Tenzin Yewong Dongchung

Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of History

Brown University

The Beginning of Tibetan Woodblock Printing in the Global History of Print Permalink

The practice of woodblock printing has deep historical roots in Eurasia. It was first recorded in seventh-century Tang China (618–907), with kingdoms in Korea and Japan soon adopting the technique in the eighth century. By the tenth century, the technology spread from East Asia to regions of South Asia and North Africa, where the medium of prints expanded from paper to textiles. Today, the earliest known Tibetan-language xylograph is dated to the twelfth century and was produced in the Tangut (1038–1227) (Tib: མི་ཉག་), a region located near the Silk Road on the eastern edges of what was once the Tibetan Empire. The Sino-Tibetan borderland areas, including and , also saw concurrent printing activities in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

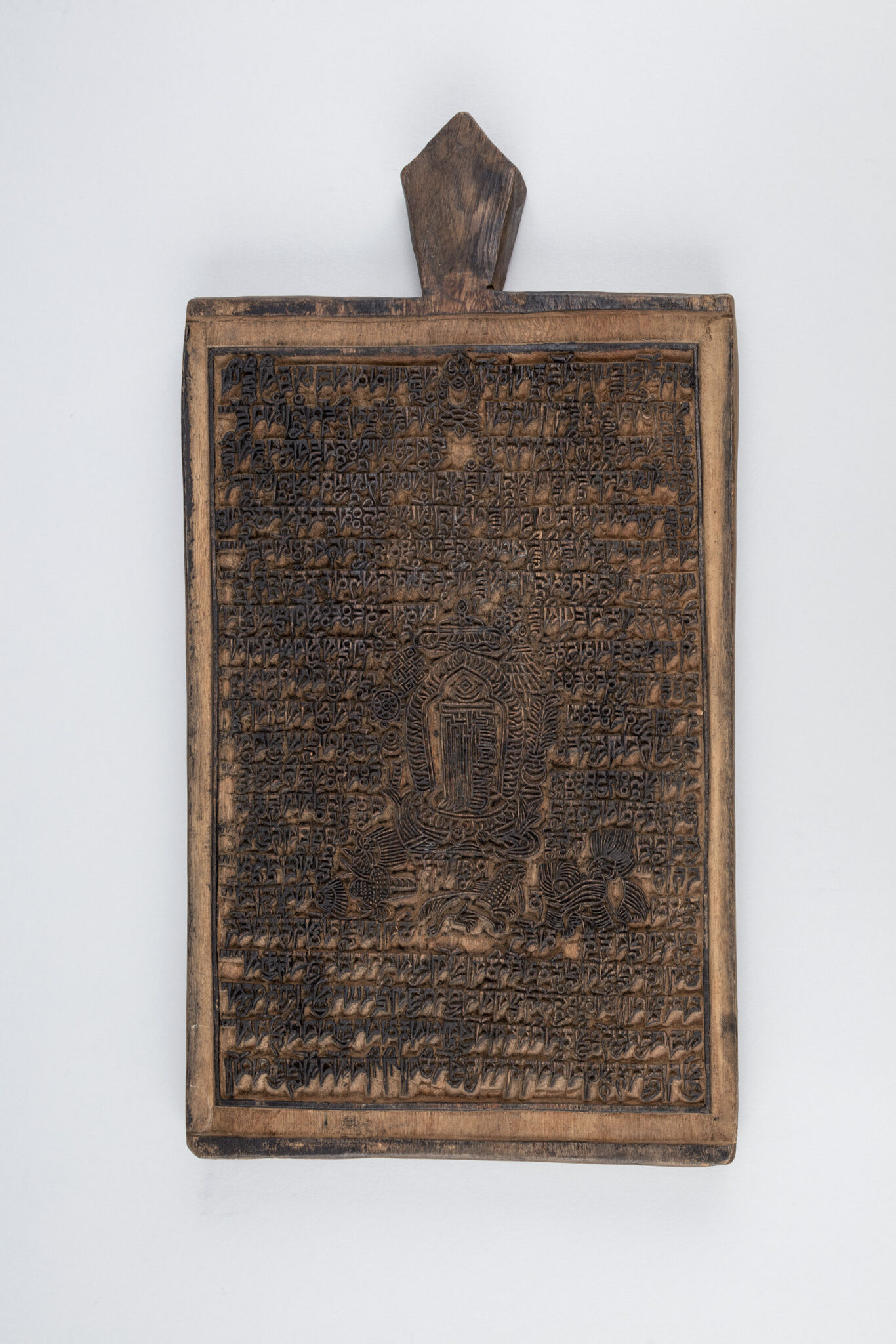

Woodblock for printing Tibetan text; Himalayan region; ca. 18th–19th century; pigments on wood; 2 1/8 × 10 5/8 × 1 in.; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2006.75.73

Even as new technologies, including lithography and movable type, later became available in the region, woodblock printing (Tib: པར་ཤིང་) remained the most dominant and consistent mode of printing in Tibet. As Tibetan ruling institutions, including monasteries and kingdoms, grew more powerful and their influence spread across Inner Asia, including and the lower Himalayan regions of India and Nepal, woodblock printing played a pivotal role in solidifying the foundations of these institutions. In addition to printing textual materials, such as pedagogical and liturgical texts, woodblocks were also carved with pictorial designs, as seen on prayer flags, , and paintings. A recurring theme across many xylographs extolled woodblock printing’s capacity to produce multiple copies. It was regarded as offering “an inexhaustible (Tib: མི་ཟད་པ་) stream of Buddhist knowledge,” underscoring the cultural factors that contributed to its enduring and consistent use in Tibet.

Woodblock for Printing Prayer Flags; Himalayan region; ca. 19th–early 20th century; pigments on wood; 14 × 7 3/8 × 1 in.; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2006.75.20

