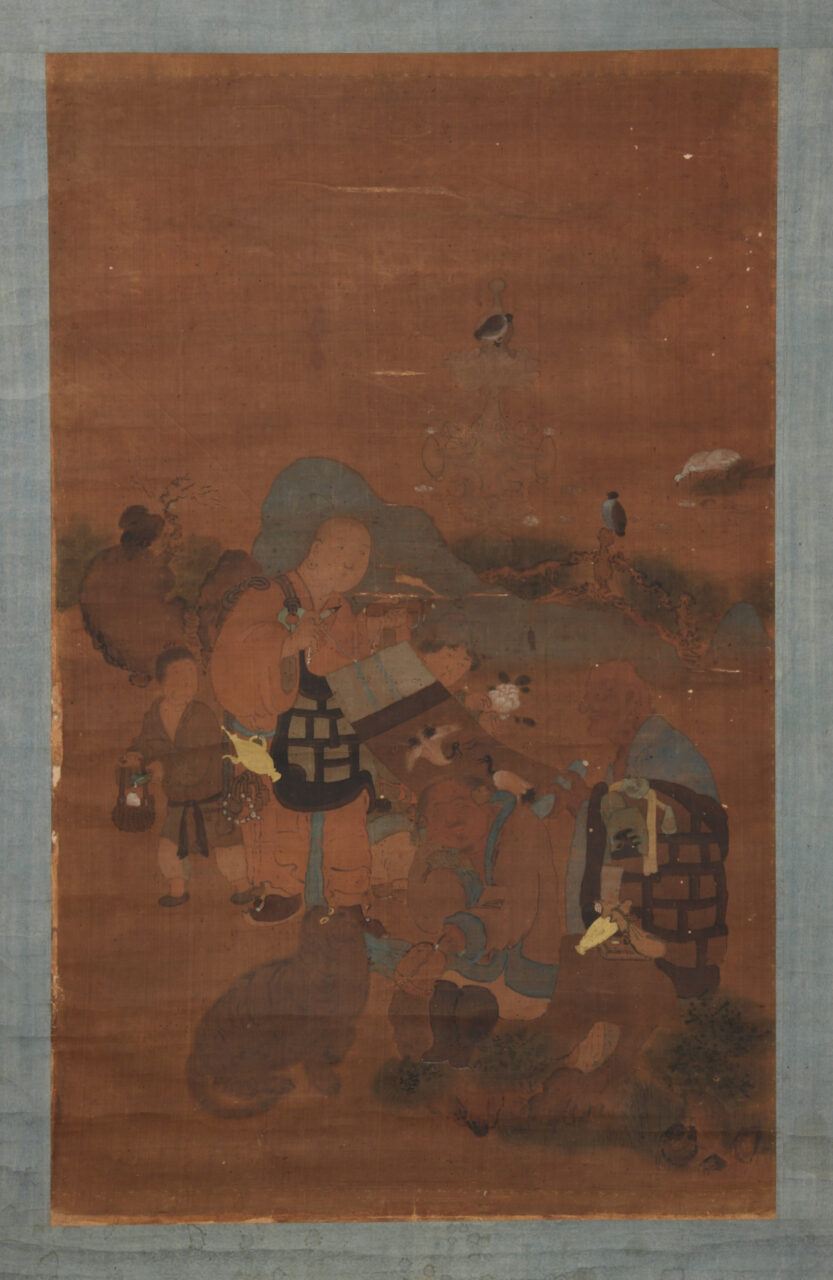

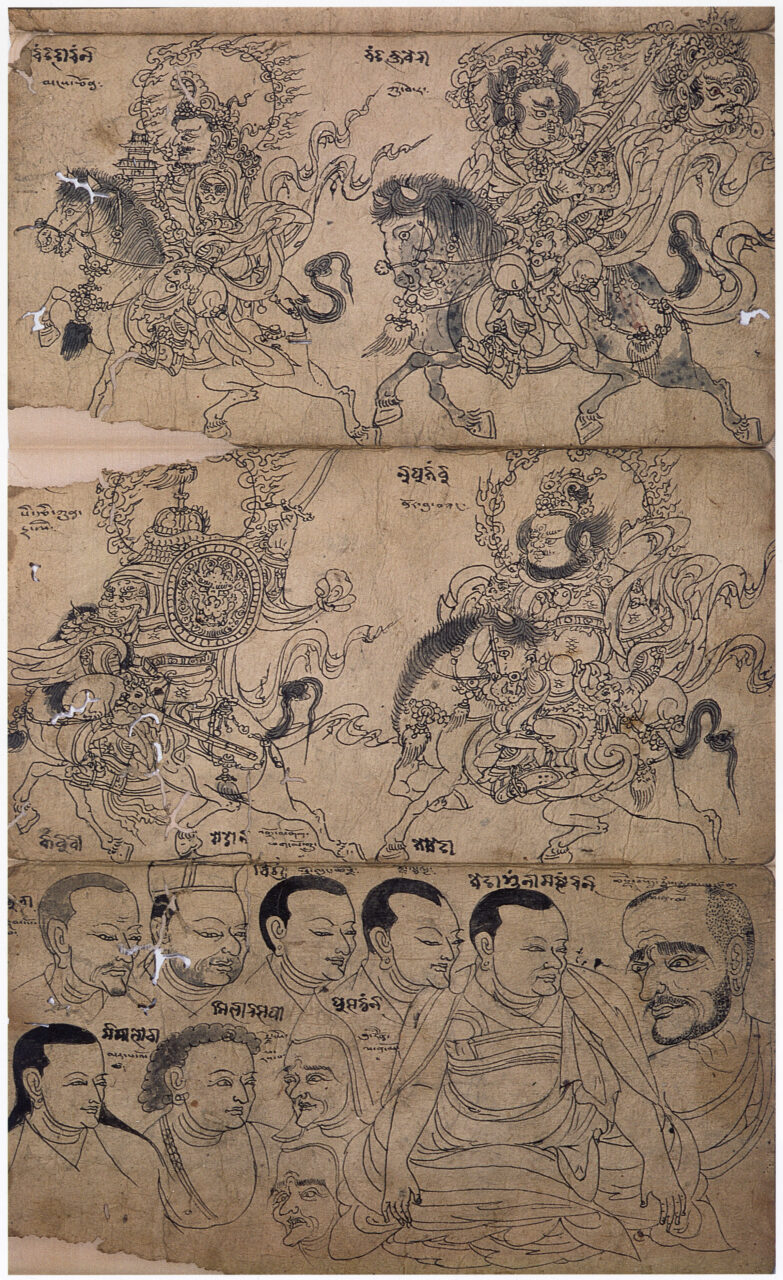

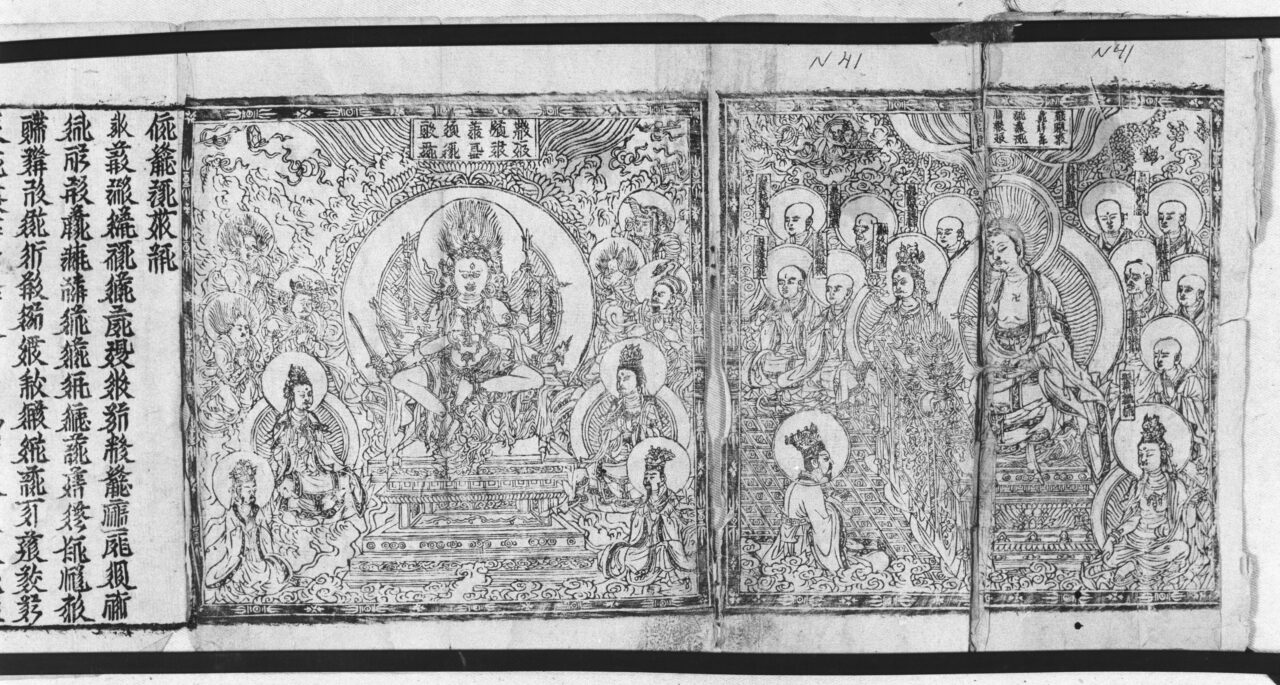

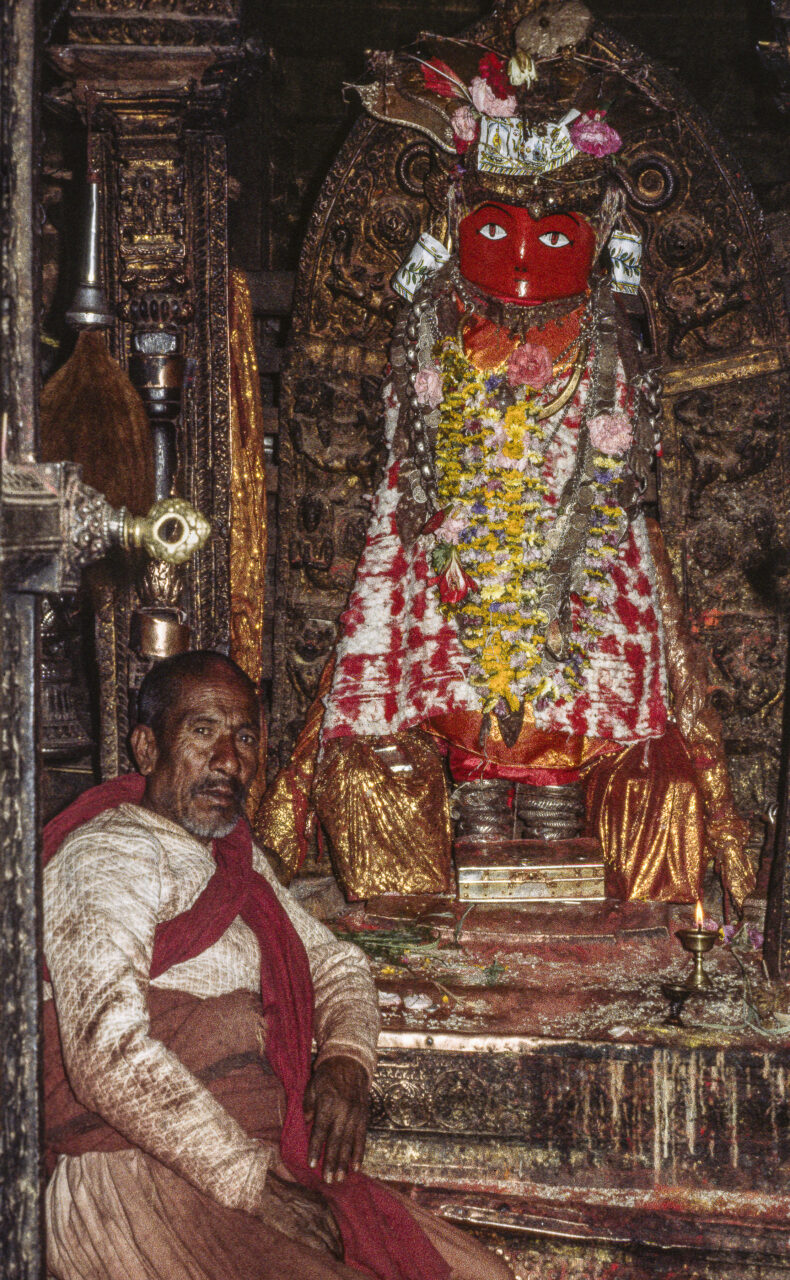

