Artists Permalink

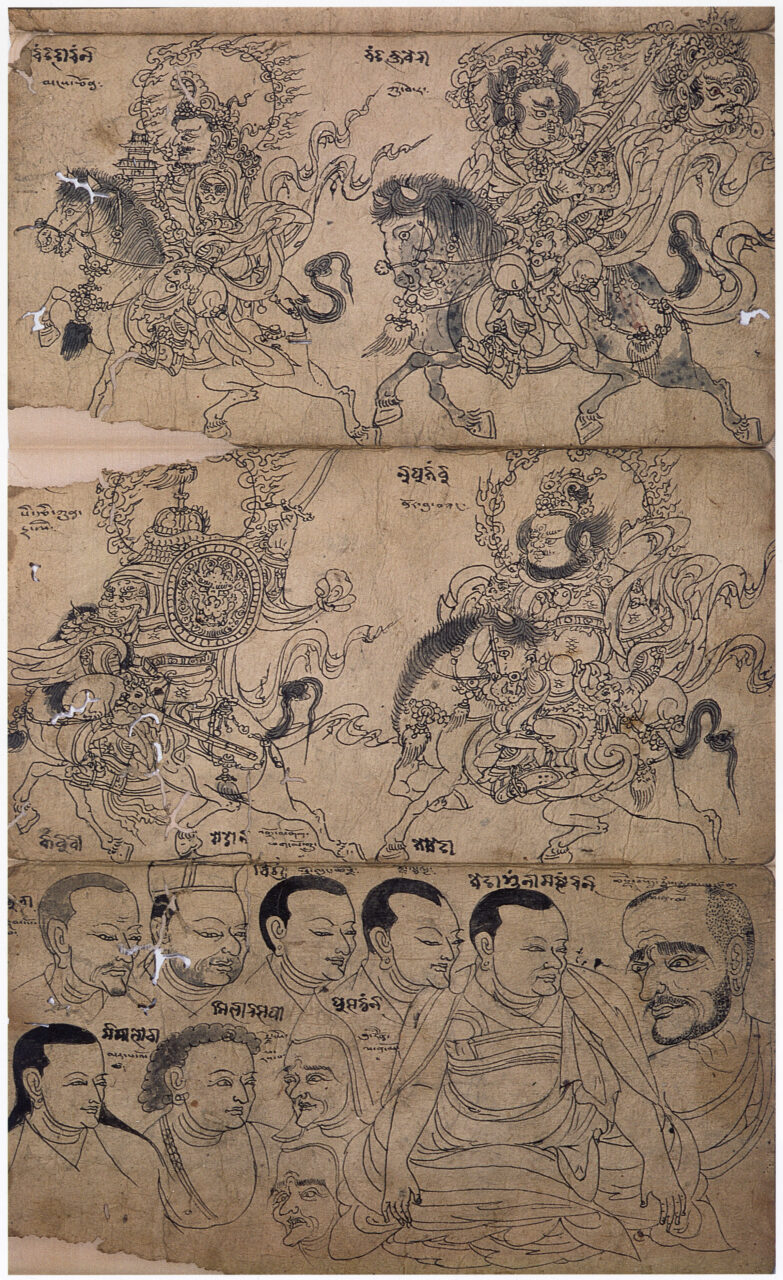

Historically, artists in the Tibetan tradition have been mostly laymen who passed down artistic practices within families. Groups of artists in workshops run by one or more master artists also produced many artworks. These master artists would design works or compose initial sketches, while apprentices and artisans assisted with specific techniques or specialized aspects of artistic production, such as gold work or ornamentation. This hierarchy and collaboration of artisans allowed workshops to produce large-scale works with highly polished results. From the seventeenth century on, artists in central Tibet were organized into guilds that required artisans to undertake specific tasks for government projects for part of the year. This entailed the systemization of artistic practices among them, such as rules of figural proportions ().

While the names of artists are sometimes preserved on artworks or in historical sources, most artworks do not bear the names of their creators, and typically little is known about them. This does not mean that artists were historically anonymous—in monastic collections that remain intact, the great artists’ names are remembered and their works recognized.

Because much of this art has been lost or removed from its original context, often through violent social upheavals, this local knowledge is lost. In a few cases, details about famous artists who founded influential painting or sculptural traditions, or were in the employ of courts, are recorded in historical sources.

