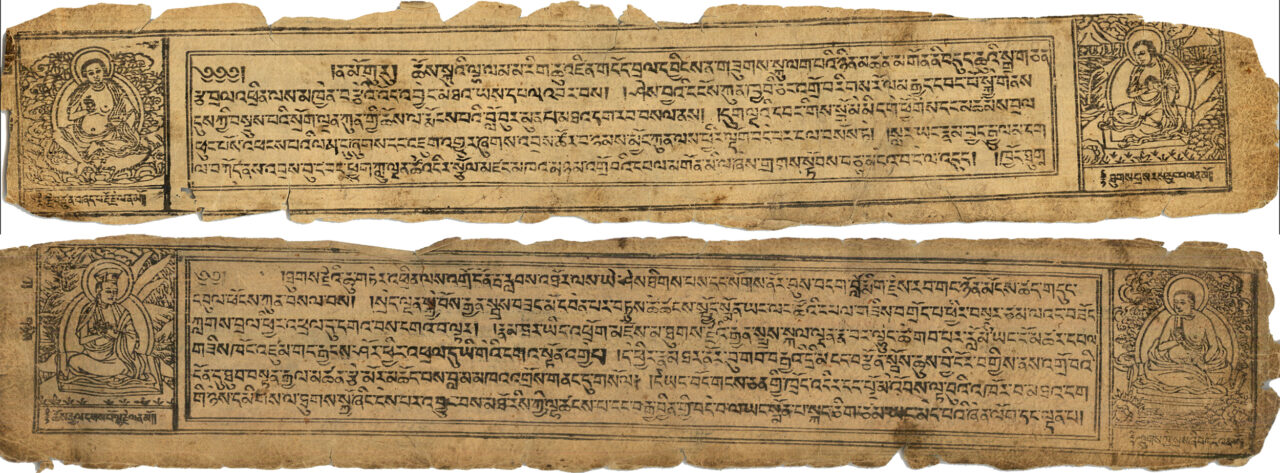

The Cultural Revolution was a political and social movement in communist China from 1966 to 1976. During this time, traditional culture across all of China came under violent attack, and almost all religious institutions were shut down and many were physically destroyed. In minority areas, ethnic differences and indigenous cultural practices, such as use of Tibetan language or dress, were seen as backward and subject to persecution, adding an additional racial dimension. Hundreds of thousands of Tibetans fled to India or Nepal, and many Himalayan artworks were destroyed or scattered abroad.