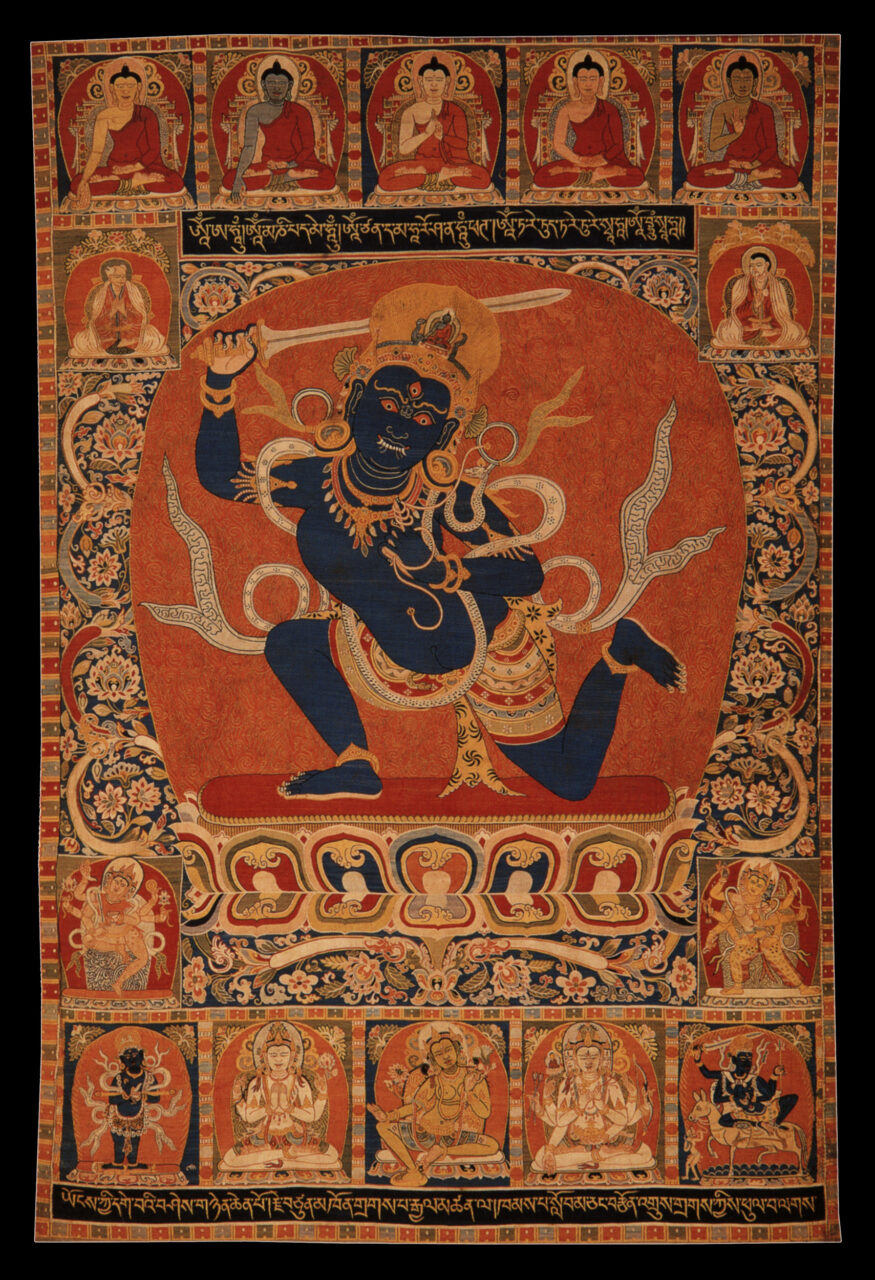

In the Himalayan context, iconography refers to the forms found in religious images, especially the attributes of deities: body color, number of arms and legs, hand gestures, poses, implements, and retinue. Often these attributes are specified in ritual texts (sadhanas), which artists are expected to follow faithfully.

