Golden Fountain of Bhaktapur

Bhaktapur, Nepal 1688Spout of Golden Fountain of Bhaktapur Palace; Bhaktapur, Nepal; 1688; stone, repoussé metalwork; dimensions unknown; photograph by Christian Luczanits, 2010

Architectural Expression of Monsoonal Phenomena

Spout of Golden Fountain of Bhaktapur Palace; Bhaktapur, Nepal; 1688; stone, repoussé metalwork; dimensions unknown; photograph by Christian Luczanits, 2010

Spout of Golden Fountain of Bhaktapur Palace; Bhaktapur, Nepal; 1688; stone, repoussé metalwork; dimensions unknown; photograph by Christian Luczanits, 2010

Nepalese art scholar Gautama Vajracharya examines the famous golden fountain head in Nepal. Designed in glittering metalwork, the spout’s fantastical animated scenes of mostly aquatic animals are derived from Vedic stories of life-giving rain. The standout feature is the mythical sea creature makara with a goat leaping from its gaping mouth. These and images of frogs, snakes and other creatures relate to the monsoon and signify fertility and auspicious abundance.

In Hinduism, Kubera is a god of wealth and a king of nature spirits, called yaksha. In Buddhism, he is often equated with the wealth deity Jambhala, and is also one of the eight horsemen-generals in the retinue of the god Vaishravana, the guardian king (lokapala) of the North.

In Indic mythology, a makara is a mythical crocodile-like creature that lives in rivers and lakes and is generally associated with water. In Himalayan art, certain deities are depicted as riding makaras. More commonly, makaras appear as decorative motifs on either side of gateways, or around the torana. In Newar art of the Kathmandu Valley they represent a rain cloud and appear as aquatic creatures with teeth and a curling elephant trunk-like snout.

The monsoon is the yearly rain season in the Indian Subcontinent and the Himalayas. Depending on the area, the monsoon lasts roughly from midsummer to late autumn. Monsoon is the main source of water for the Kathmandu Valley and central to agrarian and ritual life of the Newars.

Nagas are powerful serpent spirits that live in lakes, rivers, and seas. In Indian religions, including Hinduism and Buddhism, nagas are believed to control rain, and therefore agricultural prosperity. Nagas can be helpful or harmful, and there are many stories and rituals involving them. Indian Buddhist tales about nagas have been assimilated to similar beings in indigenous Tibetan, Chinese, and Mongol mythologies, including Tibetan serpent-spirits (Tib. “lu”) and Chinese dragons (Ch. “long”). A female naga is called a “nagini,” while the kings of the nagas are called “nagarajas.”

The Newars are traditional inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal. The Newars speak a Tibeto-Burman language (Newari) and practice both Hinduism and Buddhism. The Newars are inheritors of one of the oldest and most sophisticated urban civilizations of the Himalayas, and Newar arts and artisans have been celebrated all across the Himalayan world since the Licchavi period.

The Rigveda is the oldest section of the Indian Vedas, and the oldest texts of the religion now called Hinduism. Written in Sanskrit sometime in the second millennium BCE, the Rigveda consists of poetic hymns to the early Hindu gods, including Indra, Agni, Vishnu, and others. Also important is soma, an intoxicating drink that allows the Vedic sages to directly contact the gods. Hindus still read the Vedic hymns today, making it probably the oldest continuously used religious text in the world. For scholars, the Rigvedas are a crucial window into the very early stages of Indic society and religion.

The art of Nepal is deservedly famous not only for the -like architecture of the Kathmandu Valley, site of the capital of the country, but also for the subterranean architecture that provided water through the cities of the valley. The surface fountains feature horizontally projecting spouts designed after the mythical , a creature that symbolizes water, both celestial (rain cloud) and terrestrial. Usually, the makara spout is made from stone, but in royal palaces the stone spouts, as in this example, are often covered with tastefully designed, glittering metalwork.

The natural sources of water for all fountains in the Kathmandu Valley are the lakes situated on the slopes of the mountains surrounding the valley and fed by rains. Although the lakes are within ten or twenty miles of the cities, it was not an easy job to build subterranean brick canals with catch basins, even for short distances. The earliest, fifth-century water fountain of the valley is still functioning. The seventeenth-century golden fountains of the three royal palaces of the valley, in Bhaktapur, Patan, and Kathmandu (fig. 2), are examples of the continuation of the much earlier custom.

