

Again, Mingyur Rinpoche.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

This water cannot be there without others. So Buddha said, you came to the world, you just being born. If there’s no other people taking care of you, like your parents, grandparents, society, hospital, doctors, the food, all the shops, whatever, you will die alone. So we are survive until now because of others. So the neighbor that our community, the friends, the family, all this are the, the one of the most important supporter for ourself to, I’m still alive because of their cause and condition come from them giving me. And there’s a lot of kind there, there’s a lot of love.

Love and compassion is based on interdependence. If there’s no love and compassion, special humanity, special for the social being, we are social being, social connection with our neighbors, with the people around us.

Annabella Pitkin:

The reality is that we are part of an interdependent, interconnected reality in which things affect each other, in which there’s this infinite multiplicity of causes and conditions that all are connected organically to each other.

Devendra Banhart:

Professor Annabella Pitkin teaches Buddhism and East Asian Religions at Lehigh University.

Annabella Pitkin:

And this supports important aspects of thinking about wisdom, because one of the affordances of that insight of interdependence is that it decenters the self and the ego. It’s a revelation of a kind to realize that one is not ever alone, and one is also not the center of the universe. One is part of a web, an infinite web of relationships. So that insight is the wisdom that propels an individual along the path to enlightenment.

Mia Birdsong:

The idea of a self-made person is hiding the ways in which you have benefited from others supporting you, that hidden and devalued labor is often from women, particularly women of color. And it also means that we end up with this identity that is about accumulation.

When I think about that, and I think about what it would mean to live, in a society where we were pursuing what I think about as interconnected freedom, right? Or interdependent freedom as opposed to individualistic freedom. When I think about what if that was the thing that we pursued, what would our economy look like? What would our healthcare system look like? What would our relationship to the land be like, what would our neighborhoods, like, how would they be designed? How would we spend our time? And when I think about that, I imagine what’s necessary for a society in which we all have what we need, where we’re really centering the care, right? And belonging and love of the rest of the people in our society, like that really shifts things from what we have right now. And I’m like, well, that’s the world I wanna live in so let’s do that instead.

Annabella Pitkin:

In a very real way, that wisdom that decenters, the kind of erroneously perceived egocentric self is indivisible from hand in hand with the compassion and loving kindness of relationality and ethical action.

Mia Birdsong:

It’s not that in the context of interconnected freedom, we don’t have agency and self-determination. It is that our agency and self-determination is actually supported by interconnected freedom. It is that everyone, if, if we’re all being cared for, if we’re all having our needs met, then our self-determination is unleashed. It actually means that my needs can’t be met unless your needs are met. I need everyone around me to be okay so that they’re not scrambling and spending their time and energy trying to figure out how to get what they need.

Devendra Banhart:

This season we’re focusing on a painting of the Wheel of Life in the Rubin Museum’s collection. The Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, is a foundational symbol in Buddhism and offers a visual representation and reminder of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Part of the wheel depicts the six realms of existence where it is possible to be reborn. To see the artwork in detail, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

In this episode, Annabella Pitkin looks at the god realm.

Annabella Pitkin:

We’re looking at lots and lots of clouds. There are small figures with a lot of gold on them, golden helmets, golden garments, riding on clouds. These are not creator gods. These are a kind of gods and demigods of a kind of mythological variety. And they have all the pleasures. They’re floating on clouds. And what are they doing with that extraordinary array of possibilities and resources? They’re envying each other and fighting one another. And that is so heartbreaking. The Buddhist description of the god realm has a real quality of almost tragedy to it that speaks very much to what can sometimes go wrong in our own circles and communities where rather than experience the interdependence that we actually are in with one another, where your happiness or your distress is my happiness and my distress, and where according to the Buddhist analysis, it is very much possible for you and I to both be happy if we work together for our mutual happiness.

