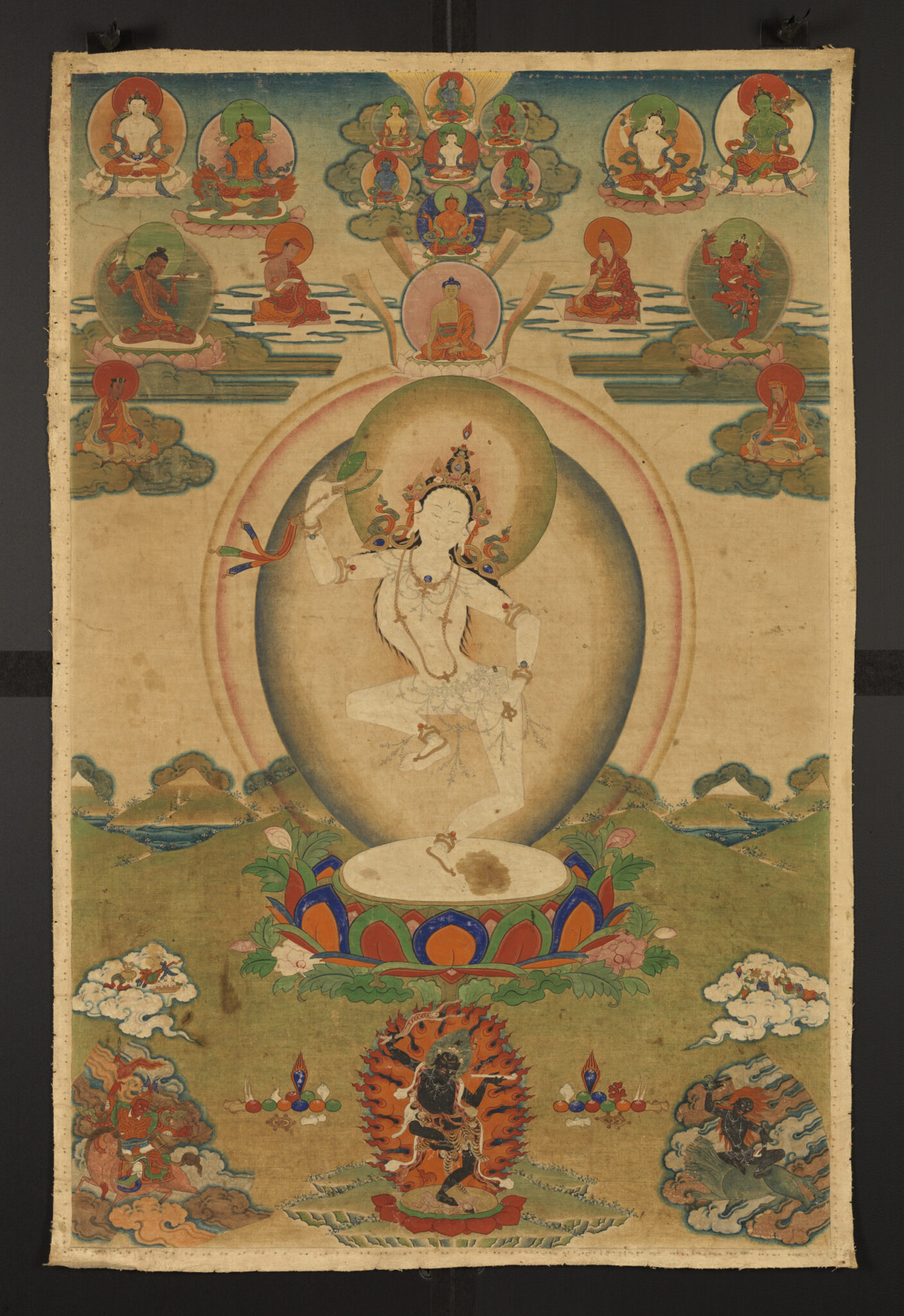

In India and Tibet, a charnel ground is a place where dead bodies are brought for cremation or exposure to be consumed by vultures. In early Buddhism, practitioners would come to these places to meditate on death and impermanence. In tantric forms of Hinduism and in Vajrayana Buddhism, these charnel grounds became an important gathering place for yogins, and a source of transgressive imagery for iconographies of tantric deities and the siddhas who embody these practices.

Chod is a ritual technique in the Nyingma and Kagyu traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, as well as in Bon. In a Chod ritual, the practitioner visualizes dismembering of his or her body and offering it to demons. This method is “cutting through” or destroying the ego, which is the primary impediment to awakening (enlightenment).

Emptiness is a core concept of the Madhyamaka philosophical tradition of Mahayana Buddhism, most famously formulated by the Indian philosopher Nagarjuna (ca. second to third century CE) and elaborated by Chandrakirti (c. seventh century CE). Emptiness (Skt. shunyata) refers to the absence of inherent existence, meaning that although all things, including the self, exist insofar as we perceive them, they are constantly changing and dependent on causes and conditions, and thus empty of inherent existence. Buddhas are said to perceive both of these relative and absolute truths at once. Other Buddhist traditions, for instance Dzogchen and the Jonang, interpret emptiness as a primordial state of radiant awareness underlying the phenomenal world.

Impermanence is a core concept in Buddhism. The Buddha taught that all beings, things, and thoughts are constantly appearing, changing, and passing away in samsara. We suffer because we are attached to these unstable things. In Madhyamaka philosophy, impermanence is a central part of the doctrine of emptiness.

Visualization is a process of using one’s imagination to transform reality. A practitioner imagines in their mind’s eye the deity with the associated enlightened qualities they wish to embody themselves. When focused on a specific deity, visualization and related ritual practices are called deity yoga. Visualization is a fundamental element of such practices described in texts known tantras, which define a system of meditation and ritual meant to transform the mind and body.