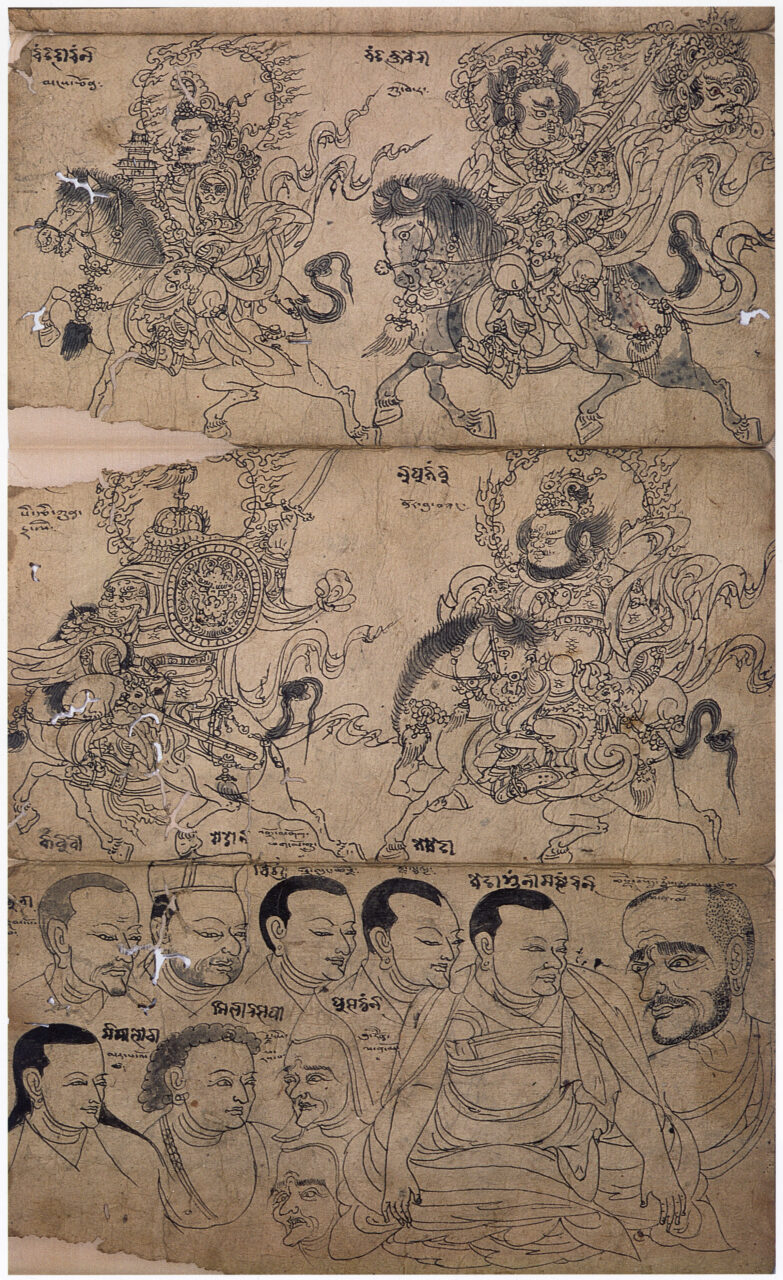

The Geluk are the most recent of the major “Later Diffusion” traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. Founded on the teachings of Tsongkhapa (1357–1419 CE) and his students, the Geluk are known for their emphasis on monastic discipline and the scholastic study of Mahayana philosophy, especially Madhyamaka. In the seventeenth century the Geluk supporting the Dalai Lamas became the largest and most powerful Buddhist tradition in both Tibet and Mongolia, where city-sized Geluk monasteries and their satellites proliferated widely. For long periods, Geluk monks effectively ruled both countries in dual-rulership or priest-patron political systems. A follower of the Geluk is called a Gelukpa.

