Mongolian Map of Capital Yekhe Khüriye

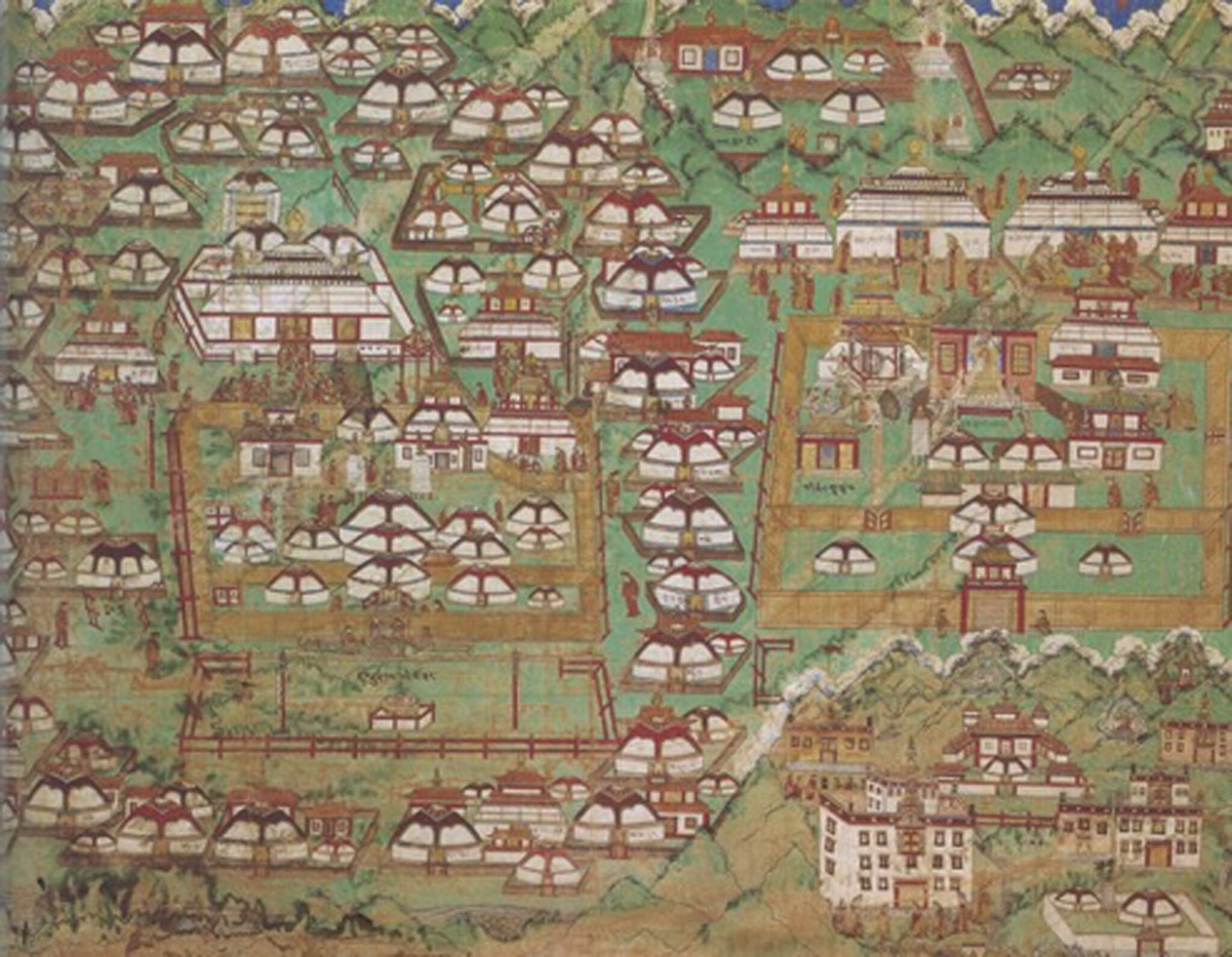

Mongolia 1912Jügdür (fl. late 19th–early 20th century); Capital Yekhe Khüriye; Mongolia; 1912; colors on cotton, 19-5/8 × 37-7/8 in. (50 × 96 cm); Bogd Khan Palace Museum, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Mapping Yekhe Khüriye’s Cityscape as the “Capital City”