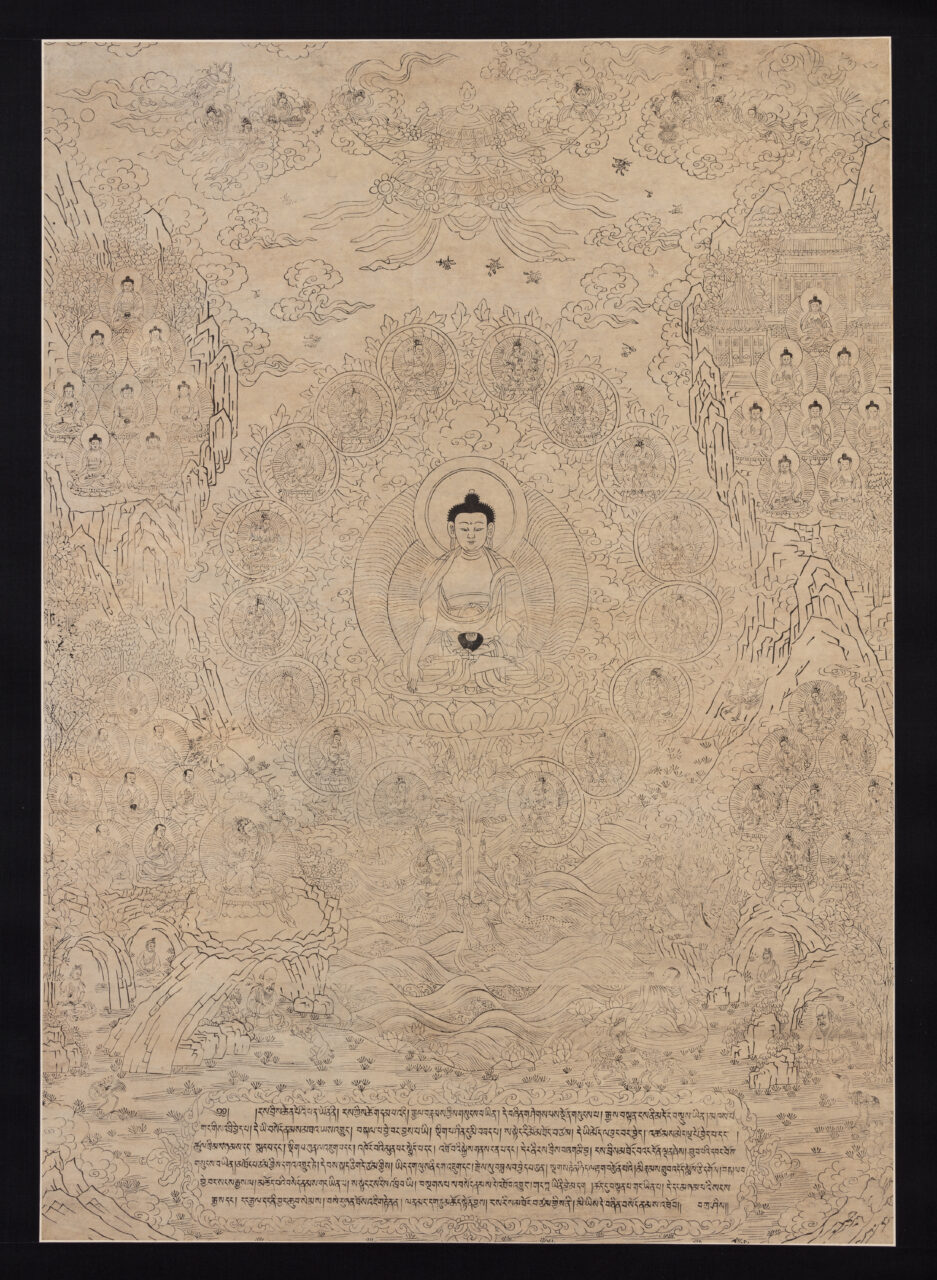

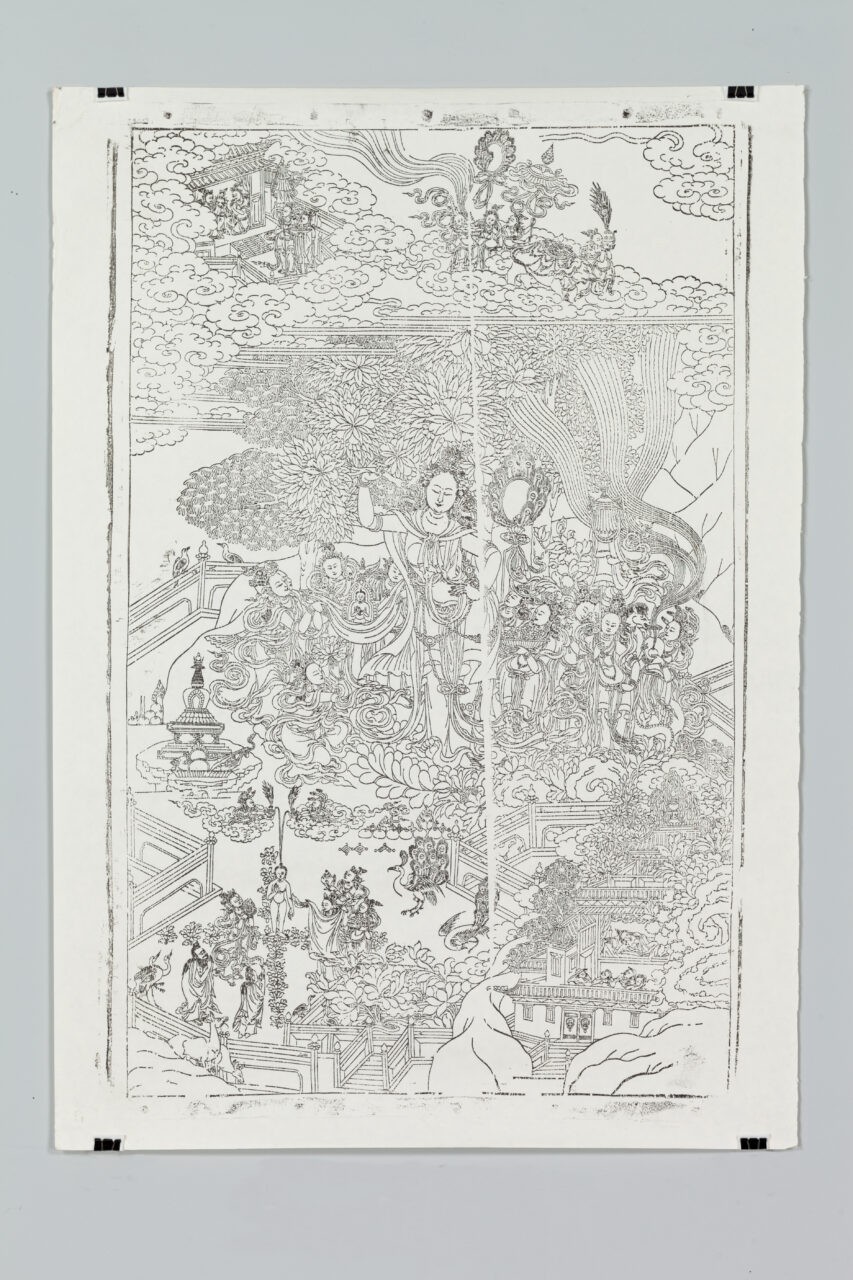

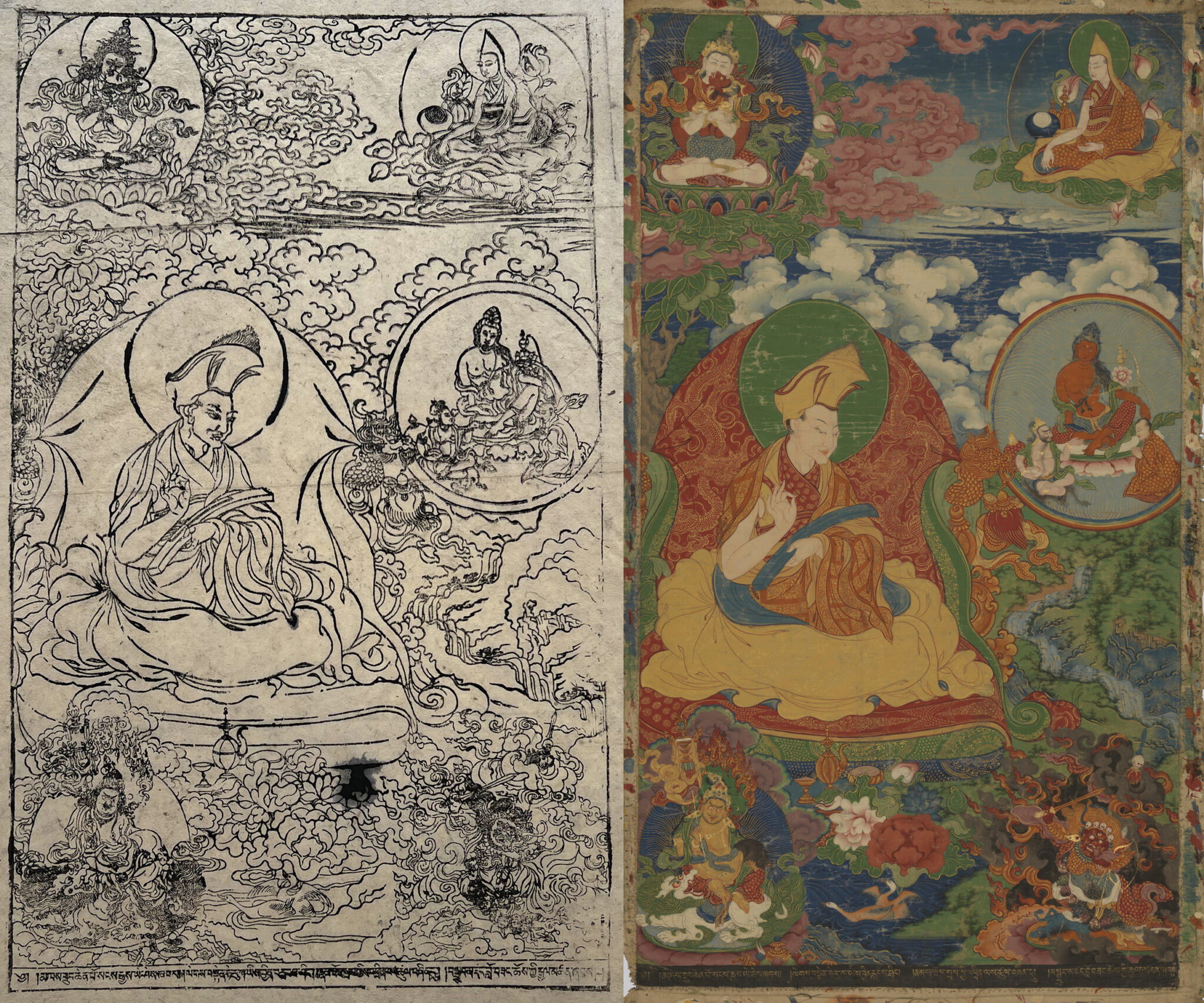

(left) Fourth Panchen Lobzang Chokyi Gyeltsen (1570–1662), after Choying Gyatso’s (act. 17th century) set of preincarnations of the Panchen Lamas; Eleventh portrait in xylographic series of the Panchen rebirth lineage; Nartang printing house, Tsang region, central Tibet; second quarter of 18th century; woodblock print, ink on paper; printed area: 26 3/16 × 16 1/8 in. (66.5 × 40.9 cm); Tucci Collection of the “Biblioteca IsIAO” – Sala delle collezioni africane e orientali, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale “Vittorio Emanuele II” di Roma; inv. no. 8155/92; photograph by Nancy G. Lin

(right) Fourth Panchen Lobzang Chokyi Gyeltsen (1570–1662), after Choying Gyatso’s (act. 17th century) set of preincarnations of the Panchen Lamas; eleventh portrait in series of the Panchen rebirth lineage, copied from Nartang xylographic design; Tsang region, central Tibet; 18th century; pigments on cloth; 27 × 15½ in. (68.6 × 39.4 cm); Rubin Museum of HimalayanArt; Gift of the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation; F1996.21.2 (HAR 477)

Centralization and State Building in Central Tibet (15th–17th century) Permalink

In the fifteenth century, Tibetan-language printing saw a shift in its patronage, moving from the Tangut Xixia kings and emperors to the Tibetan kingdoms of , , and . This shift was characterized by rulers collaborating with monasteries, which, in turn, projected centralized power by creating or acquiring Buddhist collections. One of the most significant developments of the fifteenth century was the Yongle emperor’s (1360–1424) patronage of a copper-printed, gold-lettered in in 1410.

Sutra Covers with the Eight Buddhist Treasures, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Yongle period (1403–1424), China; red lacquer, incised decoration, gold inlay; L. 28 1/2 in. (72.4 cm); W. 10 1/2 in. (26.7 cm); H. of each cover 1 1/4 in. (3.2 cm); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015, 2015.500.1.52a, b

This set a powerful precedent, as, centuries later, many regional monasteries with aspirations to assert centralized authority began printing their own canons using woodblocks. An already established manuscript culture facilitated the adoption of this technology, as many of the skills required for printing processes, such as those of scribes and proofreaders, were already prevalent in the region. Thus, the presence of artisanal skills found an opportune moment in the fifteenth century, when monastic centralization and royal patronage led to the establishment of new printing houses in Central Tibet.