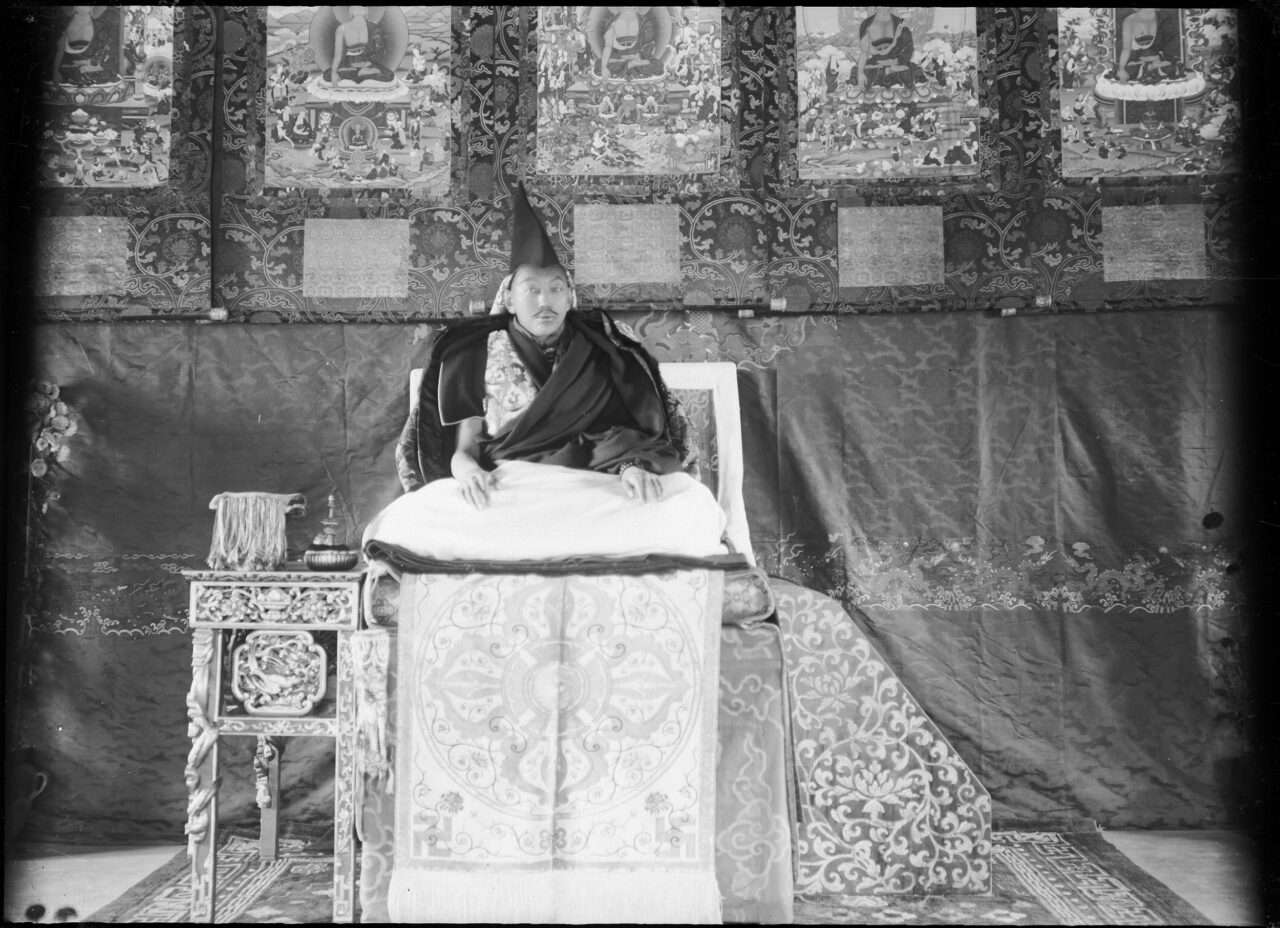

In the Tibetan Buddhist and Bon traditions, “lama” is a term of respect for a high monk or religious teacher, often a monastery abbot or a tulku. The Sanskrit equivalent is “guru,” meaning “venerable one” or “teacher.” In some traditions, like the Kagyu, lama is also a person who has completed a three-year retreat practice.