It’s such a shame then to see the gods squandering their possibilities, and all of their resources in this toxic emotional state of envy and battling. And on the other hand, this image, this particular panel, the Wheel of Life overall, are fundamentally, realistic about the real sufferings that we create for ourselves and others, the real sufferings we experience in our day-to-day lives and within the jaws of death, as it were. But there’s also a profound optimism, a kind of can-do attitude that’s very striking. So the gods in this god realm, they are not alone. There’s a hint that the arts actually may have some kind of liberating, transformative teaching power.

We may often tend to focus on the struggles or the battles or what our differences are, but the access to the knowledge that we actually are connected and that we have far more in common than we do that divides us, access to that is always present. That wise voice, maybe that’s the voice in one’s head or one’s heart. Maybe it’s a voice in the outside world that says, what if we put the weapons down? What if we join the clouds? What if we noticed what wonderful opportunities and resources we actually have right now? And we shared them? That voice is always available.

Mia Birdsong:

One of my most clarifying experiences was when I did organizing around abolition. Organizing is a communal process. You’re in relationship with the other people you’re doing organizing with, and you’re reaching out to other humans.

What are we building that is nourishing for people, that is caring for people, that allows people to have a sense of dignity and beauty and meaning in their lives. And that dreaming, the vision that we were talking about was deeply communal. So the idea that we were building a society in which everybody was actually cared for, and that that happened in a deeply communal way, was really powerful for me.

Devendra Banhart:

According to Nicholas Christakis, our instinct to form mutually supportive relationships is in our blood and bones, it’s what we’re meant to do.

Nicholas Christakis:

These are clearly physiologic things that are happening that lie behind this human propensity to form friendships. So our interdependence, our capacity for forming these friendships is deeply written in our bodies. We have the physiologic and cognitive apparatuses that support this extraordinary phenomenon.

Mia Birdsong:

I think it’s really about recognizing that all life on this giant ecosystem that we all share is something that we’re connected to, and that that is actually worthy of celebration, we can find joy in that.

I think it starts with feeling ourselves and feeling the ways in which we are already interdependent. That’s not a thing you need to create, it’s there already. But feeling into it and where it already exists and feeling into where you have longing for connection, I think those are the things, right? Those are the ways in which your internal compass will kind of guide you.

Our job is to listen and to, to recognize that it’s there and to connect to what it feels like and to clear away whatever is locking that message and really tune into it and trust it enough to allow it to guide us.

Devendra Banhart:

Tuning in, trusting. It’s already right here, we just need to open our eyes and hearts to the profound truth of our interconnectedness.

You just heard the voices of Mia Birdsong, Nicholas Christakis, Annabella Pitkin, and Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host.

To see the artwork discussed in this episode, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

If you’re enjoying the podcast, leave us a review wherever you listen to podcasts, and tell your friends. For more stories and news from the Rubin, follow us on Instagram @rubinmuseum and sign up for our newsletter at rubinmuseum.org.

AWAKEN season 5 is an eight-part series from the Rubin.

AWAKEN is produced by the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art with Kimon Keramidas, Gracie Marotta, Christina Watson, and Sarah Zabrodski in collaboration with SOUND MADE PUBLIC, including Tania Ketenjian, Philip Wood, Alessandro Santoro, and Aaron Siegel.

Original music has been produced by Hannis Brown with additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

AWAKEN Season 5 is sponsored by The Prospect Hill Foundation and by generous contributions from the Rubin’s Board of Trustees, individual donors, and Friends of the Rubin.

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council.

Thank you for listening.

We may think interdependence is something that needs to be found, but it’s already right here, existing among the people we know and interact with on a regular basis. Our capacity to form mutually supportive relationships is a human drive deeply written in our bodies. What does it look like to seize upon and celebrate those connections?

For centuries people have turned to the image of the Wheel of Life to better understand cause and effect and the very nature of existence. The section of the Wheel depicting the god realm is the focus of this episode’s exploration of community.

This episode features author and futurist Mia Birdsong. AWAKEN season 5 is hosted by singer, songwriter, and artist Devendra Banhart. Other guests in this episode include social scientist, physician, and professor Nicholas Christakis, professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions Annabella Pitkin, and Tibetan Buddhist meditation teacher and author Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

Complete our listener survey for a chance to win two free tickets to the Rubin’s Mindfulness Meditation program in person or online.