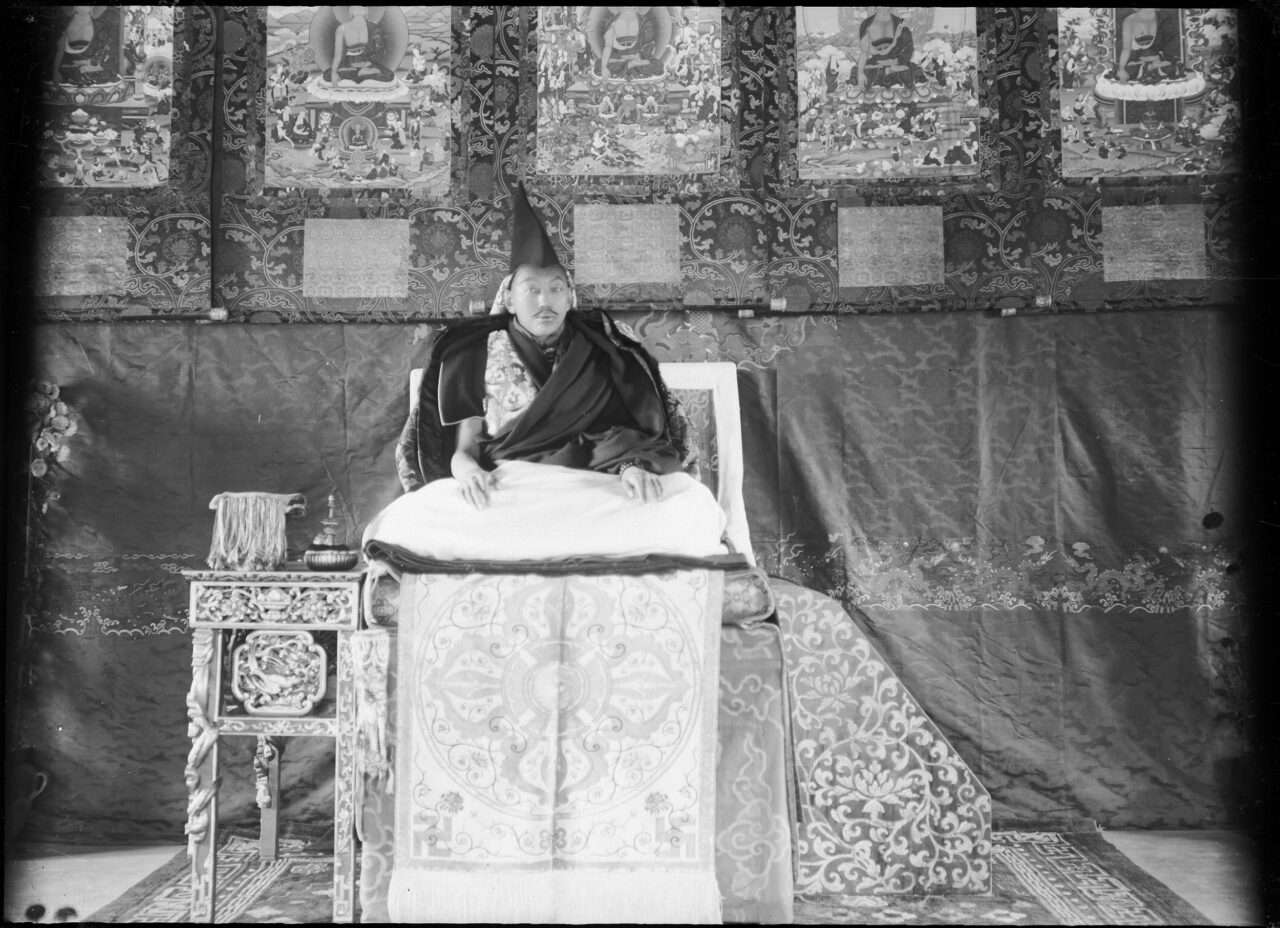

Images are important to religious practices, so the arts are included in Tibetan monastic training as one of the minor fields of knowledge. Some religious figures who showed an interest and aptitude for image making became famous for their art. Their lives were often documented, including the stories of their artistic careers, because of their significance in religious lineages. Due in part to their religious status, their works became models for later , inspiring specific artistic movements. Some of these talented religious masters also used their knowledge to become great patrons of the arts (fig. 1).