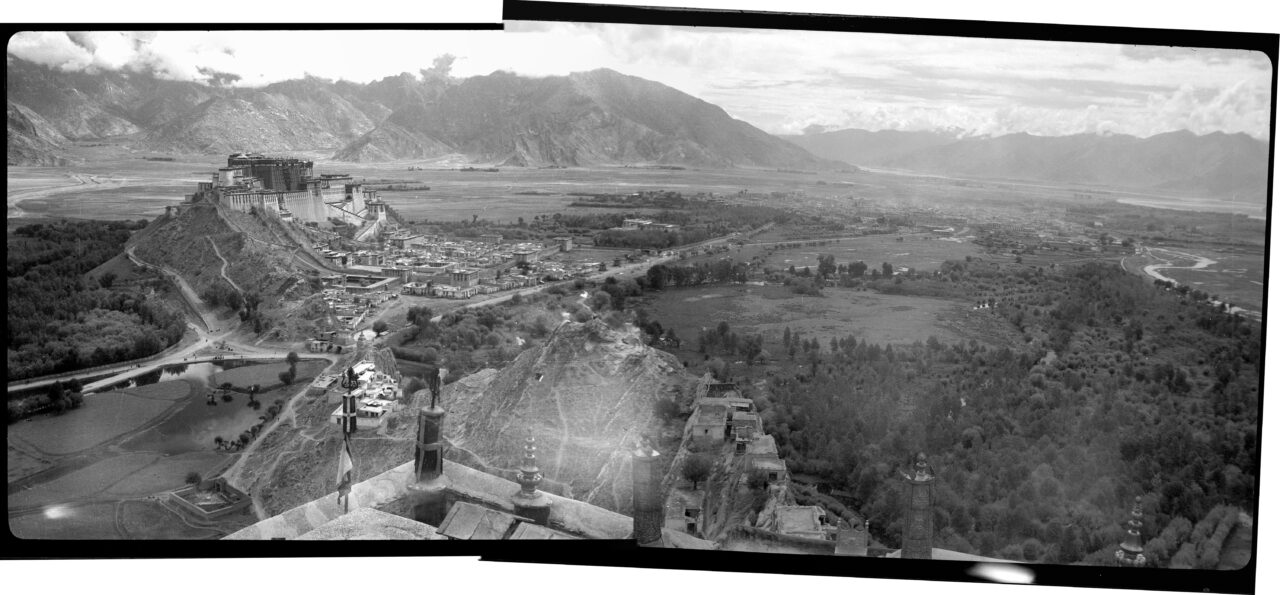

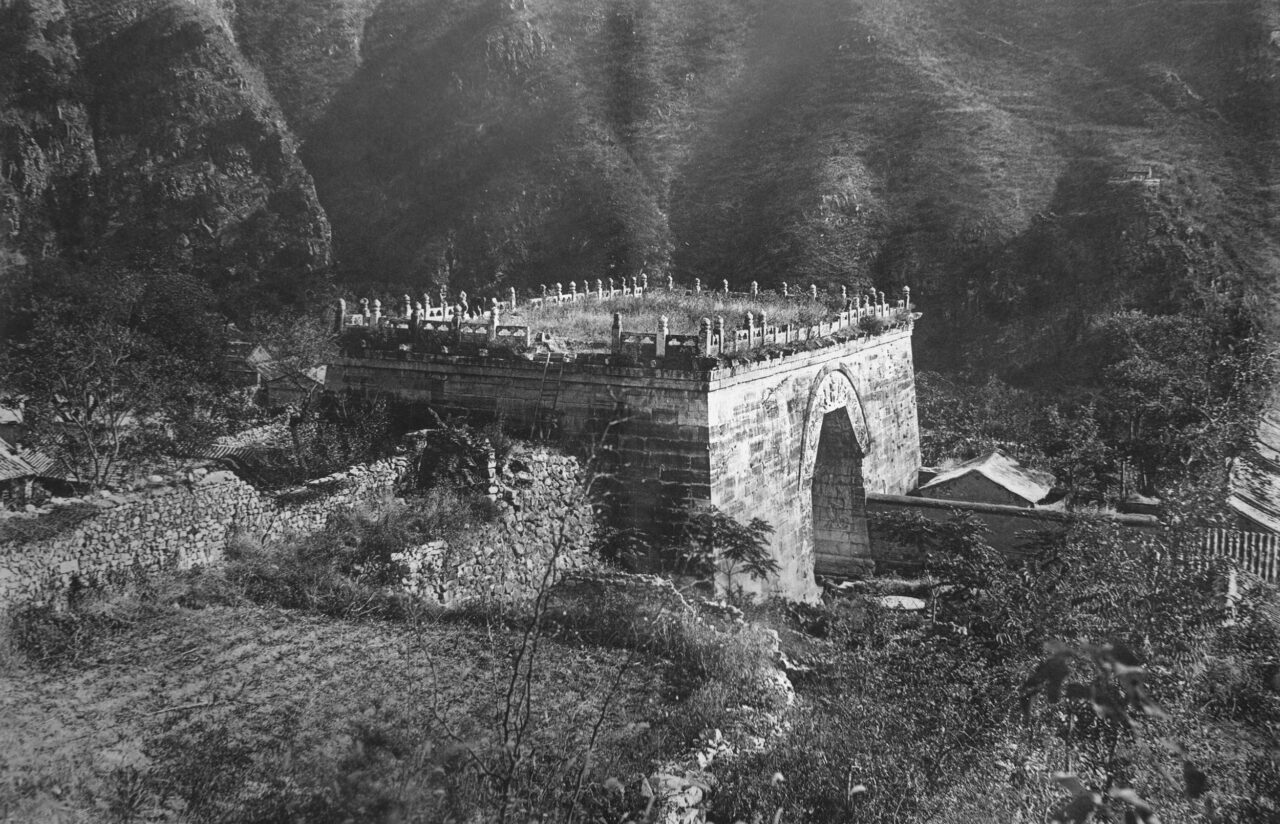

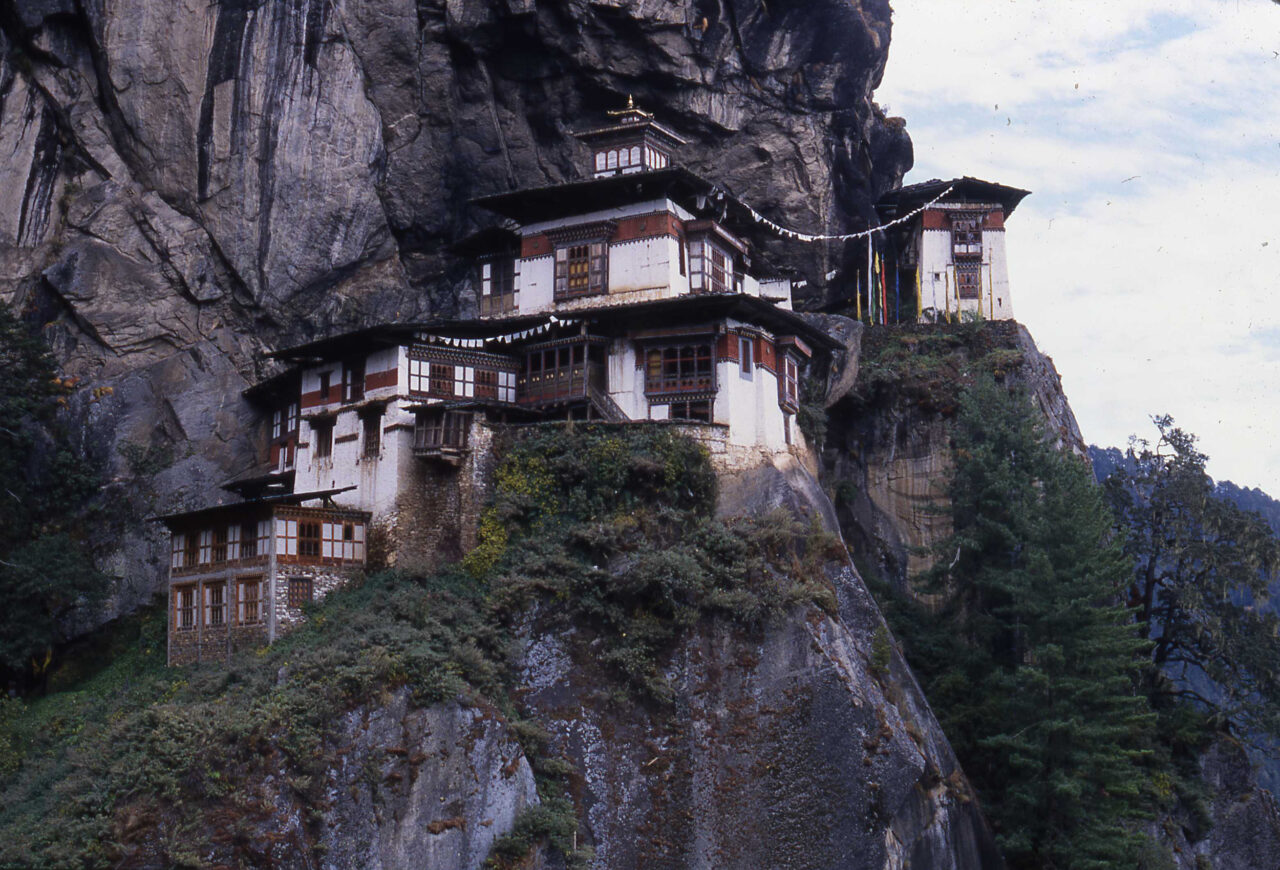

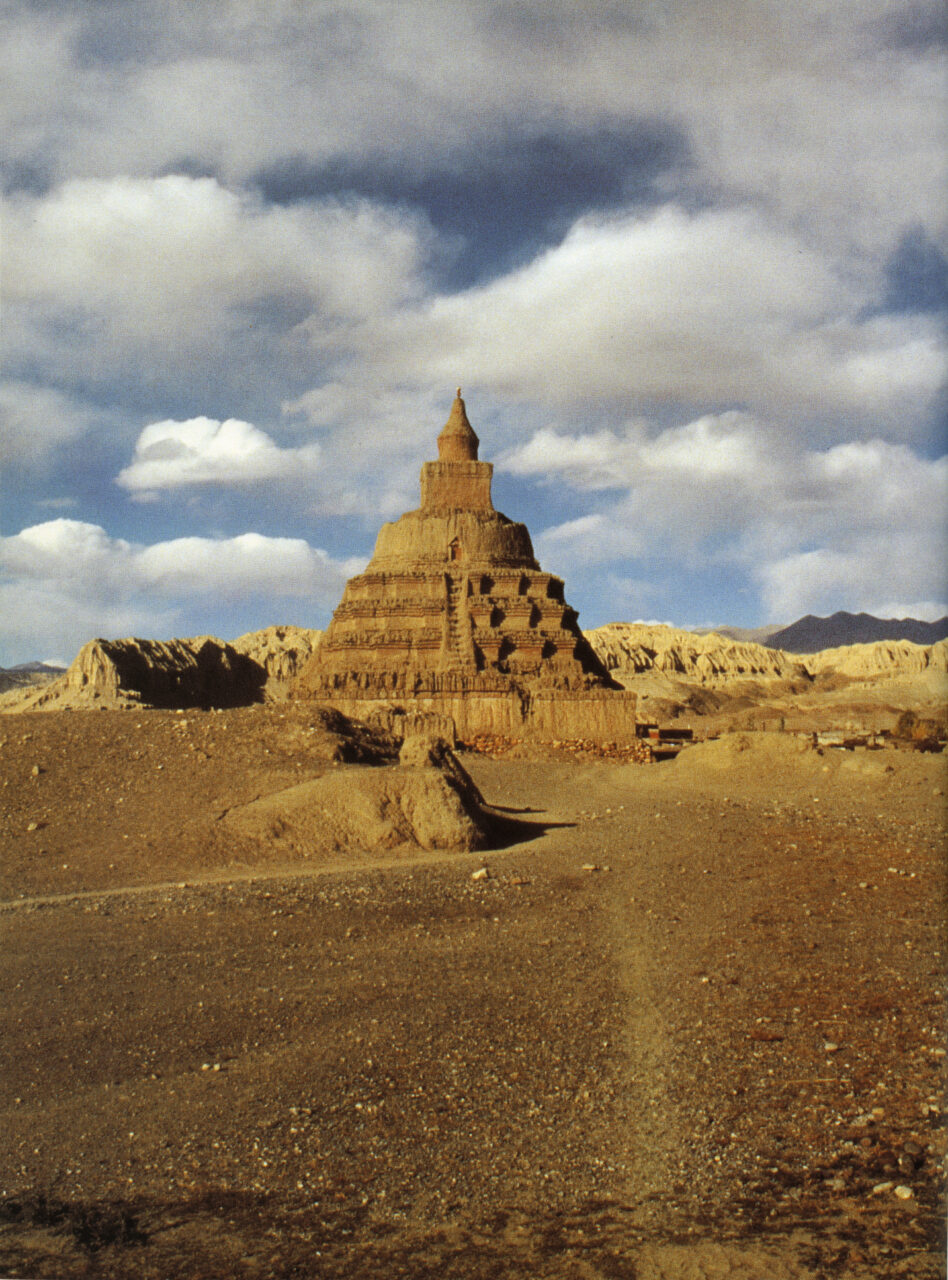

A monastery is a place where monks live, study, and perform ritual. It includes temples and other structures. Monasteries are central to Buddhism, and are also important in Bon, Hinduism, and Daoism. In Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian areas, some monasteries are enormous, wealthy, and powerful institutions, with branches of satellite monasteries forming networks across regions, often with thousands of monks, many decorated chapels, and huge holdings of land. Other monasteries, called hermitages, can be extremely simple, little more