Vajrabhairava Mandala; Ngor Ewam Choden Monastery, Tsang Province, Central Tibet; ca. 1515-1535; Pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2005.16.40

Vajrabhairava Mandala; Ngor Ewam Choden Monastery, Tsang Province, Central Tibet; ca. 1515-1535; Pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2005.16.40

Many of us are trying to find little moments of zen in our day-to-day lives. Some look to the Rubin Museum to do just that, whether it’s by joining a Mindfulness Meditation session or by quieting the mind in the Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room. But can you really describe the Rubin and its collection as “zen”? That depends on what you mean. The concept has become so popular in American culture that its meaning has changed. Here’s why you might think again before calling the Rubin “zen.”

Above is an 18th-century painting of the Buddha holding a flower. According to legend, a large gathering of monks came to Vulture Peak to hear his teachings. When he sat in front of the monks, instead of speaking all the Buddha did was hold a single flower. All the monks were confused, except a monk, Mahakasyapa, who understood the unspeakable truth of the Buddha’s gesture. From this teaching stemmed the Zen tradition. Buddha Shakyamuni; Tsang Province, Central Tibet; 18th century; Pigment on cloth; Rubin Museum of Art; Rubin Museum of Art, Gift of Shelley and Donald Rubin; C2006.66.128

For many people, the term “zen” is synonymous with Buddhism. However, Zen is actually only one of many different Buddhist traditions. The specific sect of Zen Buddhism was the first to take root in the West, which helps explain why the connection between the idea of Zen and the religion of Buddhism in America is so strong.

The first formal introduction of Zen to America was likely during the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, where Zen teacher Shaku Soen spoke at the World Parliament of Religions. By the 1950s and 1960s, several Zen Buddhist masters began to immigrate to the United States, establishing major Zen centers in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Just a few years later, members of the counterculture movement of the 1960s like Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, and Jack Kerouac would study at these centers, and later incorporate Zen teachings and terminology into their writing. These texts helped Zen expand into American culture and thought.

“Zen” is a common word used by many to describe anything or anyone who seems calm and grounded, but what does the word actually mean? Though “zen” is a Japanese word, the Buddhist tradition called Zen actually originated in China under the name chan during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE). The term “chan” itself is the Chinese version of the Sanskrit word dhyana which is often translated into “meditation.”

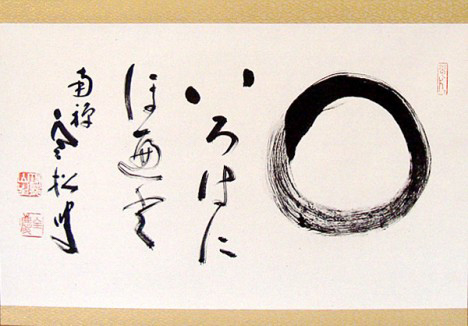

Example of Zen style painting.

The Rubin’s collection features art from the Himalayan region, which traditionally practices a different type of Buddhism known as Vajrayana, Tantric, or Esoteric Buddhism. According to the legend, during the eighth century the great Tibetan emperor Trisong Detsen held debates between Chinese Buddhists (chan or zen) and Indian Buddhists (Vajrayana) to decide which type of Buddhism the empire was going to adopt as a state religion. Ultimately, the Indian Buddhists won, resulting in Vajrayana influences seen in much of Himalayan art henceforth.

A sculpture of the tantric deity Chakrasamvara in union with his consort Vajrayogini. Zen temples would not depict beings like this in sexual embrace. Chakrasamvara in Union with Consort Vajravarahi; Central Tibet; 14th century; Gilt copper alloy with pigments and turquoise inlay; Rubin Museum of Art; Rubin Museum of Art; C2005.16.16

The two traditions differ when it comes to how enlightenment is achieved. Zen strongly emphasizes meditation and what’s called “spontaneous” enlightenment. By simply meditating as much as possible, a person creates the opportunity for enlightenment to arise within them. Vajrayana, on the other hand, teaches a path of “gradual” enlightenment, providing a prescribed system with the use of many rituals and objects, which is often surprising to many Westerners when comparing Vajrayana to Zen’s minimalist aesthetic.

The Vajra is used to dictate many rituals in Vajrayana Buddhism and is something that would not be found in the Zen tradition. Vajra Scepter; Tibet; 16th century; Metalwork; Rubin Museum of Art; Rubin Museum of Art; C2004.31.3

Prayer beads with images of Bodhidharma’s face carved in them. Bodhidharma supposedly brought the tradition of Zen, or rather Chan, to China during fifth and sixth centuries. Prayer beads made of seeds, likely bladdernut, with image of Bodhidharma carved on each bead; Korea; Early 20th century; Bladderbut seeds (likely) and thread cord; Rubin Museum of Art; Rubin Museum of Art, Gift of Anne Breckenridge Dorsey; C2014.6.13

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.