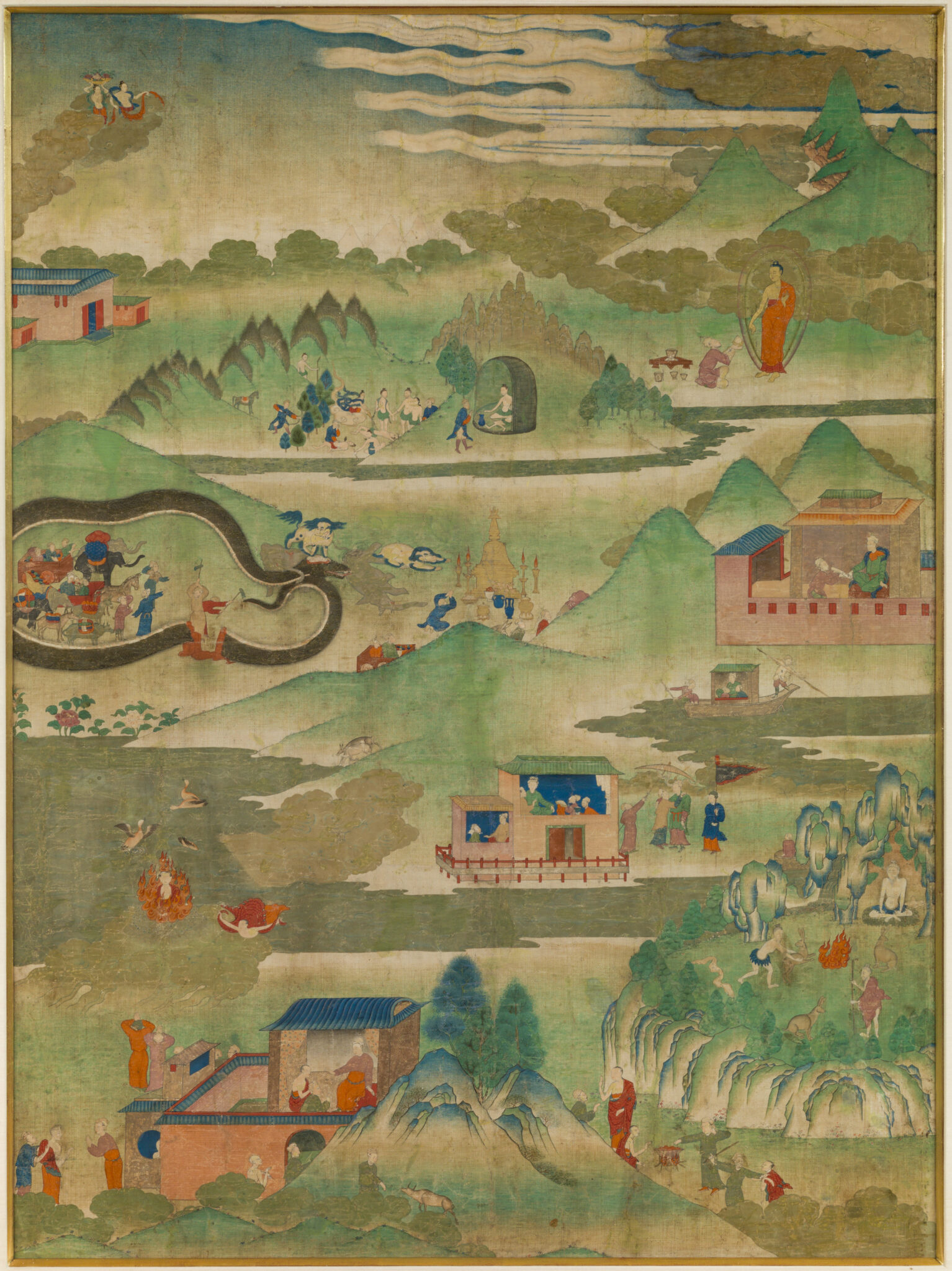

Situ Panchen as Patron of The Wish-Granting Vine Series of One Hundred and Eight Morality Tales, twenty-third painting after Situ’s set; Kham region, eastern Tibet; 19th century; pigments on cotton; dimensions unknown; Pelpung Monastery Collection; photograph courtesy of Sherab-ling Monastery

In Nepal, -related traditions of metalworking, wood carving, stone carving, and painting established family lineages of artistic practice. The caste system was codified during the religious and cultural reforms of the Malla Period (1200–1769). Thereafter, one’s caste and clan titles governed traditional occupations, including artistic practice. This arrangement established family lineages of production that distributed the creation of art objects across caste groups. More importantly, it ensured each caste group had a vital role in the construction, maintenance, and restoration of temples and monasteries in the . While contemporary artistic practice has seen a break in the strict caste and gender categories, family workshops and ateliers producing traditional religious art are still rooted in the legacy of caste-related artistic inheritance.

