Elena Pakhoutova

Senior Curator, Himalayan Art

Rubin Museum of Art

Buddhist culture is highly symbolic and employs images to convey deep meanings related to its core concepts, goals, and practices. The most recognizable images are those of the Buddha, various deities, and portraits that represent ideals, stories, and meanings formalized in typical forms, or iconography.

The exhibition introduces these typical forms using drawings (graphics), thematic text panels and art objects which serve as entry points to the fundamental ideas of Buddhist philosophy, religious practice, and their cultural expressions.

The Looking Guide provides a reference for these iconographic forms and their essential meanings.

Critical Questions Permalink

- What is the Buddhist ideal?

- How are Buddhist ideas visually conveyed?

- How do the images help in achieving Buddhist ideals?

Exhibition Permalink

There are many relevant examples of Visual Symbols of Buddhist Art in the Exhibition’s section Symbols and Meanings.

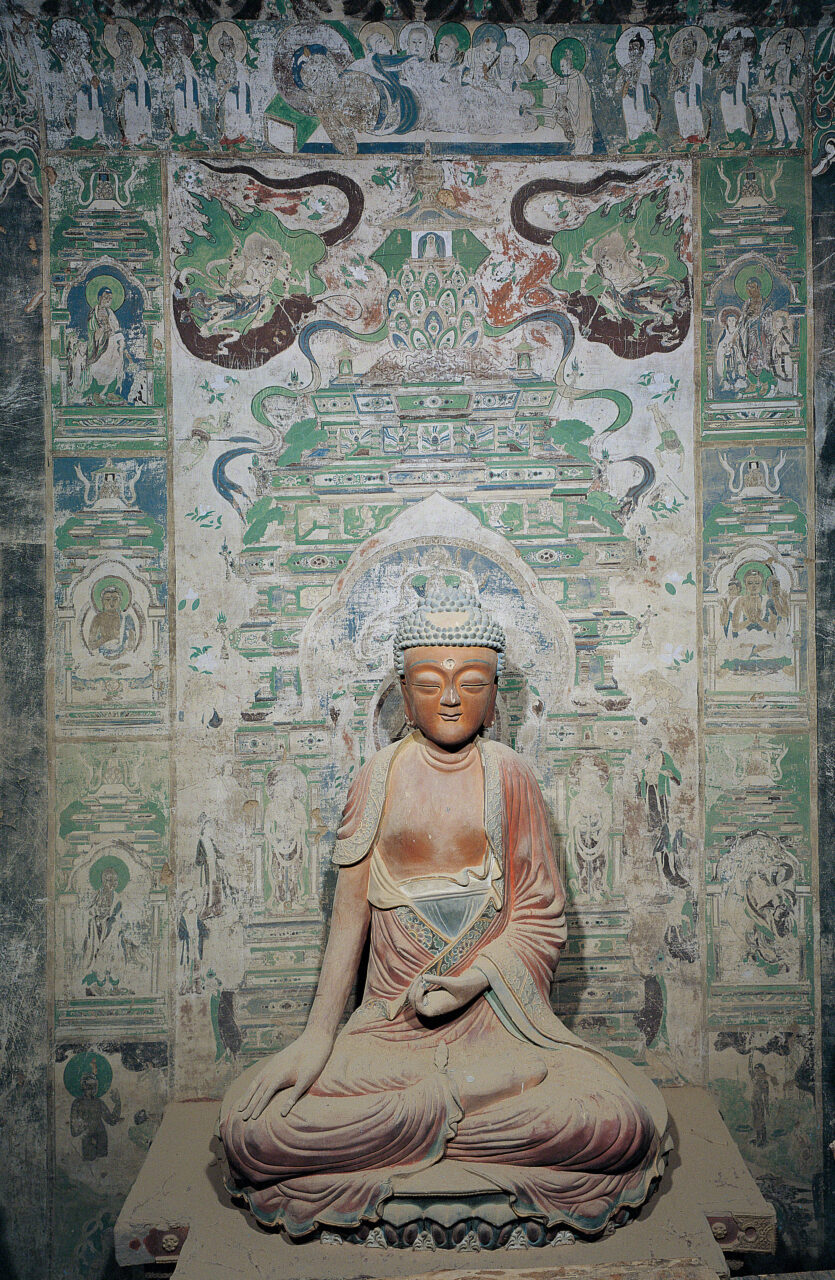

Buddha

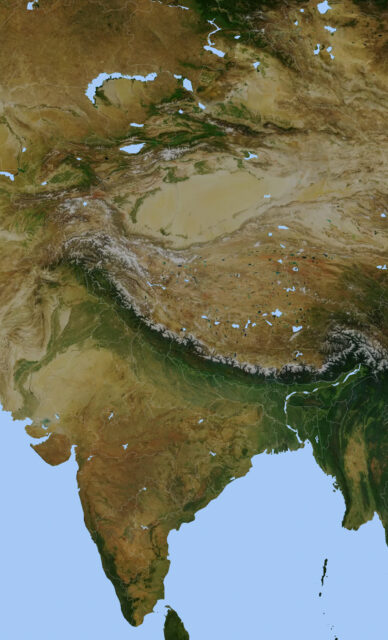

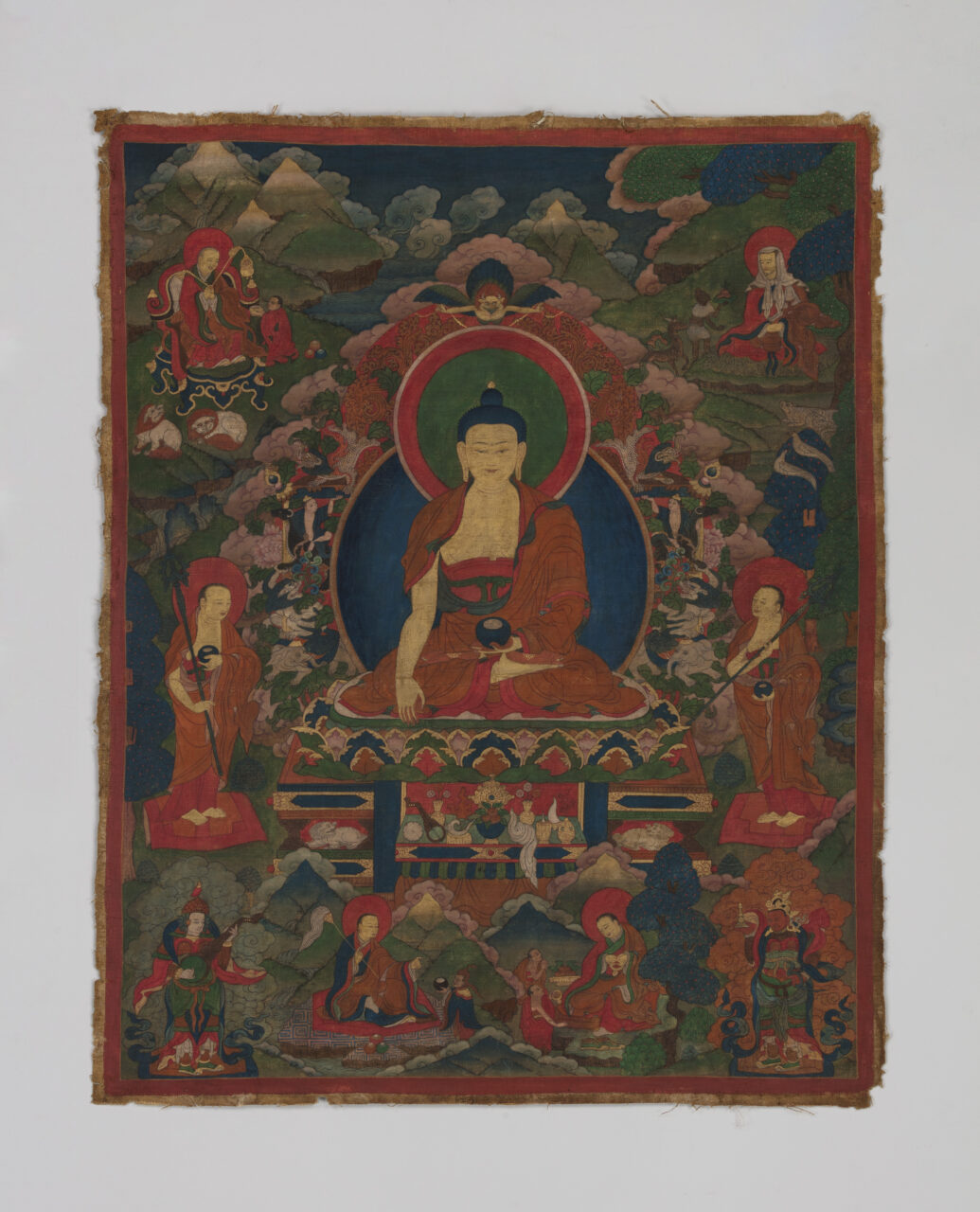

The Buddha, meaning awakened person, referred first to Shakyamuni, who lived and taught sometime between the sixth and fourth century bce in northcentral India. His teachings became the foundation of Buddhism. By understanding the true nature of reality, Shakyamuni became awakened, free from the cycle of suffering that is birth, death, and rebirth. Buddhist philosophy and practices later expanded the idea of awakening to include buddhas of the past and the future, as well as tantric buddhas who can manifest in various forms.

