Taktsang, the Tiger’s Lair

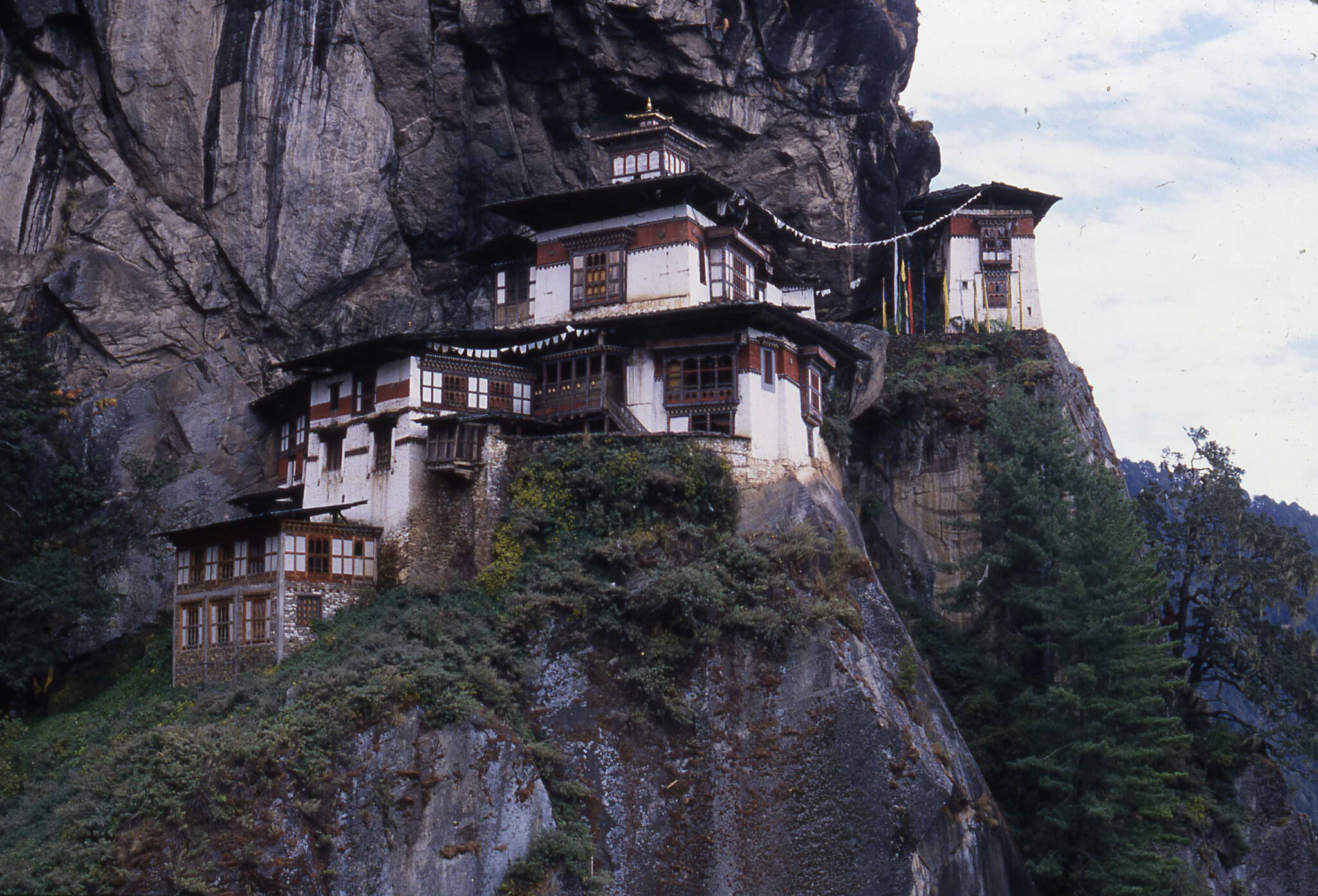

Paro District, western Bhutan founded 1692–1694Taktsang Lhakhang; Upper Paro Valley, western Bhutan; constructed 1692–1694 by command of Desi Tenzin Rabgye (1638–1696); photograph ©John A. Ardussi, 1995