Works by Named Artists Permalink

These are the nineteen objects in Project Himalayan Art with named artists

Works by Artists Who Founded Artistic Traditions Permalink

Patrons Permalink

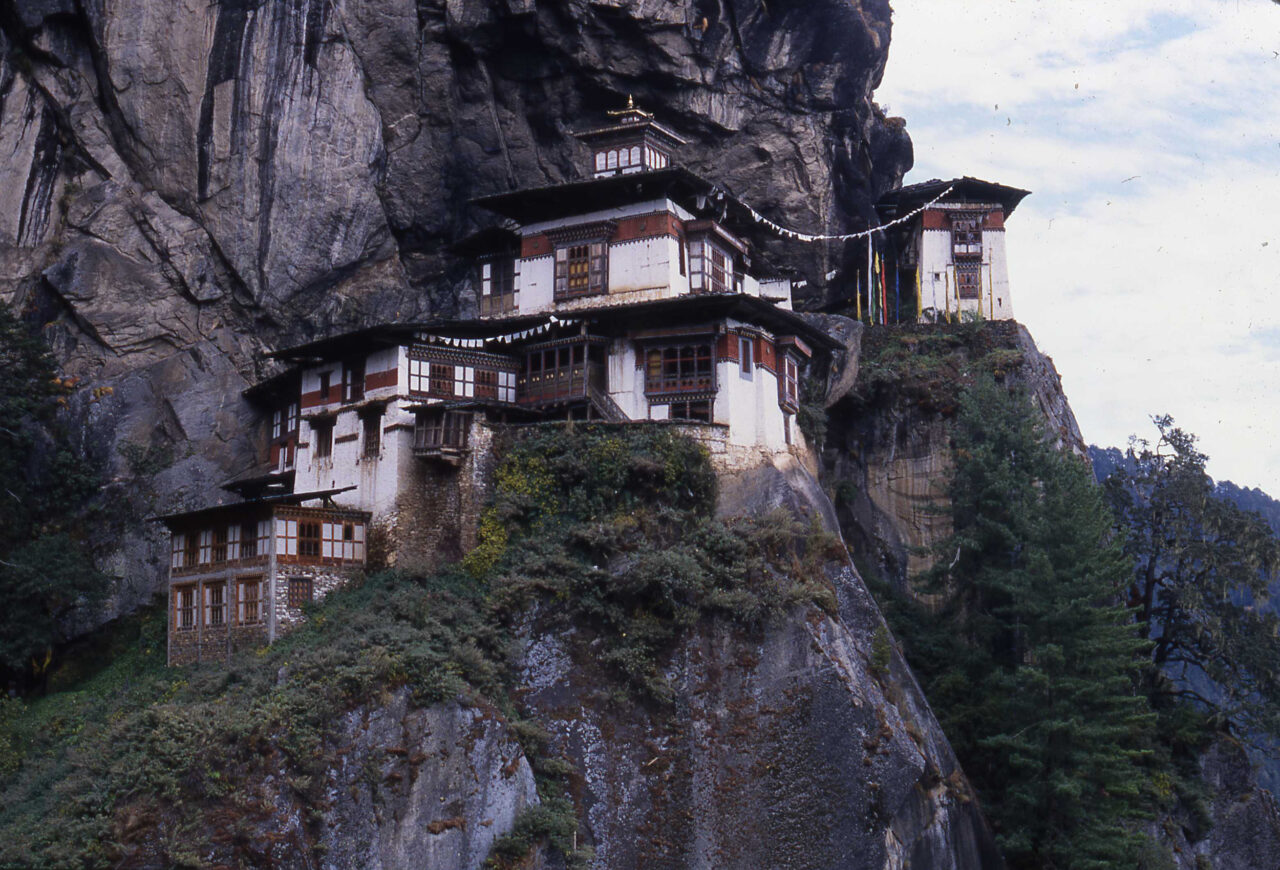

with vast resources were important sources of artistic and their own workshops. More often they employed traveling artists from other regions, like the of the Kathmandu Valley, who were renowned painters (fig. 2), wood carvers, and statue casters. Sometimes inscriptions on objects, biographies, or local histories record the names of abbots and other prominent members of the religious community who commissioned artworks (fig. 3). Some religious masters who took special interest in image making were closely involved in their art commissions, directing the artists and in some cases even designing compositions.

