Art has always been a great inspiration for poets, themselves artists, and an invaluable resource for elevating the consciousness of viewers in general, says poet Joe Pan, who is the managing editor and publisher of Brooklyn Arts Press. “It’s interesting to see questions being posed, articulated, and wrestled with in mostly non-verbal, even ineffable, ways.”

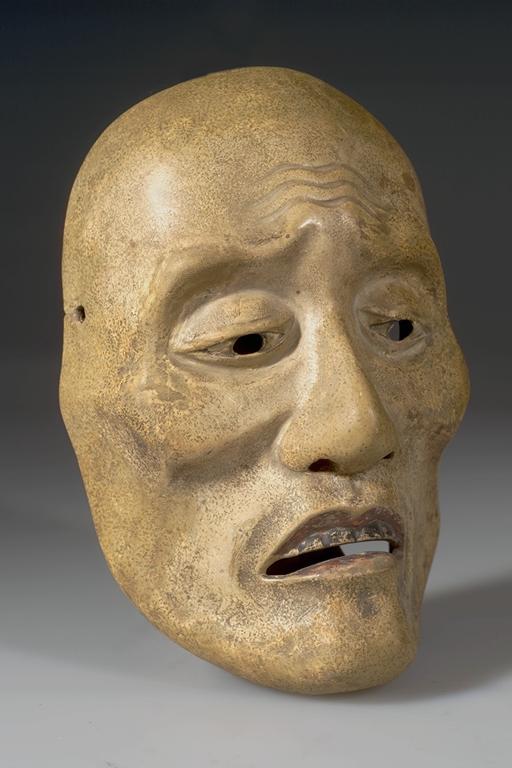

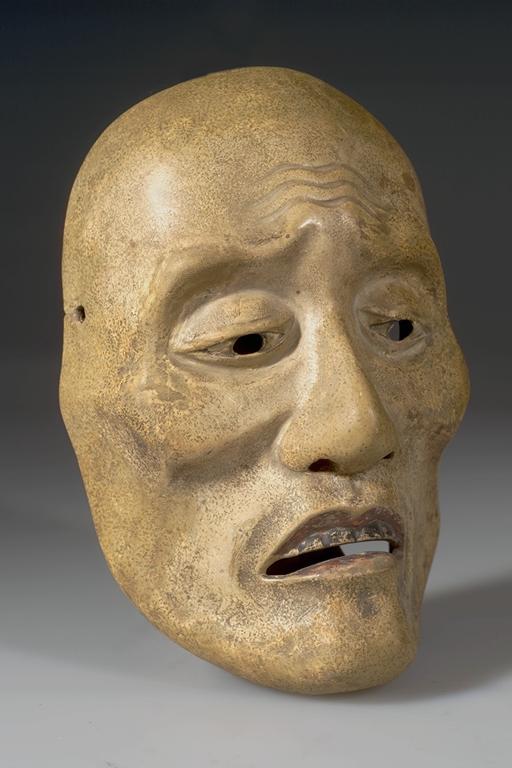

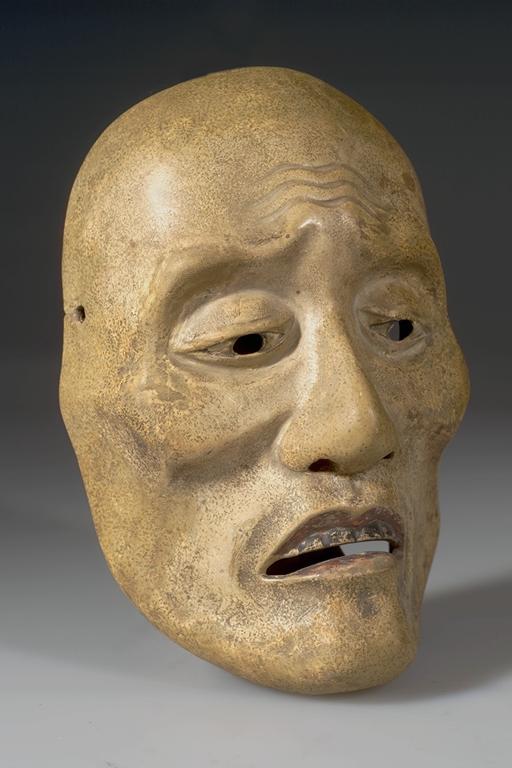

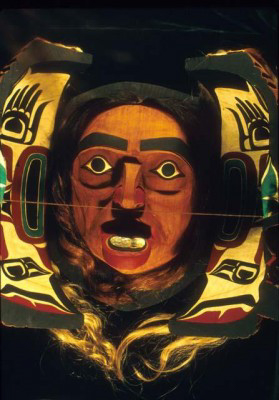

In 2015 the Rubin joined forces with the Poetry Society of America to create a collaborative audio tour of the exhibition Becoming Another: The Power of Masks. Each poet involved in the project chose a specific mask from the exhibition and then created an original poem, which they read in front of a live audience at the Museum.

This collaboration is just one example of how art and poetry can complement each other. In this Q&A, Pan gives his thoughts on poetry’s long-standing interaction with visual art, talks about the difference between “word salad” and poetry, and reminds us all to “stay curious.”

Joe Pan

As far as getting poets into a museum, all you have to do is stock it with art. We’re a curious bunch. It’s always exciting to see how cultural themes are handled differently or similarly by writers, utilizing language, and artists, using material-based visual media. The various tensions that arise in each are fascinating to me and in the past have led me to attempt something in writing I first saw achieved in visual art.

Well I find poems often choose their own subjects, mysteriously, through word juxtaposition, music, play, confabulation, whatever is rolling around in one’s mind from the day’s discussions, news, personal crises, Facebook feeds. Writing with a specific subject in mind forces the poet to contend with a reader’s expectations of that subject, which the poet can either play into or subvert, but she has to be careful not to lose that certain intellectual dynamism that attends any investigation of the unknown. One remedy is to contemplate what about that subject is unknown to you.