Locations of Bhaktapur, Kathmandu, and Patan in the Kathmandu Valley

Older generations of , the natives of the valley, still remember that the real name of the golden fountain of Bhaktapur is the Goat Fountain (Duguca Hiti). The golden fountain of Patan palace is known as the Cow Fountain (Thusa Hiti). These names derive from the dramatic representation of animated images of a crying goat, as seen here, or a cow leaping from the mouth of the makara. Although the cow is now missing from the Patan fountain, the domesticated animal repeatedly appears in other examples. Another fascinating feature of the fountains is the three-dimensional image of a scaly creature resembling a pangolin crawling on top of the spout.

The Bhaktapur fountain is highly admired for the elaborately designed scenes crowded by a variety of creatures, mostly aquatic, depicted on the panels on both sides of the spout (fig. 3). At the uppermost section of the scenes, male and female , “divine serpents,” intertwine as they mate. Below the erect head of the divine serpent, an enormous, diagonally projecting boar with sharp teeth and tusks is about to jump out of the group. The boar is trampling a running baby horse that is about to jump over a very large conch shell. Behind this scene, a baby goat, a bird, and a turtle are rendered naturalistically. They are followed by equally animated representations of a ram and a frog. Behind the ram crowd a quacking duck and the head of a large fish that appears to be about to leap out of the muddy water. At the very end of the panel, a half-bird mythical creature known to the Newars as jalamanusha, “aquatic man,” faces the other creatures.

During the medieval period (879–1769), it was customary to place an image of Prince Bhagiratha below the fountain’s spout. According to legend, the prince was responsible for bringing the atmospheric Ganga River down to the earth, when all the water on earth, including the oceans, had dried up in a severe drought. Here, a stone statue of the prince occupies the wall immediately below the spout (fig. 4). He holds a lotus with his right hand and blows a conch shell to announce the joyful arrival of the rain river. This image of Bhagiratha conveys the message that the makara fountain symbolizes the Ganga’s descent.

Detail of Golden Fountain of Bhaktapur Palace, showing stone statue of a prince under spout; Bhaktapur, Nepal; photograph by Christian Luczanits, 2010

The association of Bhagiratha’s story with Nepalese fountains does not seem old enough to be original. During the ancient period of Nepalese history (ca. 200–ca. 879), a stone relief of one or a pair of earth spirit (yaksha) figures almost always occupied the wall below the spout exactly where Bhagiratha appears in later examples. They reside beneath the earth and support it; their representation is associated with the legend of the disappearance of the Sarasvati River in northwest India. During the Vedic period (1500–600 BCE) the river was still flowing, but dwindling, and eventually it vanished at a place called Vinasana, or “disappearance.” People thought that the river had emptied into the netherworld. Almost certainly, the yakshas below the spout symbolize the Sarasvati River rather than the Ganga.

Prominent features of the water fountain, however, such as the representations of mating serpents, a frog, and the domesticated animal coming out of the makara’s mouth, do not directly relate to these rivers. A frog (figs. 5 and 6)—shown here on the spout, but in other examples also above the spout crawling together with the pangolin-like scaly creature—holds the key to understanding the symbolism of the water fountain that developed over the millennia, some of it going back to the Vedic period or even earlier.

Detail of Fountain outside Bhaktapur Palace, showing sculpted stone spout; Bhaktapur, Nepal; 1688; photograph by Gautama Vajracharya

The Vedic and pre-Vedic cowherds living near the southern slope of the Himalayas believed that frogs were divine beings capable of making rain. This belief related to an ancient technique of cow breeding. The ancient cowherds wanted their cows to conceive around autumn so that calves would be born at the beginning of the monsoon season when there is plenty of vegetation for feed. They kept bulls away from the cows and released them only after an autumnal ritual. Because frogs start croaking with the onset of the monsoon rain, their croaking coincided with the birth of the calves. The ancient people thought that it rains when frogs start croaking. In the well-known frog hymn of the , the frogs were prayed to in the hopes of the birth of multiple calves. According to some Vedic poets, a variety of creatures descend from heaven together with the shower of rain. The crowded scenes of creatures depicted on the spout of the golden fountain are indeed associated with this belief.