By the sixteenth century, all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism (, , , and ) had established their own monasteries. As a result, sectarian competition led these monasteries to produce printed versions of their most important texts. The nature of the texts depended on a combination of what the local rulers desired and what the monasteries deemed important to systematize. However, the growth of printing houses in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries can be attributed to the rapid and massive expansion of Geluk monasteries in the previous century. The reformist doctrines of Jé Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) garnered a substantial following and attracted affluent patrons, including the ruling Pakmodrupa family. The Geluk monasteries of Sera (1419), Ganden (1409), and Drepung (1416) were founded in the U region, while Tashilhunpo (1447) was established in Tsang.

Locations of major Geluk monasteries founded in the U region and Tsang in the 15th century.

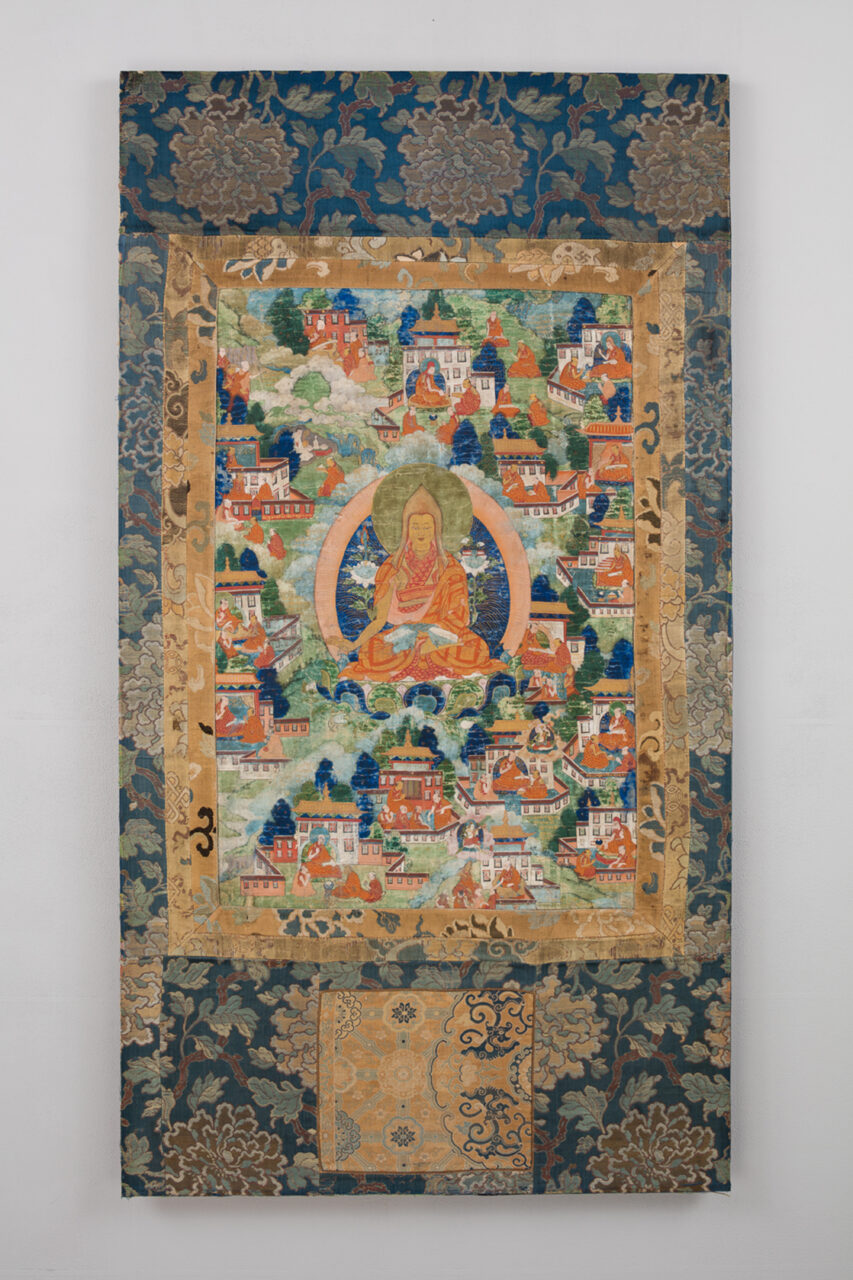

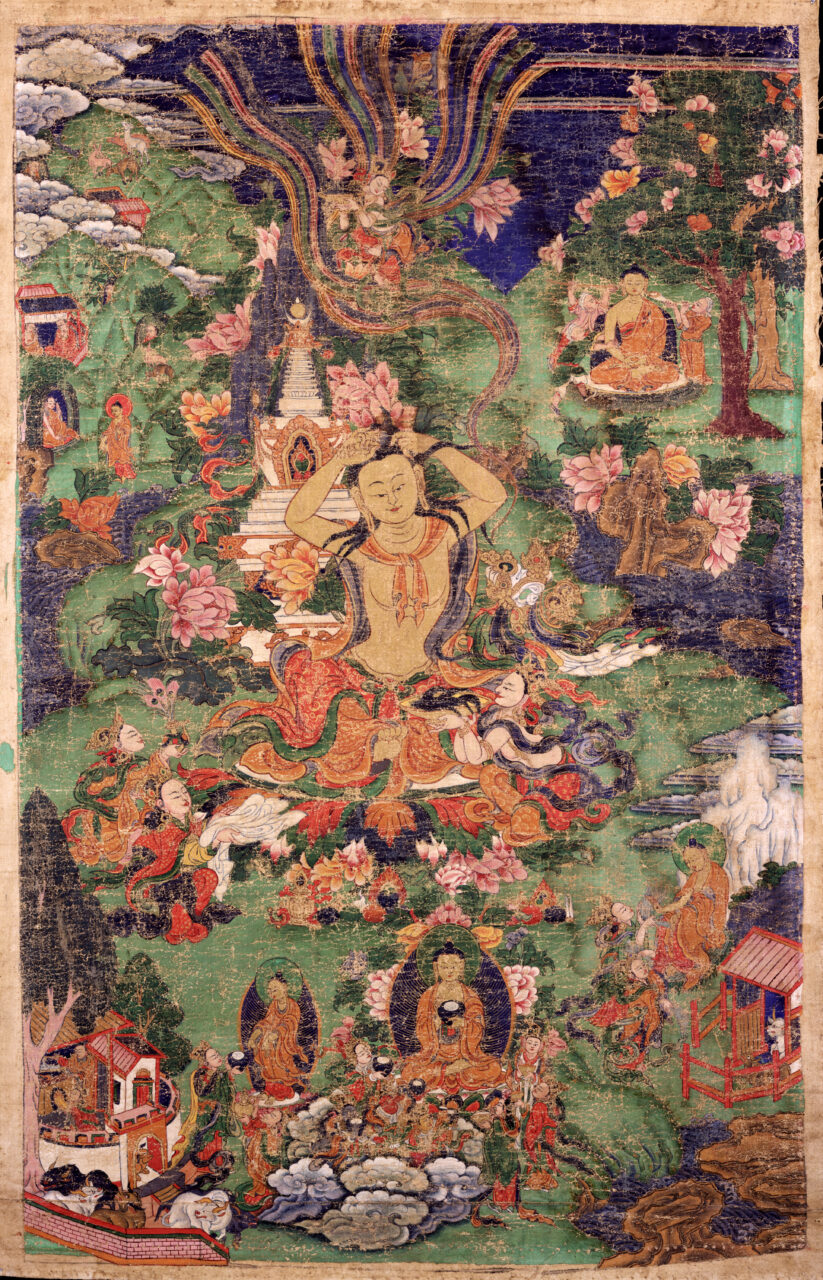

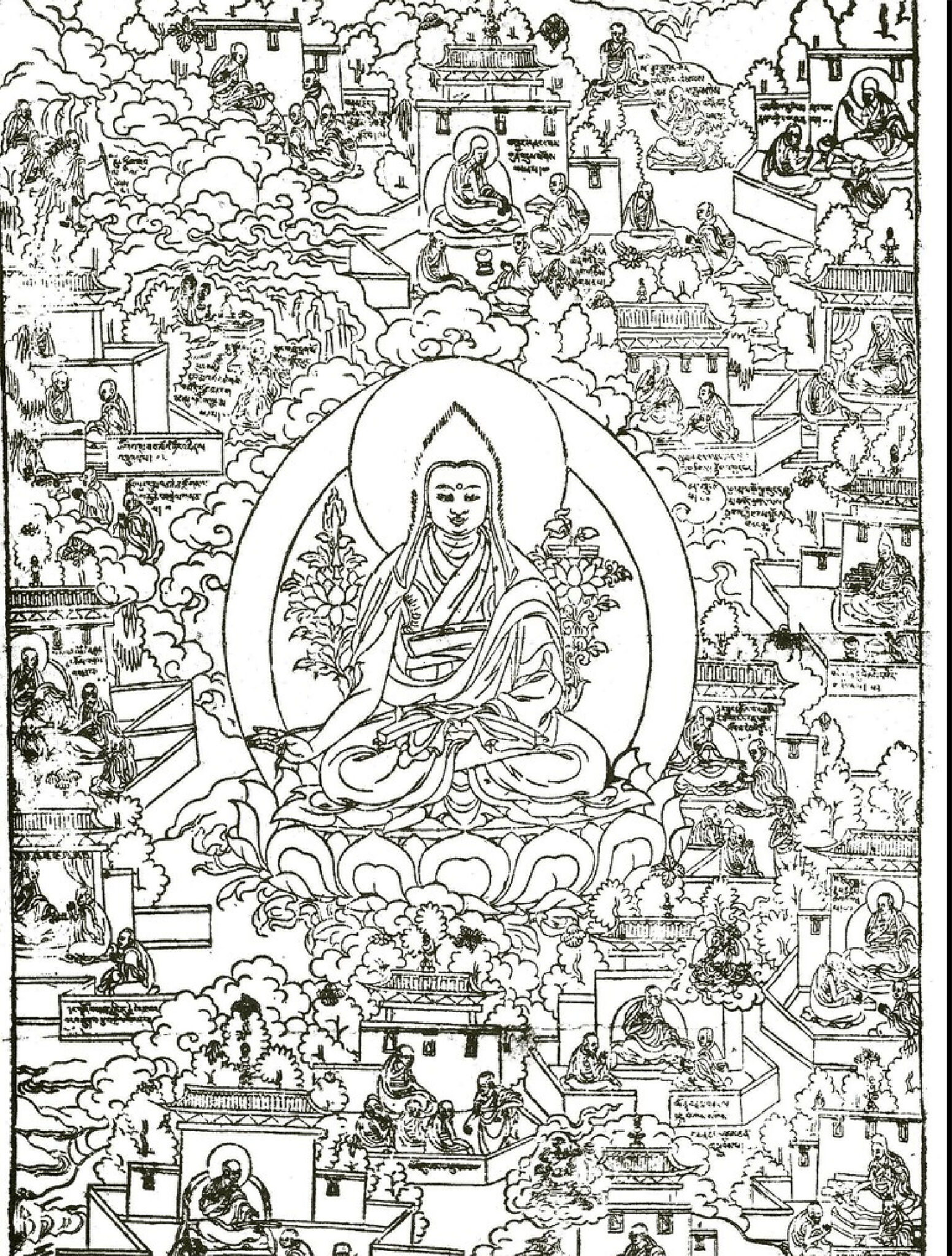

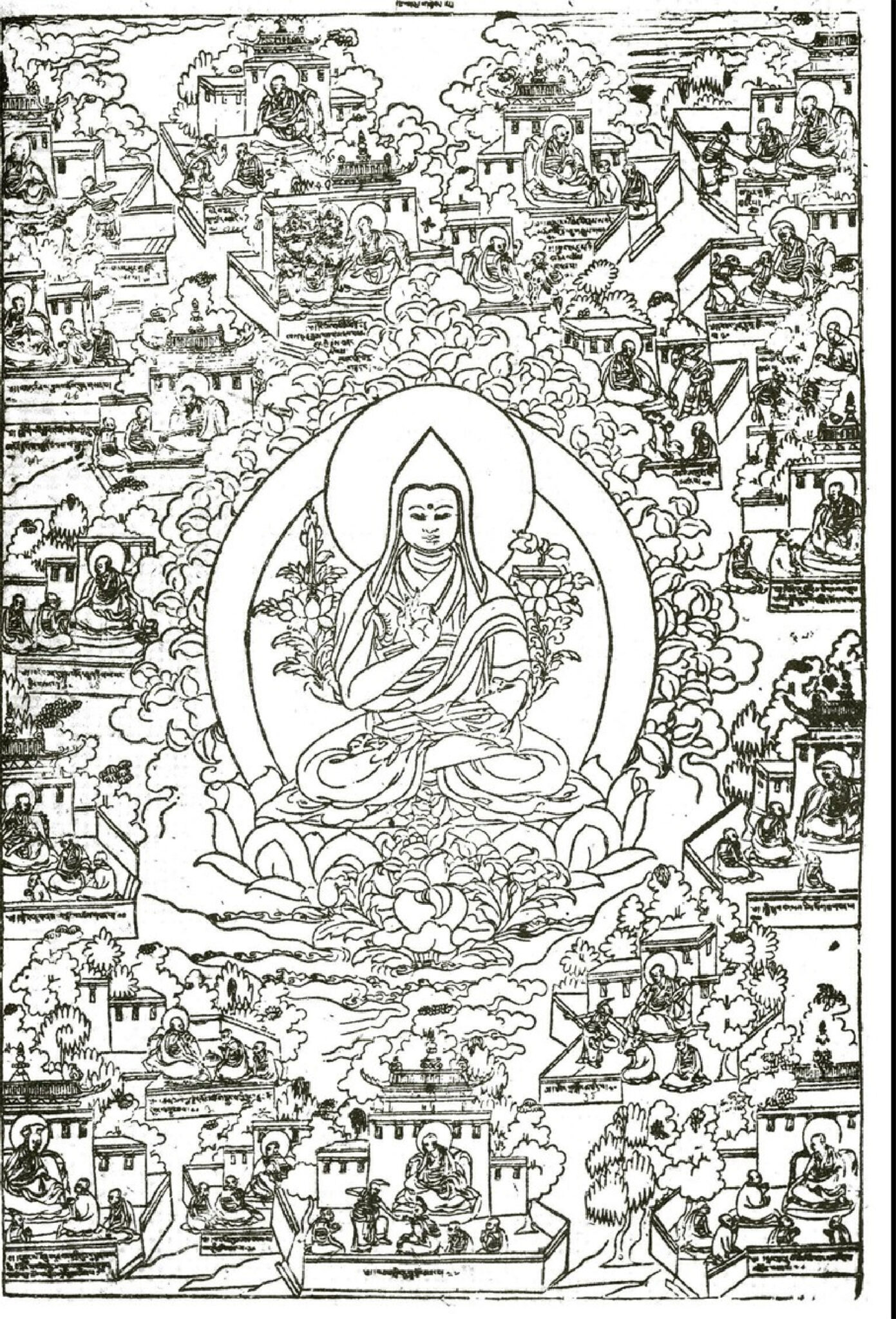

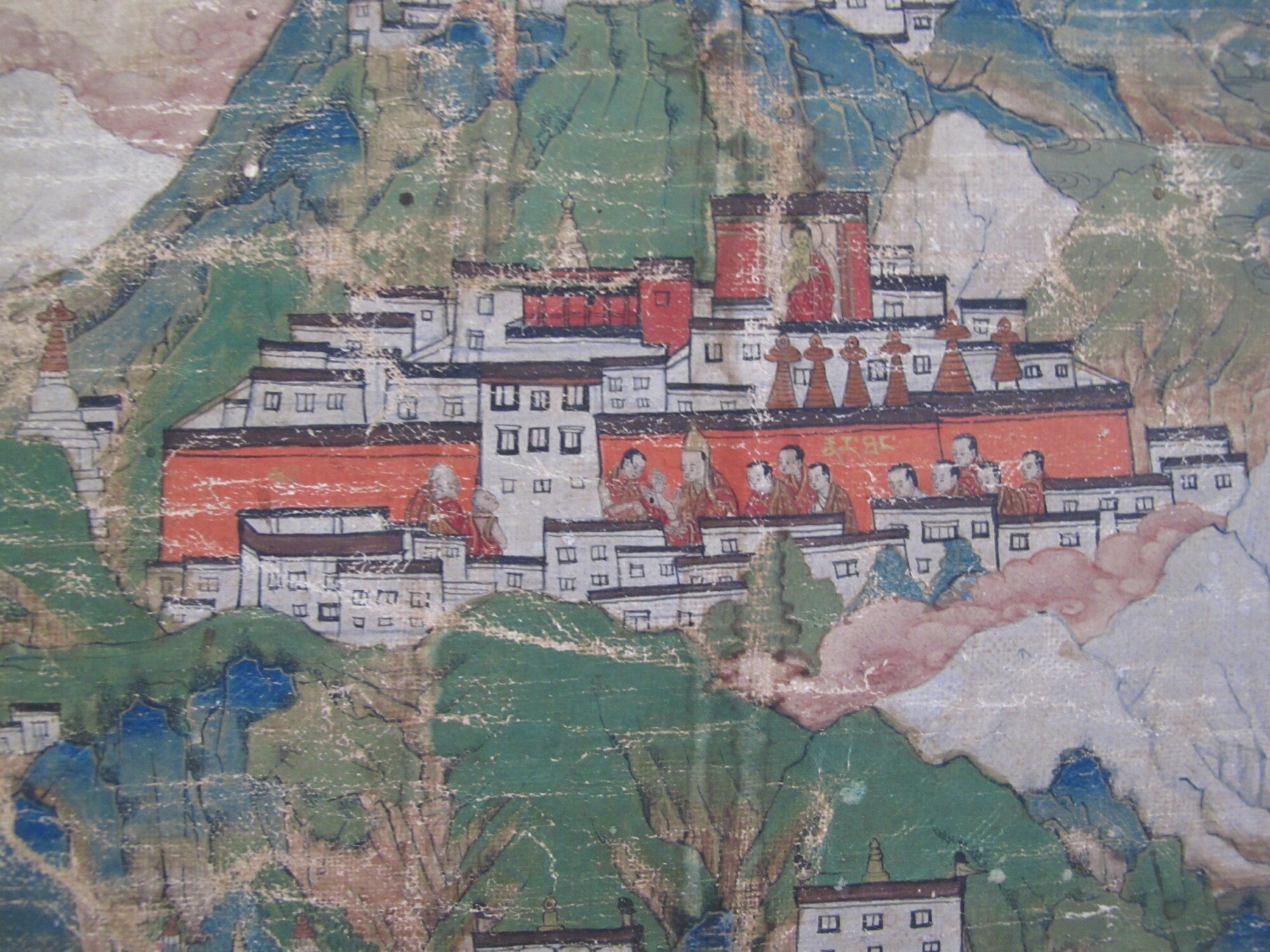

Over the course of the sixteenth century, these three Geluk monasteries expanded to the point that their administrations functioned like modern universities, with multiple colleges. Due to the Geluk emphasis on scholasticism and massive monasteries, Geluk printing houses spread most extensively in central Tibet between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Below are two examples of painted prints from Tashilhunpo and their woodblock print versions.