Bhutan’s Most Acclaimed Religious Sanctuary

Taktsang Lhakhang; Upper Paro Valley, western Bhutan; constructed 1692–1694 by command of Desi Tenzin Rabgye (1638–1696); photograph ©John A. Ardussi, 1995

Taktsang Lhakhang; Upper Paro Valley, western Bhutan; constructed 1692–1694 by command of Desi Tenzin Rabgye (1638–1696); photograph ©John A. Ardussi, 1995

Scholar John Ardussi introduces Bhutan’s most recognizable monument, the spectacular cliffside shrine known as the “The Tiger’s Lair.” Legends say that the legendary Indian Buddhist master Padmasambhava flew here on a tiger’s back to subdue local demons. Monks from Tibet began to meditate here in the sixteenth century, and the temple was built from 1692 to 1694 by the nephew of Bhutan’s national founder. The murals inside were damaged in a 1998 fire, and today scholars use old photographs to study them.

The Eight Manifestations of Padmasambhava are eight names of the legendary tantric master and yogin, who became known when he defeated the hostile spirits of Tibet while converting the land and its gods to Buddhism. The names became standardized and assumed iconographic forms now known as the Eight Manifestations of the Guru. Different texts give varied lists of these manifestations.

The Kagyu are a major Later Diffusion tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. The Kagyu trace their lineages back to the Mahasiddhas, the great tantric masters of medieval India. The Kagyu are known for their yogic practices, as well as the teaching of Mahamudra, or the “Great Seal.” The Kagyu tradition includes many different branches, such as the Karma, Drukpa, Drigung, Tselpa, Pakmodru, and others. The most influential leaders of the Karma Kagyu are the Karmapas, a tulku lineage associated with that Kagyu branch. In Bhutan, the Drukpa Kagyu tradition serves as the state religion. A follower of the Kagyu is called a Kagyupa.

Meditation is a central practice of many Asian religious traditions, including Hinduism, Buddhism, Bon, and Daoism. There are many forms of meditation. One kind of meditation involves clearing the mind, focusing on breathing, and generating feelings of compassion towards all living beings. Other types of meditation involve concentrating on and internalizing philosophical concepts. In Vajrayana Buddhism, an important type of meditation practice is visualization, such as deity-yoga, in which the meditator visualizes themselves becoming the deity, aspiring to take on their enlightened qualities while performing ritual activities.

The Nyingma are a tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. The Nyingma trace their lineages back to the first introduction of Buddhism into the Himalayas in the time of the Tibetan Empire, most importantly to the legendary Indian yogin Padmasambhava. The Nyingma are known for their “treasure revealers” (Tib. terton), lamas who travel the Himalayas, revealing ritual texts, objects, and hidden lands thought to be concealed within the Tibetan landscape. The Nyingma are also famed for the Dzogchen teachings, a set of meditative practices focused on the bardo states, and the nature of the mind as pure, self-arising consciousness. Unlike other Buddhist traditions, many Nyingma practitioners are not celibate and can marry, raise families, and grant Vajrayana initiations and teachings to their children.

In Hinduism, Buddhism, and Bon, some gods and deities are shown with flaming hair, bulging eyes, mouths showing fangs, adorned with garlands of severed heads, and trampling enemies, real or metaphorical. In Tantric Buddhism, such deities are said to be wrathful manifestations of wisdom and method who assume fierce appearance to protect, remove or overcome mental afflictions blocking the path to enlightenment. Others are unenlightened, indigenous gods bound by oath to protect Buddhist traditions. Some female deities, or dakinis, like Vajrayogini, appear as semi-wrathful, in beatific form but bearing small fangs. In the Bon tradition, similarly to Tibetan Buddhism, wrathful deities can be emanations or represent local gods and sprits. In Hindu traditions, gods and goddesses can appear fierce, holding many weapons meant to overcome demons.