Jügdür (fl. late 19th–early 20th century); Capital Yekhe Khüriye; Mongolia; 1912; colors on cotton, 19-5/8 × 37-7/8 in. (50 × 96 cm); Bogd Khan Palace Museum, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Jügdür (fl. late 19th–early 20th century); Capital Yekhe Khüriye; Mongolia; 1912; colors on cotton, 19-5/8 × 37-7/8 in. (50 × 96 cm); Bogd Khan Palace Museum, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Art historian Uranchimeg Tsultemin analyzes a painted cityscape of the nomadic monastery that later became Mongolia’s modern capital Ulaanbaatar. When the monastery settled in 1855, it soon developed into a thriving city with palaces and international commercial districts. The reincarnated Jibzundamba lama, theocratic ruler of a newly independent Mongolia, commissioned this map-like panorama of his capital as a part of a nation-building project, and a royal commission to promote the monastery as a religious and political center of Mongolia.

Dual rulership is a Tibetan political theory, in which secular and religious power are fused in the same government, similar to the Western idea of a theocracy. The Tibetan Ganden Podrang government, with the Dalai Lamas at the head, can be understood as a dual-rulership system. Dual rulership can contrast with a priest-patron or cho-yon relationship.

The Jibzundambas (from the Tibetan Jetsun dampa “venerable/reverend noble one”) were the most important lineage of tulkus in Khalkha Mongolia from 1639 to 1924, considered below only the Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas in prestige within the Geluk tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. While the Jibzundamba lineage traces its previous incarnations back to the Tibetan polymath and traveler Taranatha (1575–1634), the first formally enthroned Jibzundampa was the Mongolian prince and artist Zanabazar (1635–1723). As the Jibzundampa’s authority grew, their mobile monastery, called “the great encampment” (Mgl: yekhe khüriye), would gradually settle and develop into Mongolia’s modern capital, Ulaanbaatar. The eighth Jibzundamba ruled as khan of Mongolia from 1911 to 1924.

The Khalkha are one of the major historical subgroupings of the Mongols. Historically ruled by leaders descended from Chinggis Khan, the Khalkha inhabited a territory roughly the same as the country called Mongolia today. Other important Mongol groups after the fall of the Mongol Empire include the Chahars, who lived in what is today the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in China, the Oirat or Dzungars, who lived in Central Asia, and the Khoshut, who lived in the northern Tibetan Plateau.

A monastery is a place where monks live, study, and perform ritual. It includes temples and other structures. Monasteries are central to Buddhism, and are also important in Bon, Hinduism, and Daoism. In Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian areas, some monasteries are enormous, wealthy, and powerful institutions, with branches of satellite monasteries forming networks across regions, often with thousands of monks, many decorated chapels, and huge holdings of land. Other monasteries, called hermitages, can be extremely simple, little more than a cave where hermits meditate. Generally, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery will have an assembly hall, several temples (Tib. lhakhang) for worship of specific deities, a protector chapel, as well as monks’ accommodations. A related institution in Newar Buddhism are the baha and bahi.

A yurt, called “ger” in Mongolian, is a dome-like tent made of felt and an internal framework of wood slats used by nomads on the steppes of northern Asia. The yurt can be quickly assembled and disassembled and packed for travel and is still being used in Mongolia as a summer home.

The painting depicts the preeminent Mongolian Buddhist monastery of the Jibzundamba reincarnate rulers (Mongolian: Khutugtu). (Classical Mongolian: Yeke Küriy-e, also spelled Ikh Khüree; modern-day Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia), known to foreign visitors as Urga, is shown in a panoramic bird’s-eye view. This perspective from above is often used in depicting cityscapes and in architectural drawings in Inner and East Asia. A number of architectural representations provide specific views on the hierarchical organization of the towns. Important pilgrimage sites, such as and , received significant attention from the artists and their patrons (fig. 2). The title of this map is Capital Yekhe Khüriye, and as it was produced soon after Mongolia’s independence from the in 1911, the map was a part of a larger Mongolian nation-building project, and a royal commission to promote the Khalkha Mongolian monastery as a pilgrimage site, a religious and political center of Mongolia.

Painting of Temples and Monasteries of Lhasa; Kham region, eastern Tibet; 1900–1920; gouache on cotton, 72 3/8 × 37 7/8 in. (184.6 × 135.40 cm); Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto; The George Crofts Collection; 921.1.82; photograph courtesy the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM

Jügdür, an artist from Zoogai (monastic unit), completed the painting in 1912, as the inscription in traditional Mongolian script attached to the painting attests. Jügdür was a prominent artist, as other works by him demonstrate (fig. 3). Among his surviving works are a remarkable appliqué of and a set of paintings of three longevity deities. Jügdür was from Setsen Khan province (modern-day Khentii aimag). His fame was widespread, and he spent the last years of his life working on commissions in Tibet, where he died.