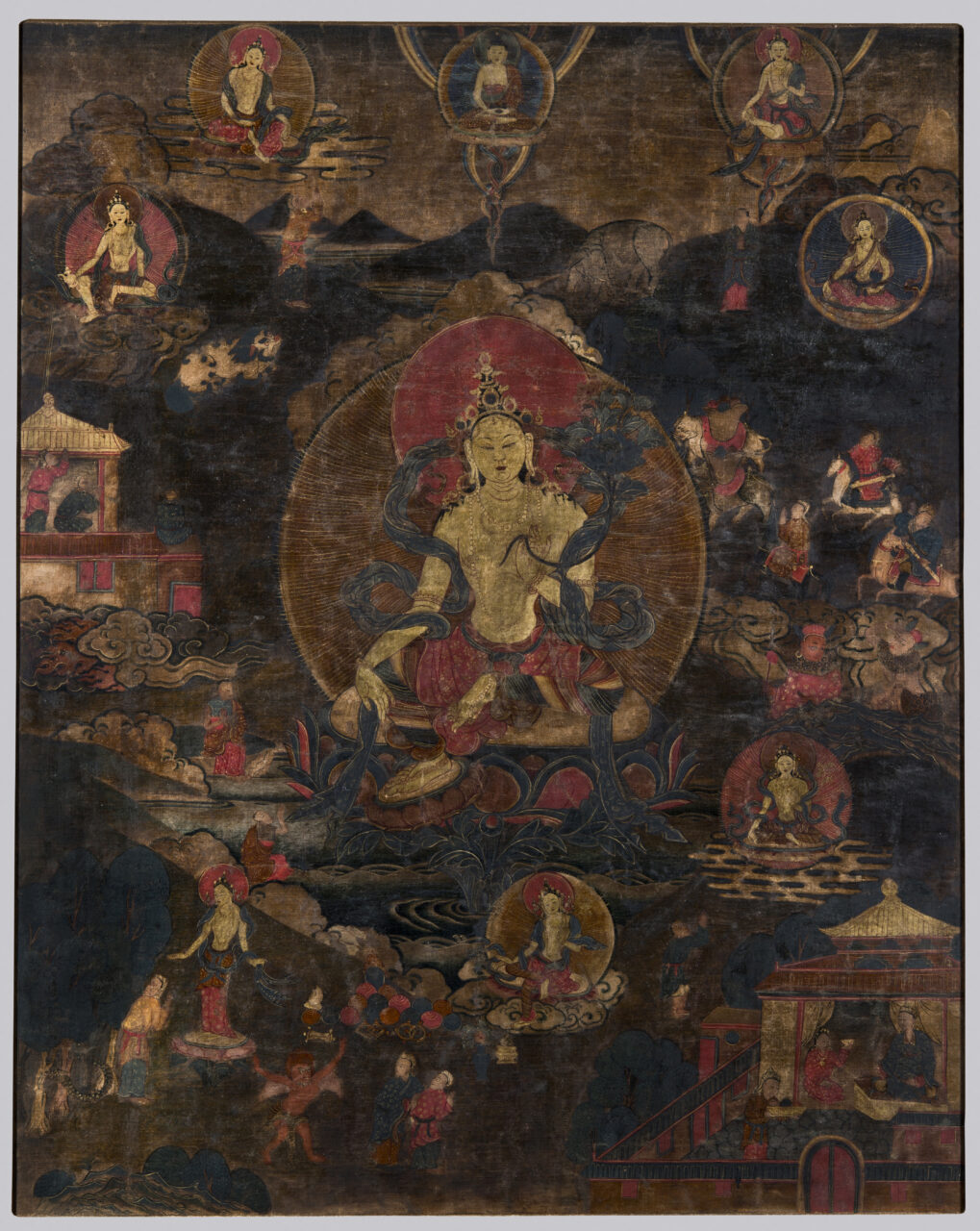

Bodhisattvas

Bodhisattvas are beings who aspire to become awakened like the Buddha and are dedicated to helping others achieve this too.They are portrayed adorned with crowns, jeweled ornaments, and garments of ancient Indian royalty. The greatest of the bodhisattvas are near enlightenment and are regarded as deities with abilities practically equal to those of buddhas. They can be identified by distinctive attributes that symbolize their particular qualities, such as the book and sword—representations of wisdom.

