The Khalkha are one of the major historical subgroupings of the Mongols. Historically ruled by leaders descended from Chinggis Khan, the Khalkha inhabited a territory roughly the same as the country called Mongolia today. Other important Mongol groups after the fall of the Mongol Empire include the Chahars, who lived in what is today the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in China, the Oirat or Dzungars, who lived in Central Asia, and the Khoshut, who lived in the northern Tibetan Plateau.

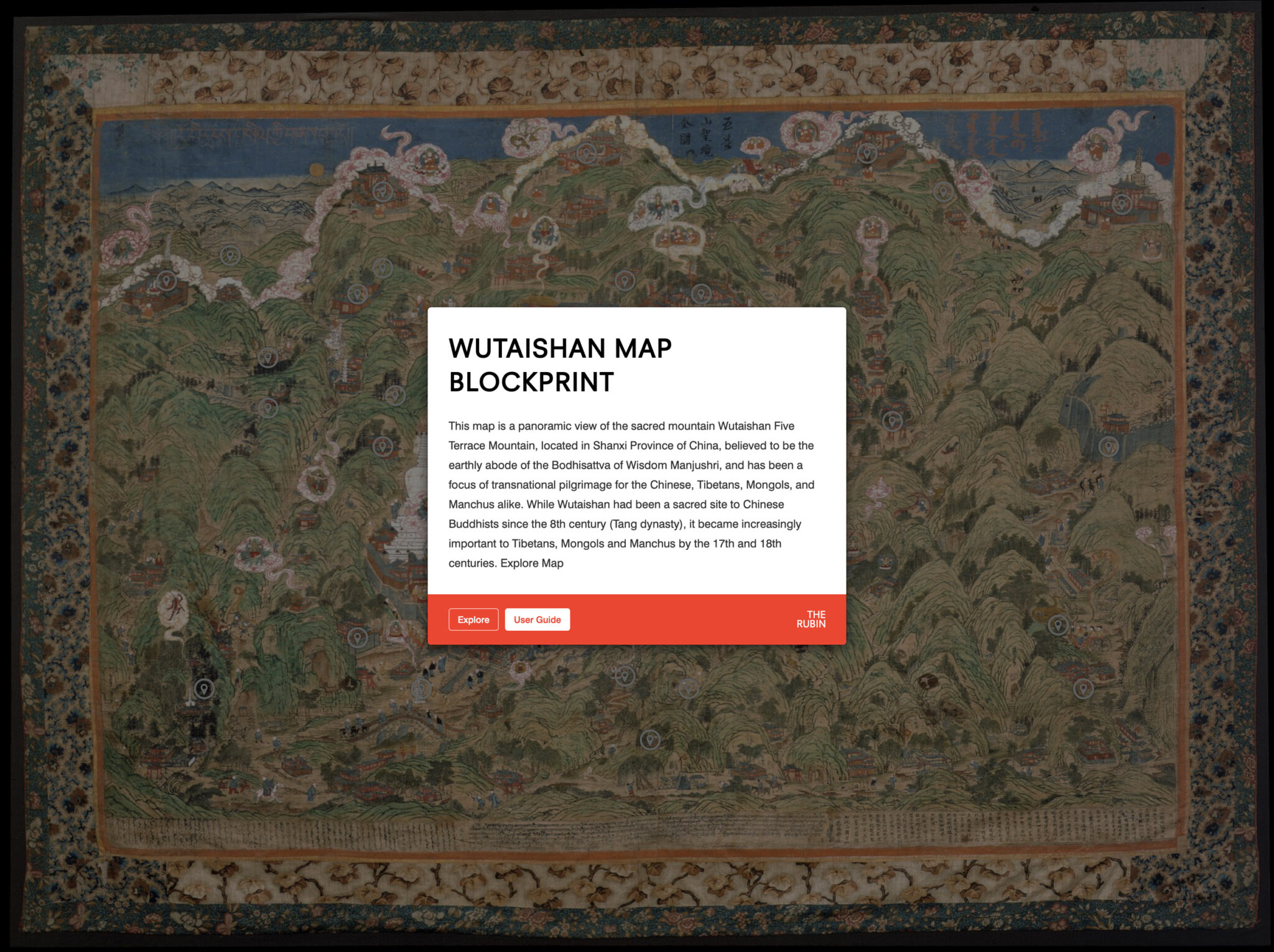