Jügdür (fl. late 19th–early 20th century); iconometrical drawing; dimensions unknown; Fine Arts Zanabazar Museum, Ulaanbaatar

The inscription clarifies that the production of the map was initiated and overseen by the Eighth Jibzundamba Bogd Gegeen (1869–1924), who was proclaimed the Bogd Khan of Mongolia on December 29, 1911:

In the second year of All-Inaugurated [1912], Lord Bogd Khan ordered Jügdür from Zoogai aimag of Züün Khüriye, who is good at and renowned for painting deities, to paint the Capital Khüriye, Gandan, and so on, the surrounding mountains, rivers, and even temples, and monasteries in the true reality of that time.

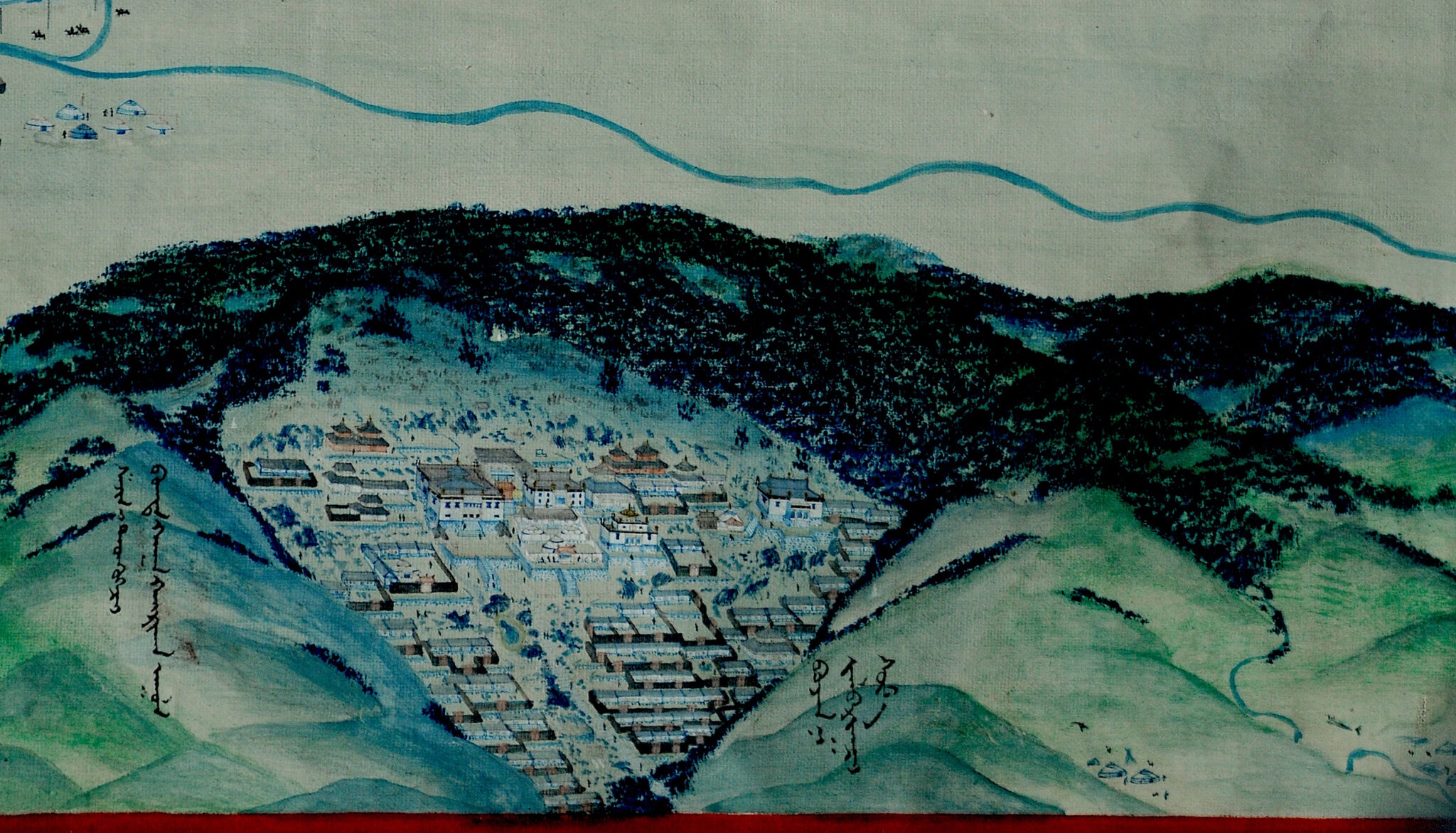

The All-Inaugurated (Mahasammata) Bogd Khan of Mongolia was both political and religious head of the new state. The theocratic government under the Bogd Khan was a fragile, young state, and as part of his state-building, the Khan initiated many projects, including translations and the reprinting of old and new texts, as well as conducting new cartographic surveys. This map was tantamount to his other projects to collect, systematize, and organize the information and knowledge, such as printing a new set of the (Kangyur), known as Urga Kangyur. There were other paintings of various parts of Yekhe Khüriye made (fig. 4), and this is the second existent map of Yekhe Khüriye. Mapping the city also contributed to the status of Yekhe Khüriye as a new pilgrimage site akin to Lhasa. Yekhe Khüriye’s abbot, Agwang Lubsang Khayidub (1779–1838), wrote several texts about of Yekhe Khüriye and a ritual of offerings to the , thereby contributing to the elevation of Yekhe Khüriye’s importance in .

Yekhe Khüriye; Mongolian; 19th century; colors on cotton, 19 5/8 × 37 7/8 in. (50 × 96 cm); Fine Arts Zanabazar Museum, Ulaanbaatar