Ten miles north of modern Bhutan’s Paro Airport can be found Taktsang (Taktshang), “The Tiger’s Lair,” one of the most profoundly spiritual Himalayan temples known from early Tibetan Buddhist lore. Prior to a destructive fire of 1998, the original Taktsang temple complex dating from the late seventeenth century was ledged across a massive cliff, along an ancient pilgrimage and trade route connecting Tibet with India. Traders and pilgrims from Tibet would have crossed into Bhutan at , descending a narrow, rocky gorge opening into the forested valleys of upper Paro Valley, where soon they would encounter on their left the dramatic cliffs of Taktsang.

The early history of Taktsang is clouded in legend. Its famous cliffside caves host sites where Buddhist revelation texts called treasure literature were allegedly first deposited during the ninth century and later recovered by treasure revealers, or terton. The most famous are Lion Cave, or Sengge Phug, and Splendor Cave, or Palphug.

The most prominent religious figure associated with Taktsang is the legendary Indian master Padmasambhava, the “Lotus-born” Guru Rinpoche (eighth–ninth century), revered as the bringer of Tantric from India to Tibet and Bhutan. His twelfth-century biography Namtar zanglingma (The Copper Island Biography), attributed to the Tibetan historian Nyangrel Nyima Wozer (1124–1192), is the earliest text dealing with his life. Consistent with his persona, Padmasambhava’s dual motivation was the conquest of local deities opposed to Buddhism, and meditation in sacred spaces controlled by them, including Taktsang and other ancient sites along the Himalayas. Reflecting this tradition is the popular story that Padmasambhava flew to Taktsang riding on the back of a tiger, a theme often rendered in artistic works. It was the eighth and last of his ritualistic manifestations, that of Dorje Drolo, a fierce aspect in which Padmasambhava rides on the back of a tiger, defeating enemies of the Buddhist Dharma (fig. 2).

Mural of Guru Rinpoche (Guru Dorje Dolo) riding on tigress; Taktsang, Paro District/Paro Valley, Bhutan; ca. late 17th–early 18th century; photograph © Jürgen Schick, courtesy the John C. and Susan L. Huntington Photographic Archive of Buddhist and Asian Art (32684)

The story of Taktsang shifts from the ninth to later centuries. Nyangrel’s accounts of Taktsang’s caves induced later generations of Tibetan monks to follow the clues in his writings, in search of meditation sites and Buddhist texts said to have been hidden in the Tibetan southlands during Tibet’s royal dynastic era from the eighth to the ninth century.

The earliest datable monasteries in the Taktsang complex are located not on the face of the cliff, however, but on the ridge above, where they were founded in the sixteenth century by and Katok monks from eastern Tibet. These include Orgyen Tsemo and Zangdok Pelri. From the fifteenth to the seventeenth century, monks from these affiliated monasteries, and other Drukpa monasteries on the valley floor, jointly cared for the sacred meditation cave sites on the cliff itself. From this pre-seventeenth-century era can also be tentatively dated a Buddhist painting on the rock wall where Taktsang is now located (fig. 3), before the painting’s destruction in the tragic 1998 fire.

Rock Painting (no longer extant); Taktsang, Upper Paro Valley, western Bhutan; ca. 14th–15th century; photograph by Brian Shaw, 1980, courtesy Brian & Felicity Shaw Photo Archive, Centre for Bhutan Studies, Thimphu (bcs 1980 0404 [324])

The famous Taktsang Lhakhang that we see today, clinging to the face of the cliff, was originally constructed in 1692–1694 by the Fourth Druk Desi or civil ruler of Bhutan, Tenzin Rabgye (r. 1680–1694). He was a nephew of the founder of the Bhutan state, Zhabdrung Rinpoche Ngawang Namgyel (1594–1651), at whose behest the temple was constructed (fig. 4). As reflected in its artworks and legendary history, Taktsang represents a fusion in Bhutan of Kagyu and Nyingma sectarian traditions that continues to this day. Tenzin Rabgye came to be revered both as heir to the Zhabdrung’s Drukpa doctrinal and family legacy, and as a re-embodiment of Padmasambhava.