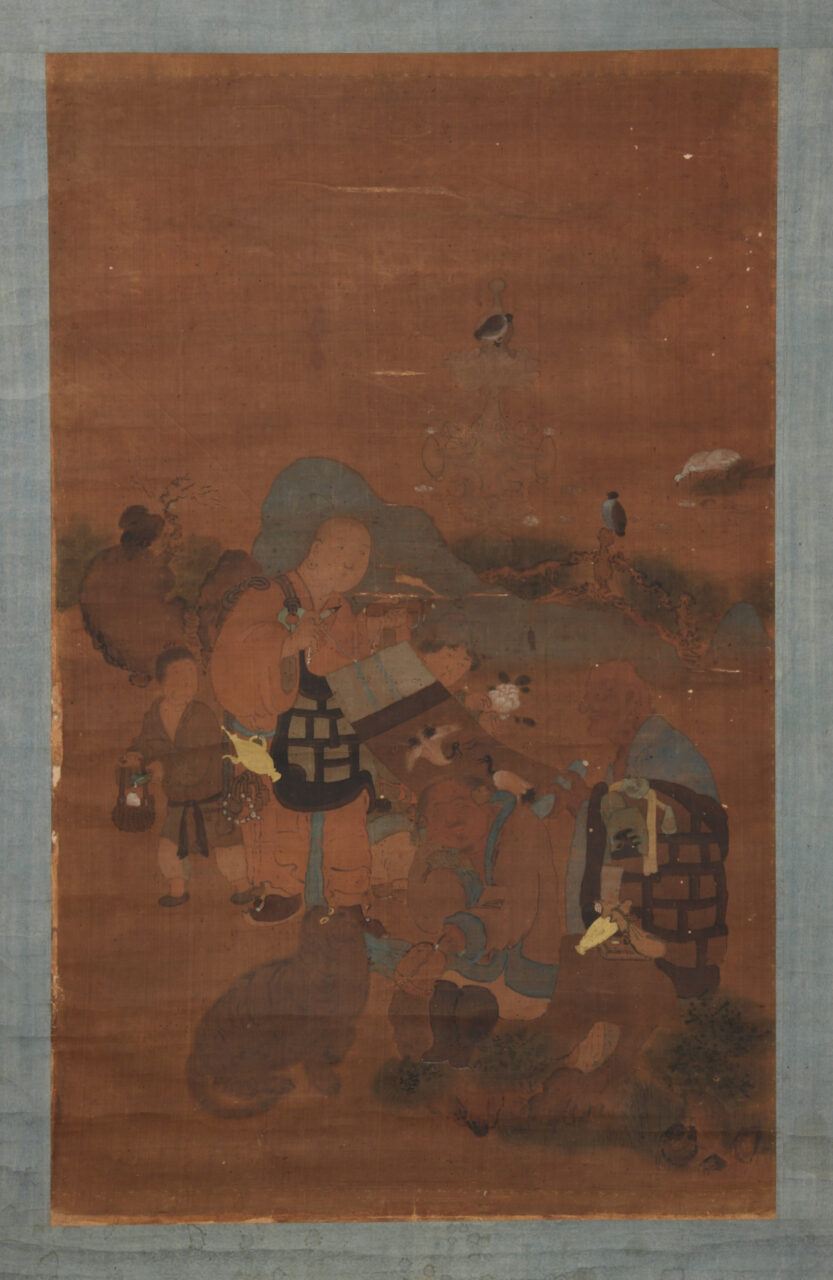

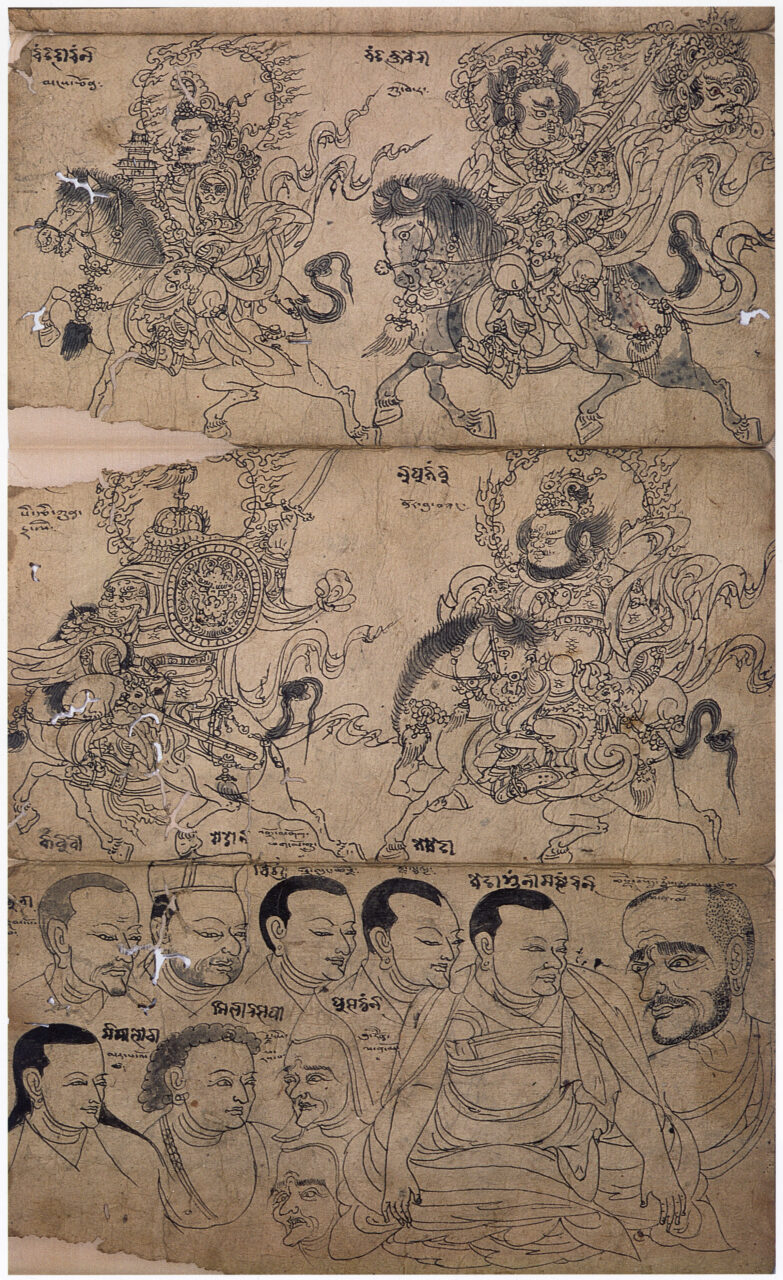

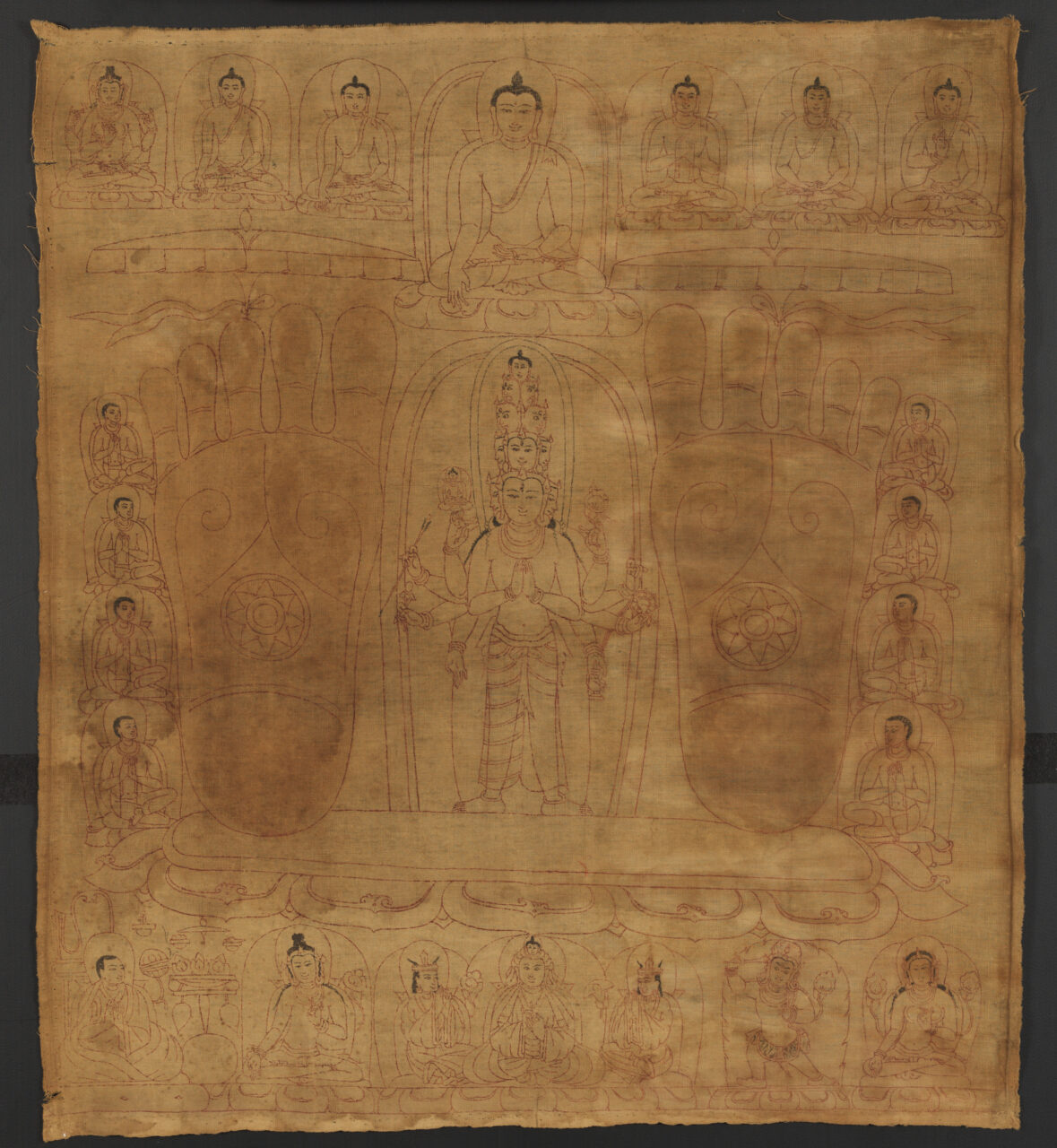

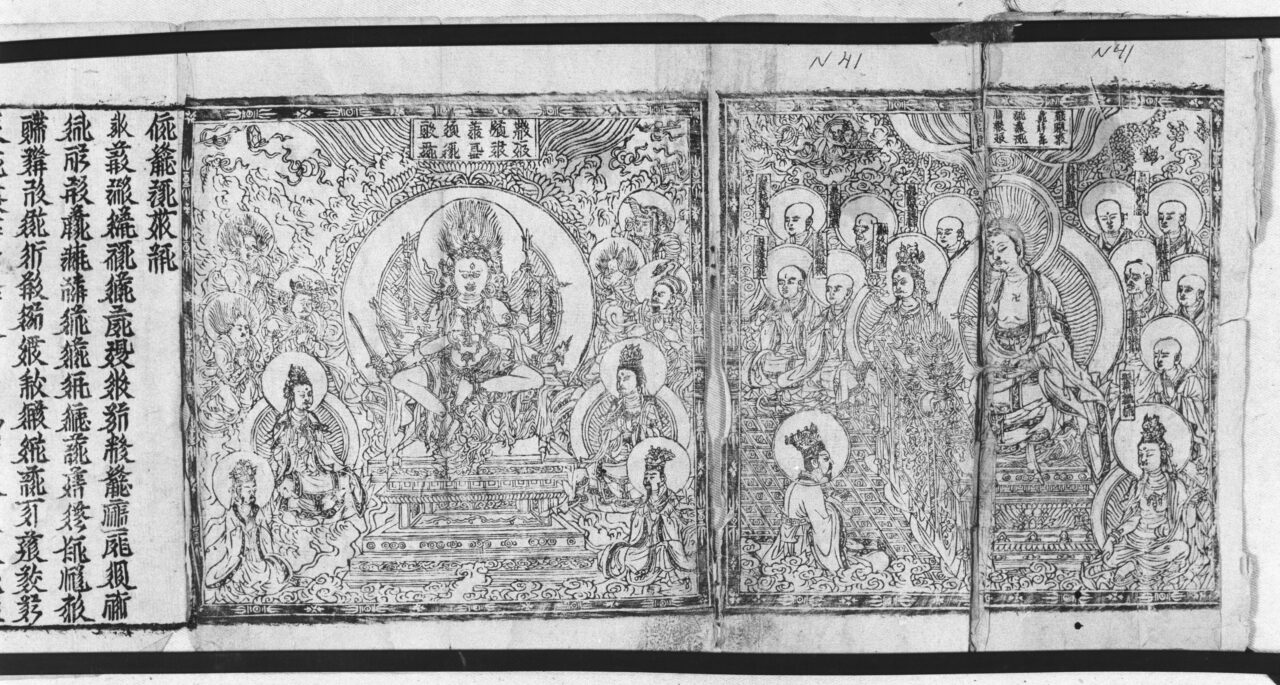

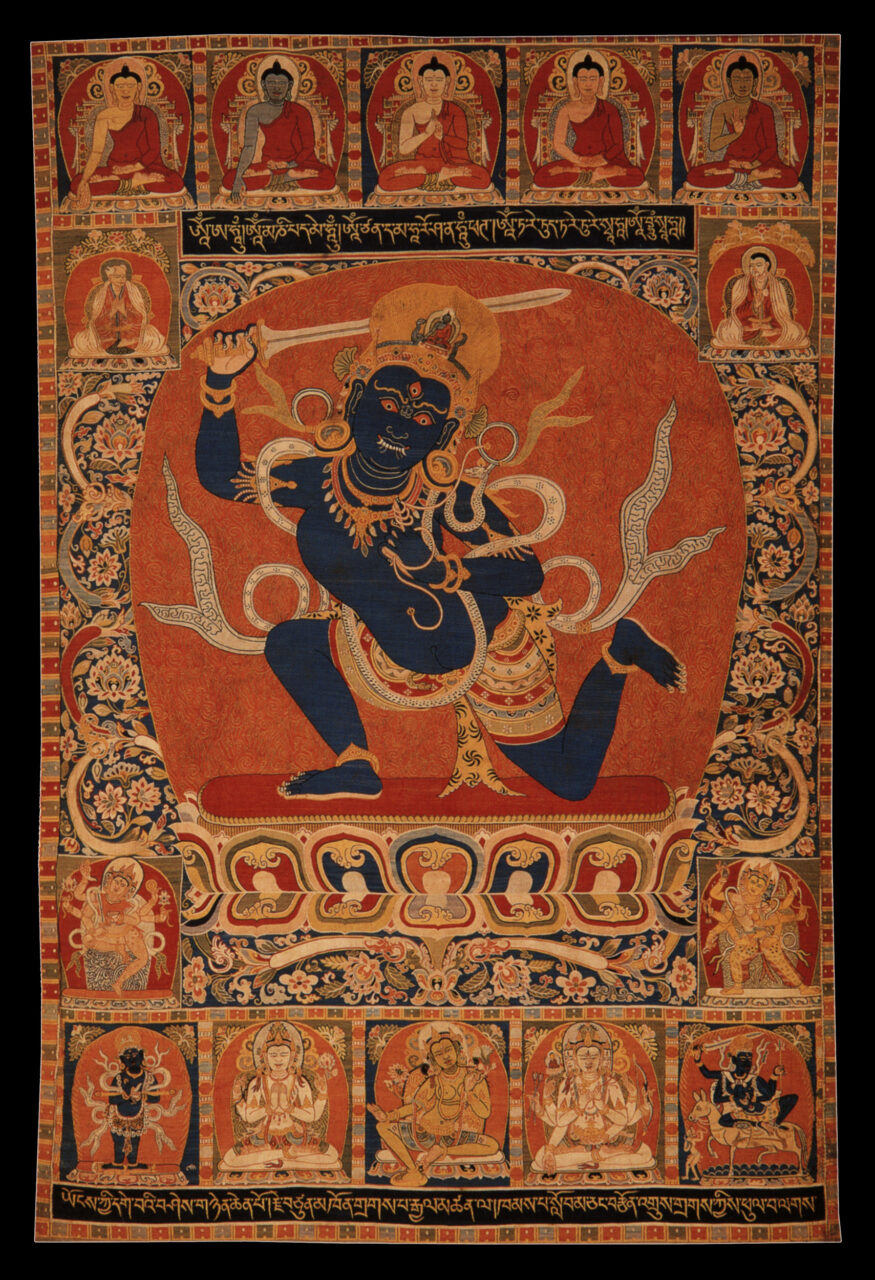

Manjushri is one of the most important bodhisattvas in Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Considered the embodiment of wisdom, Manjushri is often recognized by his attributes: a sword which cuts through ignorance and a book, the Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom) Sutra. Emanations of Manjushri can also be recognized by these same attributes. Another