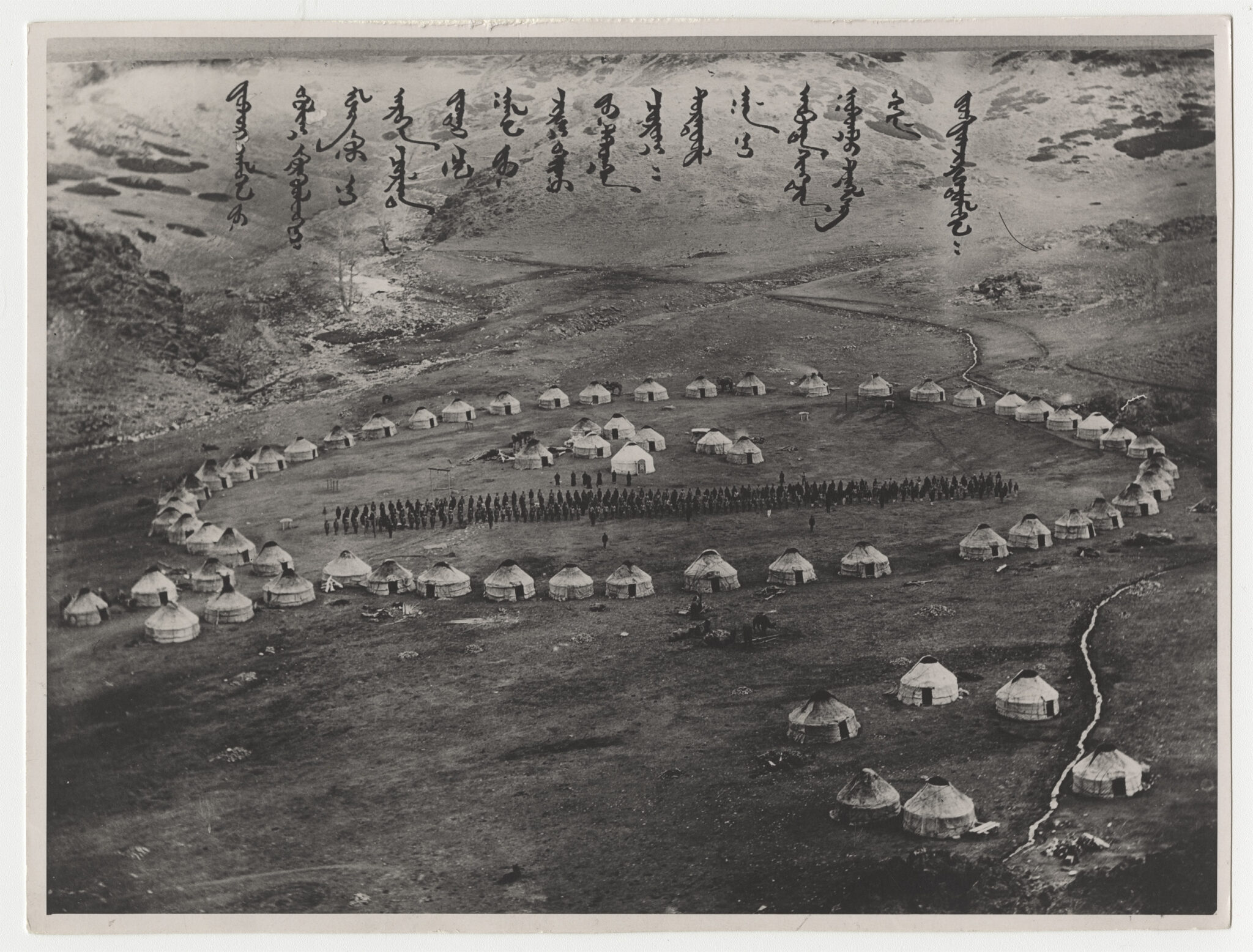

Jügdür depicts Yekhe Khüriye as a grandiose site with its two major components demarcated in the roughly elliptical arrangement of a traditional khüriye encampment. Khüriye encampments were in regular use among nomads, and the circular structure surrounding a chieftain in the center also had a purpose of defense (fig. 5). The very conception of Yekhe Khüriye begins with a (Mongolian: Örgöö or ger) which was first erected for the five-year-old Zanabazar (1635–1723) in 1639 to commemorate his enthronement as the First Jibzundamba Khutugtu. Zanabazar and the succeeding Jibzundamba Khutugtus strategically developed the Örgöö (yurt) into the monastery Yekhe Khüriye. As an encampment, Yekhe Khüriye consisted of yurts, and from its early days in the 1630s until 1855, it was fully portable and mobile, traversing long distances from the southern border to the north. As the monastery grew and expanded with new temples and increased in population, its migrations became only local, along the trade route between Russia and China. The Mongolian word “Örgöö” was rendered as “Urga” by foreign visitors.

An example of a khüriye encampment: the Torghut Prince Sin Chin Gegeen’s camp at Khara Shar, before 1927; photograph; dimensions unknown; photograph courtesy The Swedish National Museums of World Culture and Sven Hedin Foundation

The photo was given to the members of the Sino-Swedish expedition by Sin Chin Gegeen.

