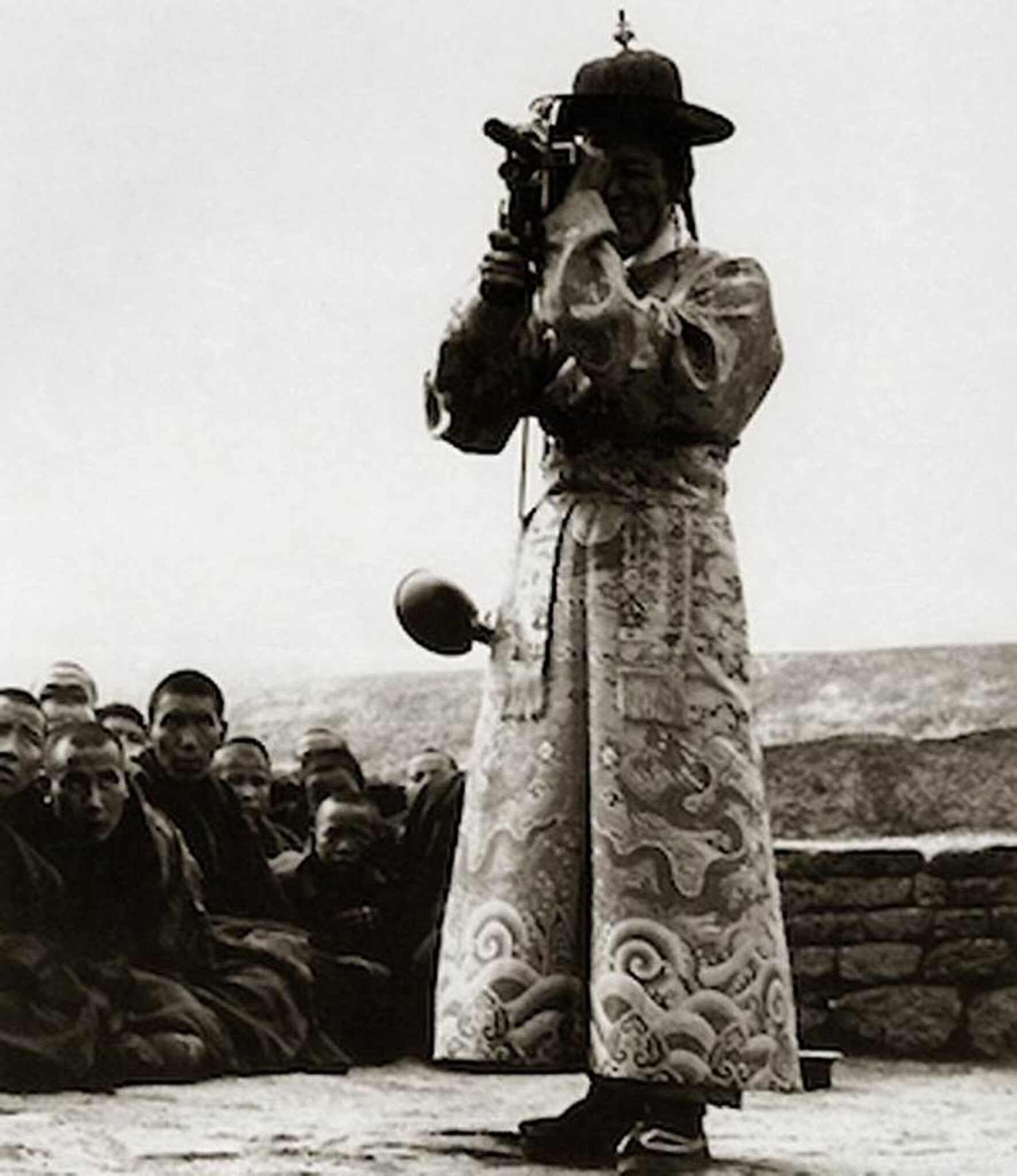

The British Empire was the largest empire in world history, ruling almost a quarter of the world’s land area and population at its height in the mid-twentieth century. The British achieved hegemony in India after the Battle of Plassey in 1757, and soon came to rule large areas of the Himalayas, including Kashmir and Ladakh. Several small Himalayan kingdoms, including Nepal, Bhutan, and Sikkim, were allowed to maintain semi-independence as buffer-states against Qing-controlled Tibet. The British briefly invaded Tibet in 1903–1904. After the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1912, the British became a major cultural and military influence on the Ganden Podrang government in Lhasa. India achieved independence in 1947, ending British rule in the Himalayas.