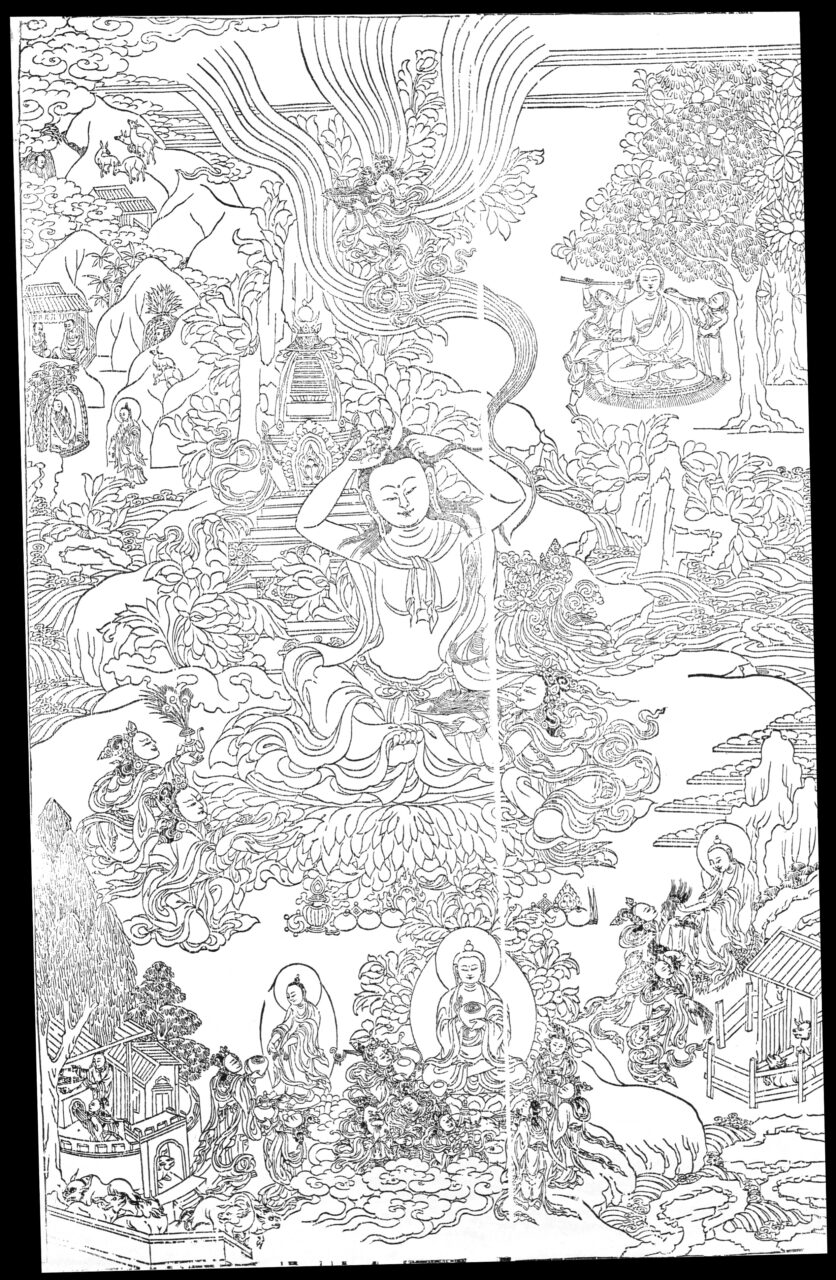

Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) and Scenes from His Life; Tibet; 18th century; painted woodbloack print, pigments on cloth, silk brocade; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Gift of the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation; F1996.23.1

Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) and Scenes from His Life (woodblock print version); paper; private collection; HAR 79008

Tsongkapa (1357–1419); Tibet; 18th century; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Gift of the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation; F1996.23.2

Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) and Scenes from His Life (woodblock print version); paper; private collection; HAR 79007

Eighteenth and Nineteenth-century Printing on Sino-Tibetan Borderlands Permalink

In the eighteenth century, Chone, Nartang, and Derge each printed the entire Tibetan Buddhist canon. These projects were enormous financial and material undertakings, reflecting both the economic capacity of these sites and the growing political ambitions of each Tibetan kingdom. Despite the consistent growth of new printing houses in Central Tibet, Kham’s expansion was the most significant in the eighteenth century.

The printing houses that published the entire Tibetan Buddhist canon in the eighteenth century.

Nartang Printing House Permalink

Derge Printing House Permalink

Derge Printing House (Parkhang) exterior; photo by Karl Debreczeny, 2001

Derge Printing House (Parkhang) woodblocks; photo by Karl Debreczeny, 2001

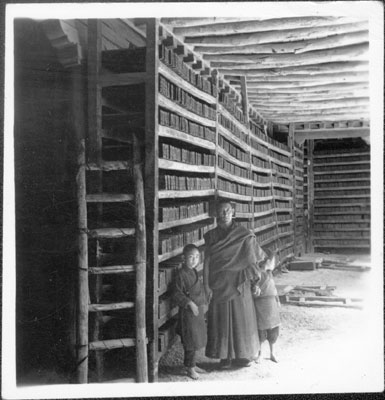

Derge Printing House (Parkhang) interior; photo by Karl Debreczeny, 2001

Derge Printing House (Parkhang) cleaning blocks; photo by Karl Debreczeny, 2001

As the (1644–1911) began to expand into new territories in Inner Asia, the region that makes up today’s province emerged as an important frontier. Its rise as a key strategic area in the eighteenth century served as the primary impetus for its socioeconomic development. With new economic resources and a decentralized political structure composed of multiple kingdoms, the southeastern region of Kham maintained a more eclectic and nonsectarian approach to production. In addition to Geluk works, texts from the Sakya, Nyingma, and Kagyu traditions were also printed in the region between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Monk Lhundrub, engraver of Sanggai Aimag (Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia); Panoramic Map of Mount Wutai; Cifu Temple, Mount Wutai, China; 1846; woodblock print on linen, hand colored; 47 1/8 × 68 in. (119.7 × 172.7 cm); Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Gift of Deborah Ashencaen; C2004.29.1 (HAR 65371)

Just as the Qing produced Tibetan-language canons in its imperial workshops in Beijing, the emperors also extended their patronage of Tibetan Buddhism towards the Northwest borderlands. Flourishing under this patronage, Geluk monasteries and new reincarnate lamas expanded rapidly in Amdo and Mongolia. These new monasteries, similar to those in sixteenth-century Central Tibet, were eager to establish themselves as new centers of Geluk power in the Inner Asian landscape. By the nineteenth century, Geluk monasteries in the Amdo region had become complex and powerful institutions, undertaking massive and diverse printing projects that ranged from the collected works (Tib.: sungbum) of reincarnate lamas to historical, medical, and bilingual Mongolian-Tibetan texts.

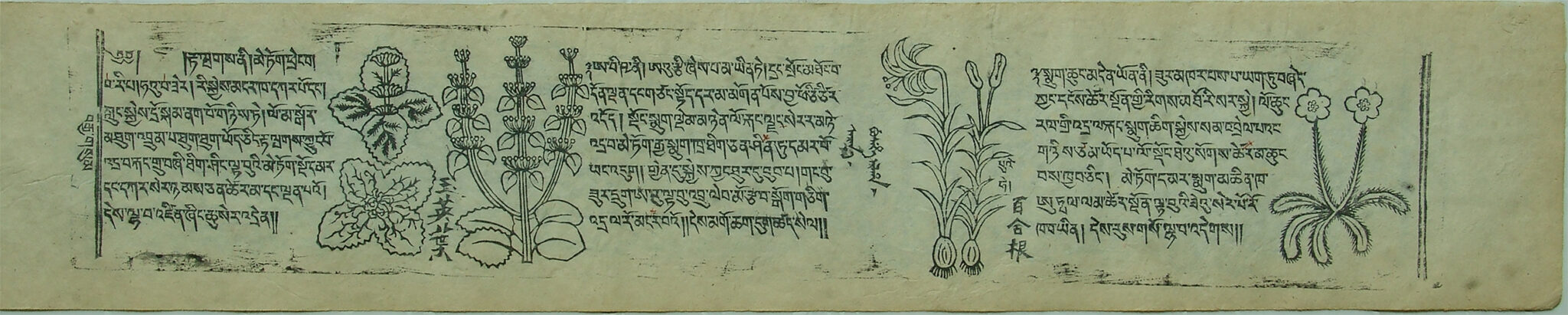

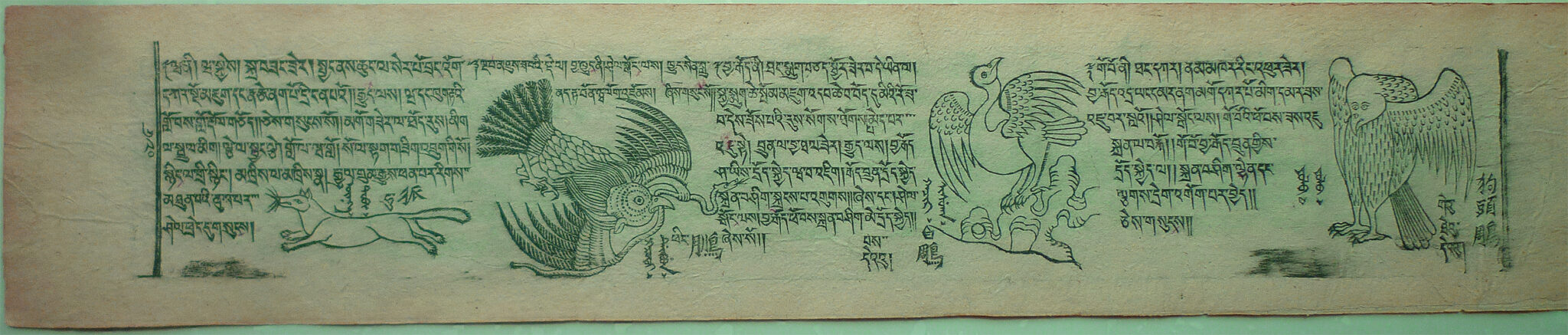

Herbal Medicines. From Naiman Jambal Dorji’s Materia Medica text, Beautiful Marvelous Eye Ornament, Part I, folio 103r. Mongolian Edition (origin unknown); 19th century; xylograph, ink on paper; 174 ff; 21 1/2 × 4 in. (54.5 × 10.3 cm); Private collection, Mongolia

