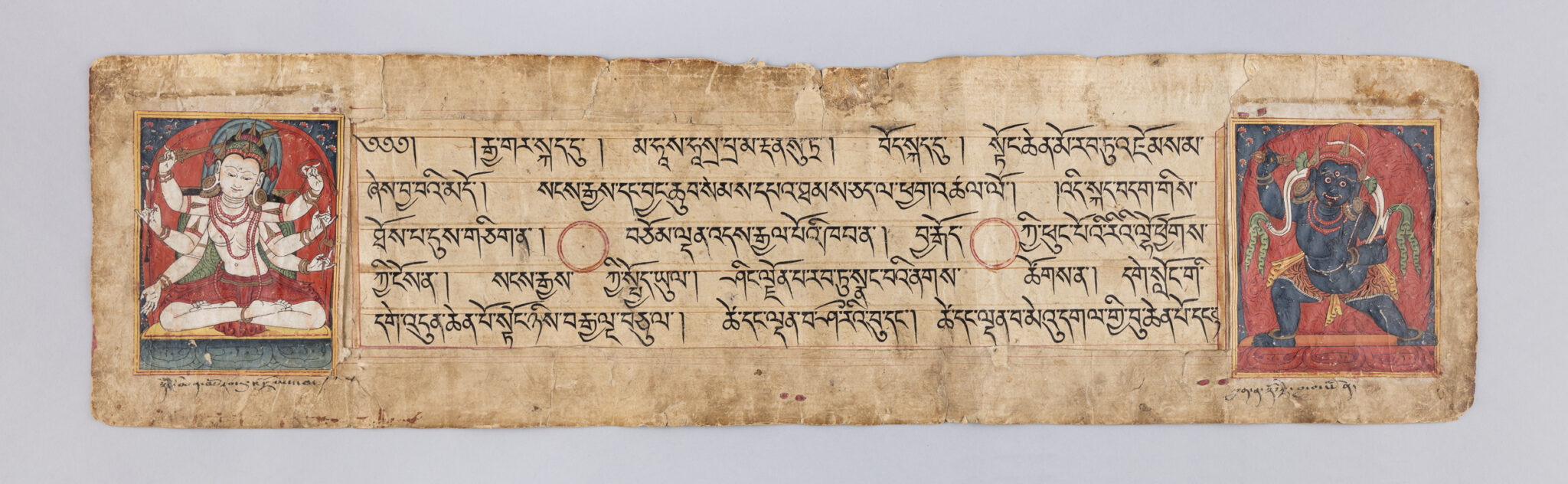

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a being who has made a vow to become a buddha or awakened. In the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, many bodhisattvas are understood as deities with enormous powers who delay their final enlightenment, remaining in the phenomenal world to help suffering beings. Among such great bodhisattvas are Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Maitreya.