The Cultural Revolution was a political and social movement in communist China from 1966 to 1976. During this time, traditional culture across all of China came under violent attack, and almost all religious institutions were shut down and many were physically destroyed. In minority areas, ethnic differences and indigenous cultural practices, such as use of Tibetan language or dress, were seen as backward and subject to persecution, adding an additional racial dimension. Hundreds of thousands of Tibetans fled to India or Nepal, and many Himalayan artworks were destroyed or scattered abroad.

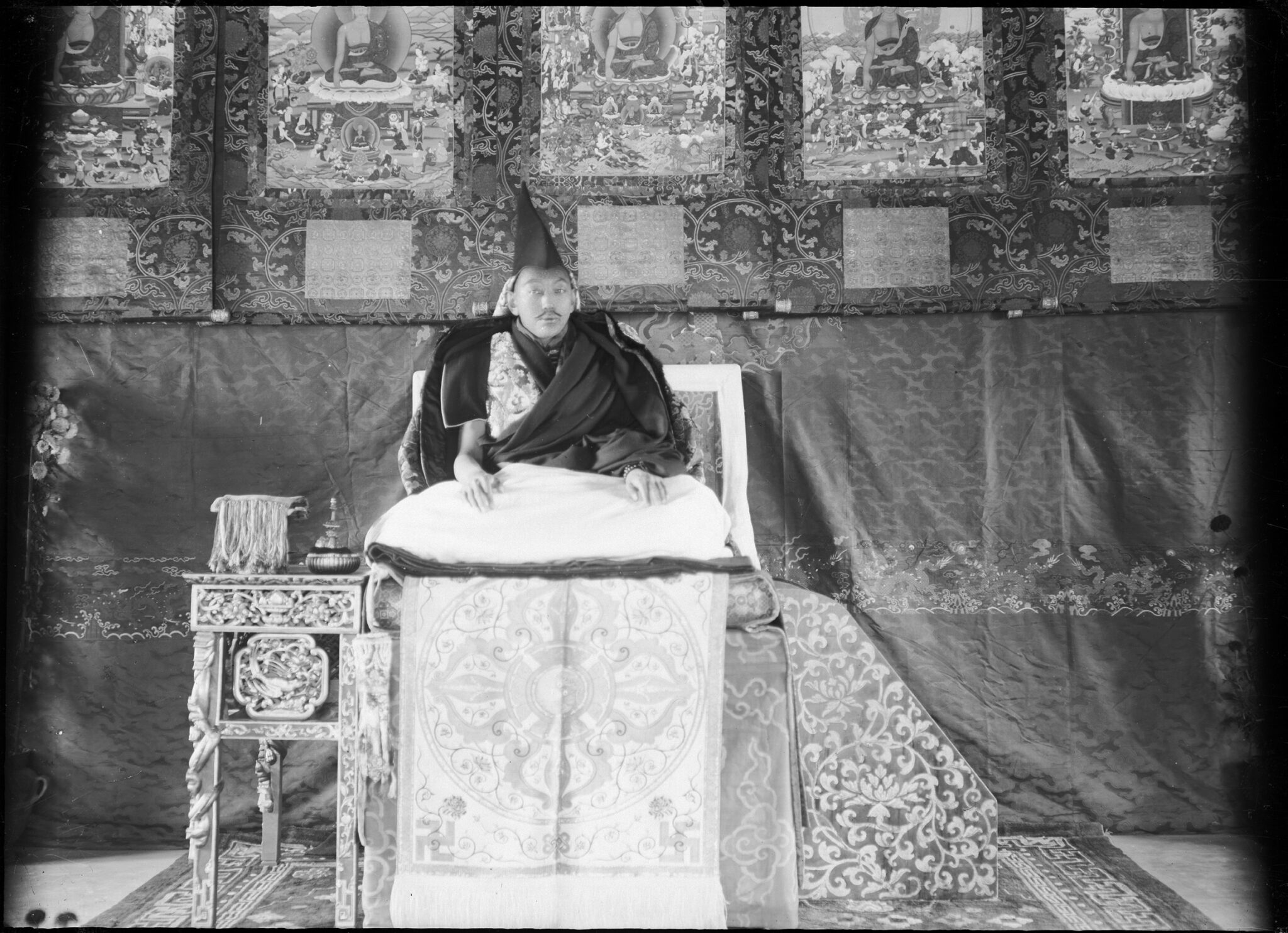

The Dalai Lamas are a tulku lineage that has played a central role in Tibetan history for the last five hundred years. In 1577 a Mongol khan gave the Geluk monk Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588) the title “Dalai Lama,” combining the Mongolian word for ocean, dalai (a reference to the depth of his knowledge), and the Tibetan word for guru, lama. Later, two previous incarnations were retroactively identified. The fifth incarnation, Ngawang Gyatso (1617–1682), allied with another Mongol khan to unite most of the Tibetan Plateau, forming the Ganden Podrang government that would govern Tibet until 1959. Since the Communist takeover, the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama has lived in exile at Dharamshala in India. The Dalai Lamas are understood to be emanations of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

Hindus and Buddhist believe that all beings die and are reborn in new bodies, or “incarnations.” While reincarnation is recognized across the Buddhist world, in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, some important teachers (lamas) are thought to be able to control this process. Their successive incarnations, known as tulkus (emanation bodies), formed incarnation lineages such as Dalai Lamas, Panchen Lamas, Karmapas, and others.