Overall, though, I think it’s a bit harder to start off a poem with a subject in mind, given that subjects carry historical baggage and are never themselves motionless, culturally or politically. I’d offer that poems are rarely about one subject, and that there are many great instances of poems beginning one place and ending another, where the poet allows both the subject and its malleable container, the poem, to find its own way, providing more questions than answers, taking what it needs and moving on. It’s important to allow for language to accumulate in such a way that new subjects can introduce themselves and are allowed to thrive, carrying the tension. Part of a poet’s job is to consistently renew the joy of being surprised.

Oh let’s see. So many. Spatial awareness and spatial play seems more of a visual art concern, though many poets prove this otherwise and are sometimes mocked for their attempts. I enjoy seeing the page as a performative space, generously utilized. Poets deal with language at its core, at the points of its undoing and misunderstanding, the nitty gritty, playing along the fault-lines, and have fun in the rebuilding of language for literary purposes. Visual art can ignore our language completely, if it so chooses, and build its own or have viewers accept a piece as being non-referential, which is enviable, this ability to evoke and express indeterminately, as it’s much more difficult to bypass the freight of words meaning things in poetry. Poets who attempt to focus on the musicality of language or play with font or the shape of single characters, for instance, are called visual artists not poets, symphonic , or creators of word-salad. I for one like variety and wish there was more crossover or hybrid work out there. But it is hard to get past words as symbols, performing referentially, with the power dynamics inherent in that process.

In terms of similarities in making work, it may sound trite but both are created by humans testing their ideas and limitations and provoke within their viewers/readers not dissimilar responses. I find process to be extremely personal. It’s the way one inhabits habit. Creation seems to be the simple act of following an urge, and utilizing whatever tools one finds at one’s disposal, with the history of your art always at least unconsciously present. That’s not a sexy definition, but it feels right.