By the time Balgan in the nineteenth century and Jügdür in 1912 mapped Yekhe Khüriye’s holistic structure, the monastery consisted of two major and several minor parts (fig. 6). As we know from later Yekhe Khüriye writers, the large circle in Yekhe Khüriye was commonly known as Züün Khüriye (Eastern Khüriye, at center in image), and the smaller oval settlement denotes Gandan Monastery (at left). The core of Yekhe Khüriye was the Jibzundamba’s Yellow Palace, a central compound with several buildings surrounded by a yellow fence. The Yellow Palace was the place where the Jibzundamba Khutugtus resided and where their major temples once stood (fig. 7). Jügdür shows the Yellow Palace annexed by a large plaza where lay festivals (such as wrestling) and Buddhist rituals (such as tsam ritual) took place every summer. To the north of the Yellow Palace, major temples, including Bat-Tsagan (“Firmly White”) Assembly Hall (Tsogchin), Maitreya, and Dechingalba () Temples also stood (figs. 8 and 9). This nucleus of the Jibzundamba’s monastery was surrounded by thirty monastic units (aimags), where the monastic population was organized based on regional affiliation and relation to the Jibzundamba.

Balgan (act. late 19th century); Yekhe Khüriye; Mongolia, late 19th century; colors on cotton; 19 5/8 × 37 7/8 in. (50 × 96 cm); Fine Arts Zanabazar Museum, Ulaanbaatar,

Jügdür (fl. late 19th–early 20th century); Detail of Jibzundamba’s Yellow Palace, Map of Capital Yekhe Khüriye; Mongolia; 1912; colors on cotton, 19 5/8 × 37 7/8 in. (50 × 96 cm); Bogd Khan Palace Museum, Ulaanbaata

Jügdür (fl. late 19th–early 20th century); Detail of Bat-Tsagan (“Firmly White”) Assembly Hall (Tsogchin), Maitreya, and Dechingalba (Kalachakra) Temples, Map of Capital Yekhe Khüriye; Mongolia; 1912; colors on cotton, 19 5/8 × 37 7/8 in. (50 × 96 cm); Bogd Khan Palace Museum, Ulaanbaatar