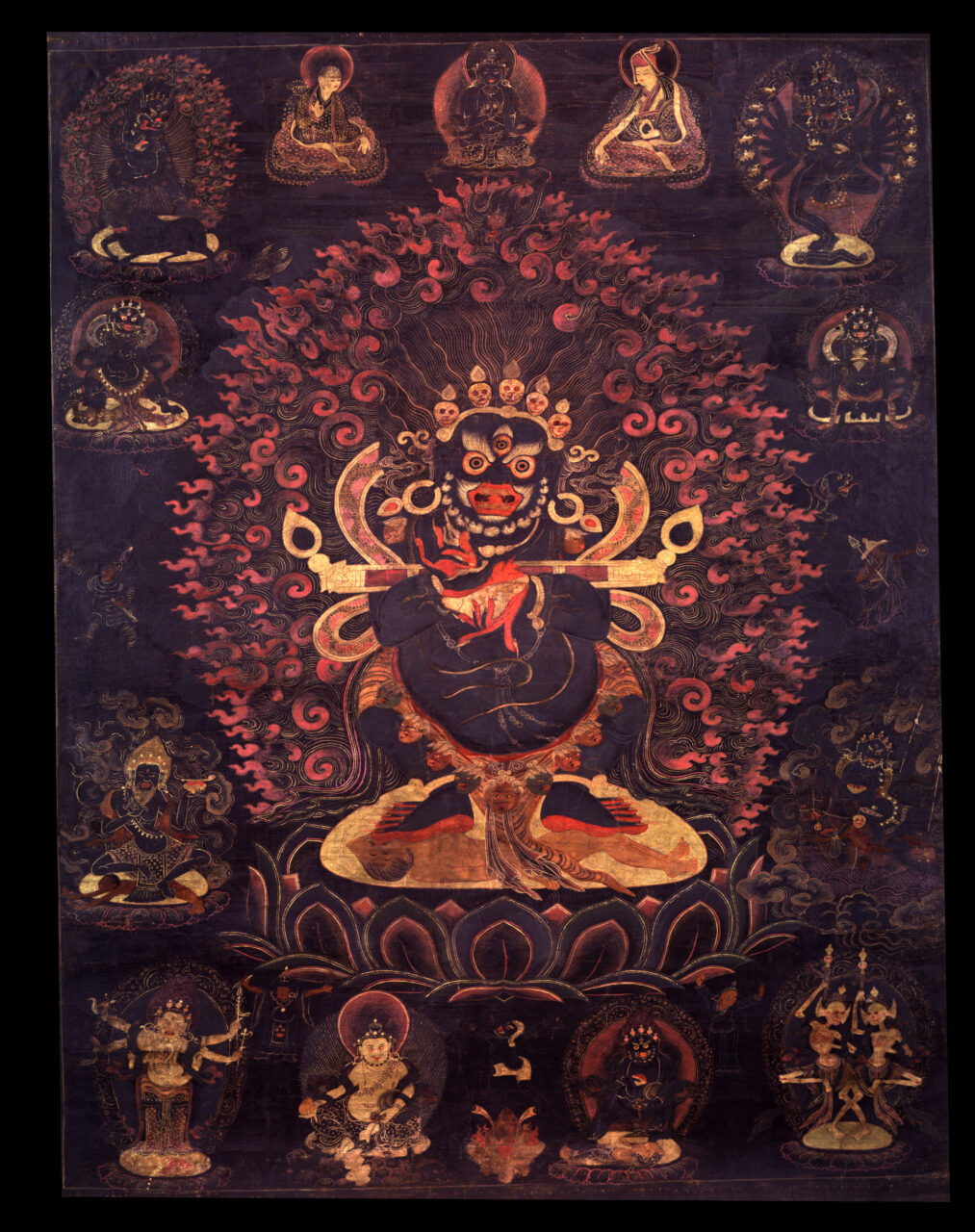

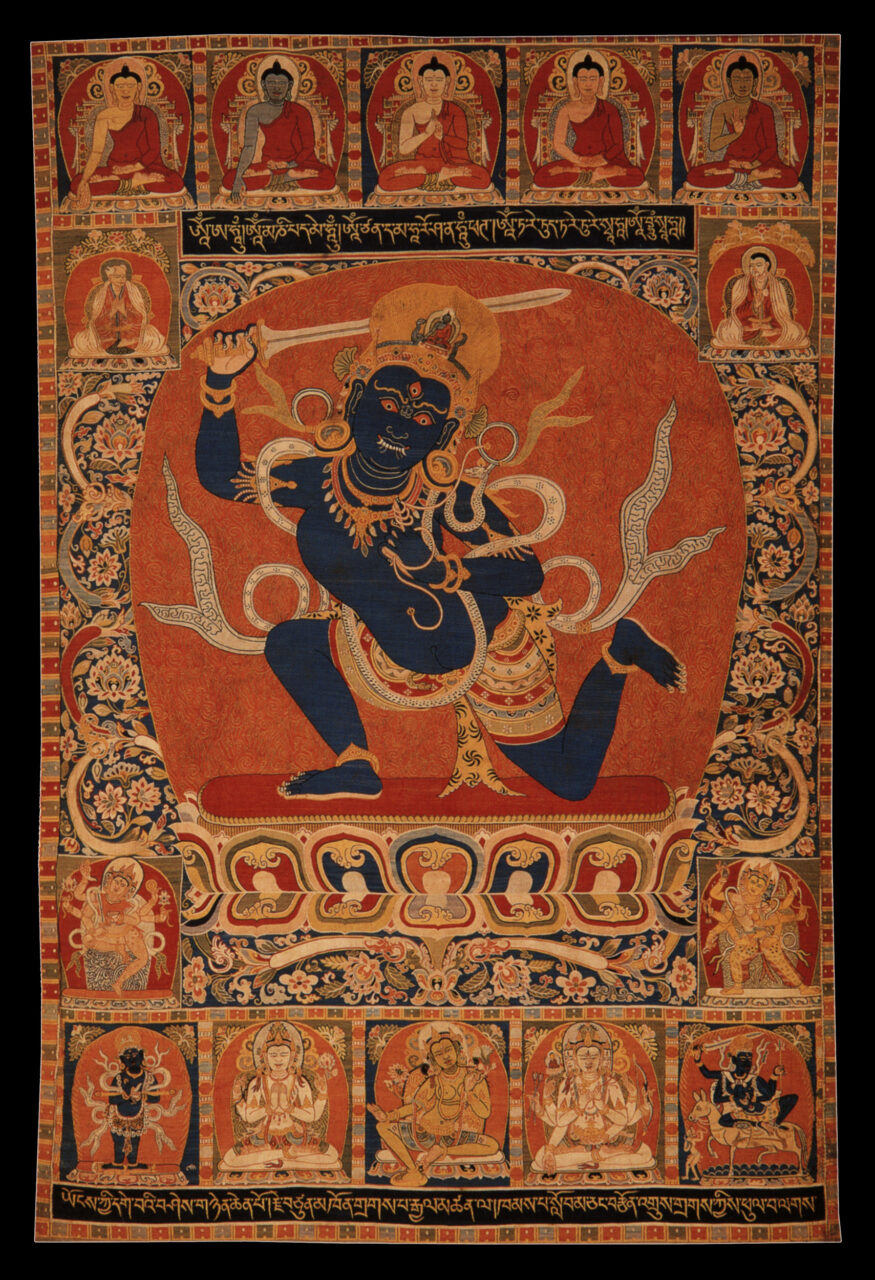

Tantric Deities

Tantric deities are the focus of esoteric religious practices (tantras) that aim to swiftly and radically transform a practitioner’s conventional understanding of reality. These secret practices require an initiation and direct instruction.

Female Deities

Bodhisattvas and tantric deities can be depicted in male or female form. In the Tibetan tradition female tantric deities are identifiable by their feminine figure, smaller size, and more oval-shaped face.

Wrathful Deities

In Tantric Buddhist traditions there are two kinds of deities that appear as wrathful, with flaming hair, bulging eyes, open mouths showing fangs, and garlands of severed heads.