Wheel of Life, attributed to Lhadripa Rinzing Chungyalpa (b.1912, Sikkim–d.1977); Sikkim; c. 1930; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2004.21.1

One of the most important teaching tools in Tibetan Buddhism is the Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, which demonstrates the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. The scenes within the wheel portray the laws of karmic cause and effect, illustrating how a person’s actions bring about positive or negative outcomes in their current and future lives.

This episode focuses on the god realm, which comprises gods seemingly living the good life, eating ambrosia, enjoying eternal youth, and having every wish fulfilled. But this carefree existence is also extremely dangerous to the spirit—the gods have little incentive to help others or enlighten themselves because they live in ultimate comfort and luxury. The gods are isolated from real life and can struggle to understand the suffering of others. So when the gods die they risk a truly terrible series of rebirths as karma for all of the time they wasted. The demigods, shown attacking the gods, are striving to obtain what the gods have. This realm serves as a reminder to not grow complacent or remain ignorant of the suffering of others, and instead work toward changing the world for the better.

Devendra Banhart is an internationally renowned musician considered a pioneer of the “freak folk” and “New Weird America” movements. Banhart has toured, performed, and collaborated with Vashti Bunyan, Yoko Ono, Os Mutantes, the Swans, ANOHNI, Caetano Veloso, and Beck, among others. His musical work exists symbiotically alongside his pursuits in the other fine arts including painting, poetry, and drawing. The Venezuelan American has released 11 albums. His drawings and paintings have appeared in galleries all over the world, including the Art Basel Contemporary Art Fair in Miami; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels; Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; Nicodim Gallery; and Serralves.

Mia Birdsong is a pathfinder, futurist, founding executive director of Next River, and author of How We Show Up: Reclaiming Family, Friendship, and Community. Her work reconnects us with our forgotten wisdom and practices of our collective liberation. She brings her contagious curiosity to her writing, interviews, and public conversations. Mia champions the inherent worthiness of people in both her podcast series More Than Enough and her TED Talk on The Story We Tell About Poverty Isn’t True. Her most recent work, Freedom’s Revival: Research from the Headwaters of Liberation, charts the interconnected nature of “freedom.”

Nicholas A. Christakis, MD, PhD, MPH, is the Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science at Yale University. His work is in the fields of network science and biosocial science. He directs the Human Nature Lab and is the co-director of the Yale Institute for Network Science. He was elected to the National Academy of Medicine in 2006; the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2010; the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2017; and the National Academy of Sciences in 2024.

Annabella Pitkin is associate professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University. Her research focuses on Tibetan Buddhist modernity, Buddhist ideals of renunciation, miracle narratives, and Buddhist biographies. She received her BA from Harvard University and PhD in religion from Columbia University. She is the author of Renunciation and Longing: The Life of a Twentieth-Century Himalayan Buddhist Saint, which explores themes of non-attachment and teacher-student relationship in the life of Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen. More →

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a recognized tulku of the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, a teacher, spiritual leader, and bestselling author. He possesses the rare ability to present the ancient wisdom of Tibet in a fresh, engaging manner. His profound yet accessible teachings and playful sense of humor have endeared him to students around the world. Rinpoche’s teachings weave together his own personal experiences with modern scientific research in relation to the practice of meditation. He has authored several books including two bestsellers: The Joy of Living: Unlocking the Secret and Science of Happiness, which has been translated into over 20 languages, and In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying. His recent TED Talk is titled “How to Tap into Your Awareness—and Why Meditation Is Easier Than You Think.” Rinpoche teaches extensively around the world and oversees dharma centers, including three monasteries in Nepal, India, and Tibet, and the Tergar Institute in Kathmandu; Tergar meditation communities on six continents; numerous schools in Nepal; and social engagement projects related to health, hunger, hygiene, the environment, and women’s empowerment issues in the Himalayas.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.