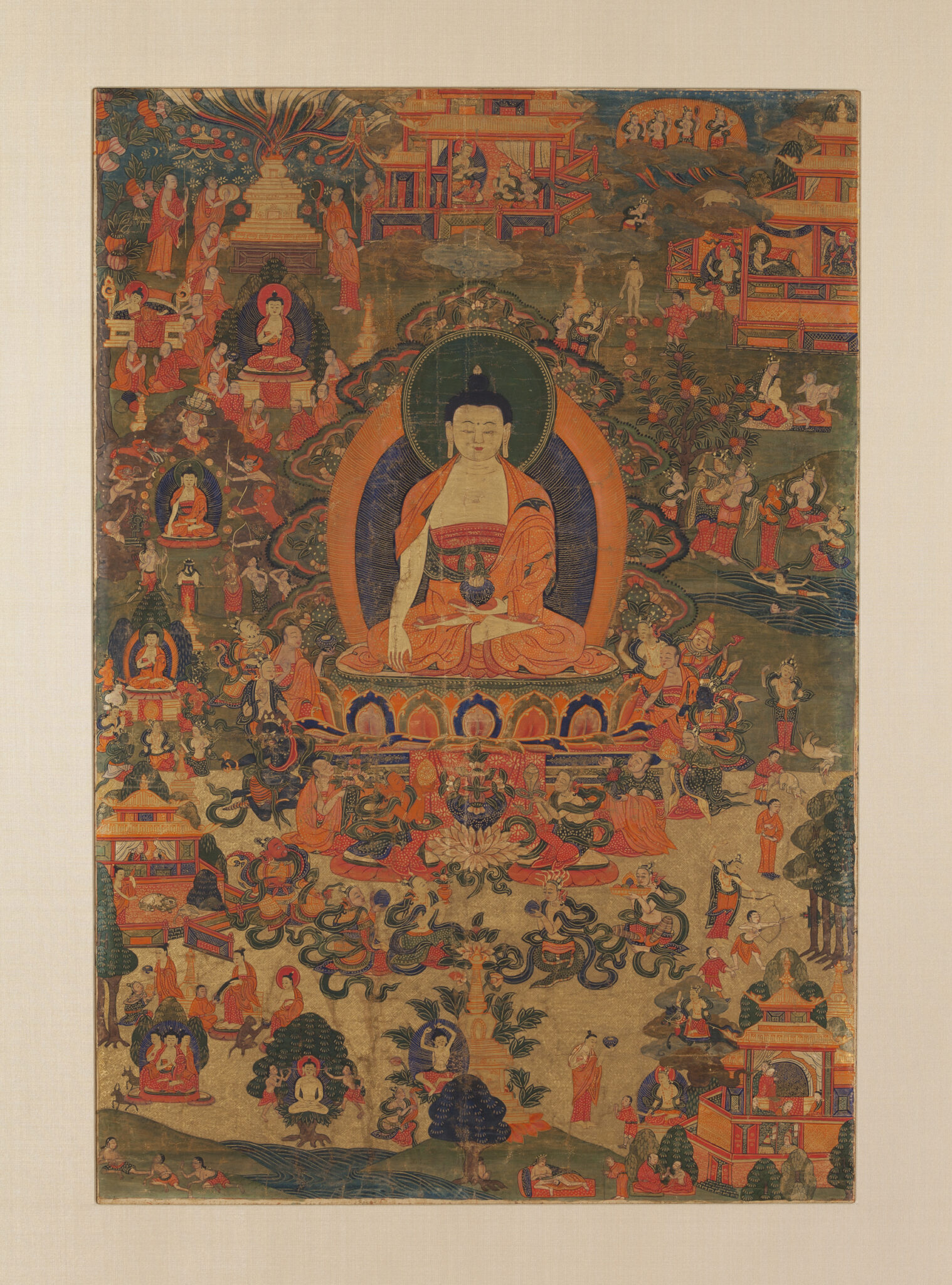

The Eight Great Events are eight scenes from the life of Buddha Shakyamuni that became a standard part of his iconography in India and Nepal. The eight events are:

- The birth of the Buddha

- His awakening (enlightenment)

- His first sermon

- A monkey offers him honey

- He tames a wild elephant

- Descending from the Heaven of the Thirty-Gods

- Defeating heretical sects by miraculous displays

- The Buddha’s death (Skt. parinirvana)

An illuminated manuscript is one that is adorned with images, designs, and decorative text. Unlike an “illustrated” text, the images in an illuminated text don’t necessarily show scenes from the story of the text.

In Buddhism, individuals become awakened or achieve enlightenment (nirvana) but continue to live out the remainder of their natural lives. They pass on into the final state at their deaths, called “parinirvana.” Most importantly, this term refers to the Buddha Shakyamuni’s parinirvana at Kushinagara when he lay down between two trees and died. The event accompanied by many miracles is one of the Eight Great Events and one of the Twelve Deeds of the Buddha’s life, and is a very common topic for Buddhist illustration.

A pothi is a traditional form of Indian book. Pothis generally have palm-leaf pages. The pages are bound along their long edge with loops of string, and then kept between wooden outer covers. Both the pages and the covers can be beautifully illuminated. Indian and Nepalese pothis were the basis for the development of Tibetan pechas, a related form of book that uses unbound paper instead of palm leaves.

Sanskrit is an ancient language used in India. An early member of the Indo-European language family, Sanskrit was the language of the ancient Vedas in the second millennium BCE. Over millennia, Sanskrit ceased to be used as a spoken language, but it continued as the main literary language of India until the modern era. The Mahayana and Vajrayana canons were originally written in Sanskrit. Today, Sanskrit continues to be studied as a liturgical language among Hindus and Newari Buddhists, and Sanskrit-language mantra and dharani are chanted in rituals all across the Buddhist world.