Kalachakra (Dechingalba) Temple in Yekhe Khüriye Monastery; late 19th century; photograph National Central Archives of Mongolia

The second encampment, the Gandan Tegchinling Monastery (fig. 10), was built by the Fifth Jibzundamba (1815–1841) in 1838 by moving several colleges (datsans) from Züün Khüriye to the western hills, where new temples were additionally built to form a theological center named after . Gandan mirrored the Züün Khüriye in the architectural design by including a central compound with the Jibzundamba’s temples and another Zanabazar-designed Assembly Hall, all surrounded by monastic units (aimags). Yet unlike Züün Khüriye, this monastery was strictly an educational and theological center, closed and inaccessible for lay visitors, especially women and merchants.

Jügdür (fl. late 19th–early 20th century); Detail of Gandan Tegchinling Monastery, Map of Capital Yekhe Khüriye; Mongolia; 1912; colors on cotton, 19 5/8 × 37 7/8 in. (50 × 96 cm); Bogd Khan Palace Museum, Ulaanbaatar

Yekhe Khüriye was destroyed in the 1930s and later rebuilt as the modern-day capital city Ulaanbaatar (“Red Hero”). Among the surviving temples, the latest one still standing is Migjid Janraisig, or Temple (fig. 11), which was built with donations from the entire Khalkha population to commemorate Mongolia’s independence from the Qing in 1911. The Gandan Monastery continued to serve as the only practicing monastery and the only Buddhist educational center throughout the socialist period (1924–1992).

Migjid Janraisig, or Avalokiteshvara Temple, Gandan Monastery, Ulaanbaatar. Photograph by Tim Whitby/ Alamy Stock Photo

Yekhe Khüriye’s other constituents were merchants, who occupied two streets known as Eastern and Western Porters, east and west of Züün Khüriye. Chinese merchants were settled in Maimaicheng, or Traders’ Town to the southeast (fig. 12). Jügdür denotes all these commercial sections on the map in grayish blue color. The same color applies to the Russian settlement situated around the Russian Consulate (fig. 13), opened in Yekhe Khüriye in 1861, on Maakhuuz Tologai Hill to the east of Züün Khüriye, later renamed Consulate’s Hill. Jügdür depicts the hill, where the Russian Orthodox Holy Trinity Church was also built.

Jügdür (fl. late 19th–early 20th century); Detail of Maimaicheng, Map of Capital Yekhe Khüriye; Mongolia; 1912; colors on cotton, 19 5/8 × 37 7/8 in. (50 × 96 cm); Bogd Khan Palace Museum, Ulaanbaatar

Ivan Korostovets (Russian, 1862–1933); Russian Consulate and Holy Trinity Church; Yekhe Khüriye, Mongolia; 1912; photograph; photograph by Alamy Stock Photo / FLHC 81

Yekhe Khüriye was located in the valley of two rivers: in the painting, the Selbe River runs in the middle of Züün Khüriye, and the Tuul River runs south of the two circles. On the bank of the Tuul River, Jügdür depicts the Bogd Khan’s palaces: the largest is the Green Palace (also known as Winter Palace, Shirabpeljeiling, or Bilig Badaruulugchi süme), to the east, Norbuling süm and Khayistai Labrang; to the west, the Bogd’s White Palace (also known as Güngadejidling süme) and Pandelin or Narkhajid Temple. At the bottom of the painting, behind the hills, Jügdür depicts another dedicated to that was not part of Yekhe Khüriye (fig. 14).

Jügdür (fl. late 19th–early 20th century); Detail of Manjushri monastery, Map of Capital Yekhe Khüriye; Mongolia; 1912; colors on cotton; 19 5/8 × 37 7/8 in. (50 × 96 cm); Bogd Khan Palace Museum, Ulaanbaatar

While primarily a Buddhist monastery and a major pilgrimage site for the Mongols, Yekhe Khüriye served several other important functions. As the main seat of the Jibzundamba Khutugtus, Yekhe Khüriye was the political center of Mongolia, and its political importance strengthened with years. After the Bogd Khan’s death and with the establishment of the new socialist government in 1924, Yekhe Khüriye was destroyed and rebuilt, and remains to this day the capital city Ulaanbaatar.