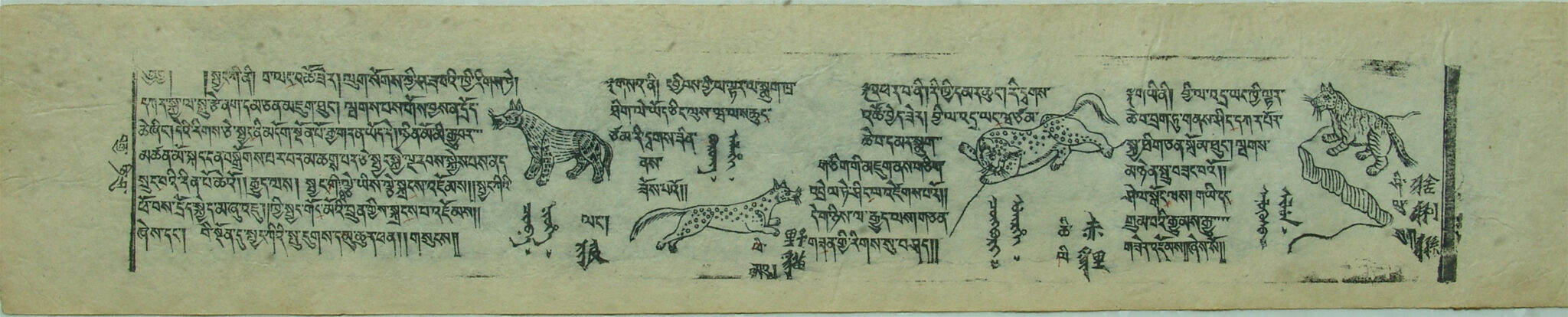

Medicines Derived from Wild Animals. From Naiman Jambal Dorji’s Materia Medica text, Beautiful Marvelous Eye Ornament, Part I, folio 120r. Mongolian Edition (origin unknown); 19th century; xylograph, ink on paper; 174 ff; 21 1/2 × 4 in. (54.5 × 10.3 cm); Private collection, Mongolia

Magical Animals. From Naiman Jambal Dorji’s Materia Medica text, Beautiful Marvelous Eye Ornament, Part I, folio 120v. Mongolian Edition (origin unknown); 19th century; xylograph, ink on paper; 174 ff; 21 1/2 × 4 in. (54.5 × 10.3 cm); Private collection, Mongolia

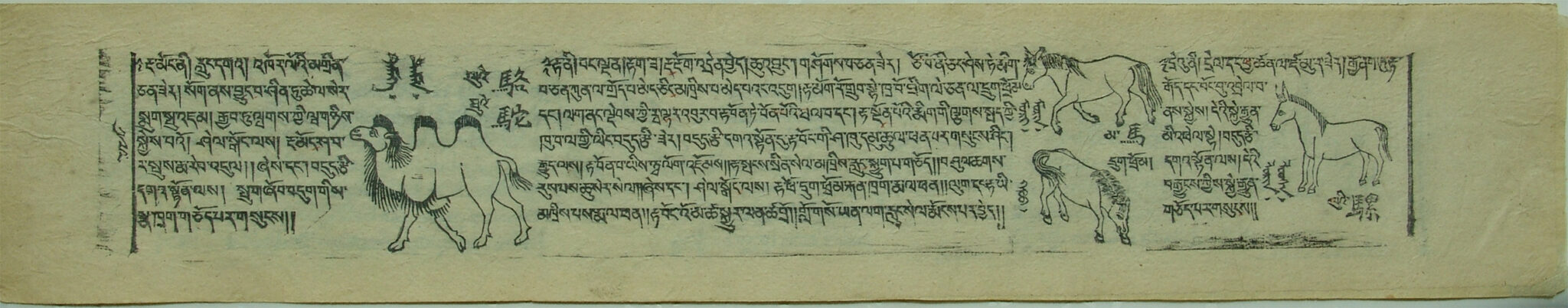

Domestic Animals. From Naiman Jambal Dorji’s Materia Medica text, Beautiful Marvelous Eye Ornament, Part I, folio 122v. Mongolian Edition (origin unknown); 19th century; xylograph, ink on paper; 174 ff; 21 1/2 × 4 in. (54.5 × 10.3 cm); Private Collection, Mongolia

Woodblocks in Monasteries and Museums Permalink

While woodblock printing technology was embraced for its ability to produce fast and multiple reproductions, Tibetan Buddhist monasteries also considered the possession of woodblock collections a matter of prestige in itself. The blocks were seen as durable, knowledge-producing objects. As a result, a large portion of the printing houses was allocated to the proper storage and maintenance of the woodblocks. Today, many of these blocks, albeit individually, can be found in the collections of numerous museums in the West and, to a lesser extent, in research universities.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, various European travelers, enamored by the narratives of Tibet as a forbidden land, sought to enter the country. Among the objects they collected were woodblocks, which can be found in the ethnographic collections of Swedish, French, and Danish museums. However, the scale of Tibetan material acquisition in the West was most strongly influenced by the 1903–4 Younghusband Expedition to Tibet, which led to the influx of Tibetan material culture into European museums and private collections, such as the British Library. Many of these public museums first emerged in the late nineteenth century and built their holdings from loot acquired during colonial enterprises. Establishing systematic institutions to categorize and represent different cultures allowed new colonial hegemonic powers to order relations among those cultures.

American ethnographic museums as the Newark Museum, Field Museum, and the American Museum of Natural History began collecting Tibetan materials in the first half of the twentieth century. The growing market for Asian art and exotica, along with the popularity of Tibetan Buddhism, led to the purchase of many thangkas and Buddhist ritual objects by institutions such as museums and auction houses as well as individuals ranging from private collectors, Buddhist practitioners, and travelers to the Himalayan regions of India, Nepal, Bhutan, and China. While woodblocks were not as popular as thangkas, ritual objects, and rare texts, art collectors and traders often bought individual pieces. Written records on the woodblock collection at the American Museum of Natural History provide the clearest insight into the museum’s interest in these objects. The sinologist Berthold Laufer (1874–1934) was sent on the Jacob H. Schiff Expedition to China to make an ethnographic record of “a sophisticated people who had not yet experienced the industrial transformation.” Today, digital collections, such as those at the American Museum of Natural History and the Museum of Ethnography in Sweden, offer the space to view objects that would otherwise remain hidden, echoing James Clifford’s view that “collections and displays [are] unfinished historical processes of travel, of crossing and recrossing.”