Zhabdrung Rinpoche Ngawang Namgyel (1594–1651?); second-floor hallway, Tango Monastery; 17th century (1688/90); pigment on canvas; photograph by Tashi Lhendup (Bhutan Ministry of Culture)

In the same year as Taktsang’s founding, Tenzin Rabgye staged the first-ever enactment at Paro of Tshechu or “tenth-day” rites and public festivities honoring Padmasambhava, following an inaugural performance two years earlier at the Bhutanese capital in Thimphu. Tshechu is typically staged as a three-day monastic prayer event, ending with the public performance of costumed dances by monk-actors, overseen by a prominent monk garbed as Padmasambhava. For the Paro performance in 1692, Tenzin Rabgye himself led the ceremonies while standing at the entrance of Palphug Cave on the cliffside above. Culminating his performance, auspicious omens are said to have appeared in the sky, visible to the crowd of spectators on the valley floor below. The detailed account of these events was recorded by an eyewitness, Tenzin Rabgye’s biographer, the Sixth Je Khenpo of Bhutan Ngawang Lhundrub (1670–1730).

The original mural artwork within Taktsang was created by Bhutanese students of the Tibetan master artist Tsang Khenchen (1610–1684), who took refuge in seventeenth-century Bhutan during the later years of Zhabdrung Rinpoche, faced with sectarian opposition from the emergent government of the Fifth Dalai Lama. He was a master of the so-called Tsangri and styles of painting, which he studied in Tibet under the Tenth Karmapa Hierarch, Choying Dorje (1604–1674), who was also an acknowledged artist. Tsang Khenchen spent many years in Bhutan, where he trained a group of talented art students. Thus, the chief artisan assigned by Tenzin Rabgye to lead the Taktsang project was a Bhutanese monk named Drakpa Gyatso (1646–1719), Tsang Khenchen’s most accomplished student. Drakpa Gyatso’s autobiography describes in some detail how the work proceeded. Complementary information is found in the catalog of the 1688–1690 renovation of Tango Monastery, another major restoration sponsored by Tenzin Rabgye, which names the artists and lists all the murals and sculptures on each floor and wall of the building that were part of the project.

Taktsang is actually a series of connected sanctuaries on the same cliff, several of which enclose the ancient meditation caves referred to earlier. Although there exists no contemporary catalog for Taktsang similar to that of Tango, a few scholars of Himalayan art were permitted by Bhutanese authorities to photograph several of Taktsang’s temples, in the years prior to the 1998 fire. Based on style and level of artistry, we can with some certainty date many of the murals to the seventeenth century, and perhaps personally to the founding work of Drakpa Gyatso and other artists trained by Tsang Khenchen.

