In Buddhism, dharma refers to the teachings of the Buddha, and to the Buddhist religion itself. In Hinduism, dharma means law, custom, morality, or a way of doing things. The word has other contextual meanings in different Indian religious traditions.

The Kagyu are a major Later Diffusion tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. The Kagyu trace their lineages back to the Mahasiddhas, the great tantric masters of medieval India. The Kagyu are known for their yogic practices, as well as the teaching of Mahamudra, or the “Great Seal.” The Kagyu tradition includes many different branches, such as the Karma, Drukpa, Drigung, Tselpa, Pakmodru, and others. The most influential leaders of the Karma Kagyu are the Karmapas, a tulku lineage associated with that Kagyu branch. In Bhutan, the Drukpa Kagyu tradition serves as the state religion. A follower of the Kagyu is called a Kagyupa.

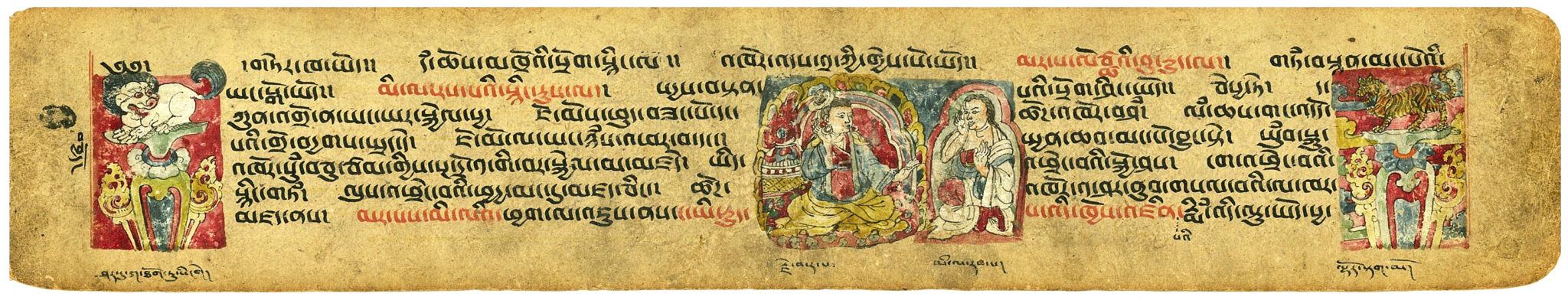

In Buddhism, merit is accumulated positive karma, or positive actions, that lead to positive results, such as better rebirths. Buddhists gain merit by reciting mantras, donating to monasteries and those in need, performing pilgrimages, commissioning artworks, reproducing and reciting Buddhist texts, and other deeds with good intentions. It is believed that merit can also be transferred to others through rituals performed to gain merit for deceased family members help them achieve a better rebirth. Merit making is an important motivation for positive ritual action, and is a prerequisite for success of religious and even secular activity.

A practice of hiring and commissioning artists to create works of art. In religious context patrons were often rulers, religious leaders, as well as ordinary people. (see also donor)