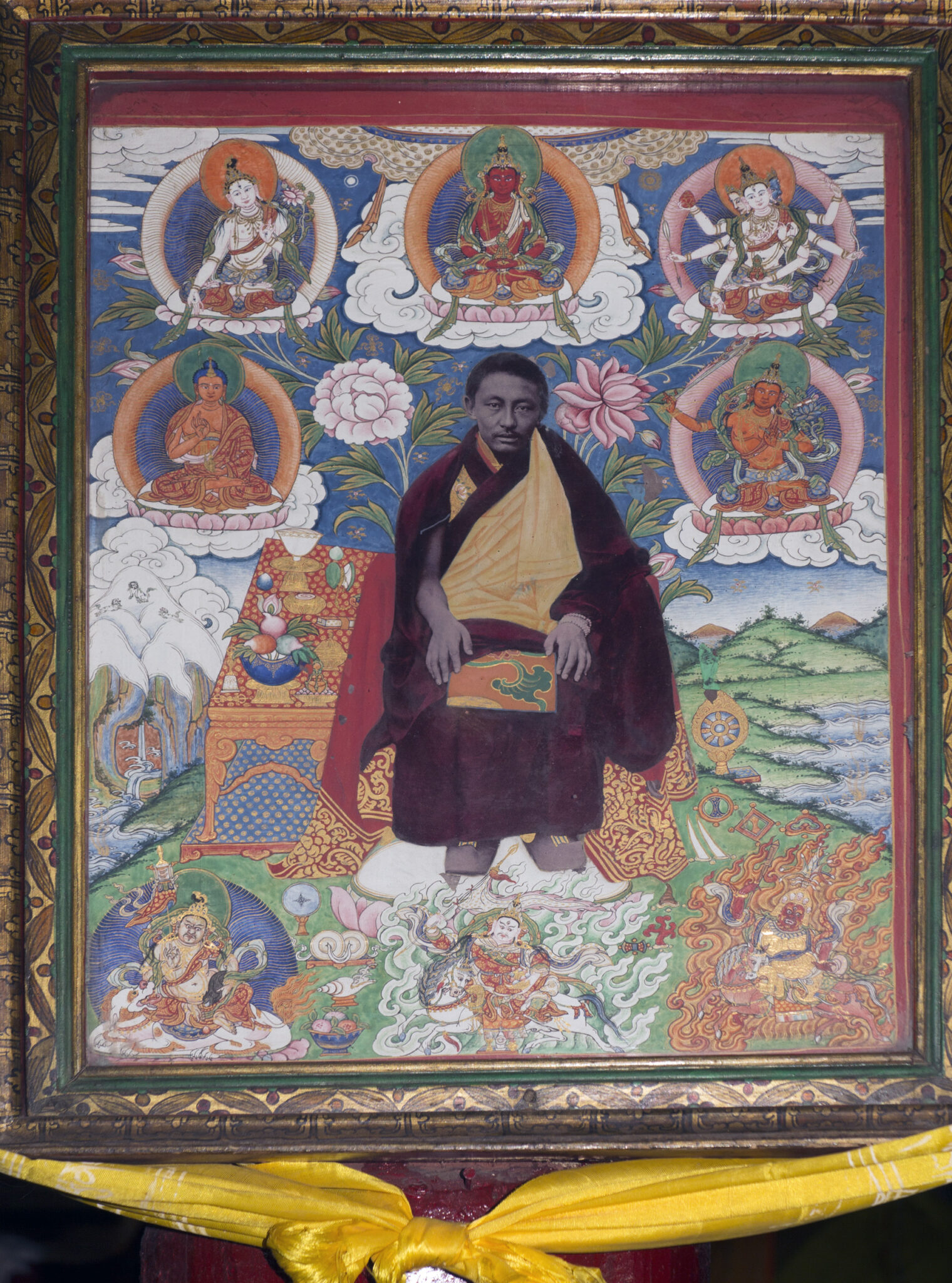

Socialist realism was an artistic movement practiced during the twentieth century in communist countries, especially China and the Soviet Union. Socialist realism idealistically portrays the lives of working people, often as propaganda to inspire the masses for the state’s economic and social campaigns. Most socialist realism derived from the European tradition of oil painting, but some images used traditional Asian visual forms and conventions, including Tibetan thangka painting and Chinese woodblock prints.