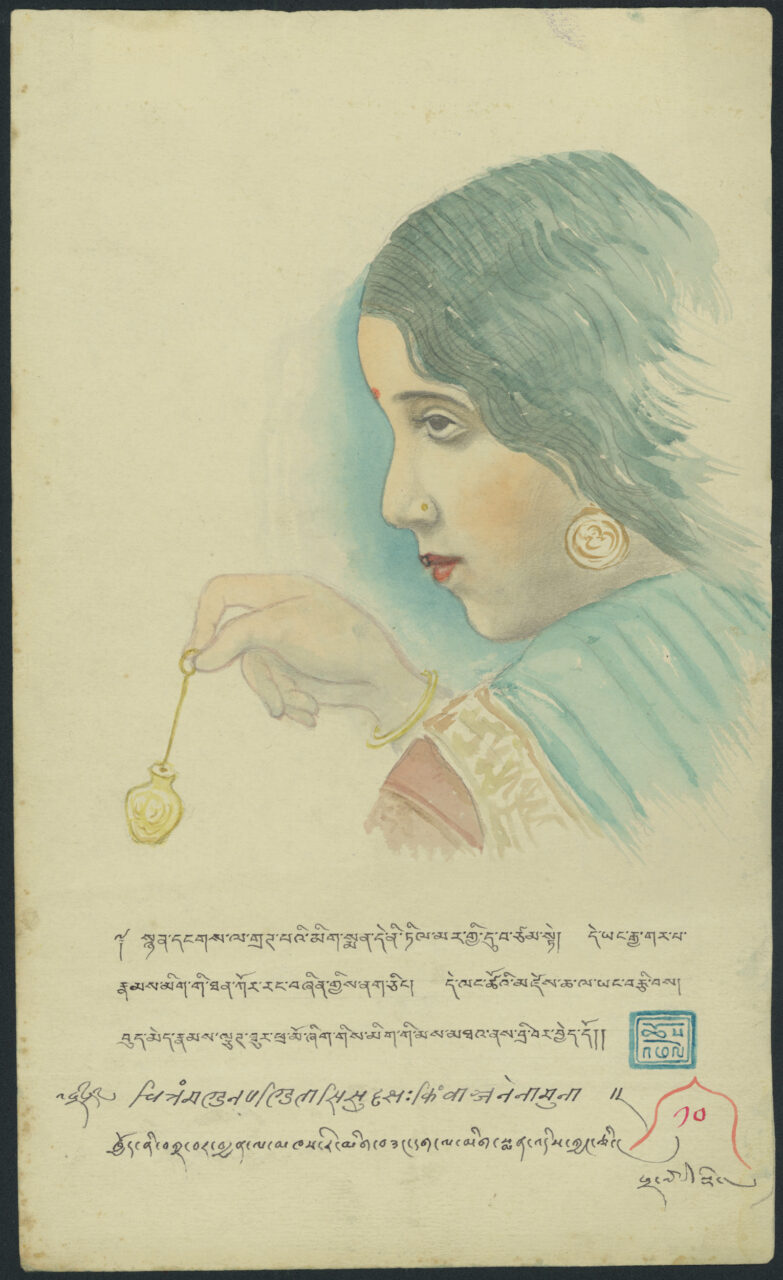

Everyday people commission more modest paintings and sculptures for personal reasons, including individual devotional practice or to honor the passing of a loved one (fig. 4), often on the advice of a religious teacher. Patrons also use art to commemorate their sponsorship of rituals (pujas), festivals, or celebrations, serving as a historical record of these activities.

Chakrasamvara Mandala; Nepal; ca. 1100; mineral and organic colorants on cotton; Image: 26 1/2 × 19 3/4 in. (67.3 × 50.2 cm); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Rogers Fund, 1995; 1995.233; CC0 – Creative Common (CC0 1.0)

Four Mandalas of the Vajravali Cycle; Ewam Choden Monastery, Tsang Province, Central Tibet; 1429-1456; Pigments on cloth; 36 × 30 in. (estimated); Rubin Museum of Art; C2007.6.1 (HAR 81826)

Sitatapatra; Tibet; dated 1864; Pigments on cloth; 27 3/4 × 20 1/2 in. (estimated); Rubin Museum of Art, Gift of the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation; F1996.18.1