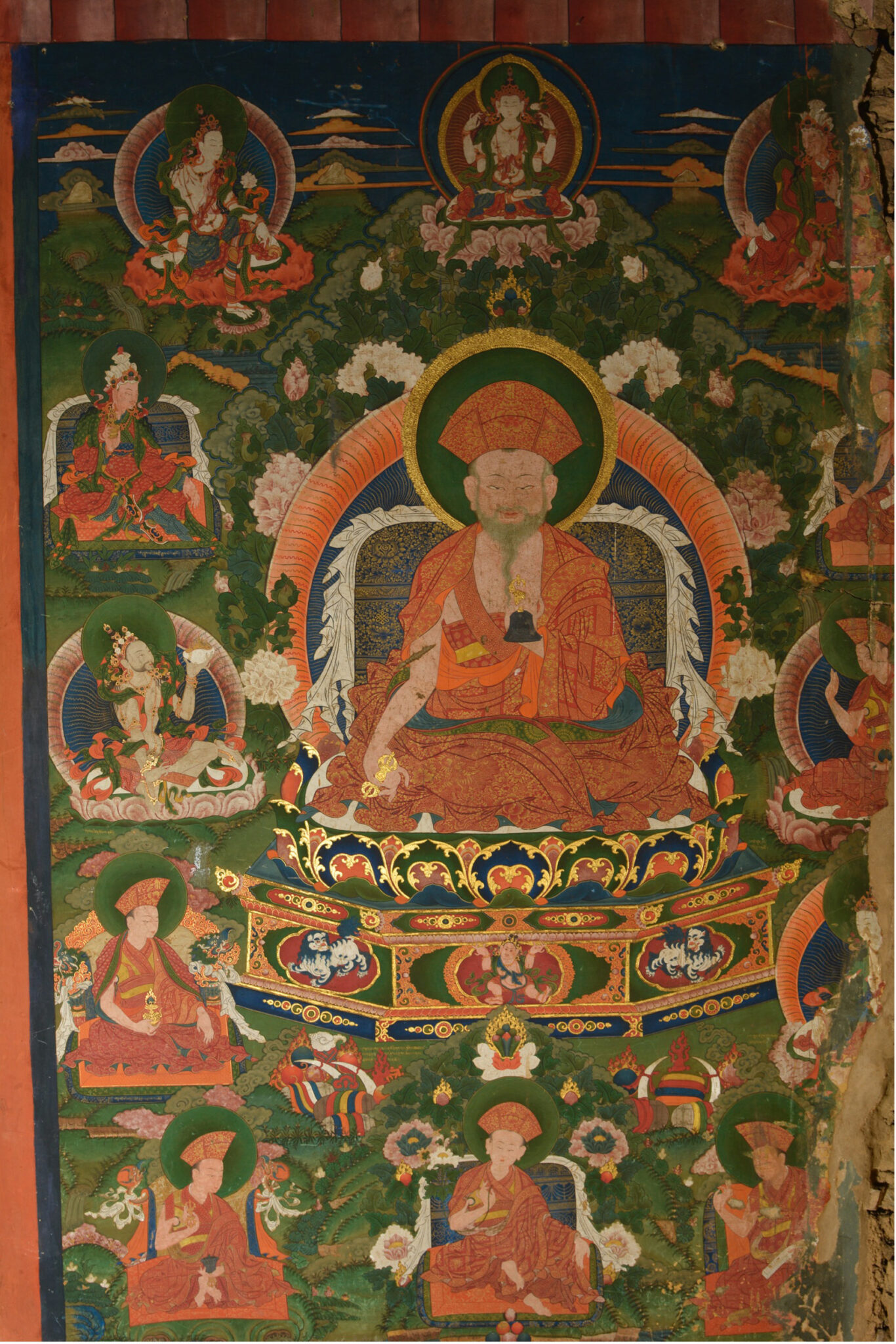

Whereas most of the Tango murals focus on members of the Drukpa lineage of Zhabdrung Rinpoche and Tenzin Rabgye, Taktsang is principally a shrine to Padmasambhava in his eight manifestations, first enumerated in historical works from the era of Nyangrel Nyima Wozer. The main Taktsang temple is itself named Guru Tsengye Lhakhang, “The Temple of the Guru with Eight Names.” The central portion of a vast mural from the upper level of Taktsang illustrates the main image of Padmasambhava seated on a throne within his celestial and worldly realm. He is surrounded by other images of himself, his attendants, worshippers, and fierce protectors of the dharma.

We are fortunate to have photographs of the Padmasambhava mural taken separately by two European visitors, Jürgen Schick (figs. 5, 6, and 7) and Brian Shaw (fig. 8). The Huntington Archive of Buddhist and Asian Art at Ohio State University is the repository for over four hundred digital images of artwork from Bhutan, including a collection of fifty-three photographs taken at Taktsang circa 1980 by the German scholar Jürgen Schick. The images come from different areas within the temple complex. By careful comparison, we now know that some are close-up photos of sections from the same mural, a fact not explained in Schick’s notes, but which can be confirmed by comparison with an image taken by Brian Shaw (fig. 5 appears on the far right in the middle of fig. 8 and fig. 2 is right below it). For example, Schick scan no. 35528 is actually a portion of the mural shown in scan no. 32888.