Yekhe Khüriye was also an important trade center. Several foreign businesses of large or small scale, such as the American Trading Company, operated in Yekhe Khüriye, and the important visitors to Yekhe Khüriye included a then young engineer, later the thirty-first President of the United States, Herbert Hoover (1874–1964), the paleontologist Roy Chapman Andrews (1884–1960), the Swedish missionary Frans-August Larson (1870–1957), the Thirteenth (1876–1933), and the explorer Aleksei Pozdneev (1851–1920), among others.

Yekhe Khüriye was an important cultural center, where many excellent artworks were produced. The city regularly hosted both secular festivals and religious ceremonies. Given textual references to the Jibzundambas as rulers who fused political and religious spheres of power (, or Buddhist Government), these images, as well as Yekhe Khüriye itself—its structure, the activities it sponsored, roles it played, and celebrations it hosted—all were embodiments of the ruler’s dual rulership.

See Charles Bawden, The Jebtsundamba Khutukhtus of Urga (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1961); Aleksei M. Pozdneev, Mongolia and the Mongols, trans. John Roger Shaw and Dale Plank, Reprint, vol. 1 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1896) 1971, 1880.

See Dashdemberel Bat-Erdene and O. Mendsaikhan, eds., Masterpieces of Bogd Khan Palace Museum (Ulaanbaatar: Bogd Khan Palace Museum, 2011); Zara Fleming and J.Lkhagvademchig Shastri, eds., Mongolian Buddhist Art: Masterpieces from the Museums of Mongolia, Vol. 1, Thangkas, Appliqués and Embroideries, Part 2 (Chicago: Serindia, 2011).

See Gilles Béguin, “The Great Monuments of Lhasa as Presented in the Architectural Paintings of the Musée Guimet,” in Lhasa in the Seventeenth Century: The Capital of the Dalai Lamas, ed. Françoise Pommaret, Brill’s Tibetan Studies Library 3 (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 53–63; Knud Larsen and Amund Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas: Traditional Tibetan Architecture and Townscape (Boston: Shambhala, 2001).

The word aimag denotes two things: (1) a province in Mongolia; there are twenty-one aimags in modern-day Mongolia; and (2) Geluk monasteries in Mongolia organize their monks into units called aimags, which often follow a model of Tibetan regional houses khangtsen (khang tsan).

Uranchimeg Tsultemin, A Monastery on the Move: Art and Politics in Later Buddhist Mongolia (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2020), 134, based on D. Damdinsüren, Ikh Khüreenii Nert Urchuud [Eminent Artists of Ikh Khüree] (Ulaanbaatar: Mongolpress, 1993). On Mongolian paintings, see Nyam-Osoryn Tsultem, Mongol’skaja Nacional’naja Živopis “Mongol Zurag”/Development of the Mongolian National Style Painting “Mongol Zurag Brief, [In Russian, English, French, and Spanish] (Ulaanbaatar: Gosizdatel’stvo, 1986); Nyam-Osoryn Tsultem, Mongoliin Uran Zurgiin Khögjij Irsen Toim [Development of Mongolian Painting], ed. Narmandakh Tsultem (Ulaanbaatar: BCI Publishing, 2018).

The inscription added to the painting The Capital Yekhe Khüriye.

For additional historical context on the turbulent years in late and post-Qing period, see Matthew King, Ocean of Milk, Ocean of Blood: A Mongolian Monk in the Ruins of the Qing Empire (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019).

Lokesh Chandra, ed., Urga Kanjur, Śata-piṭaka series nos. 396-500 (Delhi: Sata-pitaka, 1980).. Chandra maintains Urga Kangyur was printed in 1913 to 1920.

Ngag dbang mkhas grub (Agwang Khayidub), “Khu Re Chen Mor Bzhengs Pa’i Byams Pa’i Sku Brnyan Gyi Dkar Chag Dad Pa’i Bzhin Ras Gsal Bar Byed Pa’i nor Bu’i Me Long,” in The Collected Works of Nag-Dban-Mkhas-Grub, Kyai-Rdor Mkhan-Po of Urga: Reproduced under the Instructions of the Ven. Gliṅ Rin-Po-Che from a Set of MSS. and Xylographic Prints from the Urga Blocks, ed. Nag-dban-mkhas-grub, vol.1 (Ladakh: S. W. Tashigangpa, 1972-1974), fols. 577-611. TBRC W16912–0588, vol. 3 fols. 367-472

For the later writers, see L. Dügersüren, Ulaanbaatar Khotiin Tüükhees [From the History of Ulaanbaatar] (Ulaanbaatar: Ulsyn Khevleliin Gazar, 1956); S. Pürevjav, Khuvsgaliin ömnöh Ikh Khüree [Prerevolutionary Ikh Khüree] (Ulaanbaatar: Ulsin Khevlelin Khereg Erkhlekh Khoroo, 1961).