Like the Vedic people, the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley originally were cow breeders. Amazingly, they still worship the frogs and celebrate the autumnal festive days of the impregnation of cows and monsoonal birth of calves in accordance with the Vedic or pre-Vedic calendar. Admittedly, the real meaning of the annual celebrations is now nearly forgotten, but the ancient Newars who adorned the water fountains with symbolic creatures certainly knew the reason for juxtaposing the image of a frog with a calf or a goat emerging from the mouth of a makara.

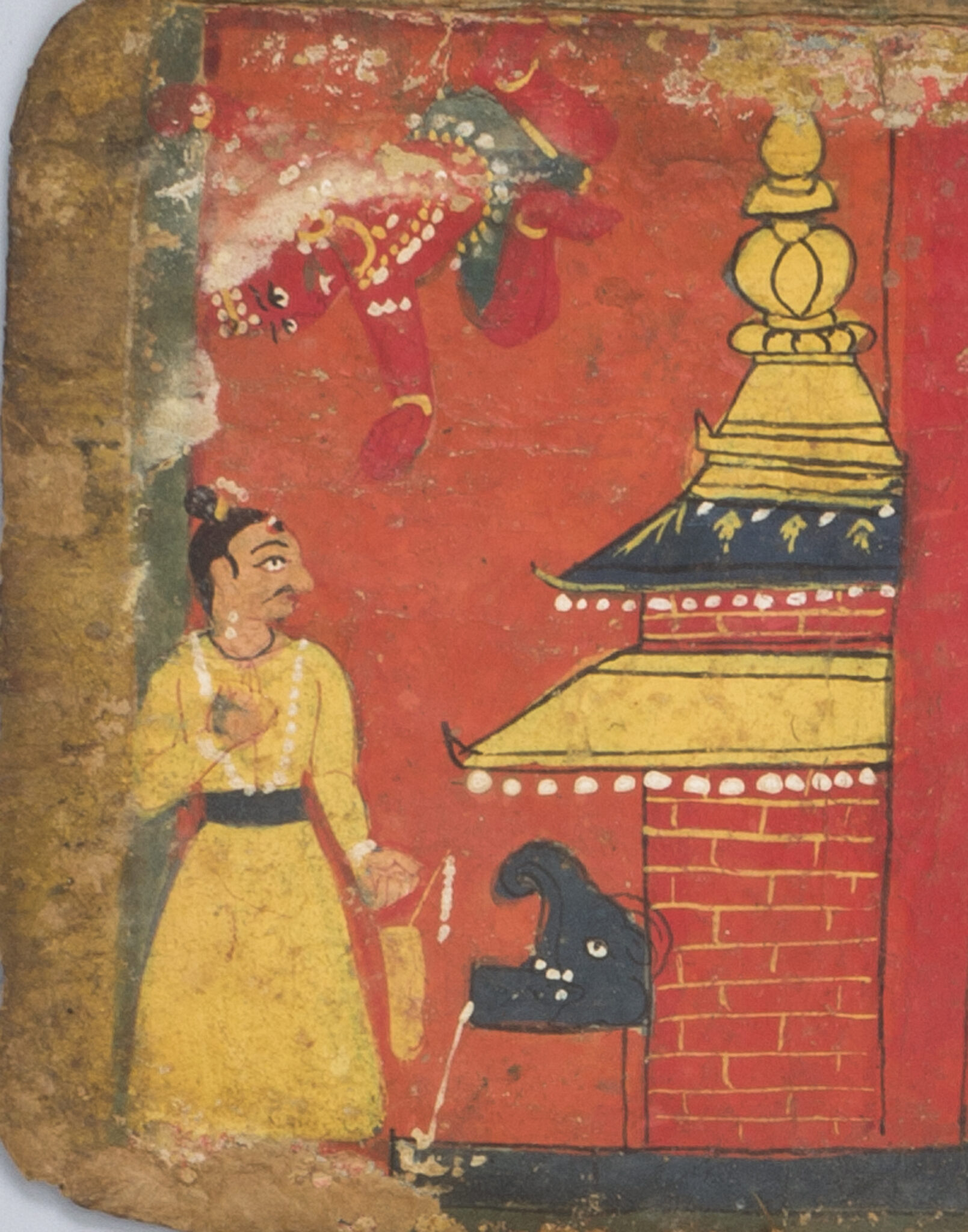

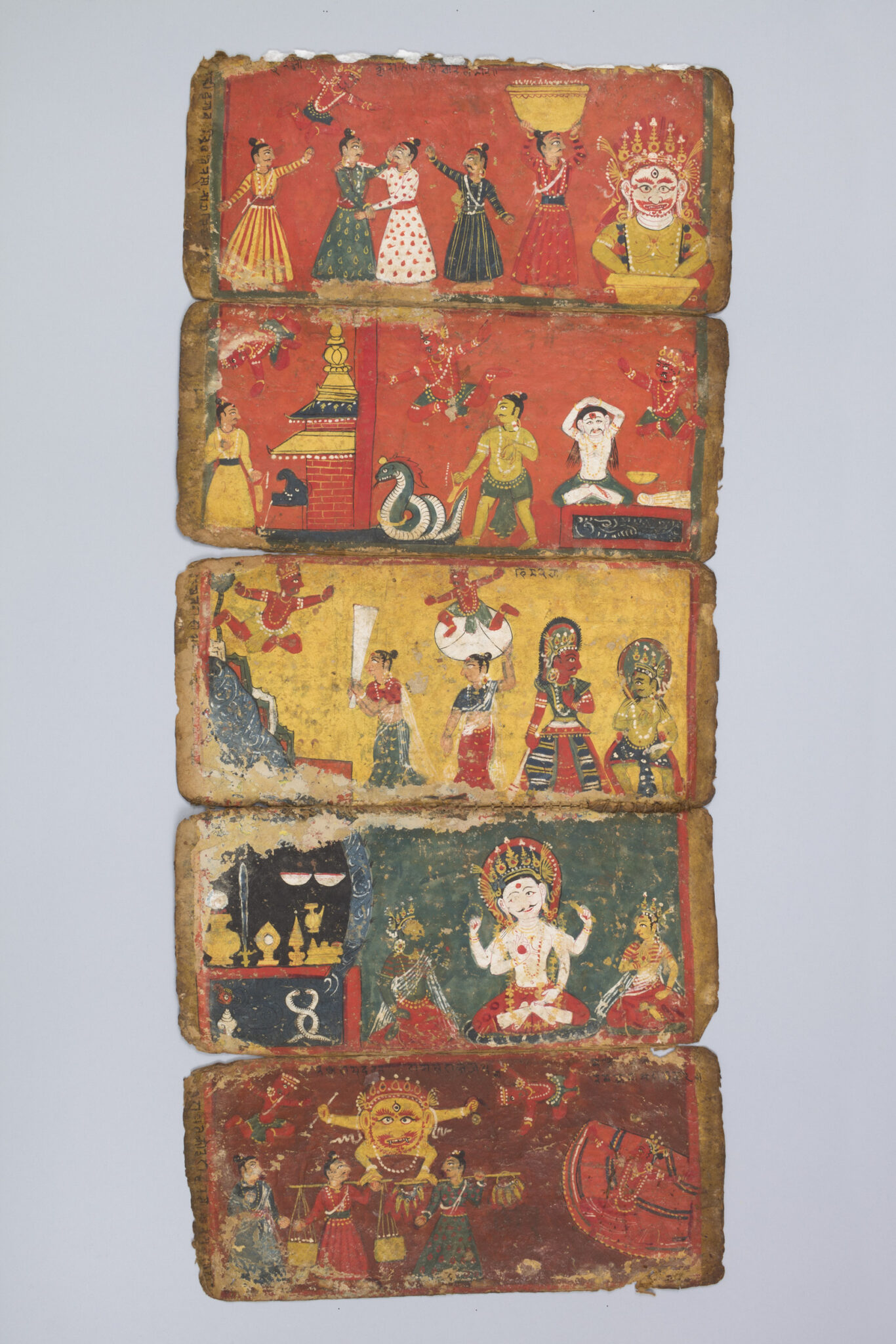

In , a synonym for makara is dhara, which means “the shower of rain.” In addition, in artworks, the lower body of the makara is carved in a popular motif known as abhrapatra, or “cloud foliage.” In fact, the makara is an atmospheric creature visualized in the cloudscape of monsoonal rain. Thus, the depiction of a frog and calves on the fountains in the valley indicates that the Nepalese water fountains are the architectural expression of monsoonal phenomena. For this reason, in the Nepalese painterly tradition, drought is symbolically depicted by a dry makara fountain with a human figure standing in front of the spout, begging for water (fig. 7, top right panel of fig. 8), whereas the joyful arrival of the monsoon rain is pictured by a stream of water flowing from the mouth of the dhara/makara (fig. 9, second folio from the top, left scene of fig. 10). The beginning of the monsoon is also the mating time of snakes. Like frogs, snakes aestivate in the summer and become active with the arrival of the rains. Thus, the auspicious mating serpents are shown on both sides of the spout of the Golden Fountain.

