The Dalai Lamas are a tulku lineage that has played a central role in Tibetan history for the last five hundred years. In 1577 a Mongol khan gave the Geluk monk Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588) the title “Dalai Lama,” combining the Mongolian word for ocean, dalai (a reference to the depth of his knowledge), and the Tibetan word for guru, lama. Later, two previous incarnations were retroactively identified. The fifth incarnation, Ngawang Gyatso (1617–1682), allied with another Mongol khan to unite most of the Tibetan Plateau, forming the Ganden Podrang government that would govern Tibet until 1959. Since the Communist takeover, the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama has lived in exile at Dharamshala in India. The Dalai Lamas are understood to be emanations of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

In Buddhist context, donor is a person who contributes to or commissions a religious work of art. This act is intended to increase merit on behalf of the benefactor and is dedicated to the benefit of all. It is also usually done for a specific purpose, such as longevity, prosperity, or well-being; to advance religious practice; or to ensure a good rebirth of a deceased relative, teacher, or friend. A similar practice is also known in Hinduism and Bon.

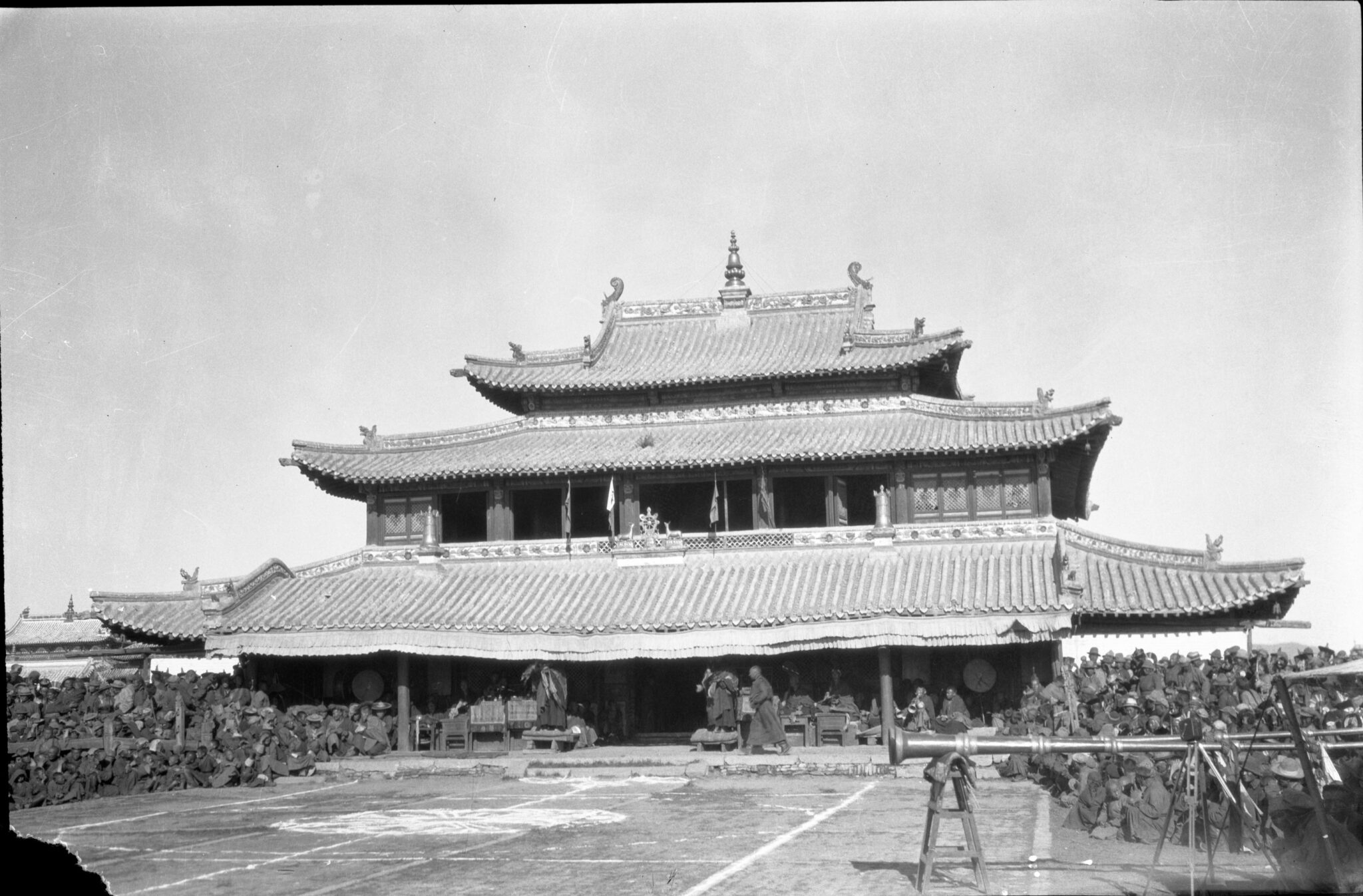

The Jibzundambas (from the Tibetan Jetsun dampa “venerable/reverend noble one”) were the most important lineage of tulkus in Khalkha Mongolia from 1639 to 1924, considered below only the Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas in prestige within the Geluk tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. While the Jibzundamba lineage traces its previous incarnations back to the Tibetan polymath and traveler Taranatha (1575–1634), the first formally enthroned Jibzundampa was the Mongolian prince and artist Zanabazar (1635–1723). As the Jibzundampa’s authority grew, their mobile monastery, called “the great encampment” (Mgl: yekhe khüriye), would gradually settle and develop into Mongolia’s modern capital, Ulaanbaatar. The eighth Jibzundamba ruled as khan of Mongolia from 1911 to 1924.