Ngag dbang ye shes thub bstan rab ’byams pa (Agwang Ishitübden Rabjamba), “Skyabs Mgon Rje Btsun Dam Pa Rin Po Che’i Skye Khreng Rim Byon Rnams Dyi Rnam Thar Mdo Tsam Bgod Pa Pad Dgar ‘phreng Mjes Zhes Bya Ba Bzhugs So,” in The Life and Works of Jibcundampa I, ed. Lokesh Chandra, [In Tibetan and Mongolian] (New Delhi: Śata-Piṭaka Series, Jayed Press, 1982), fols. 10–11; Bstan pa bstan ’dzin, “Rje btsun dam pa’i sgu phreng,” in Chos sde chen po dpal ldan ’bras spungs bkra shis sgo mang grwa tshang gi chos ’byung dung g.yas su ’khyil ba’i sgra dbyangs, vol. 2 (Buddhist Digital Resource Center (BDRC), 2003), http://purl.bdrc.io/resource/W28810, fols. 416–18.

O. Sereeter, Mongoliin Ikh Khüree, Gandan Khiidiin Tüükhen Butetsiin Tovch [Survey of Historical Structure of Ikh Khüree and Gandan Monastery of Mongolia] (Ulaanbaatar: Mongol Ulsyn Undesnii Tov Arkhiv, 1999), 72.

Krisztina Teleki, Monasteries and Temples of Bogdiin Khüree (1651–1938) (Ulaanbaatar: Institute of History, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, 2011), 190.

See also Krisztina Teleki, Monasteries and Temples of Bogdiin Khüree (1651–1938) (Ulaanbaatar: Institute of History, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, 2011), 162–70.

For more about this monastery and others, see the digital database Documentation of Mongolian Monasteries, in Mongolian and English, https://www.mongoliantemples.org/en/.

Many of these visitors wrote articles or books about Yekhe Khüriye and Mongolia. See, for instance, Frans-August Larson, Larson, Duke of Mongolia (Boston: Little Brown & Co, 1930); Ivan Korostovets, Von Cinggis Khan zur Sowjetrepublik: Eine kurze Geschichte der Mongolei unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der neuesten Zeit (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1926); Roy Chapman Andrews, Across Mongolian Plains: A Naturalist’s Account of China’s “Great Northwest" (New York: Blue Ribbon Books, 1921)..

Uranchimeg Tsultemin, A Monastery on the Move: Art and Politics in Later Buddhist Mongolia (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2020), 176–211.

Teleki, Krisztina. 2011. Monasteries and Temples of Bogdiin Khüree (1651–1938). Ulaanbaatar: Institute of History, Mongolian Academy of Sciences.

Teleki, Krisztina. 2015. Introduction to the Study of Urga’s Heritage. Ulaanbaatar: Mongolian Academy of Sciences.

Tsultemin, Uranchimeg. 2020. A Monastery on the Move: Art and Politics in Later Buddhist Mongolia, esp. 143–211. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Uranchimeg Tsultemin, “Mongolian Map of Capital Yekhe Khüriye: Mapping Yekhe Khüriye’s Cityscape as the ‘Capital City,’” Project Himalayan Art, Rubin Museum of Art, 2023, http://rubinmuseum.org/projecthimalayanart/essays/mongolian-map-of-capital-yekhe-khuriye.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Cum nihil placeat pariatur deserunt eius ullam incidunt maxime sunt ipsam. Ipsa, provident, laudantium, rem assumenda laboriosam veniam autem voluptas sint officia distinctio enim aut explicabo fuga animi voluptatum earum recusandae excepturi atque dignissimos iste? Exercitationem, praesentium eum. Harum ut maiores expedita exercitationem perspiciatis soluta aperiam dolores natus unde, sequi vitae debitis ex aliquam quas eum reprehenderit esse. Cumque amet et earum necessitatibus, repellendus ullam ducimus corporis architecto culpa placeat eum odit cum iure illo vitae rerum! Ullam et suscipit culpa? Eos voluptatum laudantium iste vero impedit adipisci maxime magni natus voluptatibus.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.