Detail of Bunga Dyo, the Legend of Red Avalokiteshvara, showing a dry makara fountain; Nepal; 1712; pigments on cloth; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Purchased with the Stella Kramrisch Fund, 2006; 2006-136-1; photo courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art

Bunga Dyo, the Legend of Red Avalokiteshvara; Nepal; 1712; pigments on cloth; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Purchased with the Stella Kramrisch Fund, 2006; 2006-136-1; photo courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art

Detail of Illustrated Manuscript Depicting the Story of Water, showing the end of drought with a running makara fountain; Nepal; 17th century; pigments on paper; Rubin Museum of Art; F1996.31.33 (HAR 100018)

Illustrated Manuscript Depicting the Story of Water; Nepal; 17th century; pigments on paper; Rubin Museum of Art; F1996.31.33 (HAR 100018)

Sanskrit literature tells us that the cosmos has two oceans, atmospheric and terrestrial, and that the source of water is the former. When the gods block the flow of atmospheric water, the rains stop, causing severe droughts. This view remained intact throughout the history of the ancient and medieval periods. In Nepalese art, an ocean is represented by aquatic and mythical creatures, including makara-like crocodiles, serpents, conch shells, and jalamanushas. All these creatures flow down to the terrestrial realm when the atmospheric water descends to the earth. According to Pali literature, the rain cloud is the god lake, which is explained as the source of rainwater. In this literature, however, jalamanushsa is designated as danda–manavaka, or “Lotus Baby.”