Guru Rinpoche / Padmasambhava Blessing Devotees with Purifying Flame; Taktsang Monastery; ca. 1692–1693 (destroyed in 1998 fire); pigment on canvas; photograph © Jürgen Schick, courtesy the John C. and Susan L. Huntington Photographic Archive of Buddhist and Asian Art (35528)

Guru Rinpoche / Padmasambhava Battling Ferocious Animals; Taktsang Monastery; ca. 1692–1693 (destroyed in 1998 fire); pigment on canvas; photograph © Jürgen Schick, courtesy the John C. and Susan L. Huntington Photographic Archive of Buddhist and Asian Art (35530)

Guru Rinpoche / Padmasambhava; Taktsang Monastery; ca. 1692–93 (destroyed in 1998 fire); pigment on canvas; photograph © Jürgen Schick, courtesy the John C. and Susan L. Huntington Photographic Archive of Buddhist and Asian Art (35531)

Detail of Padmasambhava Mural, showing central portion; Taktsang, Upper Paro Valley, western Bhutan; ca. 1692–93; pigment on canvas; photograph by Brian Shaw, 1980, courtesy Brian & Felicity Shaw Photo Archive, Centre for Bhutan Studies, Thimphu (bcs 1980 0404 [323])

The close-up photos by Schick are high enough in resolution to reveal several important inscriptions in Tibetan. For example, scan no. 35528 bears a legend in Tibetan, Pema Gyelpo (Tibetan: pad ma rgyal po), “The Lotus King,” one of the Eight Manifestations of Padmasambhava (fig. 5). Other scenes in Schick’s photos bear Tibetan legends describing the physical location where Padmasambhava taught (fig. 7).

There is clearly more opportunity to analyze the surviving artworks of Taktsang. Once the murals being restored at Tango are available for academic study, art specialists will be in a better position to compare them with those from Taktsang (figs. 4, 9-13). A common thread connecting them is the person of Gyelse Tenzin Rabgye, who recruited the artists trained under Tsang Khenchen, who brought his artistic skills from Tibet to Bhutan. A significant portion of Tenzin Rabgye’s biography describes temple restorations that he sponsored, showing his devotion to the painting, sculpture, and spiritual dance traditions of Bhutan.

Guru Rinpoche; second floor hallway, Tango Monastery; 17th century (1688/90); pigment on canvas; photograph by Tashi Lhendup (Bhutan Ministry of Culture)

Saint Drukpa Kunley, great-grandfather of Desi Tenzin Rabgye; second floor, Desi Zimkhang, Tango Monastery; 17th century (1688/90); pigment on canvas; photograph by Shuzo Uemoto (Honolulu Academy of Arts)

Guru Rinpoche / Padmasambhava; Taktsang Monastery, upper Lhakhang, Upper Paro Valley, western Bhutan; ca. 1692–93 (destroyed in 1998 fire); pigment on canvas; photograph © Jürgen Schick, courtesy the John C. and Susan L. Huntington Photographic Archive of Buddhist and Asian Art (32888)

The classic work on the Eight Manifestations (mtshan brgyad) is the Pema Thangyik [Lotus Chronicle]. A mandala of these eight manifestations was once painted inside the Taktsang temple, which was destroyed by fire in 1998, and in many other locales. For background on Padmasambhava and earlier versions of the theme, see Daniel A. Hirshberg, Remembering the Lotus-Born: Padmasambhava in the History of Tibet’s Golden Age (Somerville, MA: Wisdom, 2016).

See Benjamin Bogin and Andrew Quintman, eds., “Redacting Sacred Landscape in Nepal: The Vicissitudes of Yolmo’s Tiger Cave Lion Fortress,” in Himalayan Passages: Tibetan and Newar Studies in Honor of Hubert Decleer, trans. Andrew Quintman (Boston: Wisdom, 2014), 69–95, 81–83, for details on several of these monks, including Kathok Sonam Gyeltsen (KaH thog bsod nams rgyal mtshan), though possibly not the Tibetan mystic Milarepa.

