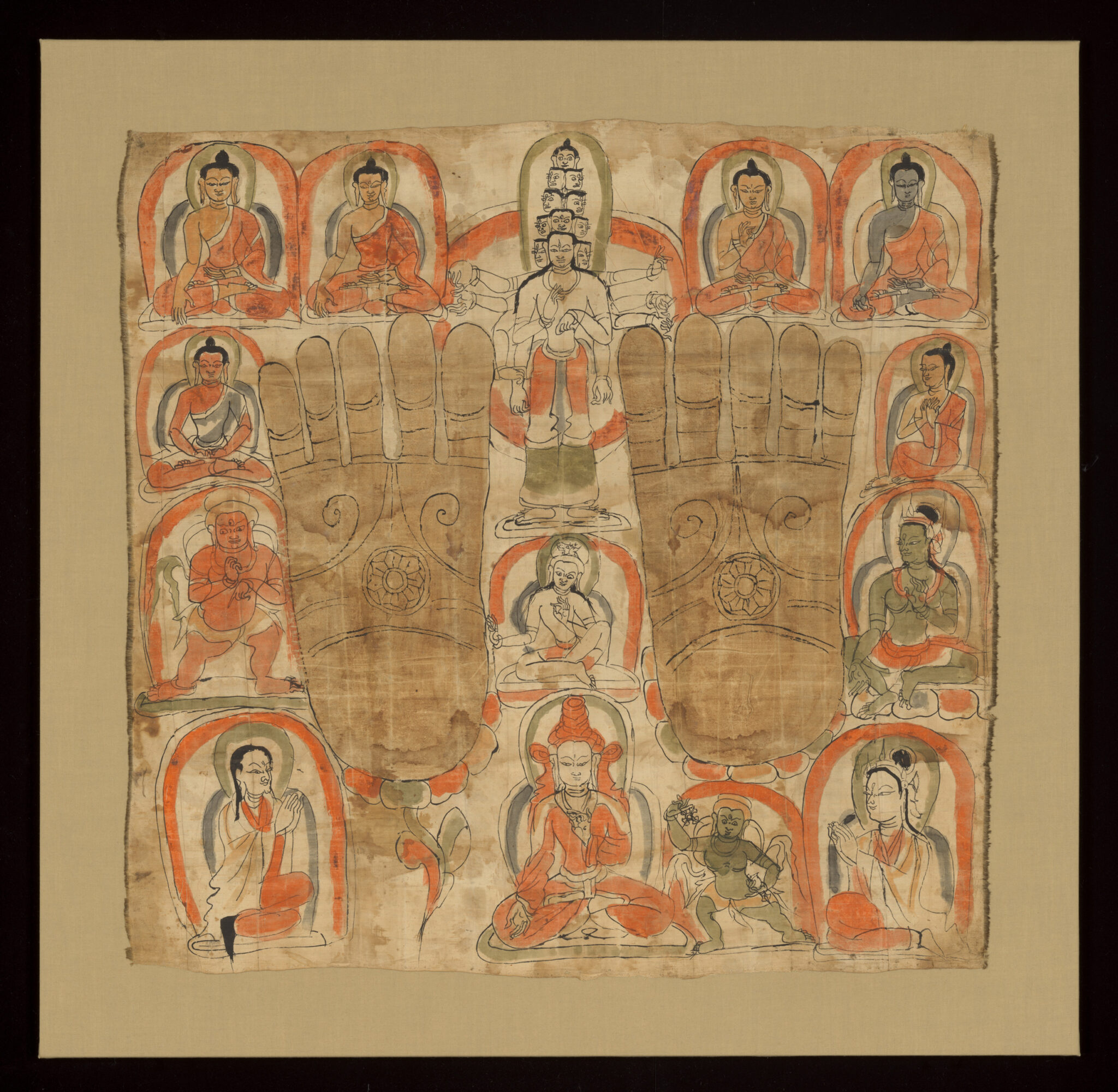

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a being who has made a vow to become a buddha or awakened. In the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, many bodhisattvas are understood as deities with enormous powers who delay their final enlightenment, remaining in the phenomenal world to help suffering beings. Among such great bodhisattvas are Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Maitreya.

Buddha Shakyamuni, or simply “The Buddha,” is an epithet for Siddhartha Gautama, the founder of the Buddhist religion. While the exact dates of Siddhartha’s life are debated, scholars generally place him in the sixth to fifth century BCE. According to early Buddhist narratives, Siddhartha was born a prince of the Shakya clan in what is now northern India and southern Nepal. Choosing to leave his palace and family for a life as a religious ascetic, Siddhartha achieved enlightenment while meditating under the Bodhi Tree. Siddhartha spent the rest of his life as a wandering teacher, gathering disciples to form the early Buddhist monastic community (sangha). Buddha Shakyamuni is revered all over the Buddhist world today.

