Bon is an indigenous religion of Tibet. Originally, Bon were a group of non-Buddhist ritual specialists in the court of the Tibetan emperors. From the eleventh century onward, an organized religion called Yungdrung Bon, or “Eternal Bon,” took shape. Yungdrung Bon developed in dialogue with Buddhism, incorporating deities called buddhas, scriptures modeled on the Buddhist canon, monks, and the establishment of monasteries. Followers of Yungdrung Bon trace their own origins to a founder called Tonpa Shenrab, who arrived from the semi-mythical land of Zhangzhung in western Tibet. The word “Bon” can also refer to the many non-organized indigenous religious practices, including the worship of mountain deities and making namkha. A follower of Bon is called a Bonpo.

In the Himalayan context, iconography refers to the forms found in religious images, especially the attributes of deities: body color, number of arms and legs, hand gestures, poses, implements, and retinue. Often these attributes are specified in ritual texts (sadhanas), which artists are expected to follow faithfully.

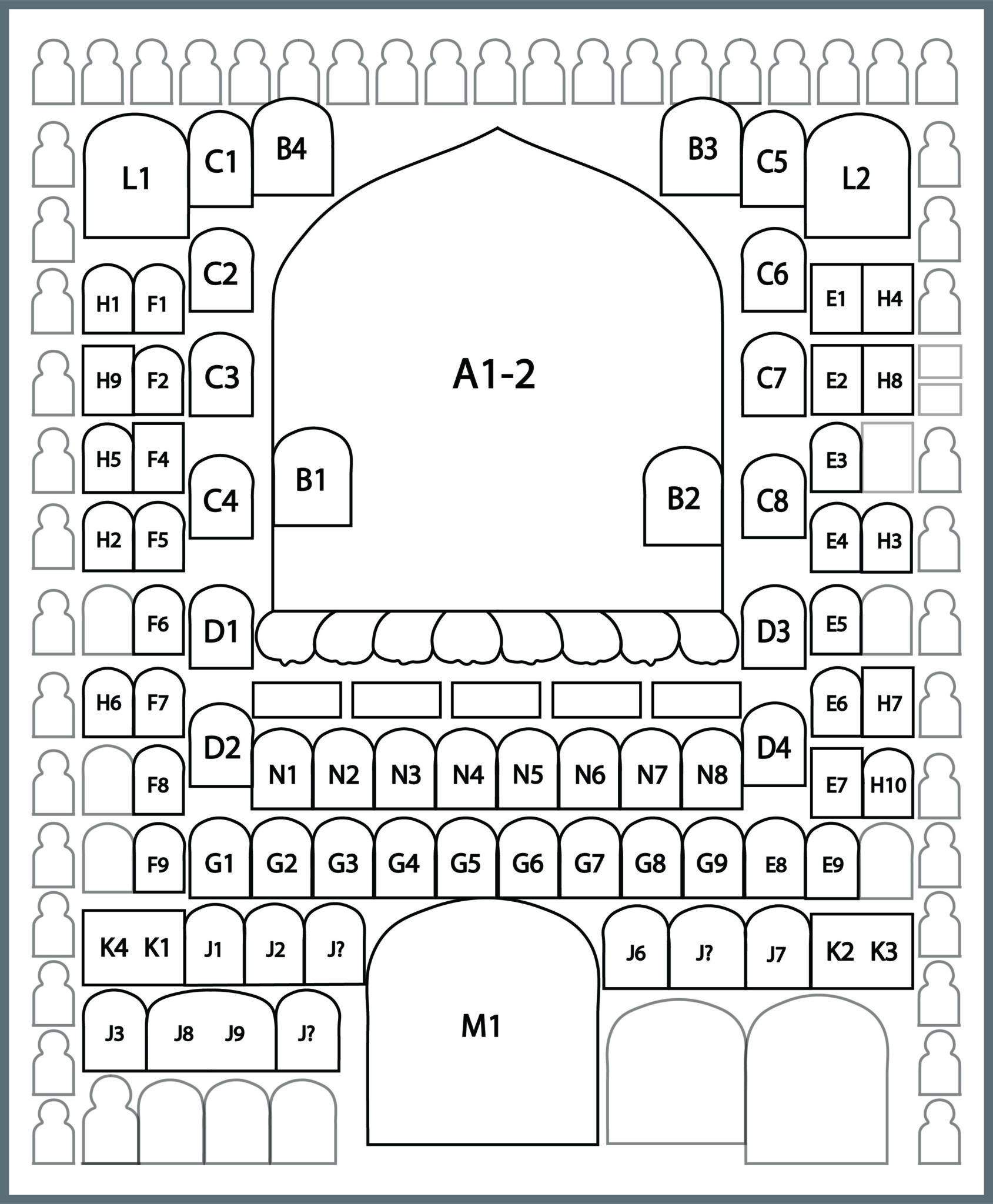

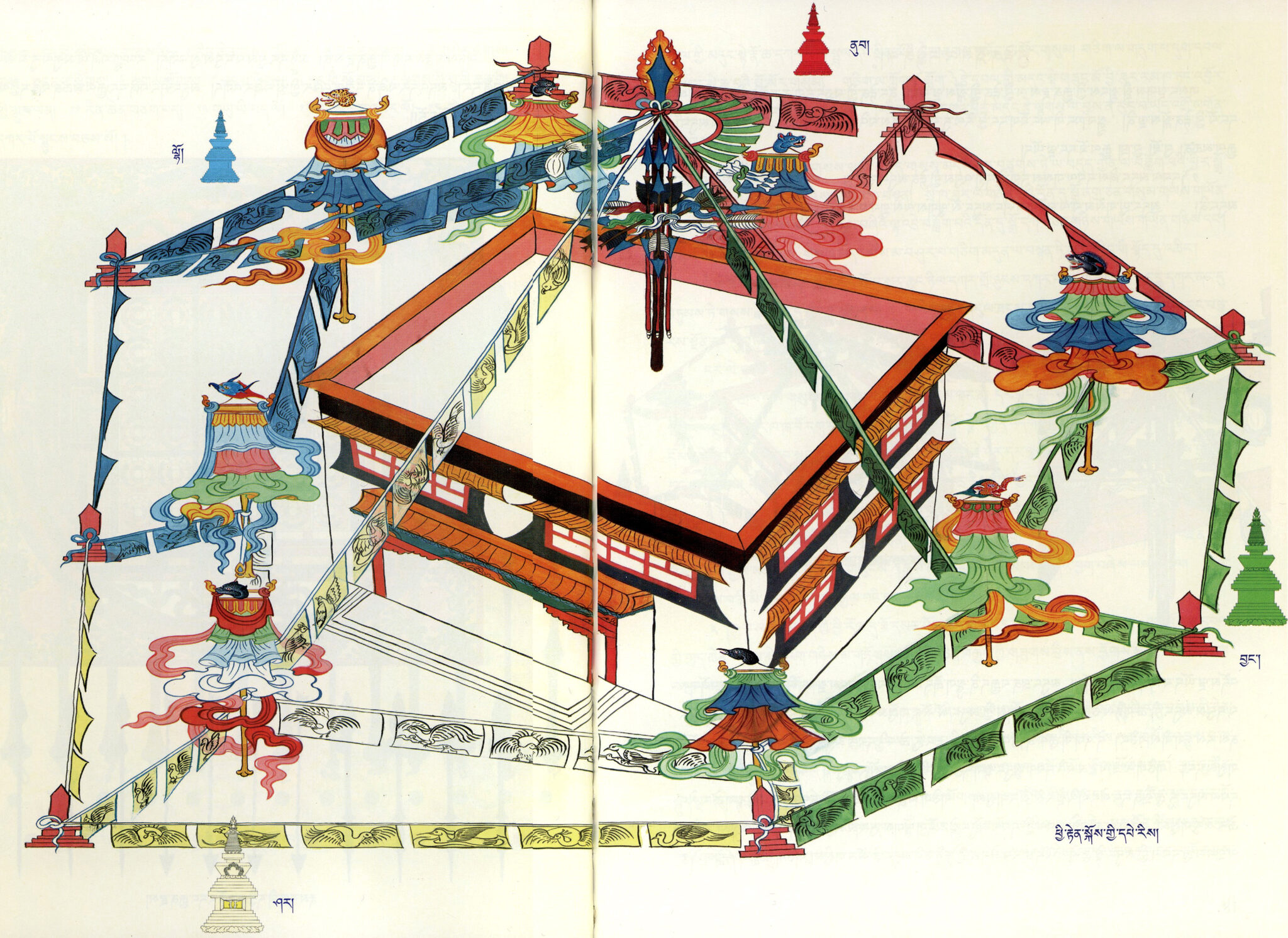

In Vajrayana Buddhism or Bon, a mandala refers to a cosmic abode of a deity, usually depicted as a diagram of a circle with an inscribed square that represents the deity enthroned in their palace, surrounded by members of their retinue. Mandalas can be painted, three-dimensional models, architectural structures, such as temples or stupas, or composed as arrangements of images within a temple. The instructions for creating and visualizing mandalas are usually found in ritual texts, such as tantras and sadhanas. Mandalas can be used in initiation ceremonies, visualized by a practitioner as part of deity yoga, consecrated and used to represent the divine presence within ritual space, offered to the deities as representations of the entire universe. A similar concept in Hinduism is a yantra.