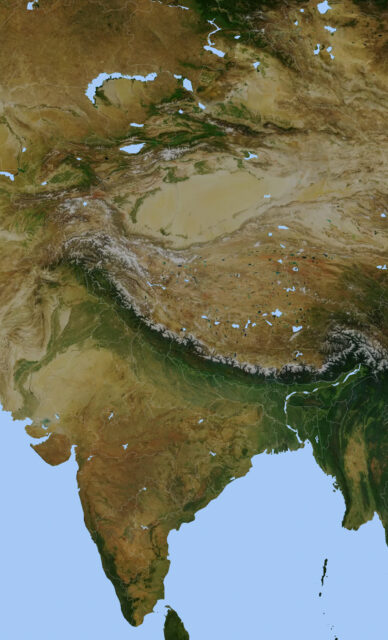

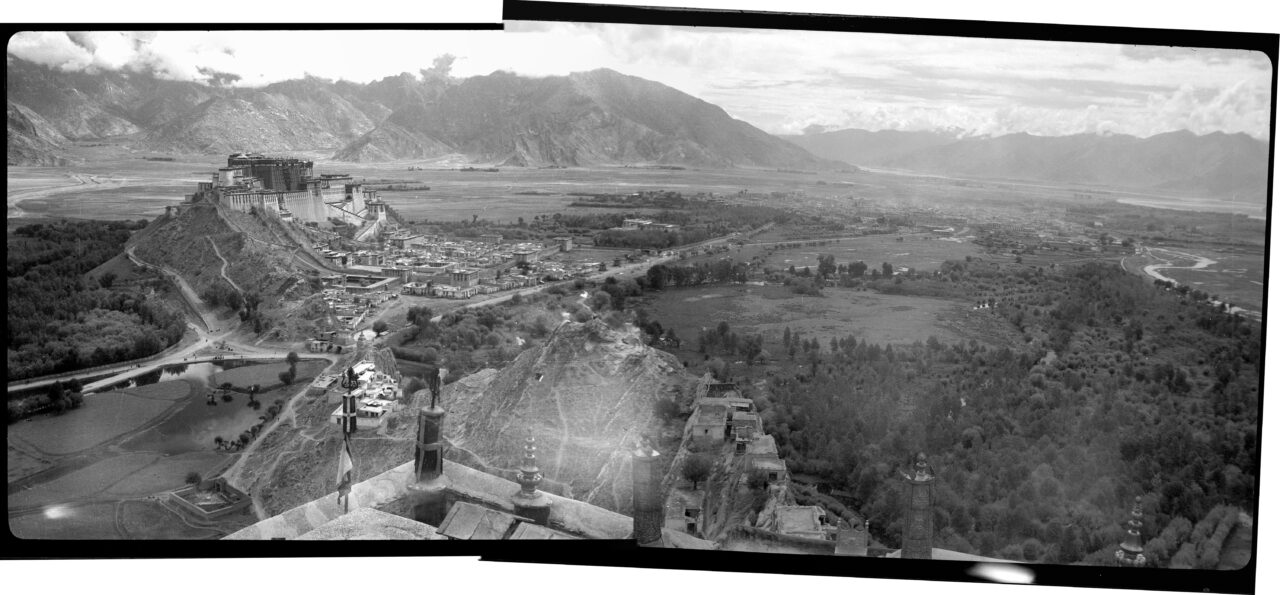

Licchavi is a name for an ancient Indic people. In the time of the Buddha Shakyamuni (sixth-fifth century BCE), the Licchavis inhabited the northern bank of the Ganges river in the area around the city of Vaishali, their capital. In the mid-fifth century CE, a branch of the Licchavis formed a dynasty in the Kathmandu Valley, and ruled there until the mid-ninth century, retaining close ties with Indian kingdoms and establishing close cultural, trade, and diplomatic relationships with both Tibet and China. The Licchavi period is known as the earliest great age of Nepalese art, with many Buddhist and Hindu bronzes and stone sculptures surviving today.