So many. How are we defining art here? All poems are inspired by other poems; that is, the poet recognizes she is participating in a specific contemplative mode of play with language each time she sits down to write and is inspired to participate in that history, in that process. Otherwise she’d take her thoughts elsewhere, perhaps into visual art. There are thousands of books on ekphrasis,, but if pressed to name something I was personally moved by, I’d flip the subjects around and lead readers to search out In Memory of My Feelings by Frank O’Hara, published by MoMA in the 1960s after the author’s untimely death, recently rereleased, and filled with his poems accompanied by works from his many friends in the visual arts world, including de Kooning, Johns, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, Krasner, Guston, Rivers, Kanemitsu, Marisol, Motherwell, and Brainard. All the contributed drawings were inspired by the friendship and poetry of this person they loved. It’s one of the most loving books I’ve ever held.

Read. Read more. Google. Search out what troubles you or what you don’t understand. Build a house out of your not knowing, and live in it a while. Don’t let difficulty dissuade you from practicing your curiosity, because curiosity is a practice, which can dull if unexercised. If a work provokes a reaction in you, it’s worth the investigation if only to discover the investigating was more worthwhile than the thing sought after.

Transformation Mask; Tsungani Fearon Smith, Jr. (Cherokee, b. 1948); 1979; wood, horsehair, abalone, paint; Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University Bequest of William R. Wright, 1995

Masks speak to the human impulse to transform one’s identity. Do you see this idea reflected in poetry? How so? Why do you think “becoming another” is such a universal part of human nature?

I’m wary of attributing anything to universality, though I wouldn’t deny shared instances or responses, and I do believe we share enough as individuals to make understanding each other possible. This is the main reason for literature’s existence, to bridge gaps by showing us ourselves in other forms, as other people.

In terms of someone wanting to become “another,” the impulse to do so, there are radical and practical social, economic, spiritual, and political reasons for wanting to identify one’s self with someone unlike one’s self. Each is potent territory for discussion, even heated discussion, as we’ve seen in the poetry community, with a white middle-aged man writing under an assumed Asian woman’s name, which he stated made it easier for his poems to be published (which is BS). It may prey upon those editors doing the good work of making necessary space for historically neglected or underrepresented voices, but one need only check with the local bookstore to see a very real bias at work.

But beyond these infamous instances of masking one’s identity or taking on masks lie varieties of cultural histories that include the wearing of masks for ritualistic and transformative purposes, which, it seems to me, affirms the very idea of community, with its mores, art, memory, and obligations. I would also note the use of masks to anonymize in order to rebel against the community, though the argument could be made that this, too, is in service of the betterment of the community.

The idea of transformation itself is a complicated issue. Becoming is quite different than believing one has become. But for the purposes of speaking about transformation in poetry, one can be transformed by poetry, yes. One can be altered and shaped by the experience of reading poems. I’ve been transformed by poetry, by the reading of it, by the exercise of writing it. For instance in how I now regard language, as a fickle, fluid device for building up relationships between things. Also, instead of language being something I talk through, in poetry it becomes something that begins to talk to itself. To extend this to prose writers or poets writing persona poems, to “embody” a character is a necessary act of writing and takes a great deal of investigation and commitment to pull off in the minds of readers.

But I never confuse the act of character building with “becoming another.” Understanding in service of representing the impulses, fears, and desires of another human being isn’t an act of becoming, it’s an act of understanding and ultimately compassion. It’s an attempt to bridge divides, though everything is still being flushed through your own biased brain. But the more one reads about people unlike oneself, or visits museums or galleries to view work operating outside their usual purview or scope, the more one understands the world, becoming perhaps more compassionate, which is a large part of what makes literature and art so important.

Joe Pan is the author of two collections of poetry, Autobiomythography & Gallery (BAP) and Hiccups (Augury Books). He is the publisher and managing editor of Brooklyn Arts Press, serves as the poetry editor for the arts magazine Hyperallergic and small press editor for Boog City, and is the founder of the services-oriented activist group Brooklyn Artists Helping. His piece “Ode to the MQ-9 Reaper,” a hybrid work about drones, was excerpted and praised in the New York Times. In 2015 Joe participated in the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s Process Space artist residency program on Governors Island. Joe attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, grew up along the Space Coast of Florida, and now lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Rubin Museum

150 W. 17th St., NYC

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.