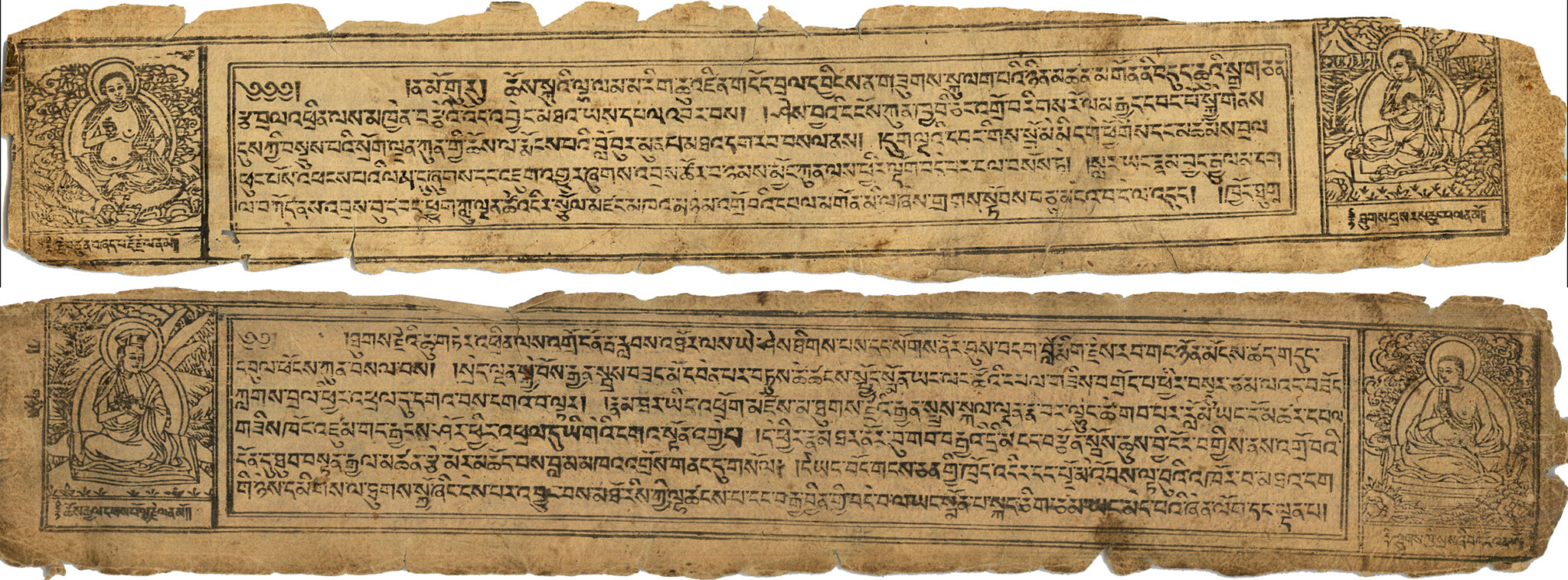

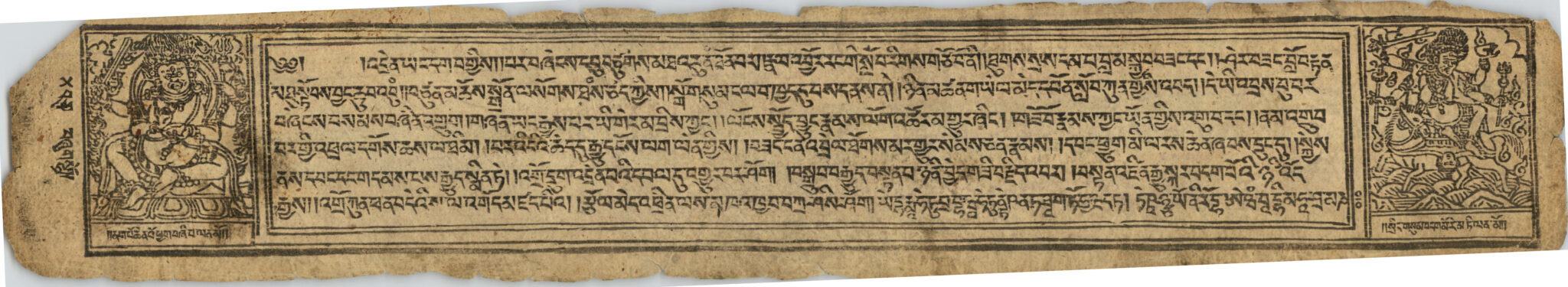

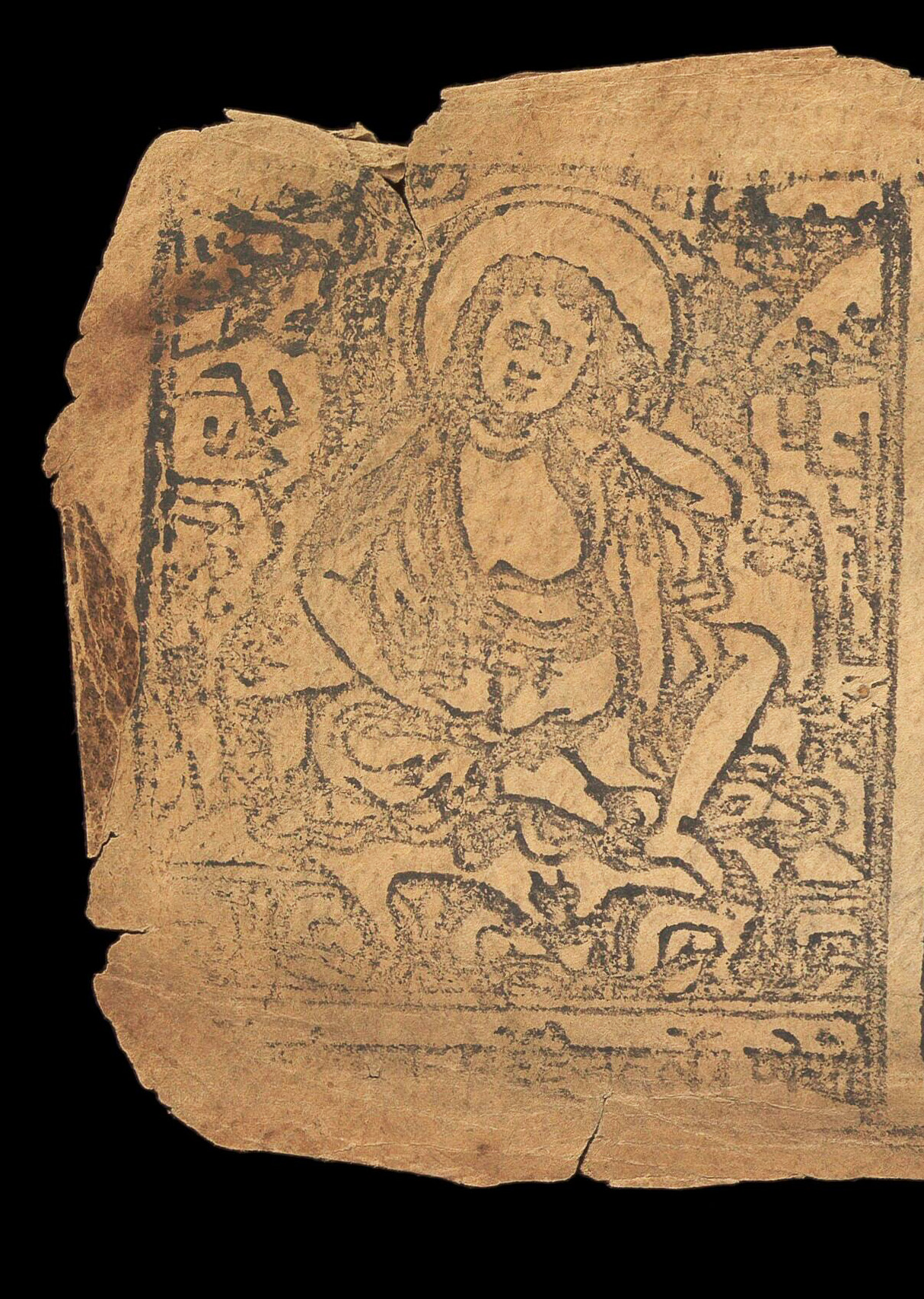