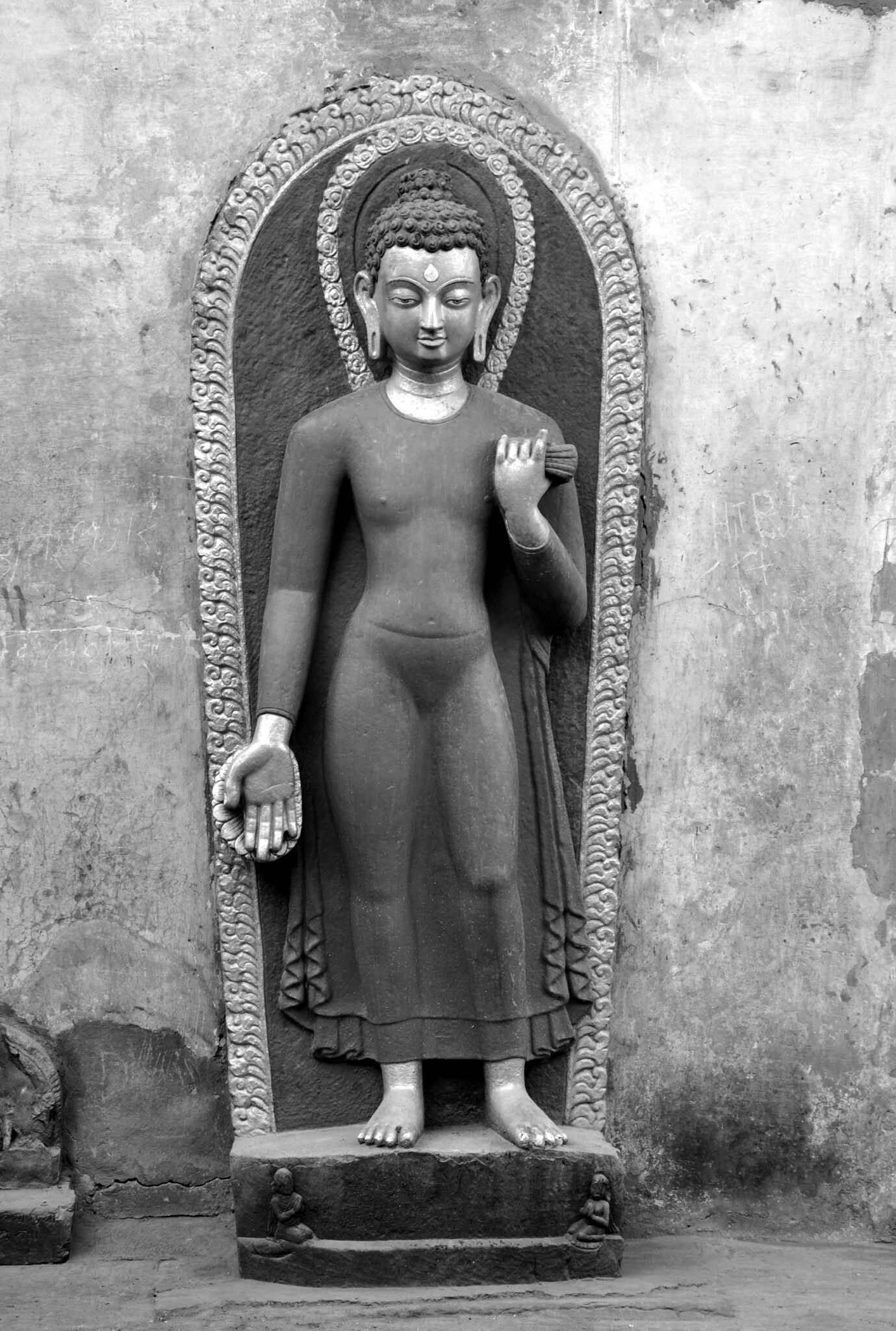

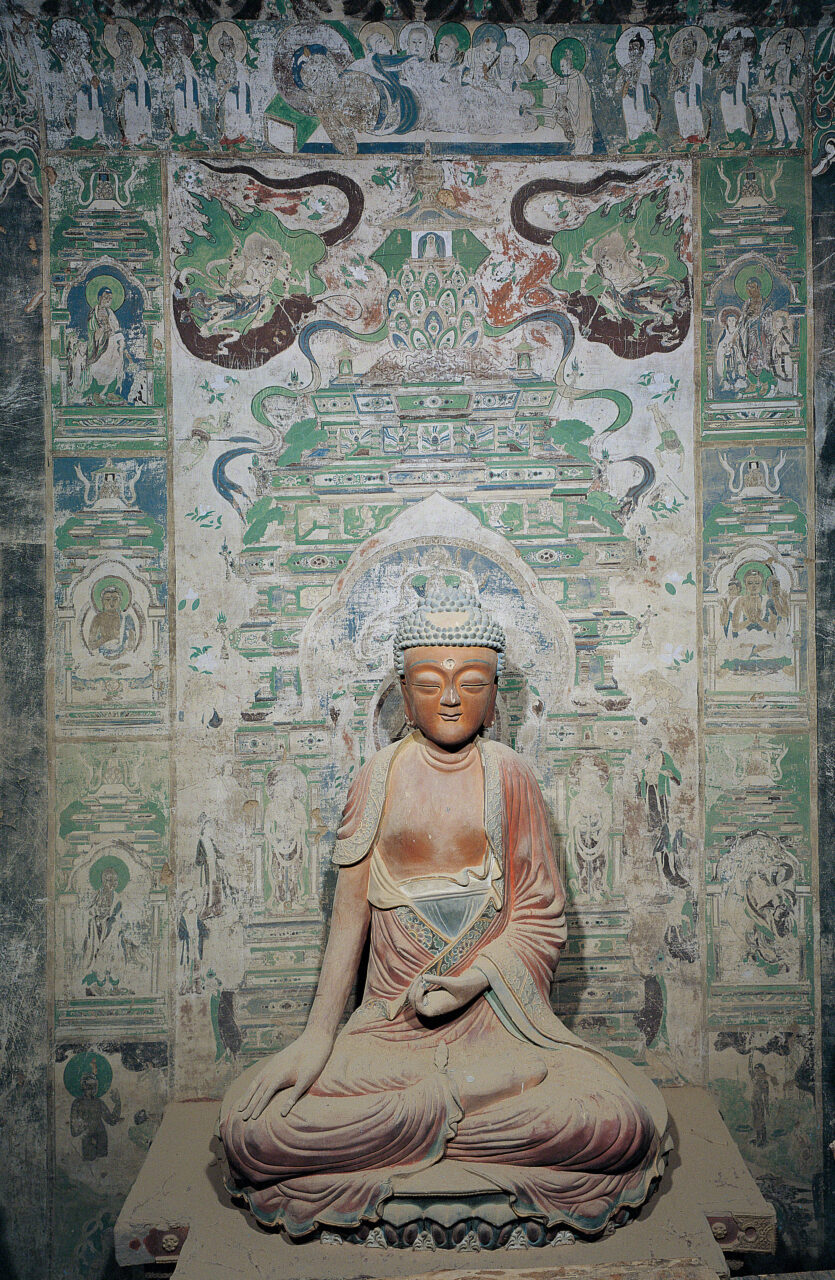

Buddhists believe that the universe expands and contracts over endless eons or “kalpas.” Buddhas appear at pre-set times in these eons. The Buddha of our era was Shakyamuni, and the next Buddha to appear will be Maitreya, whose coming will usher in an age of peace. Images of Maitreya are very popular in Buddhist art, either as part of a trinity of Buddhas of the Three Times, or as individual sculptures and paintings often depicting Maitreya standing. Maitreya can be represented both as a bodhisattva and as a buddha.

In Hinduism and Buddhism, mudras are ritual hand gestures made by deities, Buddhas, and other sacred figures. These hand gestures are important and relatively standardized parts of deities’ iconographies. Mudras are also performed by practitioners during rituals, allowing them to take on the bodily attributes of the deities.