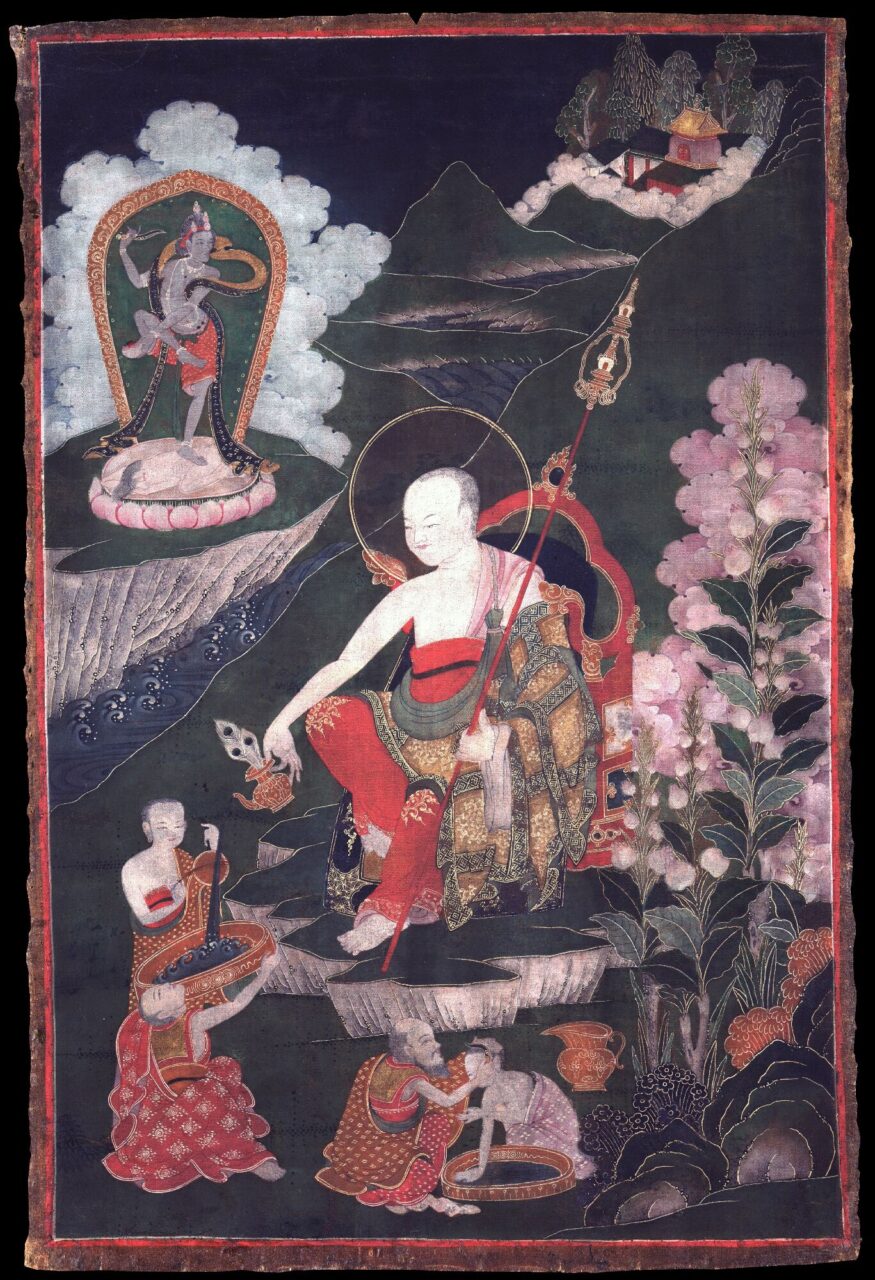

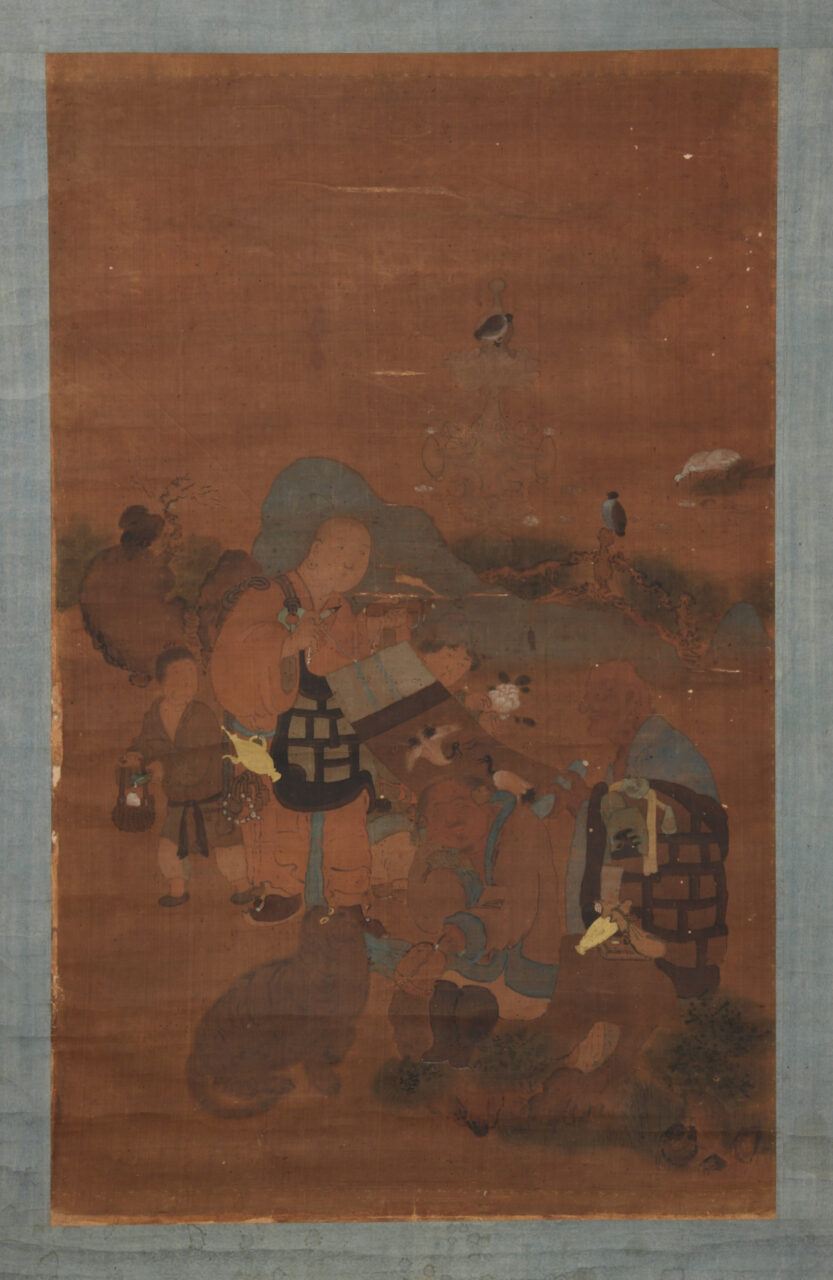

Humans

Legendary and historical humans, including Buddha’s original disciples, teachers and accomplished masters, are a popular subject of Himalayan art.

Object Essays Permalink

Several essays in the book delve more deeply into specific art examples representing these subjects.

Buddha and Bodhisattvas

Female, Tantric, and Wrathful Deities

Further Project Himalayan Art Resources Permalink

Other Object Essays Related to Buddhas

Other Object Essays Related to Wrathful Deities

Other Object Essays Related to Teachers

Other Object Essays Related to Mahasiddhas

Media Resources Permalink

The Rubin Museum of Art, "The All-Knowing Buddha: Visualizing Vairochana,” YouTube, February 3, 2015, 2:40, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPKAJX-HnTo.

Further Resources Permalink

Rubin Museum of Art Web Resources

Artwork –Shakyamuni Budda 14th Century

Artwork – Shakyamuni Budda 16th century

Podcast – Sharon Salzburg, Mindful Meditation, The Enlightened One, Lord of the Shakya Clan, Shakyamuni Buddha

Other Resources

Robert Beer, The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols, Shambhala 2003.

Glossary Terms Permalink

In Buddhism and Bon, a buddha is understood as a being who practices good deeds for many lifetimes, and finally, through intense meditation, achieves nirvana, or ”awakening”—a state beyond suffering, free from the cycle of birth and death. “The Buddha” of our age is Shakyamuni, or Siddhartha Gautama. He is considered the founding teacher of the religion we call Buddhism. The buddha prior to Shakyamuni was called Dipamkara, and the next buddha will be Maitreya. These are known as Buddhas of the Three Times. Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhists believe that there are infinite buddhas in infinite universes, who have many bodies or emanations. Other important buddhas include Amitabha, Vairochana, Bhaishajyaguru, Maitreya, and many more.