The concept of the cloud ocean or lake intertwines with another interesting view: that just like cows, the sky conceives in autumn and gives birth to rain babies when the monsoon arrives. Astrological texts say that if aquatic and semiaquatic creatures appear in the cloudscape, it means the sky has conceived. It is this view that inspired the artists of the Ajanta ceiling painting (fig. 11) in which aquatic and semiaquatic creatures inhabit Kubera’s cloud lake and peep out of the stylized cloud (abhrapatra). A remarkable feature of the ceiling painting is a fully grown fetus whose lower body morphs into cloud foliage. Sometimes, the umbilical cord of the fetus is depicted as a stylized lotus vine, which must be the reason that the atmospheric baby was named Lotus Baby in Pali literature. It is this lotus baby that went through metamorphosis and became the jalamanusha in Nepalese art (fig. 12).

Cave no. 1, Ajanta, Aurangabad District, Maharashtra, India; photograph by Nikreates / Alamy Stock Photo

Jalamanusha (Merman); Nepal; ca. 13th century; copper alloy; 7¼ × 9 × 5 in. (18.4 × 22 × 12.7 cm); Collection of David R. Nalin, MD

Artistically, the Golden Fountain is the epitome of both water architecture and repoussé work. Making repoussé requires a special skill and vision. The artist creates an image by hammering it into relief from the reverse side and needs to visualize the appearance of the image in negative, which seems to be why Newar artists prefer to call it thvajya, or “echo work.” For many centuries Nepalese artists excelled in repoussé.

