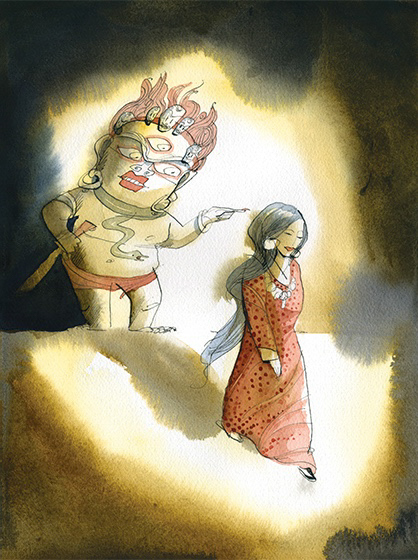

Illustration by Marcellus Hall

Illustration by Marcellus Hall

The idea of resurrection comes up again and again, across time and cultures. It is one of the most persistent ideas to capture our imaginations, popping up in storytelling, traditional opera, and popular television. I am not referring to the risen corpses of the zombie-inspired television series The Walking Dead or other media. I mean fully conscious, fully aware people who come back from the dead as if they did not die.

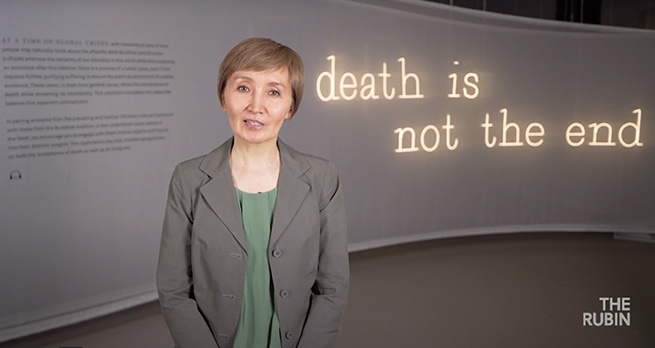

While researching notions of the afterlife for the cross-cultural exhibition Death Is Not the End, I have encountered surprising parallels between tales from Tibetan Buddhist culture and several contemporary television series. The returned always seem to reappear with sights to describe and lessons to impart.

Tibetan Buddhist culture features popular narratives and written accounts about people who came back to life after dying. Tibetans call them delok, meaning returned from the dead. (The concept of risen or animated corpses is different and has its own separate term.) The returned-to-life people are usually quite ordinary, but they have extraordinary stories to tell. They describe what they saw and experienced after death. Each story is usually narrated in the first person, making it highly personal and emotionally charged.

One such popular story is about Nangsa Wobum, a woman who may have lived in the late eleventh or twelfth century in south-central Tibet. She wished to devote herself to a spiritual life, but was forced into marriage and died from mistreatment by family.

This detail of the core of the Wheel of Life shows the ultimate conditions of suffering and the afflicting emotions that cause it, symbolized by the pig (ignorance), snake (hatred), and rooster (attachment). The surrounding circle depicts virtuous and non-virtuous actions represented by the figures in upward and downward postures. This part of the Wheel also refers to beings who are in the intermediate state, or bardo, between death and rebirth. Detail of Wheel of Life; Tibet; early 20th century; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Art; C2004.21.1 (HAR 65356).

After Nangsa dies she is confused, not realizing that she has passed away until she sees her surroundings. Along with the other dead people, she is taken in front of the Lord of Death, who weighs her positive and negative karma, counting the good deeds as white pebbles and negative deeds as black pebbles. He proclaims that her karma to live as the woman Nangsa Wobum is not finished and she has to continue her human existence. To the amazement and awe of everyone in her village, she comes back to life and shares her story, finally embarking on a religious life as a nun. She describes her experience in the afterlife, seeing the beings who commit negative karma suffering in hell and witnessing the salvation of others thanks to their good karma or divine intervention. Through her work she affects the lives of those who wronged her and caused her death, thus helping to alter their karma and escape the suffering that would have awaited them in the afterlife had they not changed their ways. By returning from death she teaches the living how to live. Itinerant storytellers recounted the tale of Nangsa, and her story became a popular Tibetan opera. Until the twentieth century public storytelling and opera performances were among the most popular forms of entertainment in pre-modern and modern Tibet.

There is a curious parallel here with television shows about the returned in our own popular culture.

The French television series The Returned (Les Revenants, 2012–2015), based on the horror film They Came Back (2004), is about people who died long ago but suddenly reappear alive, unaged, and unaware of their deaths. Their reemergence complicates the lives of everyone involved, as the returned, their families, and others must figure out how to solve the ensuing problems. An American version titled The Returned (2015) explores a similar premise.

The Australian show Glitch (2018–2019) is the most recent show on this subject. In Glitch the returned literally dig themselves out of their graves, but they are also unaware that they have died. Their memories gradually return through interactions with people in their new reality. People and plots are intertwined, hinting at or evoking karmic connections in the characters’ relationships that need to be resolved and drive the show’s narrative.

Interestingly, Glitch also contains references to notions from Chinese Buddhist culture. A nineteenth-century Chinese man who came to Australia for work is among the newly returned, and he grapples with the strangeness of his new surroundings. He mistakenly thinks he has been reborn as a hungry ghost (preta in Sanskrit), a being who wanders in a ghostly existence of suffering.

Like the nineteenth-century Chinese man, some of the returned are not from the time in which they have reappeared, adding to the complexity of their stories, their identities, and the consequences of their return. The main underlying fabric of the show’s imagined reality involves karmic connections and the possibility of resolving tangled relationships while questioning what it means to be human.

From classic stories of Tibetan delok to contemporary television, the idea of the dead returning to life spans centuries and continents. In all these examples, the returned discover their individual purpose and strive to complete the lives that death interrupted. Some remember the terrible, horrifying sights of what lies beyond and threatens to spill over into this world. They pursue different paths inspired by their experiences, but many eventually change themselves and the people around them.

The idea of a second chance is a well-known concept, often accepted and favored in Western culture. In Buddhist culture it is a bit more complex, as it is presented in the context of karma and rebirth rather than redemption. Regardless of origin, stories of the returned are tantalizing and worthy of serious contemplation, for all of us wonder what lies beyond and what we would do if given the chance to know.

Representations of the afterlife from Buddhist and Christian traditions were featured in the exhibition Death Is Not the End at the Rubin Museum from March 17, 2023, to January 14, 2024.

Elena Pakhoutova is senior curator, Himalayan art, at the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art and holds a PhD in Asian art history from the University of Virginia. She has curated several exhibitions at the Rubin, including Death Is Not the End (2023), The Power of Intention: Reinventing the (Prayer) Wheel (2019), and The Second Buddha: Master of Time (2018). More →

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.