important Chinese iconographic tradition depicts a youthful Manjushri riding on a lion. This form is associated with Manjushri’s abode on earth, Mount Wutai in China, one of the few Buddhist sites in China visited by Tibetan and Mongol pilgrims among others from all over Asia. Manjushri was seen as the protector deity of China, and the Manchu emperors of the Qing Dynasty who claimed to be emanations of Manjushri emphasized/promoted this association.

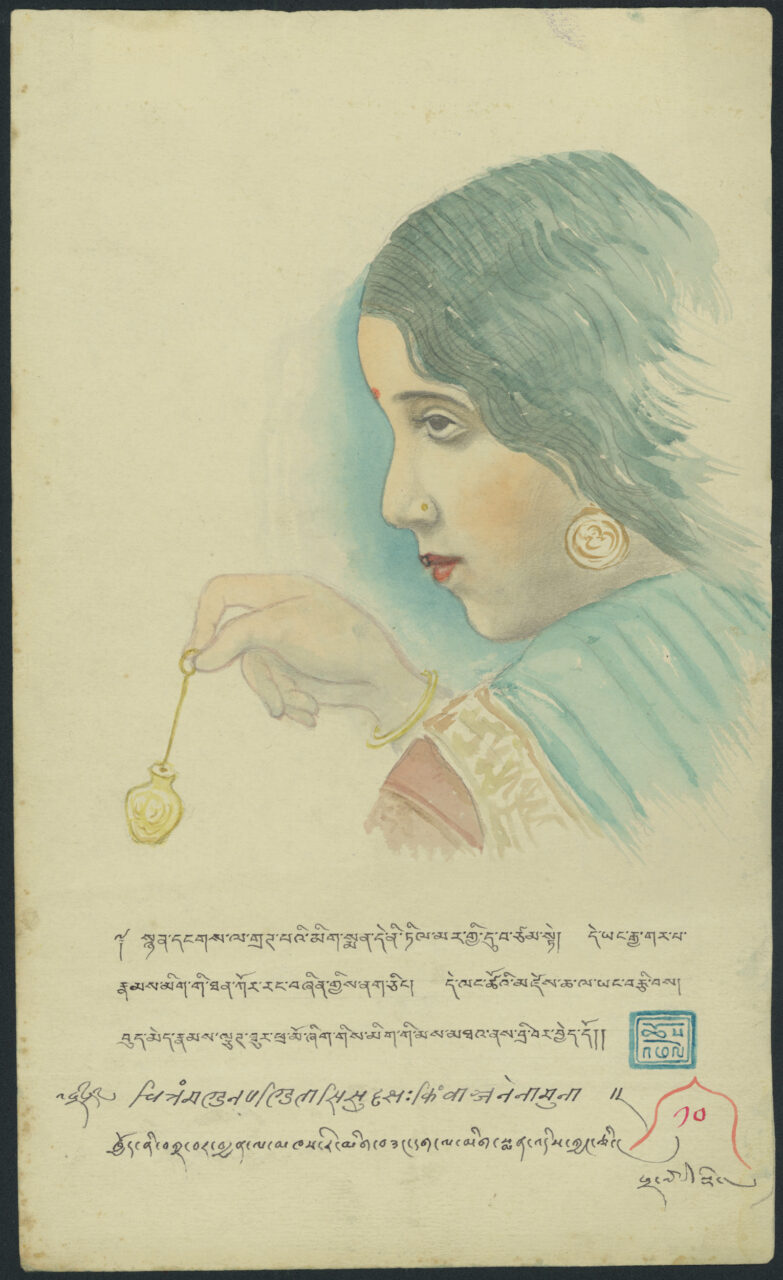

In Buddhism, merit is accumulated positive karma, or positive actions, that lead to positive results, such as better rebirths. Buddhists gain merit by reciting mantras, donating to monasteries and those in need, performing pilgrimages, commissioning artworks, reproducing and reciting Buddhist texts, and other deeds with good intentions. It is believed that merit can also be transferred to others through rituals performed to gain merit for deceased family members help them achieve a better rebirth. Merit making is an important motivation for positive ritual action, and is a prerequisite for success of religious and even secular activity.

