Ideas about gender vary among cultures. Himalayan peoples have historically depicted their deities, ideal beings, as neither male nor female. Indian expressions represented gods as fleshy and lacking muscle tone, distinctly different from the strapping depictions of gods in Western art. Art historians have often interpreted these fleshy bodies as being made purposefully androgynous to suggest an ultimate state of enlightenment that is beyond the binaries of gender. The fleshy body also suggests a body filled with prana, or life force, that is often equated to the breath. Several objects in the Rubin Museum’s collection illustrate these ideas.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara; Nepal; 13th - 14th century; Gilt copper alloy with semiprecious stone inlay; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2005.16.8

In both Tibet and Nepal, the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara has always been presented as male. When Buddhism spread to China, the name Avalokiteshvara was translated from its Sanskrit origins into the Chinese name, Guanyin. Around the 12th century in China, Guanyin began to be presented as a woman instead of a man. Some have suggested this shift from male to female relates to passages from the Lotus Sutra, which describes Avalokiteshvara’s ability to take any form in order to help beings out of his/her infinite compassion. Eventually, Guanyin became known as a patron of mothers and sailors in China, with most temples depicting the deity as a woman and some still presenting him/her as a man.

Shiva and Parvati; Nepal; 13th century; Metal; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2005.16.12

For many Hindus, Shiva and Parvati represent the ultimate divine couple. The sculpture above depicts Shiva sitting with Parvati, the two appearing to melt into one another. One particular form of Shiva and Parvati is known as Ardhanarishvara (lord that is half woman), in which both traditional genders are merged to form a new being that is neither and both.

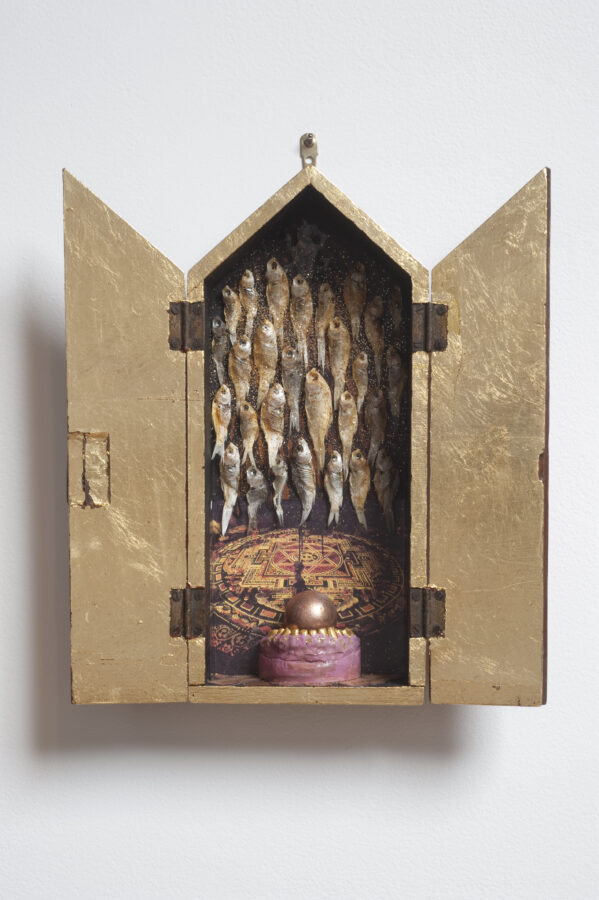

A sculpture of Shiva and Parvati was on display in the 2016 exhibition Genesis P-Orridge: Try to Altar Everything. Contemporary artist Genesis Breyer P-Orridge and h/er late partner Lady Jaye modeled themselves after the unity of the divine couple by seeking an identity beyond a gender binary. During the process of the Pandrogyne Project, Genesis and Lady Jaye attempted to transcend gender by becoming as similar as possible in looks and behavior, undergoing numerous plastic surgeries to create two halves of one being.

Next to the sculpture of Shiva and Parvati was a carpet made in Nepal depicting Genesis and Lady Jaye in the form of Ardhanarishvara, linking their inspiration to this ancient ideal, and much of the art in the exhibition also addressed themes related to pandrogeny. These examples offer a glimpse at the approaches to gender and identity in traditional Himalayan cultures and how they differ from popular approaches in Western culture.

Rubin Museum

150 W. 17th St., NYC

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.