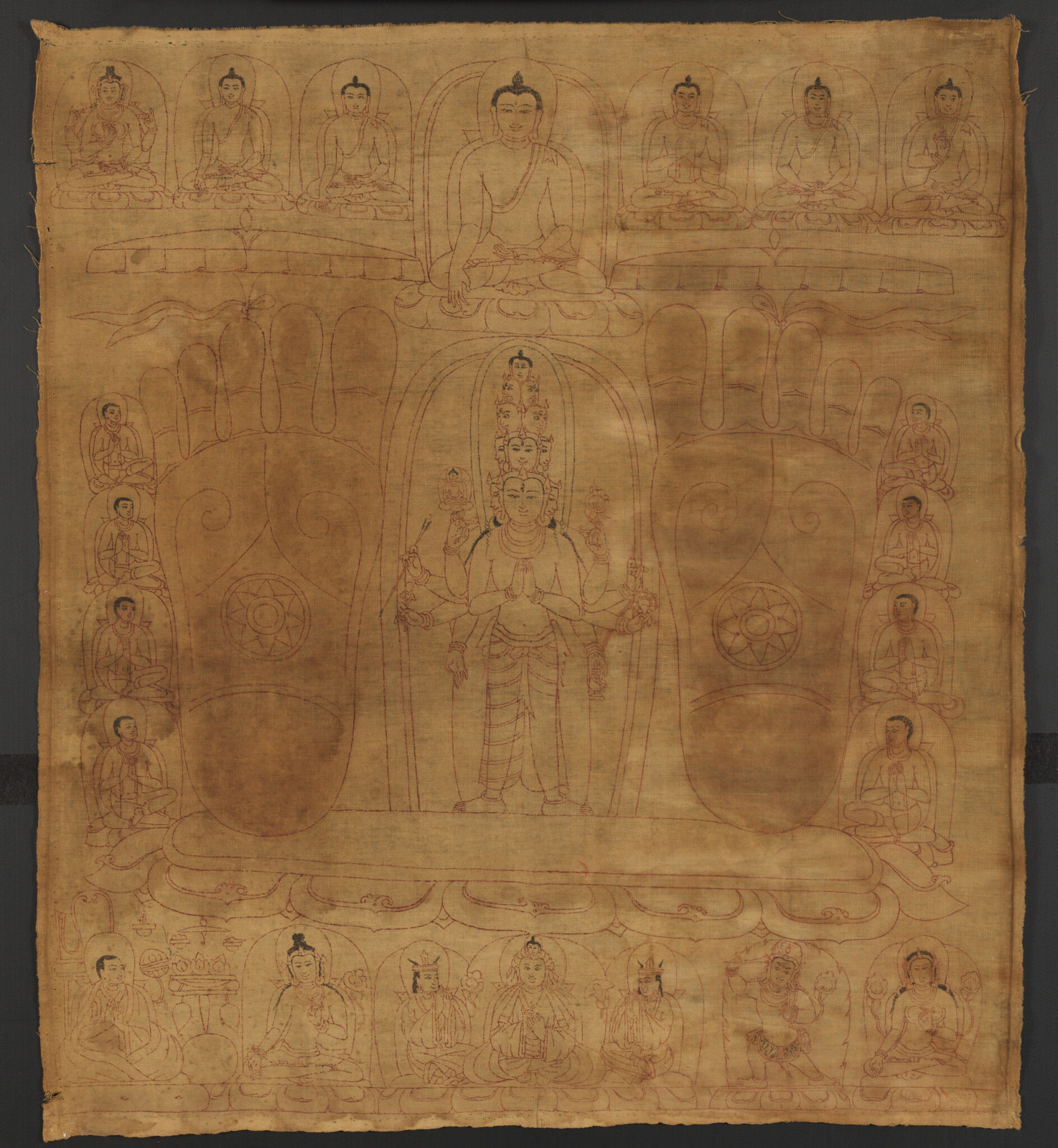

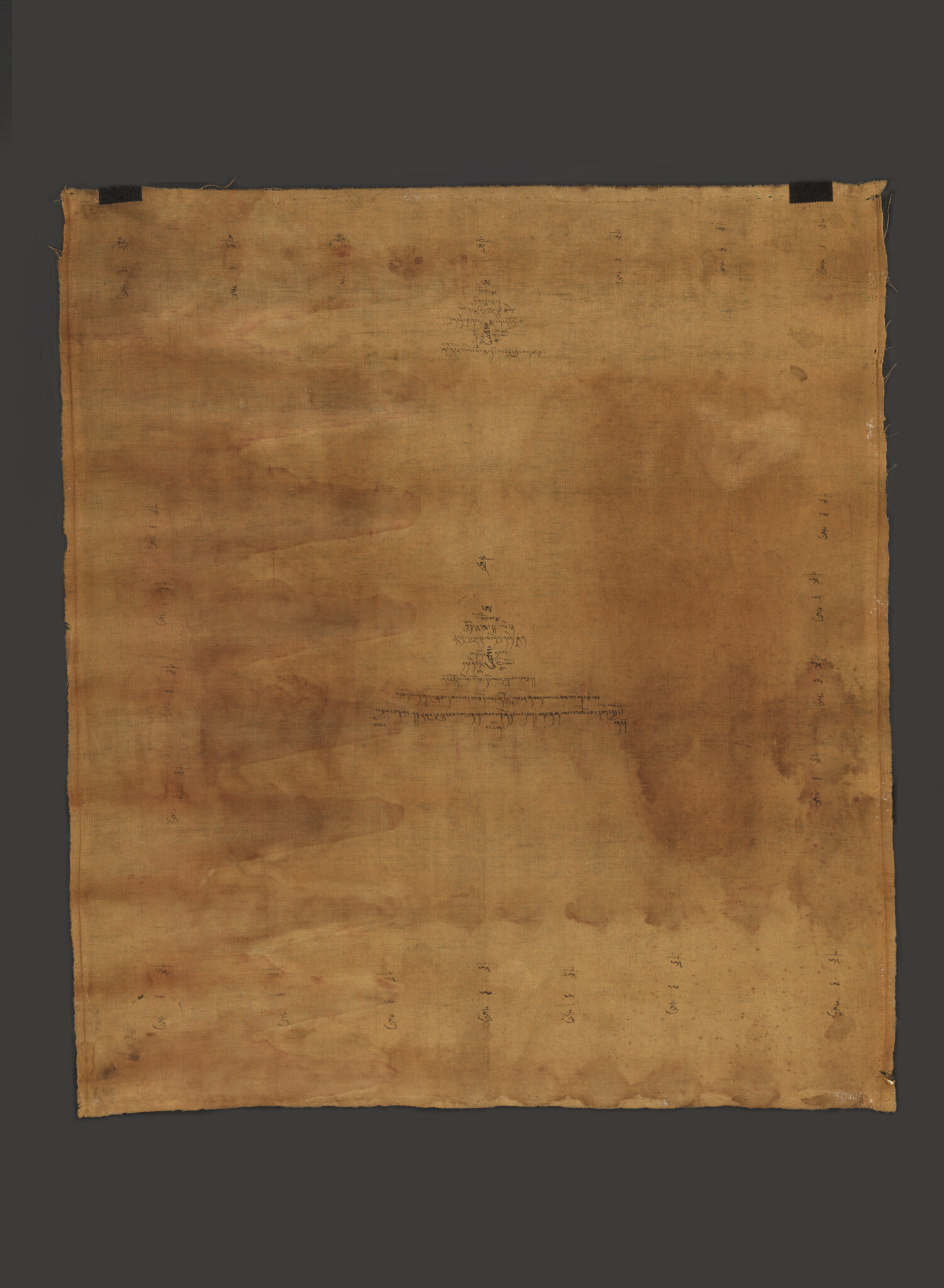

In most Asian religious traditions, when an image of a deity is made, it must be made sacred (“consecrated”) by inviting the deity to inhabit it. A variety of rituals can be involved in this, including dotting the image’s eyes, visualizing the descent of the deity into the image, writing mantras on the back of a thangka, or placing sacred texts and mantras inside of a statue.

Hindus and Buddhist believe that all beings die and are reborn in new bodies, or “incarnations.” While reincarnation is recognized across the Buddhist world, in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, some important teachers (lamas) are thought to be able to control this process. Their successive incarnations, known as tulkus (emanation bodies), formed incarnation lineages such as Dalai Lamas, Panchen Lamas, Karmapas, and others.