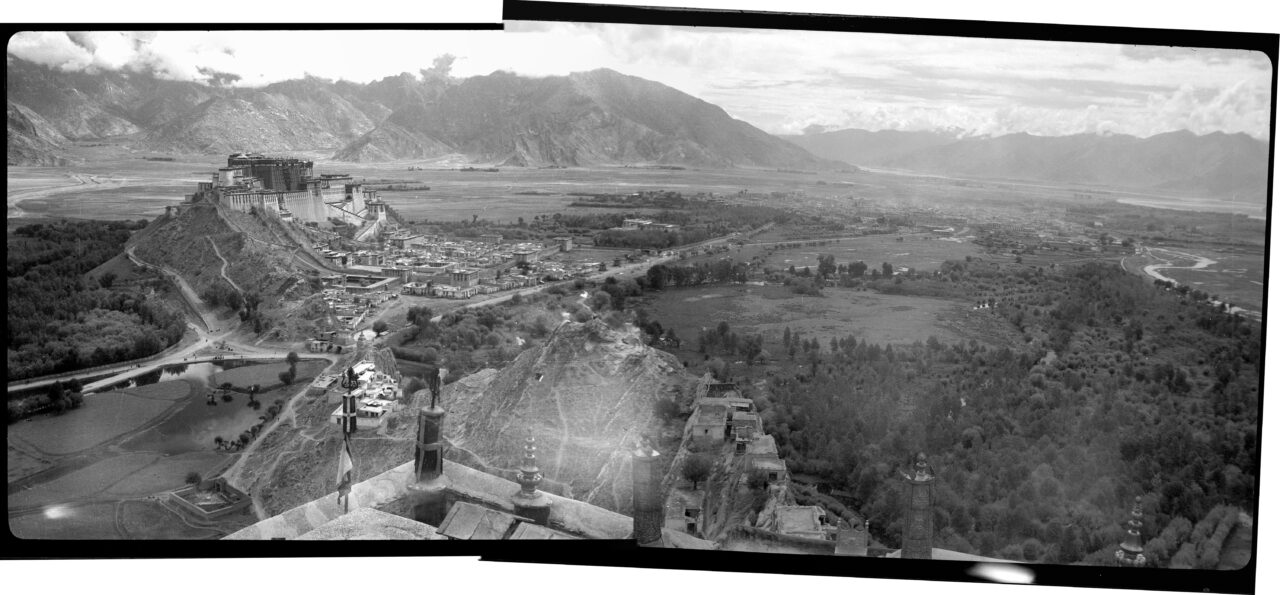

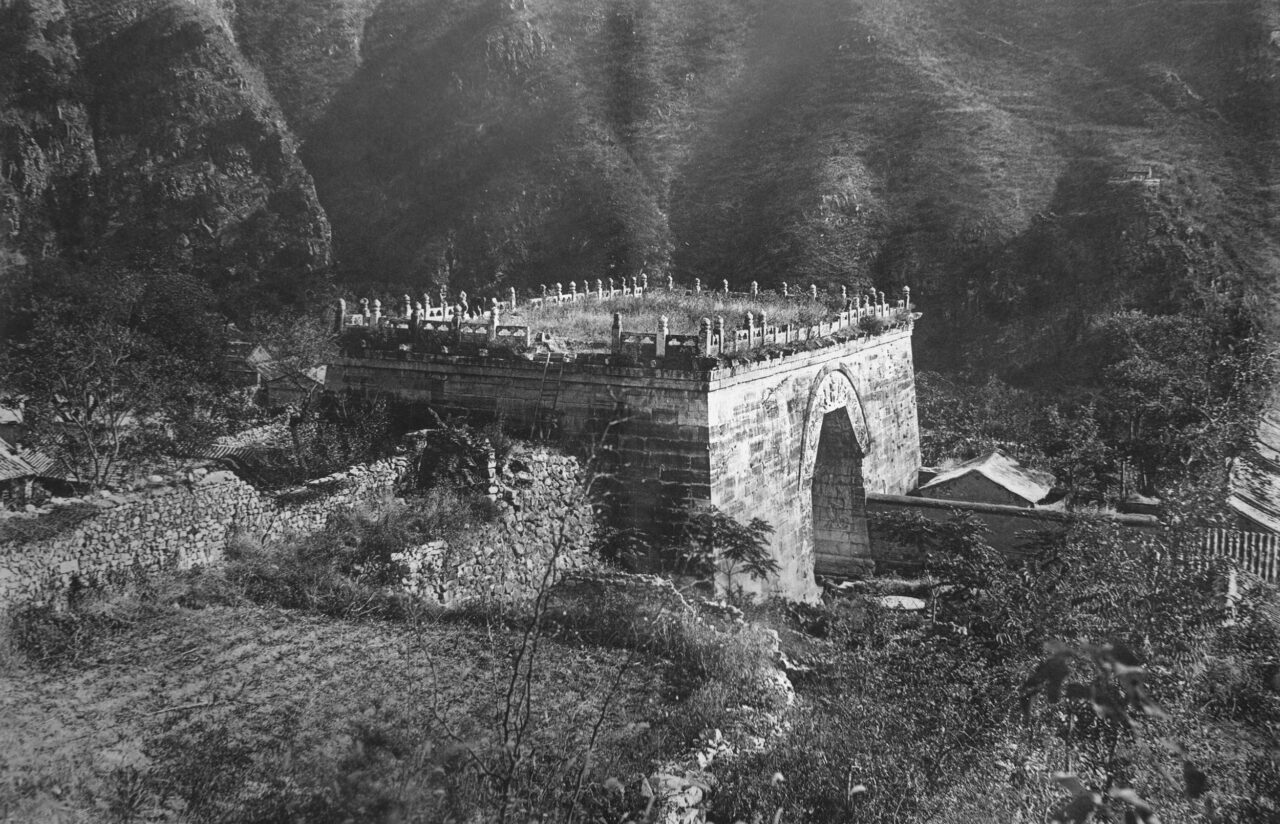

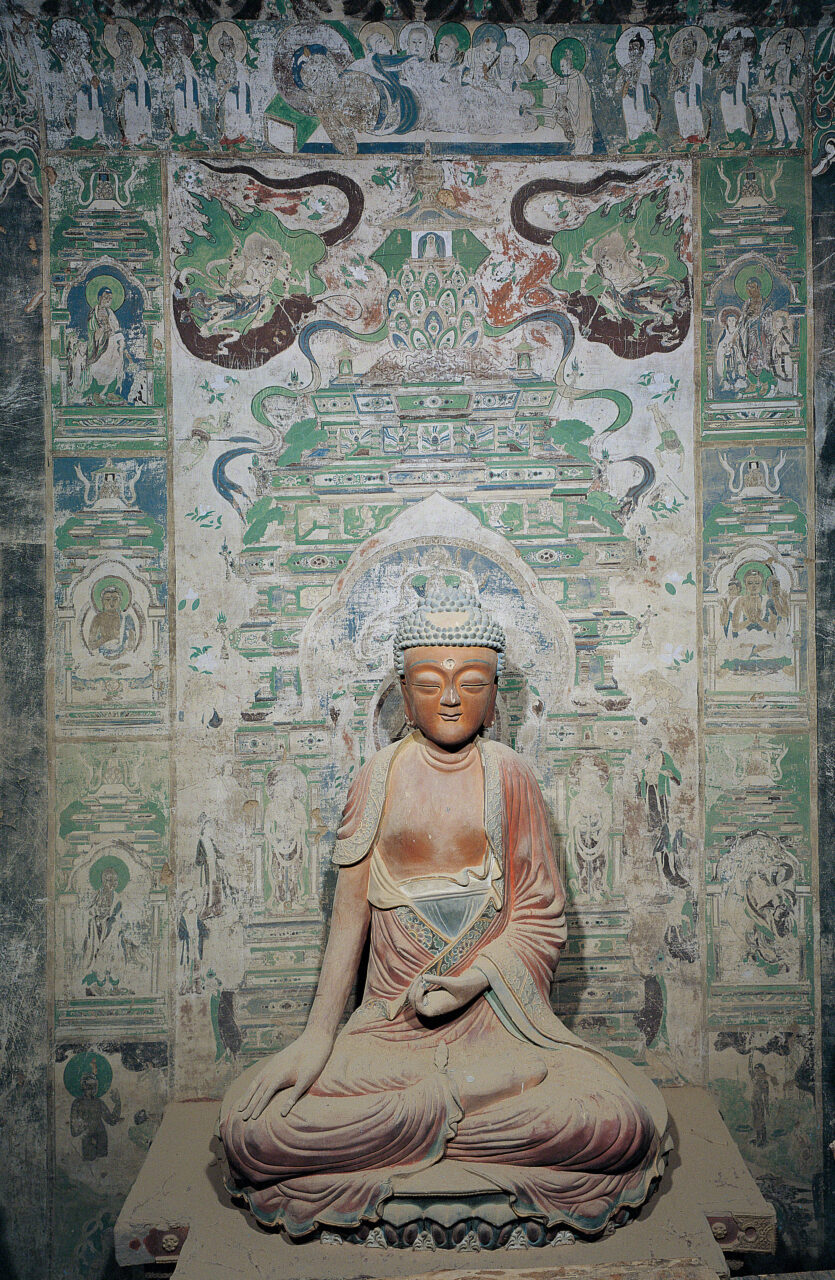

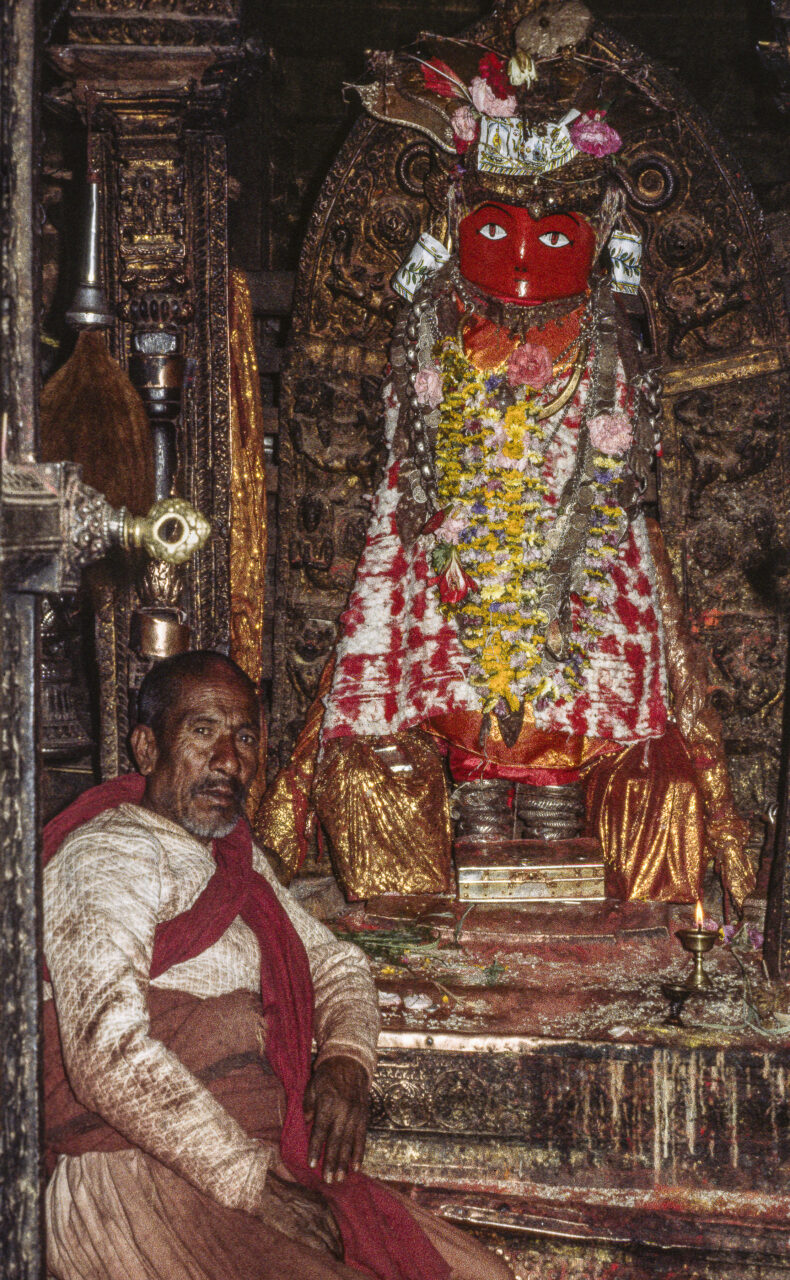

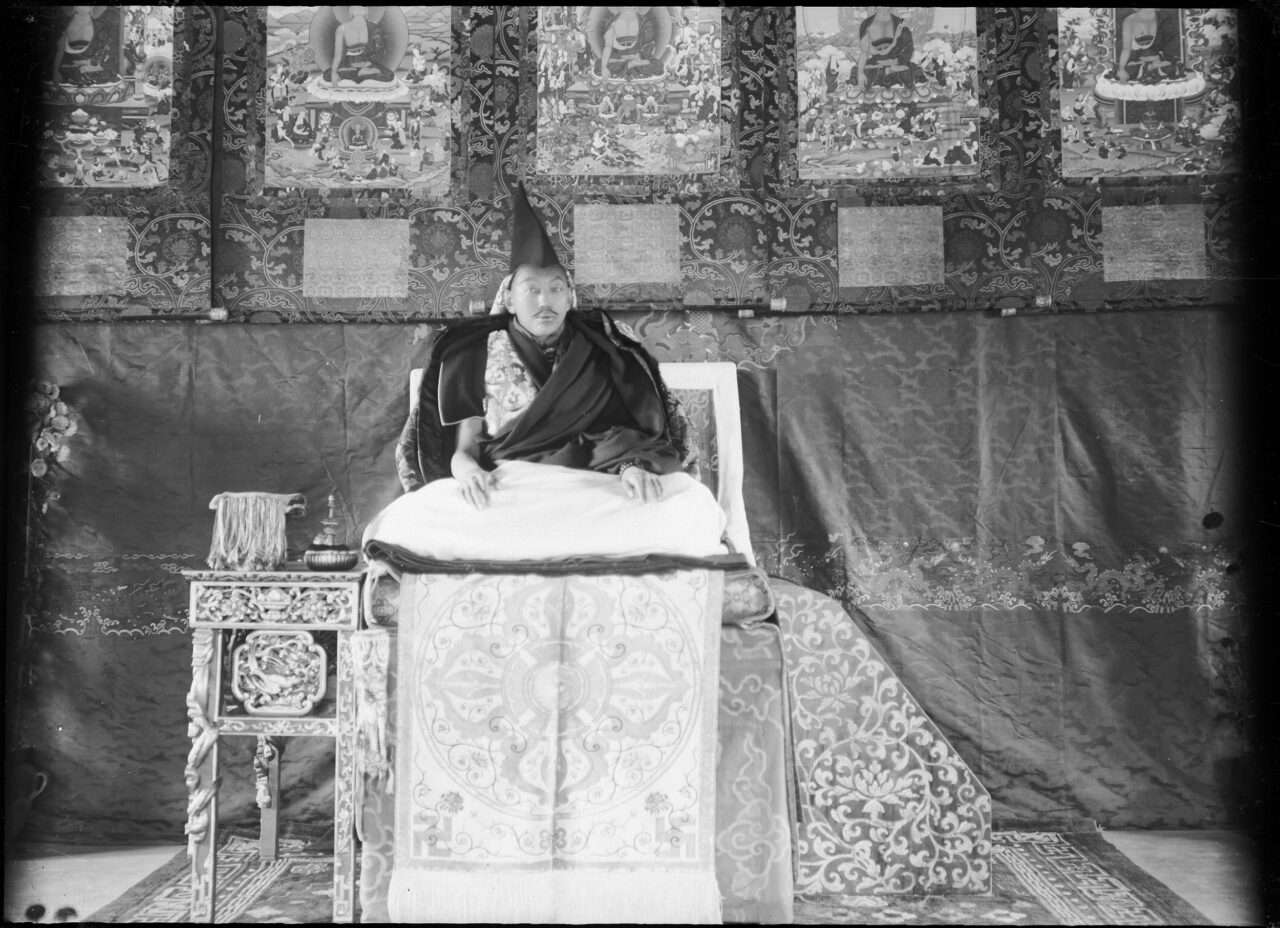

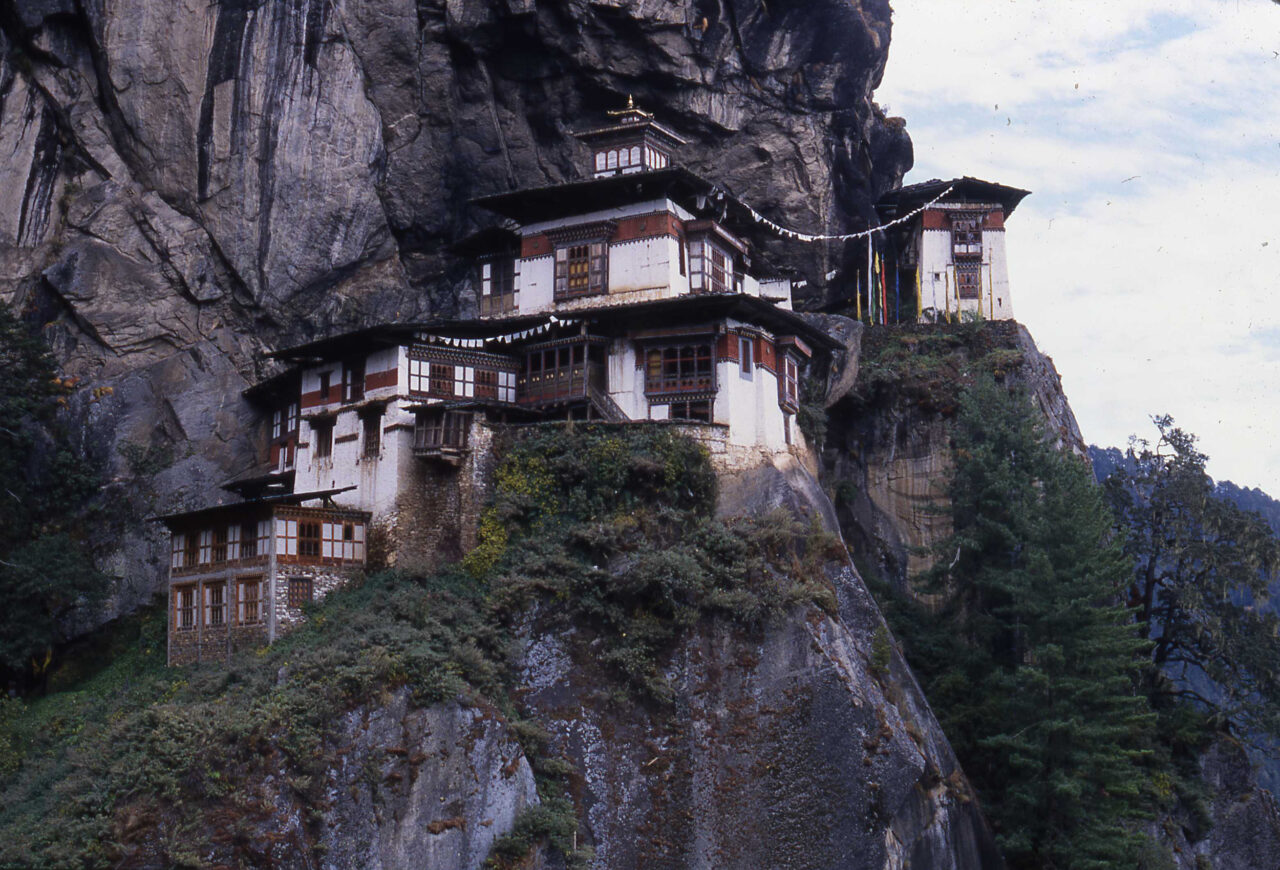

A monastery is a place where monks live, study, and perform ritual. It includes temples and other structures. Monasteries are central to Buddhism, and are also important in Bon, Hinduism, and Daoism. In Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian areas, some monasteries are enormous, wealthy, and powerful institutions, with branches of satellite monasteries forming networks across regions, often with thousands of monks, many decorated chapels, and huge holdings of land. Other monasteries, called hermitages, can be extremely simple, little more than a cave where hermits meditate. Generally, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery will have an assembly hall, several temples (Tib. lhakhang) for worship of specific deities, a protector chapel, as well as monks’ accommodations. A related institution in Newar Buddhism are the baha and bahi.