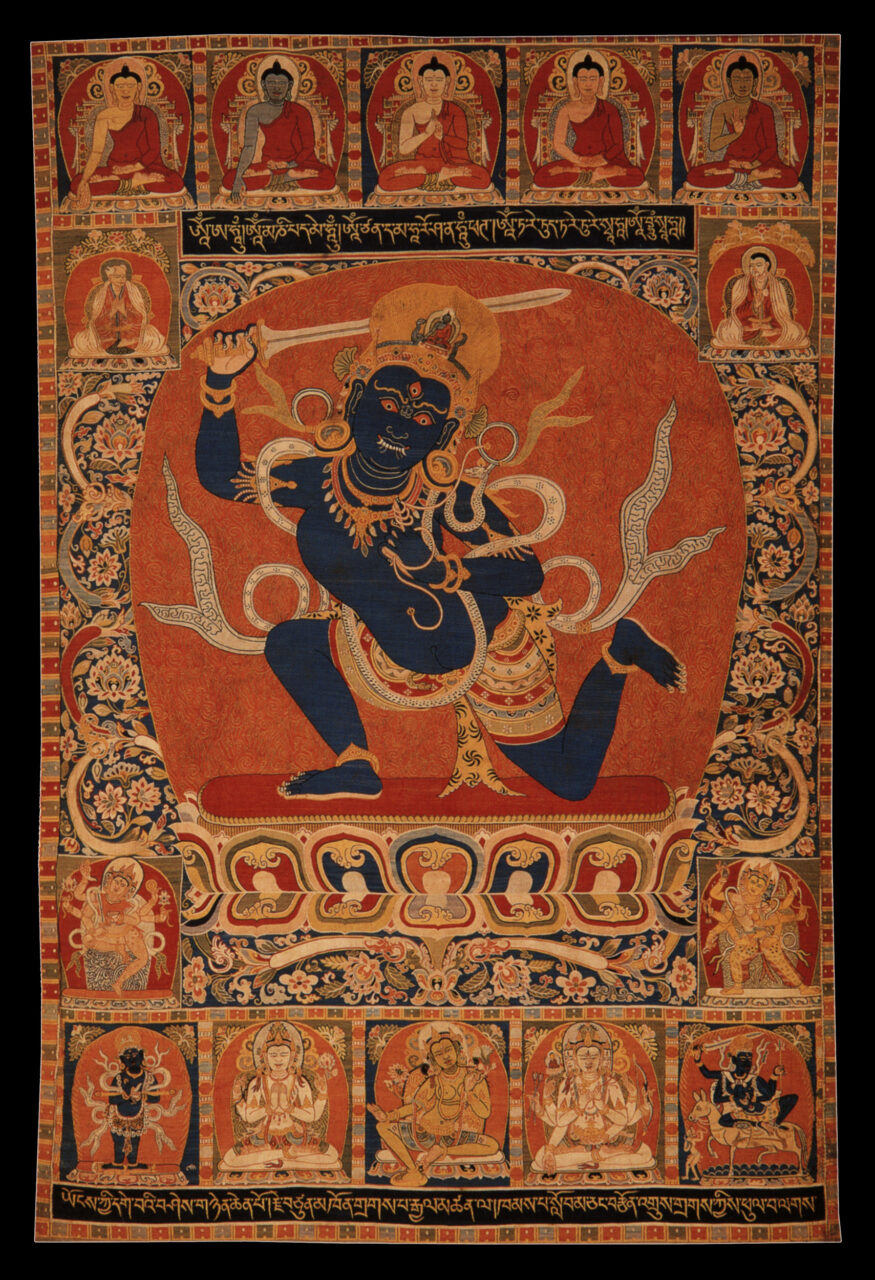

Artists in Tibetan, Himalayan, and Inner Asian traditions work both individually and collectively to produce works, mostly religious in nature, for large monastic institutions, royal courts, and a wide range of individual patrons. While artists were often historically laymen, who passed their traditions down through families and workshops, religious masters who excelled in the arts are often the best known as a result of their exalted religious status, and their works (figs. 5 and 6) became models for emulation and even gave rise to artistic traditions.