Objects Related to Woodblock Printing in the Rubin's Collection Permalink

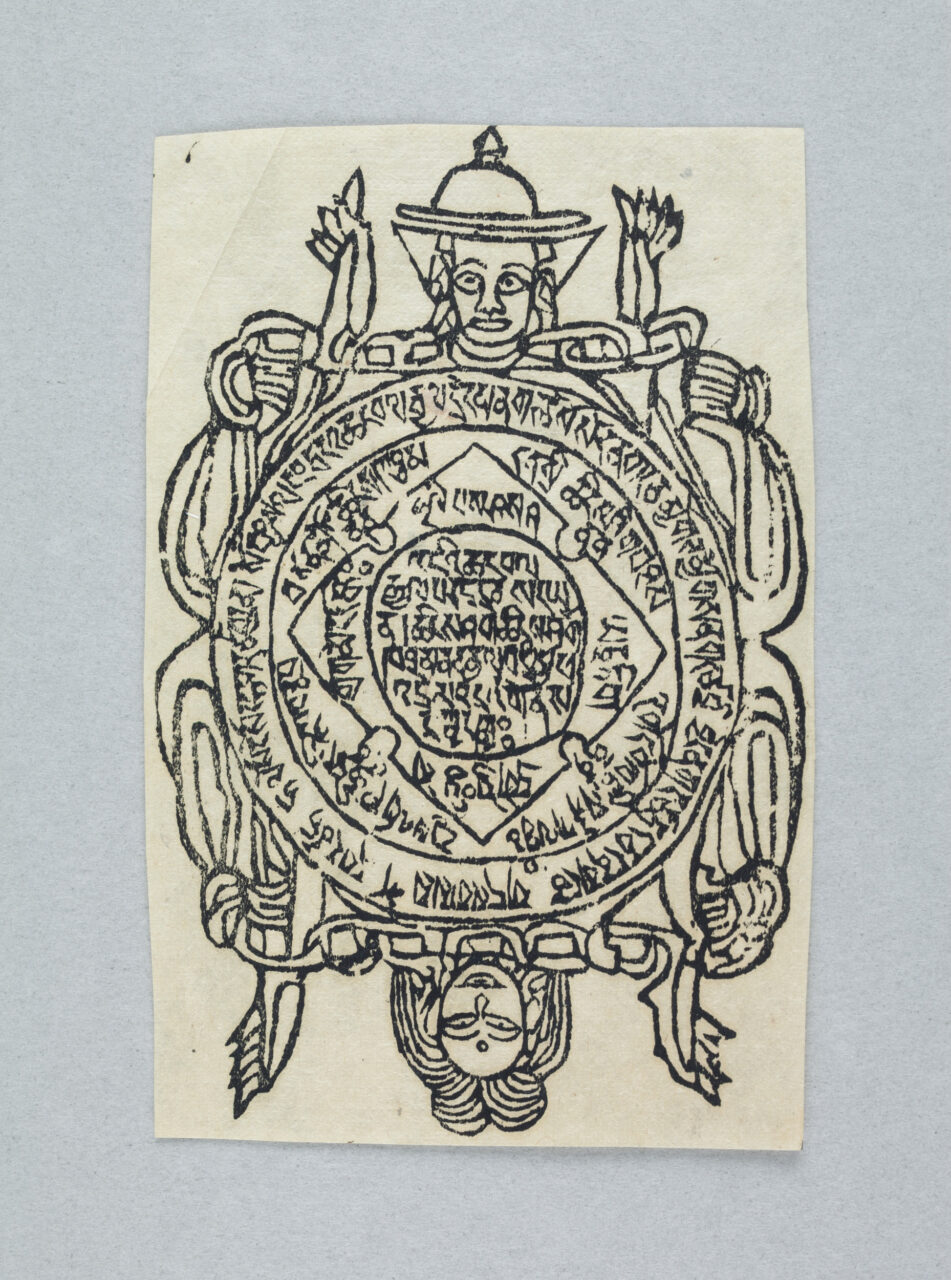

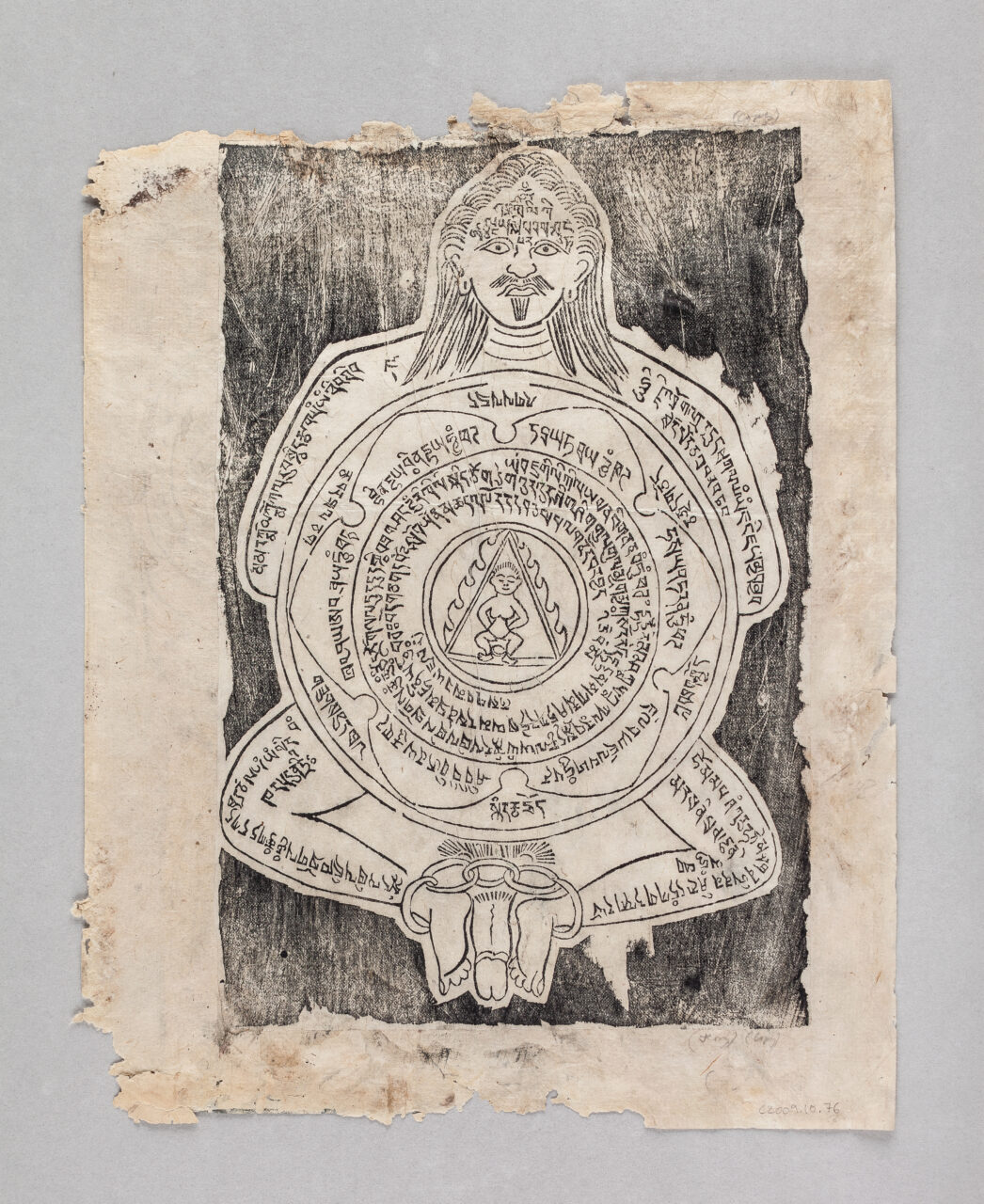

Woodblock Prints

Painted Woodblock Prints

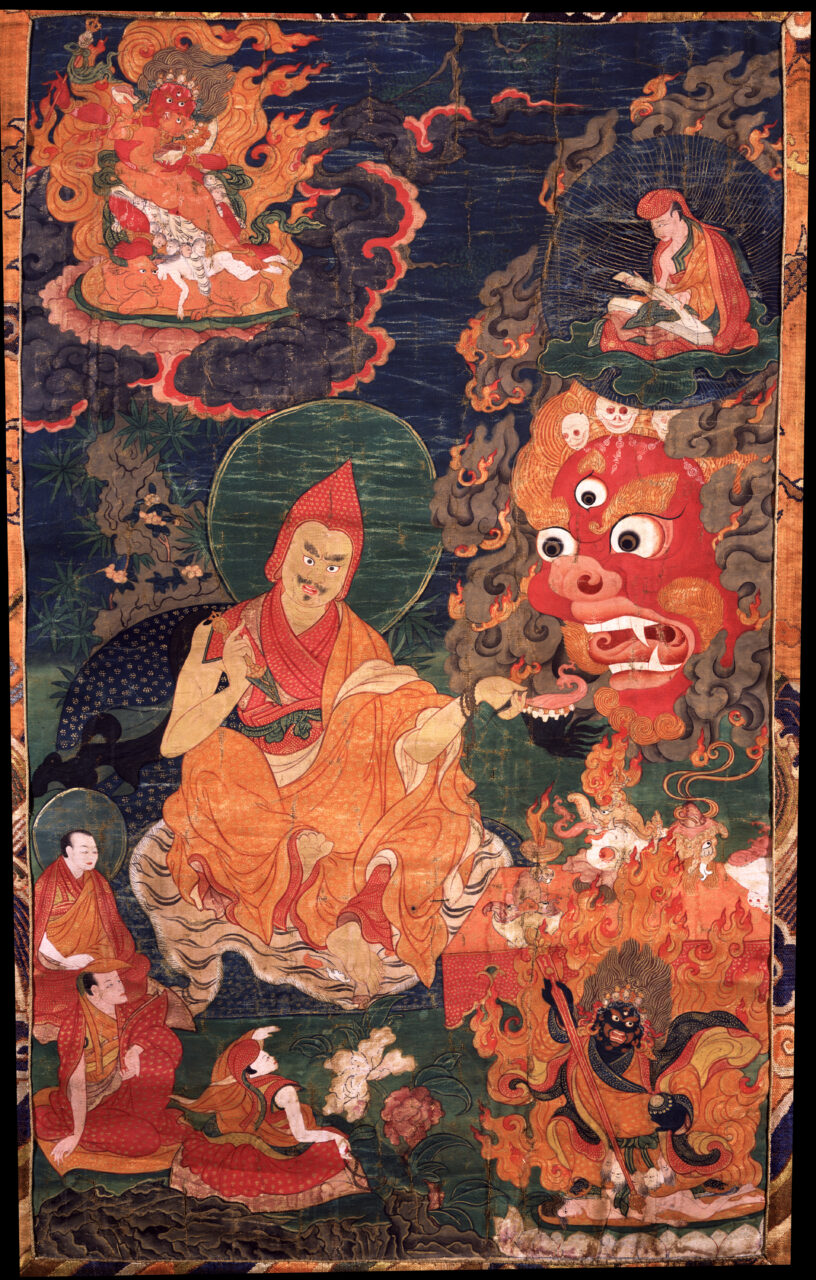

Woodblock Prints and Paintings Based on Them

Paintings and Textiles Based on Woodblock Prints

Video Resources Permalink

The Rubin Museum of Art, "Carving Wood Blocks at the Degé Printing House," YouTube, January 19, 2023, 14:00, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_m45p8aSNF0.

The Rubin Museum of Art, "Making Paper at the Dége Printing House," YouTube, January 19, 2023, 16:41, https://youtu.be/watch?v=He62uO7qGl4.