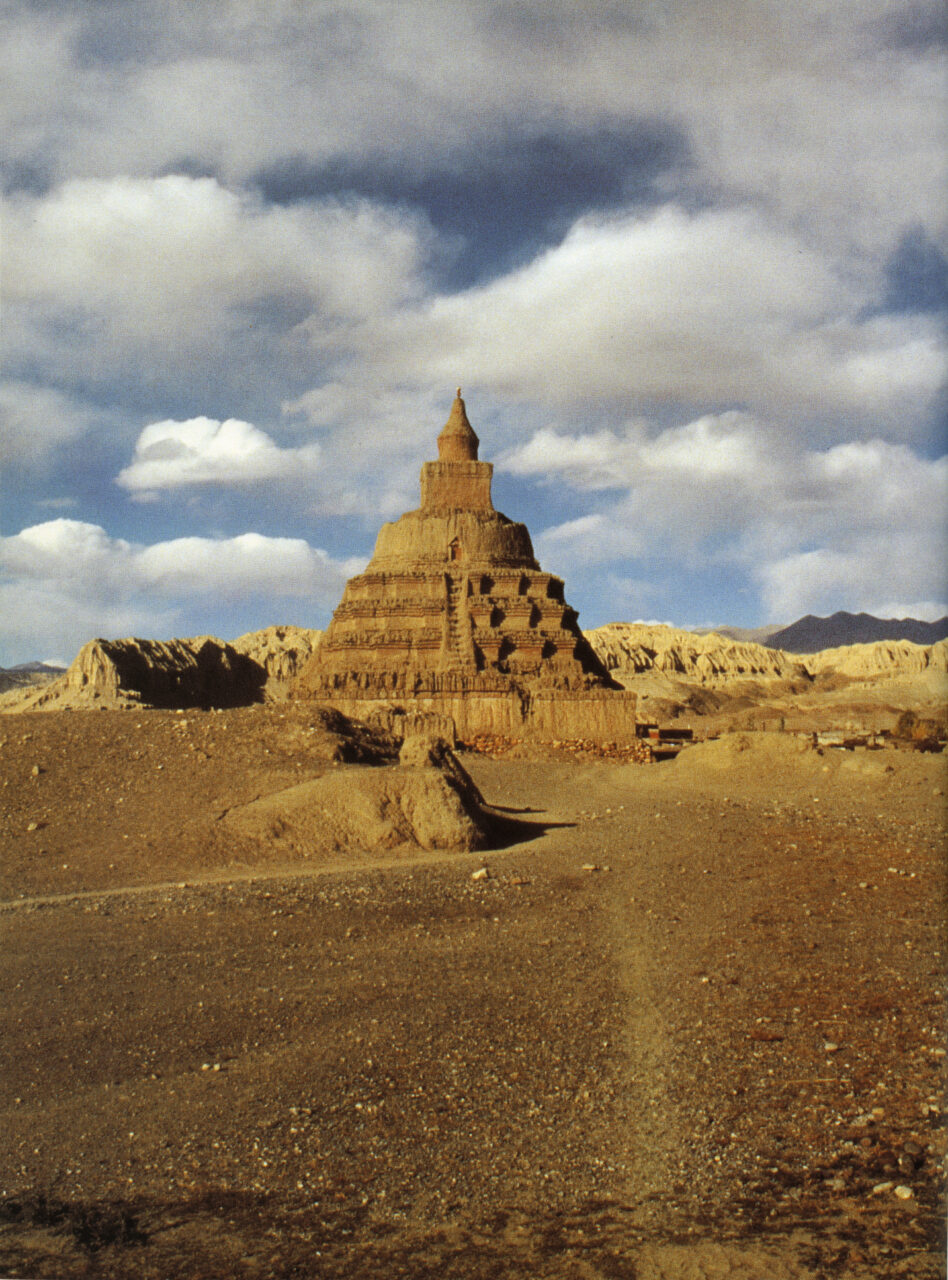

Stupas are monuments that initially contained cremated remains of Buddha Shakyamuni or important monks, his disciples, and subsequently other material and symbolic relics associated with the Buddha’s body, teaching, and enlightened mind. As representations of the Buddha’s presence in the world, stupas with their contents—texts, relics, tsatsas—continue to be important objects of Buddhist worship in their diverse forms of domed structures, multistoried pagodas, and portable sculptures. The original form of stupas was an earthen dome-shaped mound containing the remains in reliquary vessels or urns deposited within the innermost core. The dome would often be successively enlarged and surrounded by a path for a walk around in a clockwise direction and veneration (circumambulation)

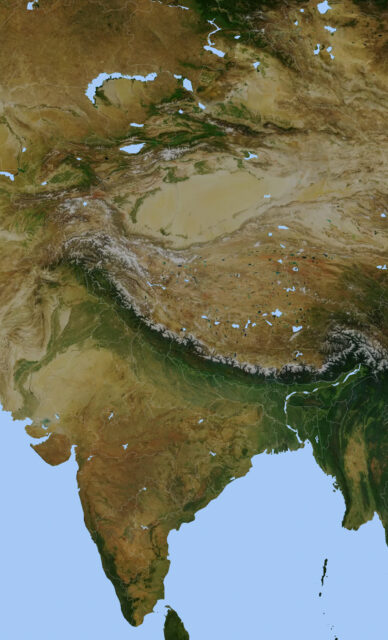

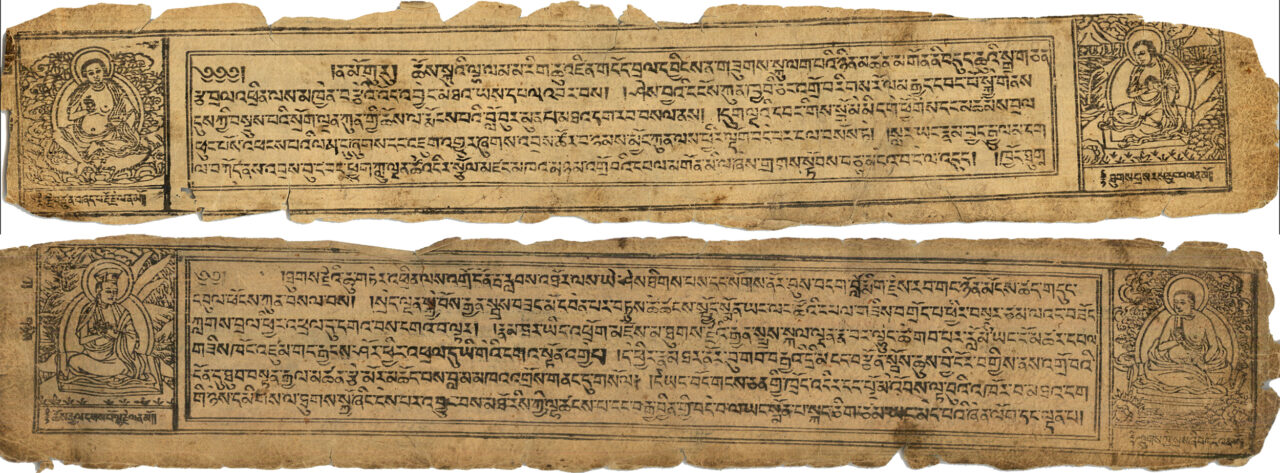

Historically, Tibetan Buddhism refers to those Buddhist traditions that use Tibetan as a ritual language. It is practiced in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, Ladakh, and among certain groups in Nepal, China, and Russia and has an international following. Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in two waves, first when rulers of the Tibetan Empire (seventh to ninth centuries CE), embraced the Buddhist faith as their state religion, and during the second diffusion (late tenth through thirteenth centuries), when monks and translators brought in Buddhist culture from India, Nepal, and Central Asia. As a result, the entire Buddhist canon was translated into Tibetan, and monasteries grew to become centers of intellectual, cultural, and political power. From the end of the twelfth century, Tibetans were exporting their own Buddhist traditions abroad. Tibetan Buddhism integrates Mahayana teachings with the esoteric practices of Vajrayana, and includes those developed in Tibet, such as Dzogchen, as well as indigenous Tibetan religious practices focused on local gods. Historically major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism are Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Geluk.