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a being who has made a vow to become a buddha or awakened. In the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, many bodhisattvas are understood as deities with enormous powers who delay their final enlightenment, remaining in the phenomenal world to help suffering beings. Among such great bodhisattvas are Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Maitreya.

deity

Different Asian religious traditions posit different types of divine beings. Hindus generally believe in an all-encompassing God-like being, called Brahman. They also believe in a variety of other gods (deva), including Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. Early Buddhists denied the existence of a single, all-powerful creator god. Nevertheless, they always recognized a variety of powerful spirits, like gandharvas and nagas. Mahayana Buddhists came to see bodhisattvas as beings of enormous power, and buddhas themselves as cosmic beings with the ability to create entire universes. Buddhist and Bon traditions in Tibet worshiped a variety of other gods (Tib. lha), like the mountain gods, or gods of the land. According to Buddhist tradition, enlightened deities are seen as beyond the cycle of death and rebirth, whereas gods (including Hindu gods) are not.

iconography

In the Himalayan context, iconography refers to the forms found in religious images, especially the attributes of deities: body color, number of arms and legs, hand gestures, poses, implements, and retinue. Often these attributes are specified in ritual texts (sadhanas), which artists are expected to follow faithfully.

In Vajrayana Buddhism or Bon, a mandala refers to a cosmic abode of a deity, usually depicted as a diagram of a circle with an inscribed square that represents the deity enthroned in their palace, surrounded by members of their retinue. Mandalas can be painted, three-dimensional models, architectural structures, such as temples or stupas, or composed as arrangements of images within a temple. The instructions for creating and visualizing mandalas are usually found in ritual texts, such as tantras and sadhanas. Mandalas can be used in initiation ceremonies, visualized by a practitioner as part of deity yoga, consecrated and used to represent the divine presence within ritual space, offered to the deities as representations of the entire universe. A similar concept in Hinduism is a yantra.

In Hinduism and Buddhism, mudras are ritual hand gestures made by deities, Buddhas, and other sacred figures. These hand gestures are important and relatively standardized parts of deities’ iconographies. Mudras are also performed by practitioners during rituals, allowing them to take on the bodily attributes of the deities.

Tantra was a religious movement in India around the fifth to seventh centuries, and its practices are part of Buddhism and Hinduism. The word tantra also refers to texts which transmit tantric practices. In Buddhism, tantra is also called Vajrayana, “The Vajra Vehicle.” Tantric ritual and art are characterized by deity yoga, mandalas, mantras, abhisheka (initiation), wrathful deities, and ritual sexual union. In Hinduism, tantrism was often associated with the worship of Shiva and various goddesses (shakti). A practitioner of tantra is called a “tantrika.” Tantra is also a genre of texts that have been variously categorized. Most common is the division of tantras into four categories: Kriya Tantra, Charya Tantra, Yoga Tantra, and Highest Yoga Tantra.

tantric consort

In Vajrayana Buddhism, deities are sometimes portrayed as male and female couples in sexual embrace, called yab-yum (Tib. “Father and Mother”) images. They represent symbolic union of wisdom (female) with active compassion, or method (male), the two necessary elements for achieving awakening. As yidam in Vajrayana and as gods in tantric Hinduism, practitioners visualize these images in meditative deity-yoga, while manipulating the winds, channels, and chakras of the inner “subtle body.” More rarely, tantric union is practiced physically between a yogin and a consort, sometimes as part of an abhisheka initiation.

Vajrayana is one of the three great doctrinal divisions of Buddhism, along with Theravada and Mahayana. Vajrayana can be understood as tantric Buddhism. Historians debate when Vajrayana first appeared, but it was clearly understood as a separate tradition by the eighth century CE, and most of its major texts were written by the twelfth century. Vajrayana ritual and art are characterized by visualization, deity yoga, wrathful deities, mandalas, mantras, initiations and empowerments (abhisheka), and ritual sexual union. These teachings are transmitted in texts called tantras and sadhanas, as well as through secret instructions (Skt. upadesha) from a teacher. Essentially all Himalayan Buddhist traditions integrate Mahayana and Vajrayana practices.

In the Vedas, vajras are the indestructibly hard thunderbolts that Indra hurls at his enemies. Over time, the vajra became the name for a type of ritual weapon, with a handle at the center and a five-pronged point at each end. Vajras are a central image in and symbol of tantric forms of Buddhism, which are often called “Vajrayana” or the “Vajra Vehicle.” Vajrayana ritualists use vajras (representing active compassion or method) often paired with a bell (representing wisdom) in practices of deity yoga. The Tibetan word for a vajra is “dorje,” meaning “Lord among stones.”

Additional Keywords Permalink

- Awakening

- Protectors

- Female deity

- Union (yam-yum)

- Renunciation