A monastery is a place where monks live, study, and perform ritual. It includes temples and other structures. Monasteries are central to Buddhism, and are also important in Bon, Hinduism, and Daoism. In Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian areas, some monasteries are enormous, wealthy, and powerful institutions, with branches of satellite monasteries forming networks across regions, often with thousands of monks, many decorated chapels, and huge holdings of land. Other monasteries, called hermitages, can be extremely simple, little more than a cave where hermits meditate. Generally, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery will have an assembly hall, several temples (Tib. lhakhang) for worship of specific deities, a protector chapel, as well as monks’ accommodations. A related institution in Newar Buddhism are the baha and bahi.

Stupas are monuments that initially contained cremated remains of Buddha Shakyamuni or important monks, his disciples, and subsequently other material and symbolic relics associated with the Buddha’s body, teaching, and enlightened mind. As representations of the Buddha’s presence in the world, stupas with their contents—texts, relics, tsatsas—continue to be important objects of Buddhist worship in their diverse forms of domed structures, multistoried pagodas, and portable sculptures. The original form of stupas was an earthen dome-shaped mound containing the remains in reliquary vessels or urns deposited within the innermost core. The dome would often be successively enlarged and surrounded by a path for a walk around in a clockwise direction and veneration (circumambulation)

Historically, Tibetan Buddhism refers to those Buddhist traditions that use Tibetan as a ritual language. It is practiced in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, Ladakh, and among certain groups in Nepal, China, and Russia and has an international following. Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in two waves, first when rulers of the Tibetan Empire (seventh to ninth centuries CE), embraced the Buddhist faith as their state religion, and during the second diffusion (late tenth through thirteenth centuries), when monks and translators brought in Buddhist culture from India, Nepal, and Central Asia. As a result, the entire Buddhist canon was translated into Tibetan, and monasteries grew to become centers of intellectual, cultural, and political power. From the end of the twelfth century, Tibetans were exporting their own Buddhist traditions abroad. Tibetan Buddhism integrates Mahayana teachings with the esoteric practices of Vajrayana, and includes those developed in Tibet, such as Dzogchen, as well as indigenous Tibetan religious practices focused on local gods. Historically major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism are Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Geluk.