Hindus and Buddhist believe that all beings die and are reborn in new bodies, or “incarnations.” While reincarnation is recognized across the Buddhist world, in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, some important teachers (lamas) are thought to be able to control this process. Their successive incarnations, known as tulkus (emanation bodies), formed incarnation lineages such as Dalai Lamas, Panchen Lamas, Karmapas, and others.

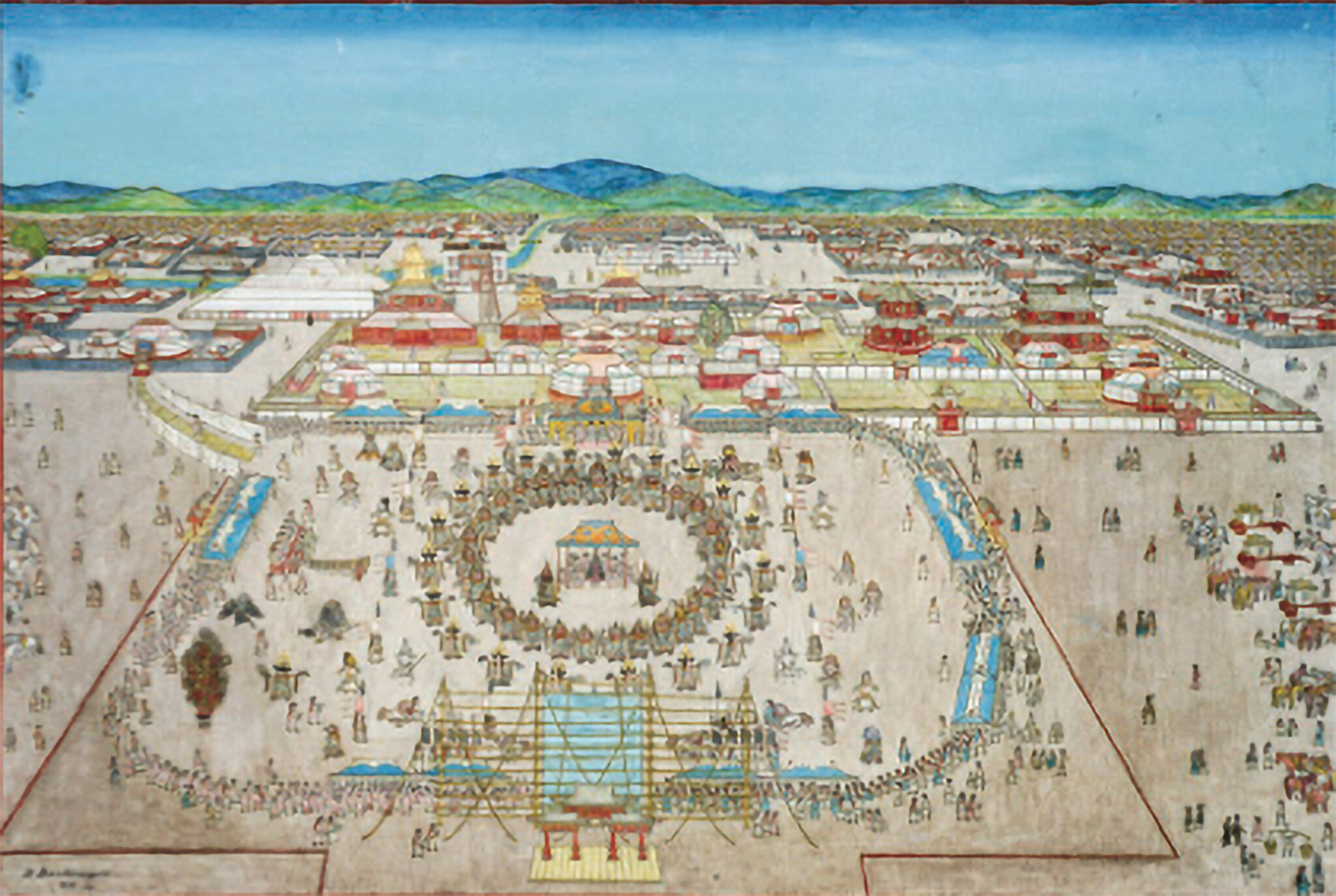

The Jibzundambas (from the Tibetan Jetsun dampa “venerable/reverend noble one”) were the most important lineage of tulkus in Khalkha Mongolia from 1639 to 1924, considered below only the Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas in prestige within the Geluk tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. While the Jibzundamba lineage traces its previous incarnations back to the Tibetan polymath and traveler Taranatha (1575–1634), the first formally enthroned Jibzundampa was the Mongolian prince and artist Zanabazar (1635–1723). As the Jibzundampa’s authority grew, their mobile monastery, called “the great encampment” (Mgl: yekhe khüriye), would gradually settle and develop into Mongolia’s modern capital, Ulaanbaatar. The eighth Jibzundamba ruled as khan of Mongolia from 1911 to 1924.