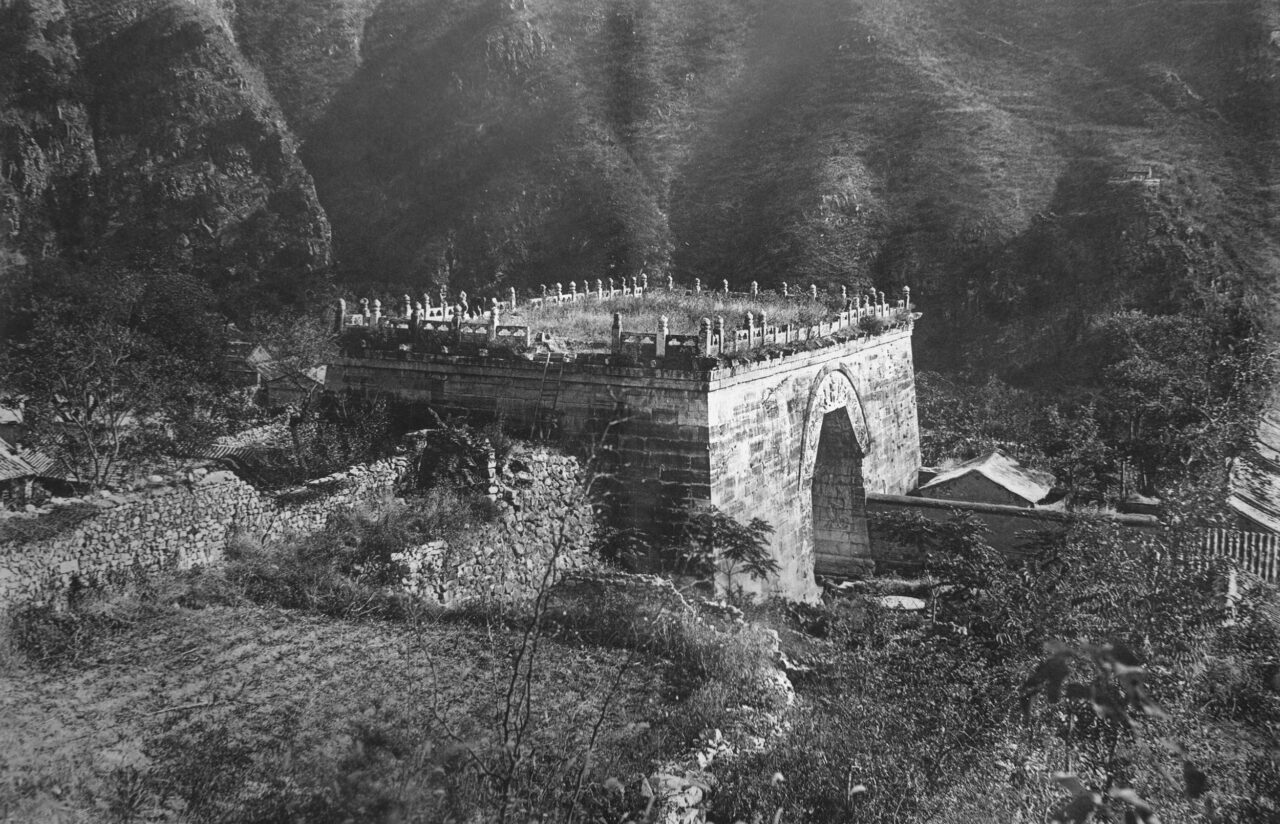

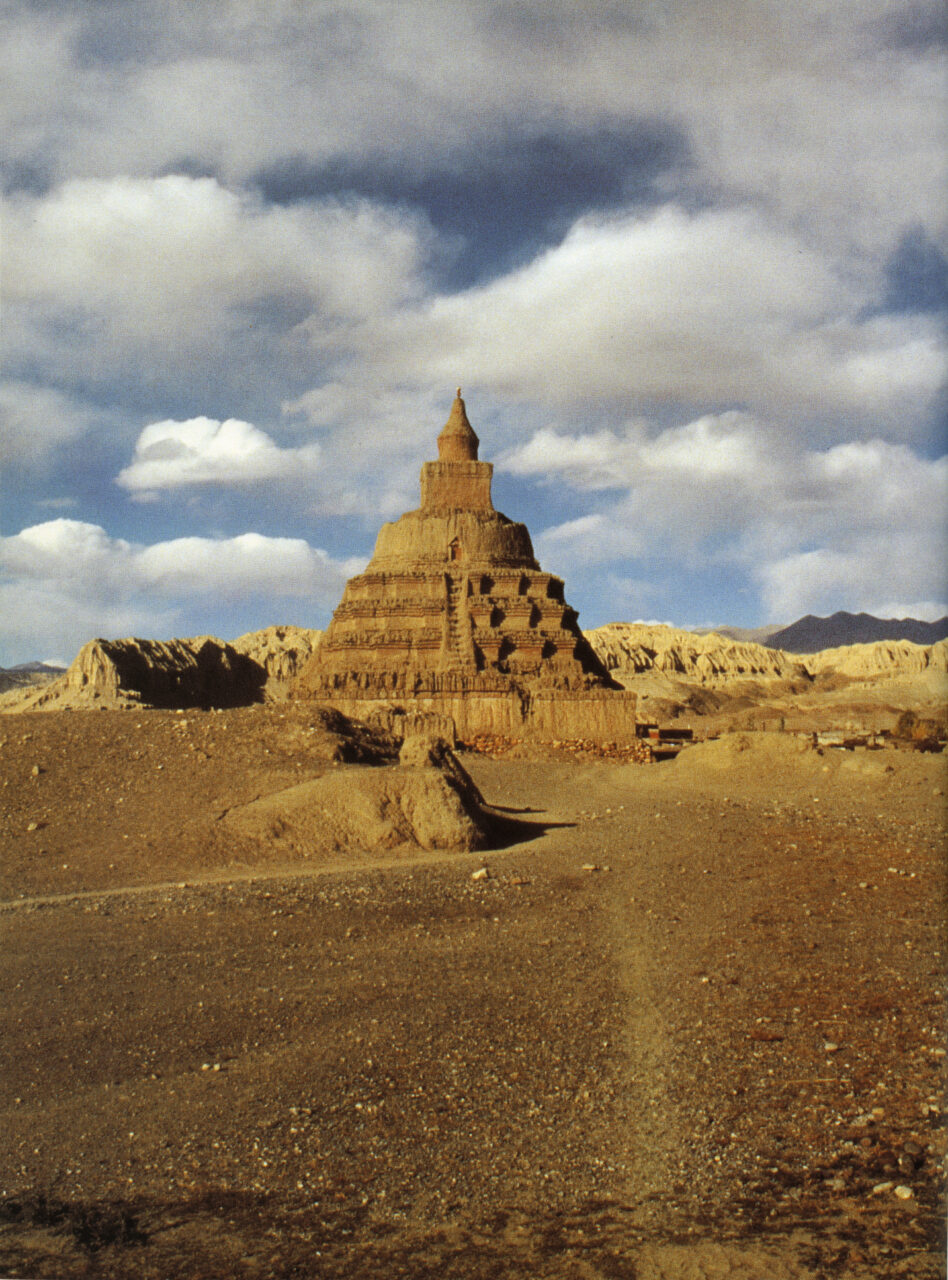

Stupas are monuments that initially contained cremated remains of Buddha Shakyamuni or important monks, his disciples, and subsequently other material and symbolic relics associated with the Buddha’s body, teaching, and enlightened mind. As representations of the Buddha’s presence in the world, stupas with their contents—texts, relics, tsatsas—continue to be important objects of Buddhist worship in their diverse forms of domed structures, multistoried pagodas, and portable sculptures. The original form of stupas was an earthen dome-shaped mound containing the remains in reliquary vessels or urns deposited within the innermost core. The dome would often be successively enlarged and surrounded by a path for a walk around in a clockwise direction and veneration (circumambulation)