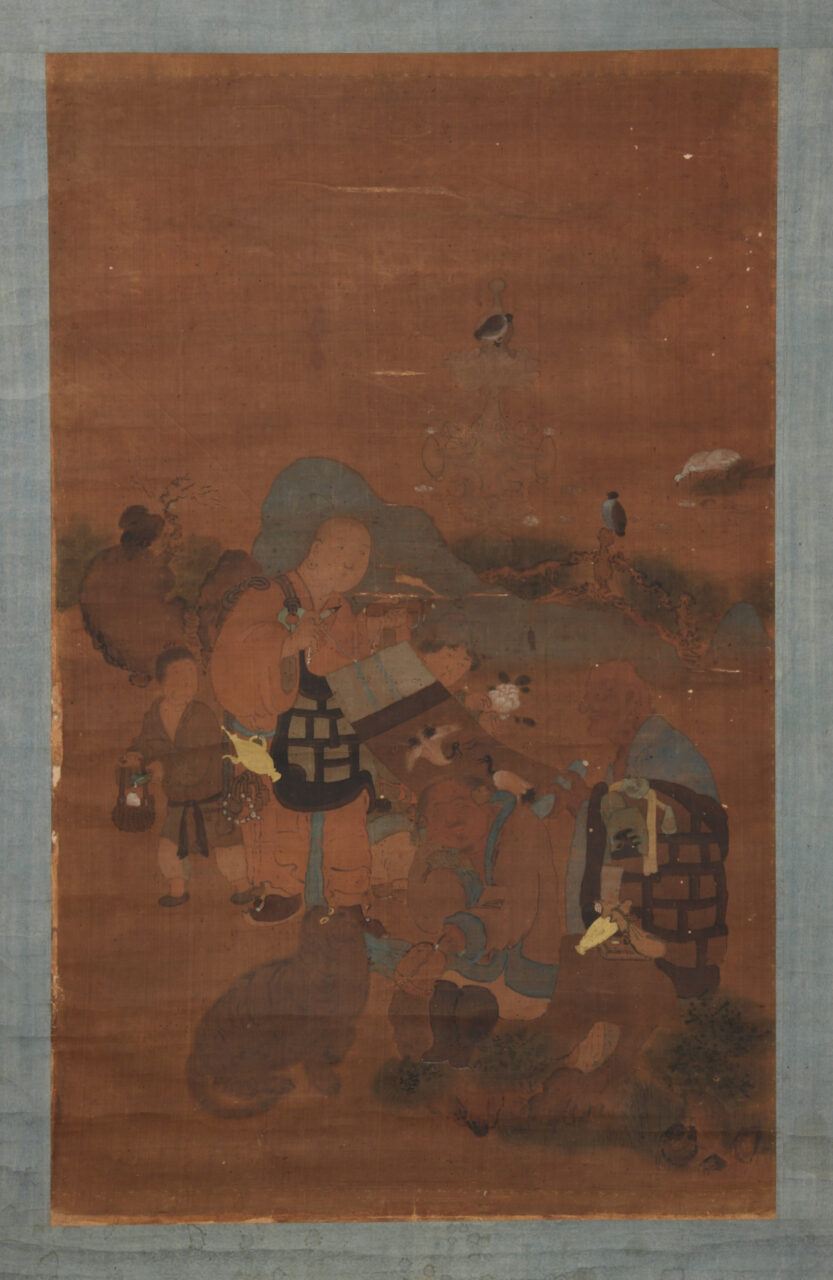

Ghantapa as one of the Eight Great Tantric Adepts; Kham region, eastern Tibet; 18th century; pigments on cotton; 19 × 13 in. (48.3 × 33 cm); The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore; Gift of John and Berthe Ford, 2008; 35.303 (HAR 73821); photograph courtesy The Walters Art Museum

The Wish-Granting Vine Series of One Hundred and Eight Morality Tales, twenty-first painting after Situ’s set; Kham region, eastern Tibet; 19th century; pigments on cotton; 33 × 24 in. (83.8 × 61 cm); Shelley and Donald Rubin Private Collection; P1996.9.5 (HAR 247); photograph by Adam Reich, courtesy the Shelley and Donald Rubin Private Collection

Named Patrons Permalink

Glossary Terms Permalink

Beri is a style of Tibetan painting based on Newar painting of the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal. With the destruction of many Indian monasteries in the thirteenth century, Nepal became an increasingly important source for Buddhist teachers and artisan.

caste

Caste is a traditional system of social division in India and Nepal. The English word “caste” combines two Indic concepts. “Varna” refers to an ancient fourfold division of occupations into priests (brahmins), warriors, farmers, and laborers. In Nepal, the caste system is unique and applies to both Hindu and Buddhists. Like the Hindu brahmins, Buddhist Vajracharya priests and Shakyas are considered the highest caste among the Buddhists, with similar correlations to other social occupational groups. Udas or Uray caste is formed by hereditary merchants and artisans. They are known for their part in the development of industry, trade, arts and culture, and the trade with Tibet. The other ethnic groups traditionally existed largely outside of caste. The caste system was officially abolished in Nepal in 1963.

Encampment Style and New Encampment

The Encampment tradition is an artistic tradition associated with the court of the Karmapas, who traveled in large monastic tent encampments. The painting tradition was established by the artist Namkha Tashi (active ca. 1568–1599). No extant painting by the hand of Namkha Tashi has yet been reliably identified, but religious masters of the Karma Kagyu are said to have urged Namkha Tashi to follow Indian Buddhist models for the figures and Chinese painting for coloring and shading, naming models from the Yuan and Ming courts. The style was revived by Situ Panchen (1700–1774). Sometimes called the “New Encampment” style, these paintings are characterized by open airy landscapes of soft blue and green. The Encampment tradition also included a lesser-known sculptural tradition, founded by the artist Karma Sidrel (d. 1591/92).

The Khyentse artistic tradition of painting and sculpture was founded by Khyentse Chenmo, an artist who worked in central Tibet during the fifteenth century. It is one of two new distinctively Tibetan artistic traditions which arose at this time, the Khyentse and Menla traditions, the first to be named after Tibetan artists, suggesting they are seen as indigenous artistic traditions. These painting styles (Khyenri and Menri) are both known for adopting Chinese landscape into their compositions. Gongkar Chode, near Lhasa, is the only monastery that preserves wall paintings by Khyentse Chenmo’s hand, which he created from 1464 to 1476. His paintings are known for their realism and great attention to detail, particularly in portraits and paintings of wild animals and birds, as well as his depiction of wrathful deities.