than a cave where hermits meditate. Generally, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery will have an assembly hall, several temples (Tib. lhakhang) for worship of specific deities, a protector chapel, as well as monks’ accommodations. A related institution in Newar Buddhism are the baha and bahi.

Pakmodru is a monastery in south-central Tibet, as well as a branch of the Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism associated with this monastery. The leader of Pakmodru, Changchup Gyeltsen (1302–1364), was able to take control of central Tibet in 1354, thus ending the hegemony of the Mongol Empire and the Sakya tradition in the Himalayas. The power of the Pakmodru faded due to internal conflicts in the fifteenth century.

Sakya is the name of a monastery and of a major tradition of Tibetan Buddhism that originated there during the Later Diffusion of Buddhism. Sakya Monastery was the seat of power during Sakya-Mongol rule in Tibet (1260–1350s), founded on the priest-patron relationship. Notable Sakya figures include Sakya Pandita (1182–1251), who played an instrumental role in establishing Tibetan relations with the Mongols; Drogon Chogyel Pakpa (1234-1280), who served as Qubilai Khan’s imperial preceptor and invented the Pakpa Script; and Buton (1290–1364), who compiled the Tibetan Canon. The Sakya are particularly known for their Lamdre teachings. In the 1350s, Pakmodru replaced the Sakya political prominence.