The unknown artist of this fountain deserves special admiration for creating a superlative composition. He understood how to exploit the play of light and shadow across the surface of the relief, which makes most of the creatures appear to emerge from an invisible deeper space. Subtle diagonal lines used for depicting the crawling pangolin on top of the spout and the dramatic projection of several creatures—the crying goat leaping out of the makara’s mouth and the giant boar jumping out of the group—create animated movement. When the king and members of the royal family came here for bathing, they must have enjoyed the art because all the creatures appeared to be so realistic, but they also undoubtedly appreciated the effect of the large volume of water constantly gushing with resonant sound creating a relaxing, eternal monsoonal phenomenon.

For recent scholarship, see Raimund O.A. Becker-Ritterspach, Water Conduits in the Kathmandu Valley (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1995); Sukra Sagar Shrestha, “Tusa Hiti,” Ancient Nepal: Journal of the Department of Archaeology 139 (1996): 1–10; Gudrun Bühnemann, “17th Century Tantric Iconography of Nepal: New Research on the ‘Royal Bath’ in Patan,” Orientations 39, no. 6 (September) (2008): 88–95; Gautama V. Vajracharya, “The Creatures of the Rain Rivers, Cloud Lakes: Newars Saw Them, So Did Ancient India,” Asianart.com, January 7, 2009, https://www.asianart.com/articles/rainrivers/index.html; Gautama V. Vajracharya, “Sculpted Spouts of Nepalese Fountains and Vedic Evidence: Dolphin Deified—A Review Article,” Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 25, no. 3 (2020): 1–23.

Satyamohan Joshi, Nepali Kalako Ruparekha (An Outline of Nepalese Art) (Kathmandu: BookArt Nepal, 2016), 331.

Thanks to Kerry Lucinda Brown for identifying the creature as a pangolin.

An ancient Indian collection of hymns, the earliest Sanskrit text, composed around the fifteenth century BCE.

Gautama V. Vajracharya, “Nepal Samvat and Vikrama Samvat: Discerning Original Significance,” Asianart.com, November 6, 2018, https://www.asianart.com/articles/gvv-lecture/index.html.

Gautama V. Vajracharya, Frog Hymns and Rain Babies: Monsoon Culture and the Art of Ancient South Asia (Mumbai: Marg Foundation, 2013), 130.

Gautama V. Vajracharya, “Sculpted Spouts of Nepalese Fountains and Vedic Evidence: Dolphin Deified—A Review Article,” Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 25, no. 3 (2020): 12.

Gautama V. Vajracharya, Frog Hymns and Rain Babies: Monsoon Culture and the Art of Ancient South Asia (Mumbai: Marg Foundation, 2013), 134–38.

Gautama V. Vajracharya, Frog Hymns and Rain Babies: Monsoon Culture and the Art of Ancient South Asia (Mumbai: Marg Foundation, 2013), 134–38.

Mary Shepherd Slusser, Art and Culture of Nepal: Selected Papers (Kathmandu: Mandala Publication, 2005), 161–68.

Vajracharya, Gautama V. 2016. Nepalese Seasons: Rain and Ritual. Exhibition catalog. New York: Rubin Museum of Art. https://issuu.com/rmanyc/docs/nepalase_seasons_-_combo-_96_ppi

Gautama V. Vajracharya, “Golden Fountain of Bhaktapur: Architectural Expression of Monsoonal Phenomena,” Project Himalayan Art, Rubin Museum of Art, 2023, http://rubinmuseum.org/projecthimalayanart/essays/golden-fountain-of-bhaktapur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Cum nihil placeat pariatur deserunt eius ullam incidunt maxime sunt ipsam. Ipsa, provident, laudantium, rem assumenda laboriosam veniam autem voluptas sint officia distinctio enim aut explicabo fuga animi voluptatum earum recusandae excepturi atque dignissimos iste? Exercitationem, praesentium eum. Harum ut maiores expedita exercitationem perspiciatis soluta aperiam dolores natus unde, sequi vitae debitis ex aliquam quas eum reprehenderit esse. Cumque amet et earum necessitatibus, repellendus ullam ducimus corporis architecto culpa placeat eum odit cum iure illo vitae rerum! Ullam et suscipit culpa? Eos voluptatum laudantium iste vero impedit adipisci maxime magni natus voluptatibus.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.