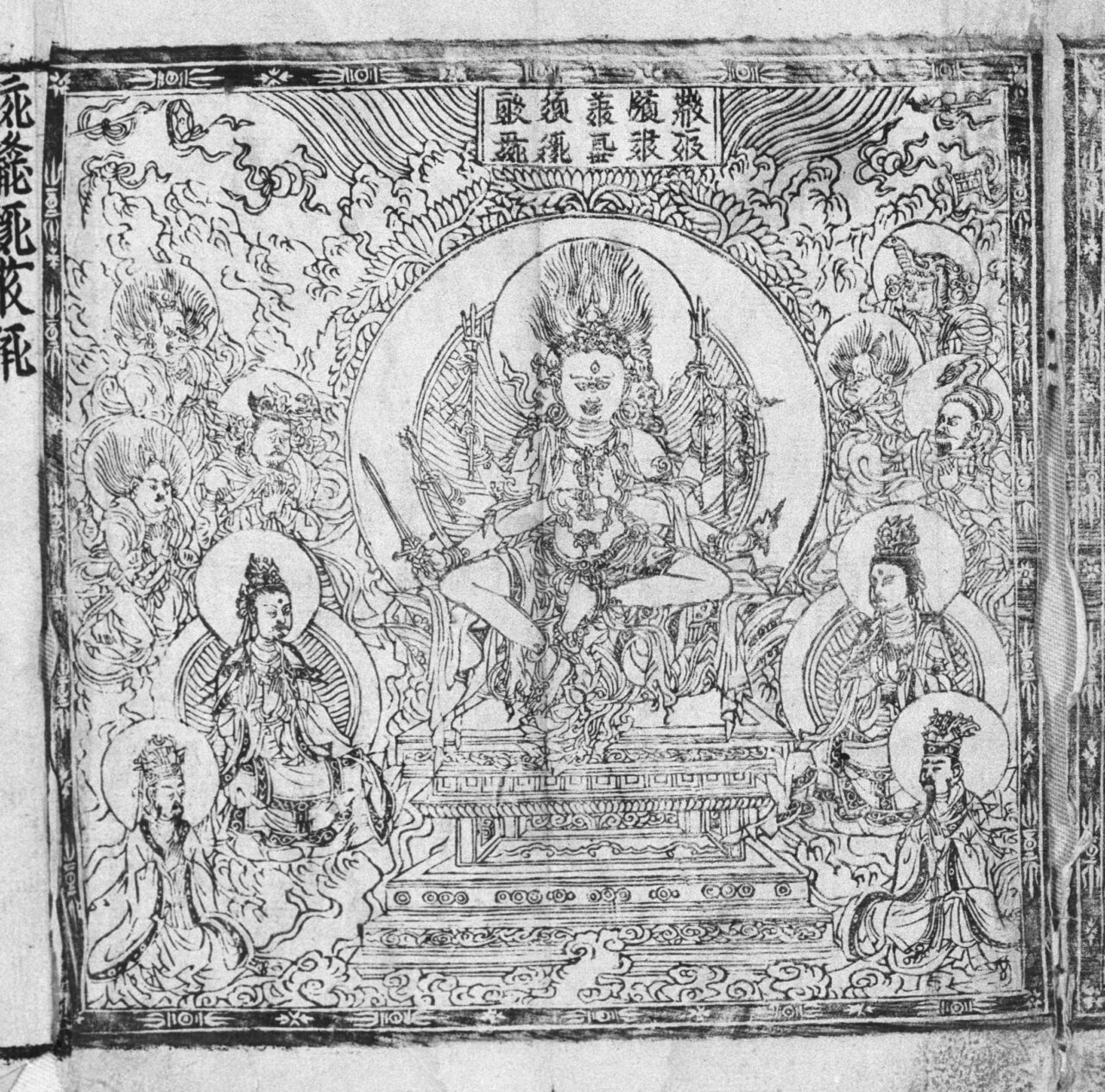

Menla artistic tradition was founded by Menla Dondrup, an artist who worked in central Tibet during the fifteenth century. It is one of two new distinctively Tibetan artistic traditions which arose at this time, the Menla and Khyentse traditions, named after Tibetan artists. These painting styles (Menri and Khyenri) are known for adopting Chinese landscape into their compositions. Menri painting is known to excel in its depiction of peaceful deities. While paintings by Menla Dondrup’s own hand have yet to be reliably identified, a handbook of iconometry, The Wish-Fulfilling Jewel, is attributed to him. The New Menri Style was established by the artist Choying Gyatso (active ca.1640s–1660s) in the court of the Fourth Panchen Lama. Choying Gyatso’s compositions are well known through woodblock prints, characterized by dynamically postured figures set in dramatic Chinese-inspired landscapes.

patronage

A practice of hiring and commissioning artists to create works of art. In religious context patrons were often rulers, religious leaders, as well as ordinary people. (see also donor)

In Newar Buddhism, the Shakya are a hereditary caste descended from Buddhist monks. The name originates from the term Shakya-bikhshu, “Monks of [The Buddha] Shakyamuni.” Shakyas dwell in and manage the former monasteries (Newar: baha, bahi) in the Kathmandu Valley, and some are known metalworkers and makers of religious images.