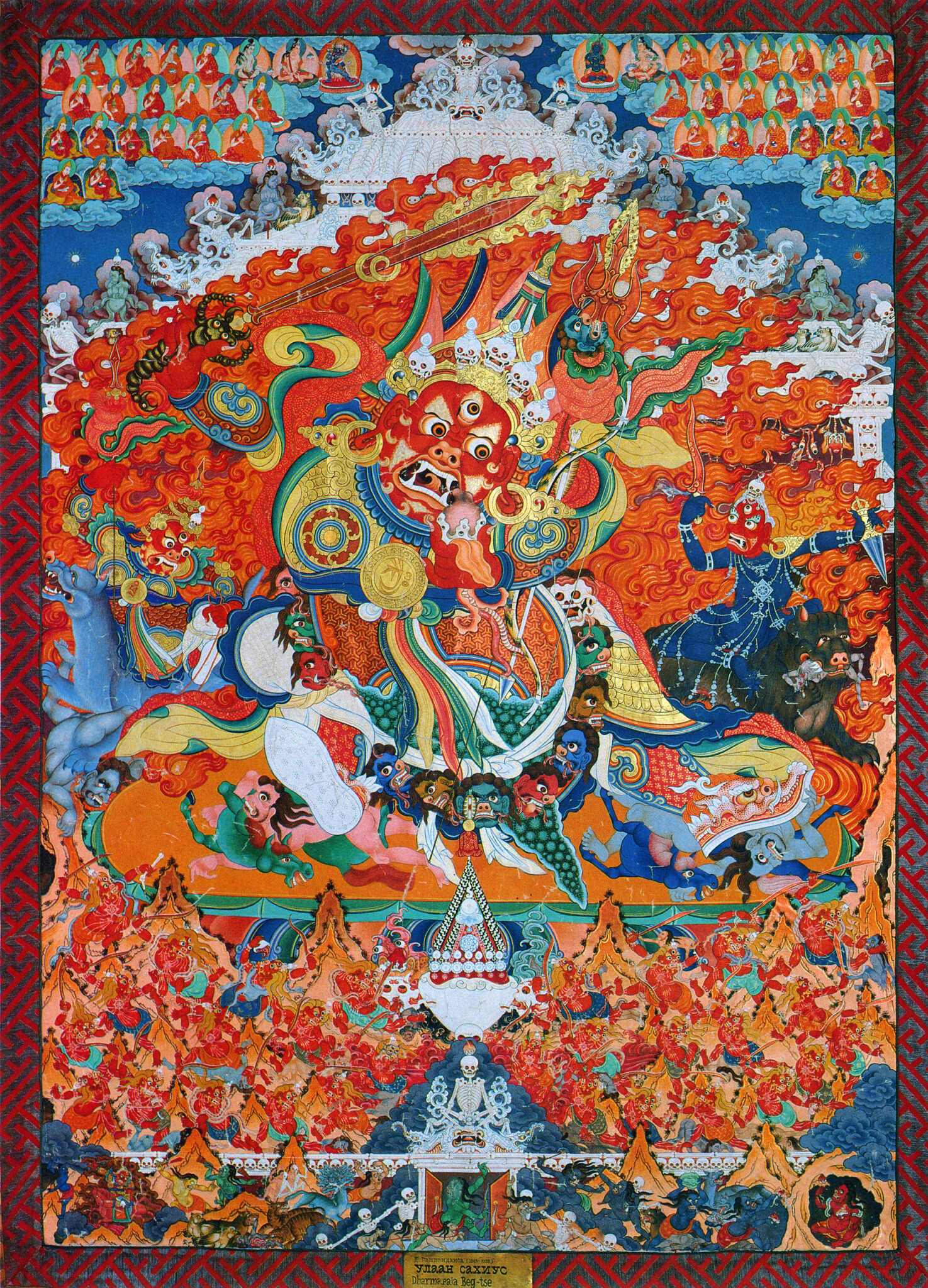

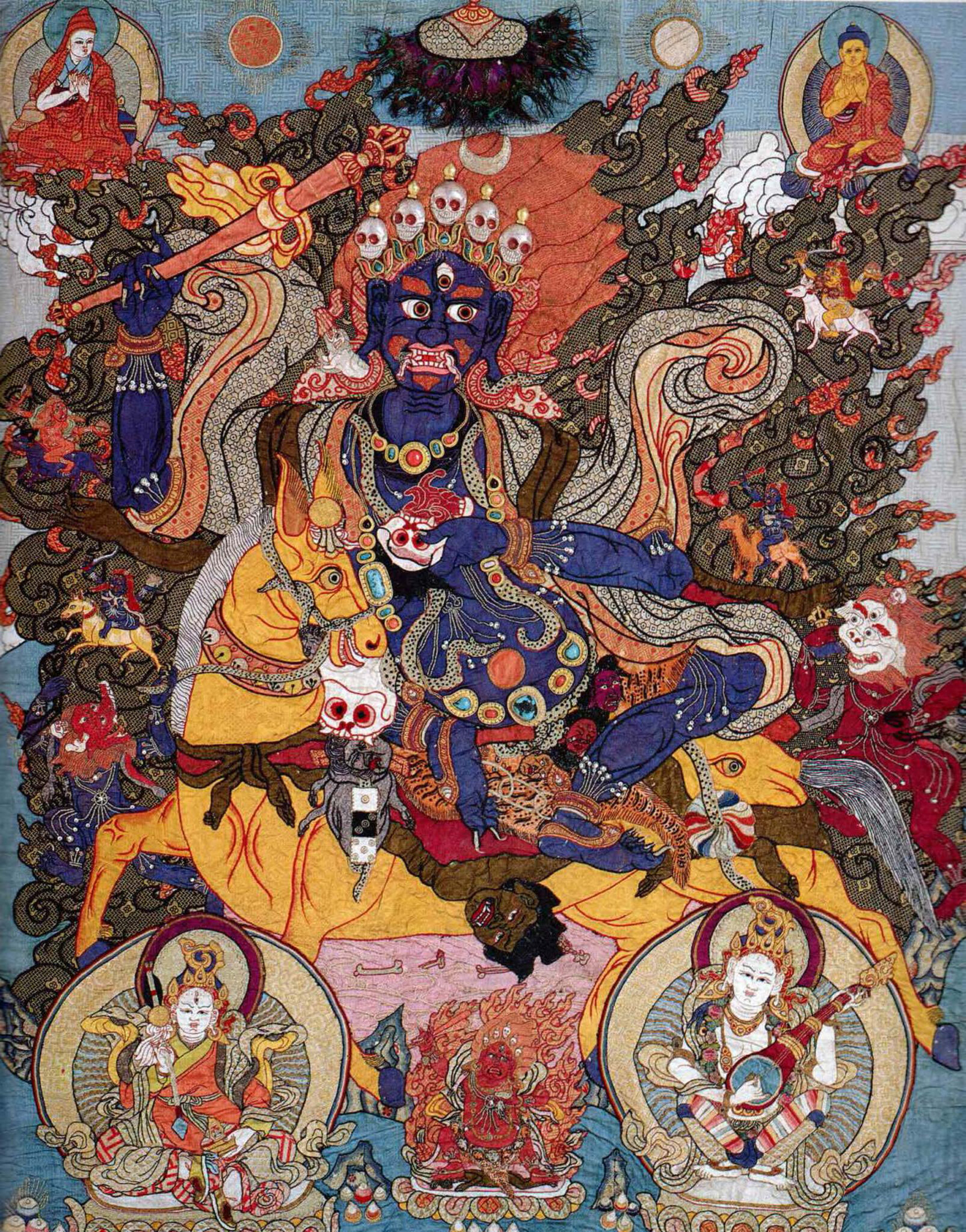

A monastery is a place where monks live, study, and perform ritual. It includes temples and other structures. Monasteries are central to Buddhism, and are also important in Bon, Hinduism, and Daoism. In Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian areas, some monasteries are enormous, wealthy, and powerful institutions, with branches of satellite monasteries forming networks across regions, often with thousands of monks, many decorated chapels, and huge holdings of land. Other monasteries, called hermitages, can be extremely simple, little more than a cave where hermits meditate. Generally, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery will have an assembly hall, several temples (Tib. lhakhang) for worship of specific deities, a protector chapel, as well as monks’ accommodations. A related institution in Newar Buddhism are the baha and bahi.