The swastika is an ancient Eurasian symbol, found in rock carvings since prehistoric times. In Hinduism, Buddhism, and Bon, the swastika is a common and auspicious decorative design, symbolizing the motions of the sun, the wheel of reincarnation, and the eternal nature of the teachings. In Tibetan, it is yungdrung (“Eternal”), the principal religious symbol of the Bon religion, and the organized system of Bon that emerged in dialogue with Buddhism is generally referred to as Yungdrung Bon. The strongly negative association of this design in Western countries is due to its appropriation by the twentieth-century Nazis as a symbol of their racial theories.

Tantra was a religious movement in India around the fifth to seventh centuries, and its practices are part of Buddhism and Hinduism. The word tantra also refers to texts which transmit tantric practices. In Buddhism, tantra is also called Vajrayana, “The Vajra Vehicle.” Tantric ritual and art are characterized by deity yoga, mandalas, mantras, abhisheka (initiation), wrathful deities, and ritual sexual union. In Hinduism, tantrism was often associated with the worship of Shiva and various goddesses (shakti). A practitioner of tantra is called a “tantrika.” Tantra is also a genre of texts that have been variously categorized. Most common is the division of tantras into four categories: Kriya Tantra, Charya Tantra, Yoga Tantra, and Highest Yoga Tantra.

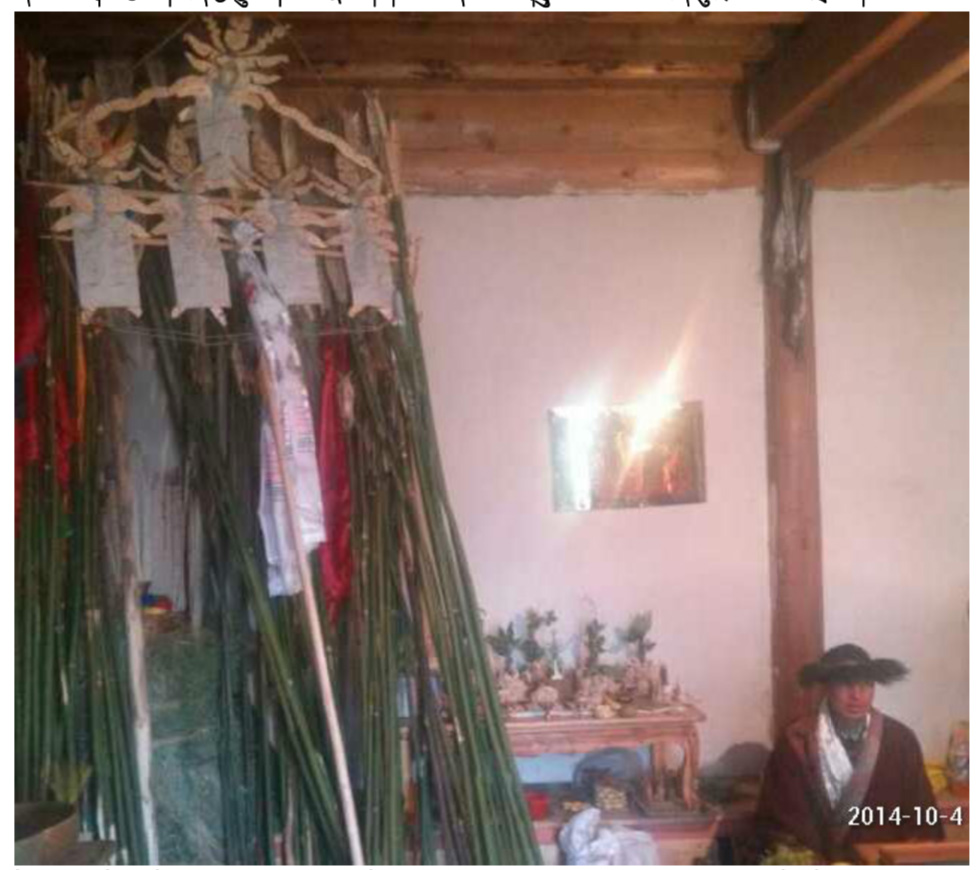

In Tibetan Buddhism and Bon, a torma is a sculpture made from butter and barley dough that is usually dyed. Tormas are used for a variety of purposes in rituals, and can be offerings to the gods, or consecrated as receptacles of divine power. In exorcistic rituals, evil forces are invited into the tormas, which are then brought outside of the settlement and destroyed. These tormas can be understood as ransom in exchange for victims plagued by spirits, or as a substitute for animal sacrifice. Some monasteries have traditions of making huge, beautifully decorated tormas, which are viewed by pilgrims at festivals like the Monlam Chenmo. Tormas can be figurative (images that depict the gods or other scenes), or they can be aniconic (symbolic shapes).