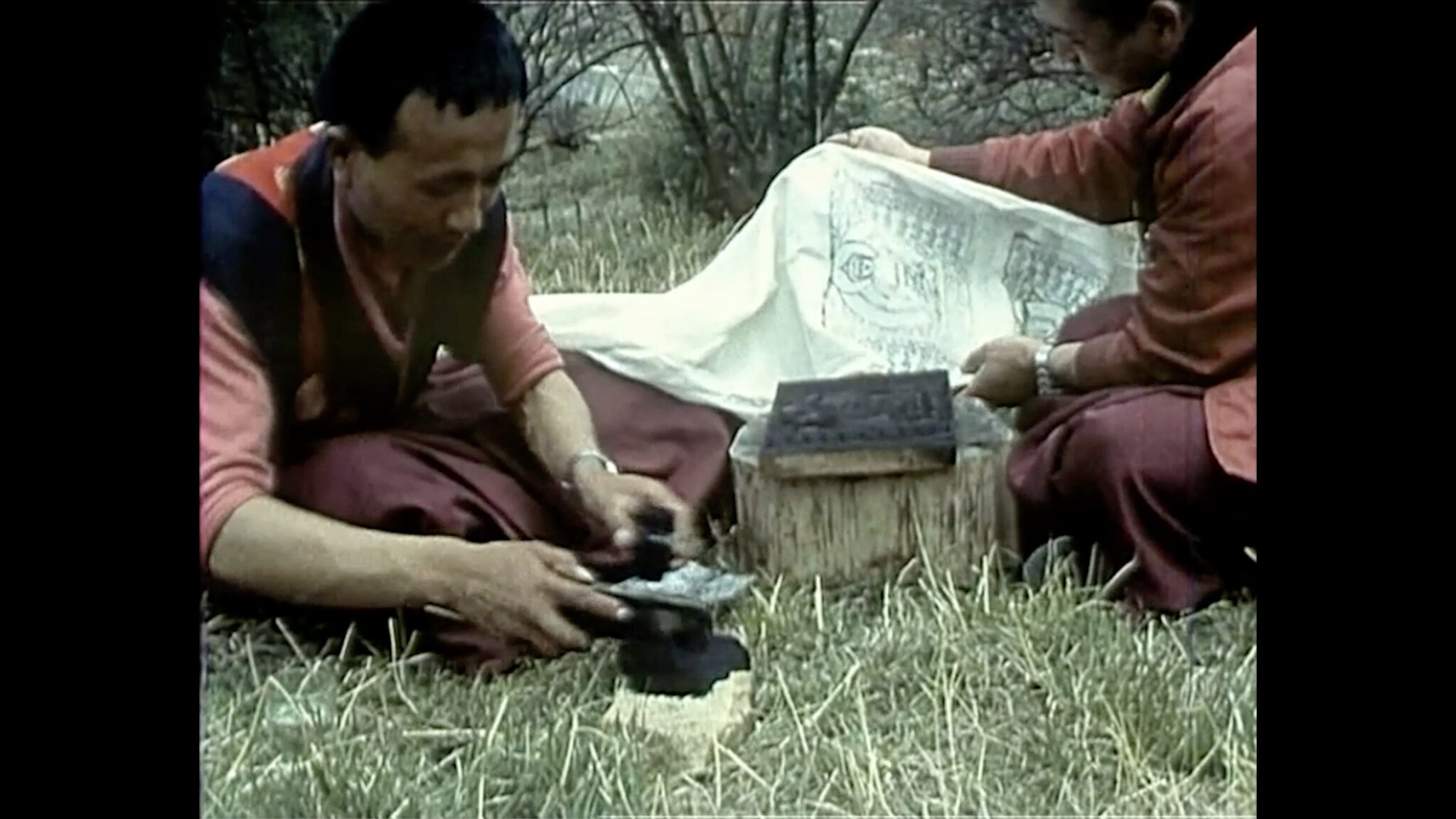

A segment from Art religieux du Bhoutan (Religious Arts of Bhutan), the film by Marie-Noëlle Frei-Pont. Filmed on an 8mm film, 1974 to 1982. With kind permission of Marie-Noëlle Frei-Pont & Society Switzerland-Bhutan. The Rubin Museum of Art, "Art religieux du Bhoutan (Religious Arts of Bhutan) - Prayer Flag Printing," YouTube, July 6, 2023, 3:55, https://youtu.be/cP3YnnGERKg.

Glossary Terms Permalink

appliqué

Appliqué is a technique of sewing patches of cloth, often silk or felt, onto a base to create a design or image. Used to make thangkas, carpets, and clothing, this technique allows for the creation of large-scale images, often hung from monastery walls or displayed on mountainsides as part of communal festivals and rituals. While the image may be designed by a Buddhist master, women are often involved in the creation of appliqués.

The Geluk are the most recent of the major “Later Diffusion” traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. Founded on the teachings of Tsongkhapa (1357–1419 CE) and his students, the Geluk are known for their emphasis on monastic discipline and the scholastic study of Mahayana philosophy, especially Madhyamaka. In the seventeenth century the Geluk supporting the Dalai Lamas became the largest and most powerful Buddhist tradition in both Tibet and Mongolia, where city-sized Geluk monasteries and their satellites proliferated widely. For long periods, Geluk monks effectively ruled both countries in dual-rulership or priest-patron political systems. A follower of the Geluk is called a Gelukpa.

The Kagyu are a major Later Diffusion tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. The Kagyu trace their lineages back to the Mahasiddhas, the great tantric masters of medieval India. The Kagyu are known for their yogic practices, as well as the teaching of Mahamudra, or the “Great Seal.” The Kagyu tradition includes many different branches, such as the Karma, Drukpa, Drigung, Tselpa, Pakmodru, and others. The most influential leaders of the Karma Kagyu are the Karmapas, a tulku lineage associated with that Kagyu branch. In Bhutan, the Drukpa Kagyu tradition serves as the state religion. A follower of the Kagyu is called a Kagyupa.

Manchus are an ethnic group originating in northeast Asia, roughly the area known as Manchuria. Historically known as Jurchens, in 1635 the ruler Hong Taiji (1592–1643) proclaimed the Qing Dynasty and officially changed the ethnic group’s name to “Manchu.” Qing emperors were said to be emanations of the bodhisattva Manjushri, and the name “Manchu” may relate to this. The Manchus formed the military aristocracy of this empire, which came to rule most of China, Mongolia, Tibet, and Eastern Central Asia until 1912. Many Manchus, including Qing emperors, had close political and spiritual relationships with Tibetan and Mongol lamas. Today the Manchus remain a major ethnic group within China, although very few people now speak the Manchu language.

Ming Dynasty

The Ming dynasty was a Chinese state that existed from 1368 to 1644 CE. The Ming founder, Zhu Yuanzhang (1328–1398), led an army that defeated the Yuan dynasty of the Mongol Empire and restored ethnic Chinese rule in China. Unlike the Mongols before them or the Qing dynasty after them the Ming never seriously attempted to rule the Tibetan regions, preferring instead to manage border affairs by granting titles and trading rights to friendly Tibetan monks and secular leaders. Nevertheless, several early Ming emperors had close personal relations with Tibetan lamas, and relations of trade and cultural interchange flourished between Chinese and Tibetan regions.

The Nyingma are a tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. The Nyingma trace their lineages back to the first introduction of Buddhism into the Himalayas in the time of the Tibetan Empire, most importantly to the legendary Indian yogin Padmasambhava. The Nyingma are known for their “treasure revealers” (Tib. terton), lamas who travel the Himalayas, revealing ritual texts, objects, and hidden lands thought to be concealed within the Tibetan landscape. The Nyingma are also famed for the Dzogchen teachings, a set of meditative practices focused on the bardo states, and the nature of the mind as pure, self-arising consciousness. Unlike other Buddhist traditions, many Nyingma practitioners are not celibate and can marry, raise families, and grant Vajrayana initiations and teachings to their children.

The Qing dynasty was a state that ruled in Eastern Asia from 1636 to 1912. Founded by the Manchus in 1644, the Qing armies crossed the Great Wall and began their conquest of the rest of the Chinese cultural region. By the 1750s the Qing empire had expanded to rule all of Mongolia, Tibet, and eastern Central Asia (including today’s Xinjiang), laying the groundwork for the modern state of China. The Qing governed Tibet and parts of Mongolia indirectly, in which the Manchu armies provided military support for local Buddhist governments like the Ganden Podrang. Tibetan and Mongol lamas were also extremely important in Qing court culture, and had close relationships with several Qing emperors.

Sakya is the name of a monastery and of a major tradition of Tibetan Buddhism that originated there during the Later Diffusion of Buddhism. Sakya Monastery was the seat of power during Sakya-Mongol rule in Tibet (1260–1350s), founded on the priest-patron relationship. Notable Sakya figures include Sakya Pandita (1182–1251), who played an instrumental role in establishing Tibetan relations with the Mongols; Drogon Chogyel Pakpa (1234-1280), who served as Qubilai Khan’s imperial preceptor and invented the Pakpa Script; and Buton (1290–1364), who compiled the Tibetan Canon. The Sakya are particularly known for their Lamdre teachings. In the 1350s, Pakmodru replaced the Sakya political prominence.

The Tanguts were an ethnic group in medieval East-Central Asia, who called themselves Minyak and spoke a language distantly related to Tibetan. Between 1038 and 1227 CE the Tanguts ruled a state in what is now the Chinese provinces of Ningxia, Gansu, and Qinghai. This state took the Chinese dynastic name of Xia, also called Xixia “Western Xia.” The Tangut-Xixia emperors were major patrons of Buddhism, inviting both Chinese and Tibetan monks to teach in the capital, and instituting major Buddhist translation and printing projects in three languages. The Tangut state was destroyed by the armies of Chinggis Khan, leading to their absorption into the Mongol Empire, where many Tanguts served as officials.

Tibetan Buddhist Canon

The Sanskrit Buddhist Canon was translated into Tibetan from the seventh century onward during the first and second diffusions. The Sakya-tradition scholar Buton Rinchen Drub (1290–1364) gave this mass of translations its final, codified form. The Tibetan canon is divided into two parts, which together usually take up hundreds of volumes:

- The Kangyur, “Translation of [the Buddha’s] Words,” contains texts believed to have been taught by the Buddha himself, including Sutras, Tantras, and the Vinaya.

- The Tengyur, “Translation of Teachings,” contains commentaries, scholastic works, philosophical studies, and other topics.

- The original Sanskrit canon was mostly lost with the decline of Buddhism in India, making the Tibetan and Chinese translations the only two surviving Mahayana canons.

The Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) is the branch of the Mongol Empire in Asia. In 1260 when Qubilai Khan declared himself Great Khan, his realm included Mongolian, Chinese, Tangut, and Tibetan regions. In 1271 emperor Qubilai Khan proclaimed the Yuan dynasty on a Chinese model, employing Tibetan and Tangut monks. Tibetan Buddhism played an important role in the state, establishing a political model that would be emulated by later dynasties, including the Chinese Ming and Manchu Qing dynasties. The Mongols were major patrons of Tibetan institutions, and many Mongols converted to Tibetan Buddhism, though their interest declined with the fall of the empire.