A practice of hiring and commissioning artists to create works of art. In religious context patrons were often rulers, religious leaders, as well as ordinary people. (see also donor)

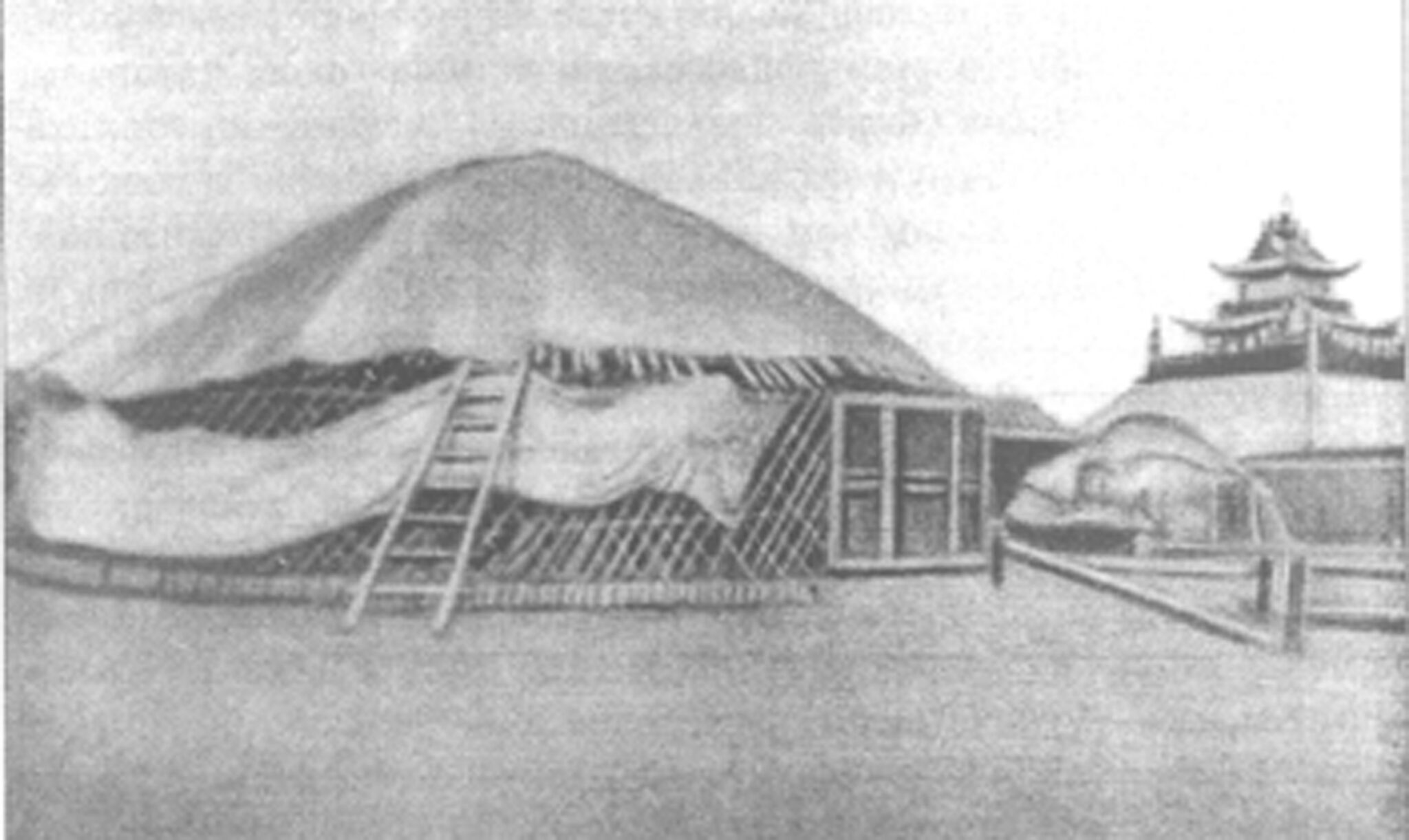

A yurt, called “ger” in Mongolian, is a dome-like tent made of felt and an internal framework of wood slats used by nomads on the steppes of northern Asia. The yurt can be quickly assembled and disassembled and packed for travel and is still being used in Mongolia as a summer home.