A complete translation of the account, presented in Tenzin Rabgye’s Tibetan biography, is in John A. Ardussi, “Gyalse Tenzin Rabgye and the Founding of Taktsang Lhakhang,” Journal of Bhutan Studies 1, no. 1 (1999): 36–63 and John A. Ardussi, “Gyalse Tenzin Rabgye and the Celebration of Tshechu in Bhutan,” in Written Treasures of Bhutan: Mirror of the Past and Bridge to the Future, ed. John A. Ardussi and Sonam Tobgay (Thimphu: National Library of Bhutan, 2008), 88–99.

On Tsang Khenchen’s work in Bhutan and examples from his artistic atelier, see Ariana Maki, “Tracing the Legacy of Tsang Khenchen Penden Gyatso (1610–84) in Bhutanese Art,” Orientations 3, no. May/June (2017): 108–17.

The restoration of Tango Monastery is described in some detail in John A. Ardussi, “Gyalse Tenzin Rabgye (1638-1696), Artist Ruler of 17th-Century Bhutan,” in Dragon’s Gift: The Sacred Arts of Bhutan, ed. Terese Tse Bartholomew and John Johnston, Exhibition Catalog (Honolulu and Chicago: Honolulu Academy of Arts in association with Serindia, 2008), 93–97, based on chapter 18 of Tenzin Rabgye’s biography.

There is, however, at least one entire temple wing within Tango dedicated to Guru Rinpoche, containing exquisite murals which likely date from the restoration of 1688–90. These artworks are currently being restored by trained personnel of the Bhutan Ministry of Culture, and should appear in a future exhibition.

A photograph by Jürgen Schick of the same mural can be viewed in a collection of his images at the Huntington Archive, scan no. 32888.

See “The Huntington Archive,” http://dsal.uchicago.edu/huntington/database.php.

Ardussi, John A. 1999. “Gyalse Tenzin Rabgye and the Founding of Taktsang Lhakhang.” Journal of Bhutan Studies 1, no. 1, 36–63.

Ardussi, John A. 2008a. “Gyalse Tenzin Rabgye (1638–1696), Artist Ruler of 17th-Century Bhutan.” In The Dragon’s Gift: The Sacred Arts of Bhutan, edited by Therese Tse Bartholomew and John Johnston, 88–89. Exhibition catalog. Honolulu and Chicago: Honolulu Academy of Arts in association with Serindia.

Ardussi, John A. 2008b. “Gyalse Tenzin Rabgye and the Celebration of Tshechu in Bhutan.” In Written Treasures of Bhutan: Mirror of the Past and Bridge to the Future, edited by John A. Ardussi and Sonam Tobgay, 1–24. Thimphu: National Library of Bhutan.

John A. Ardussi, “Taktsang Monastery: Bhutan’s Most Acclaimed Religious Sanctuary,” Project Himalayan Art, Rubin Museum of Art, 2023, http://rubinmuseum.org/projecthimalayanart/essays/taktsang-monastery.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Cum nihil placeat pariatur deserunt eius ullam incidunt maxime sunt ipsam. Ipsa, provident, laudantium, rem assumenda laboriosam veniam autem voluptas sint officia distinctio enim aut explicabo fuga animi voluptatum earum recusandae excepturi atque dignissimos iste? Exercitationem, praesentium eum. Harum ut maiores expedita exercitationem perspiciatis soluta aperiam dolores natus unde, sequi vitae debitis ex aliquam quas eum reprehenderit esse. Cumque amet et earum necessitatibus, repellendus ullam ducimus corporis architecto culpa placeat eum odit cum iure illo vitae rerum! Ullam et suscipit culpa? Eos voluptatum laudantium iste vero impedit adipisci maxime magni natus voluptatibus.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.