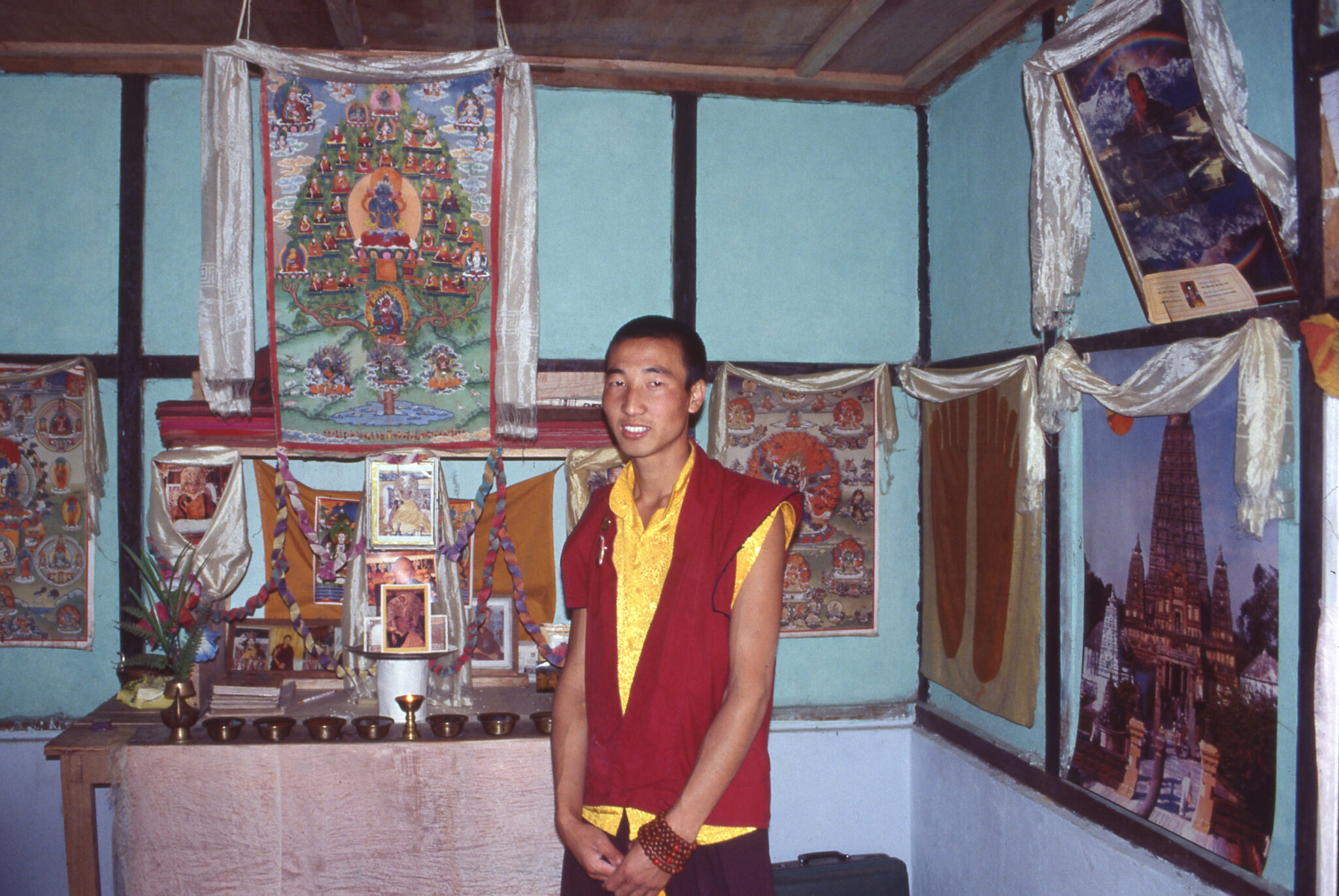

Historically, Tibetan Buddhism refers to those Buddhist traditions that use Tibetan as a ritual language. It is practiced in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, Ladakh, and among certain groups in Nepal, China, and Russia and has an international following. Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in two waves, first when rulers of the Tibetan Empire (seventh to ninth centuries CE), embraced the Buddhist faith as their state religion, and during the second diffusion (late tenth through thirteenth centuries), when monks and translators brought in Buddhist culture from India, Nepal, and Central Asia. As a result, the entire Buddhist canon was translated into Tibetan, and monasteries grew to become centers of intellectual, cultural, and political power. From the end of the twelfth century, Tibetans were exporting their own Buddhist traditions abroad. Tibetan Buddhism integrates Mahayana teachings with the esoteric practices of Vajrayana, and includes those developed in Tibet, such as Dzogchen, as well as indigenous Tibetan religious practices focused on local gods. Historically major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism are Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Geluk.

In the early seventh century, a line of kings from the Yarlung Valley united disparate people on the Tibetan Plateau into a powerful, centralized state. With their capital at Lhasa, these kings proclaimed themselves emperors, or tsenpo. Their armies conquered much of the Himalayas, Central Asia, and western China. Tibetans developed a written script for the Tibetan language and Buddhism was adopted as a state religion. The conversion to Buddhism was contested by an indigenous group of ritualists called Bon, creating political turmoil. After the assassination of emperor Langdarma in 842, the Tibetan empire fragmented and collapsed. Nevertheless, the myths and memories of the empire continue to be a central part of Tibetan identity.