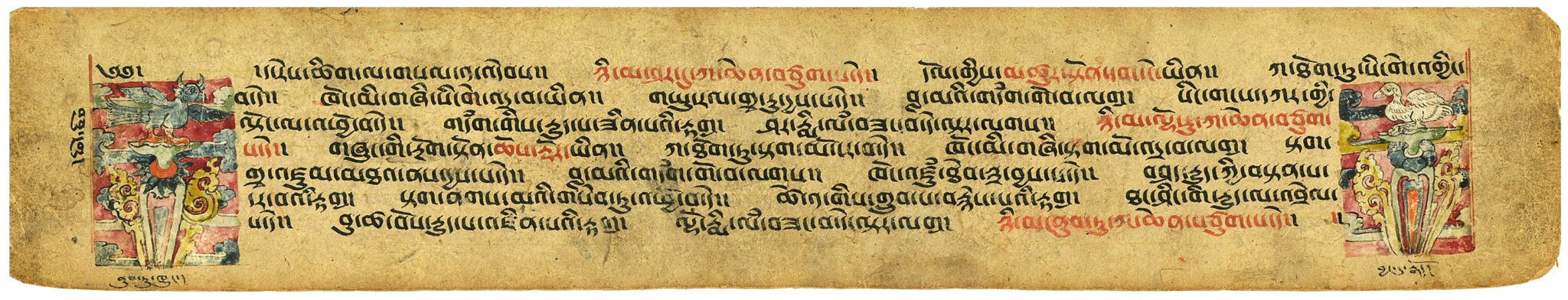

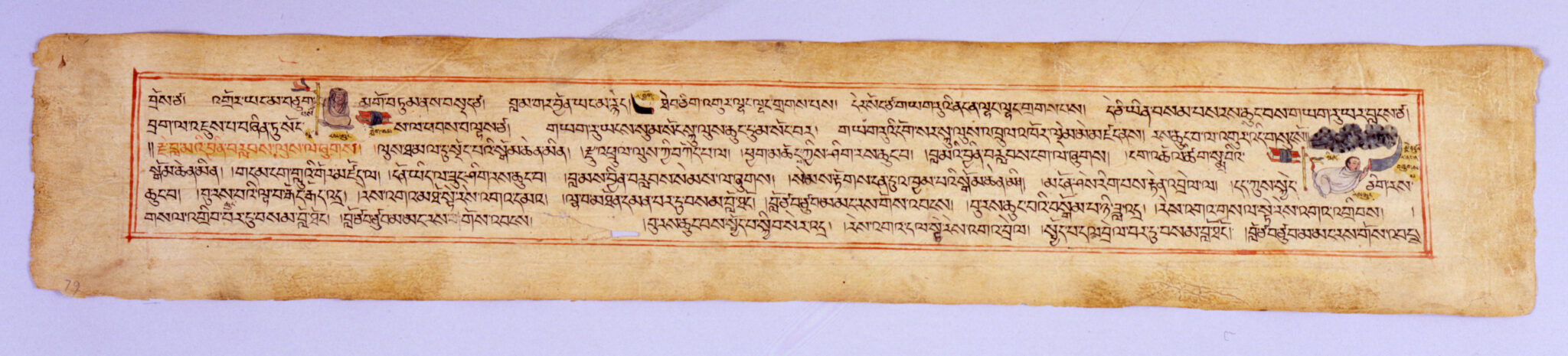

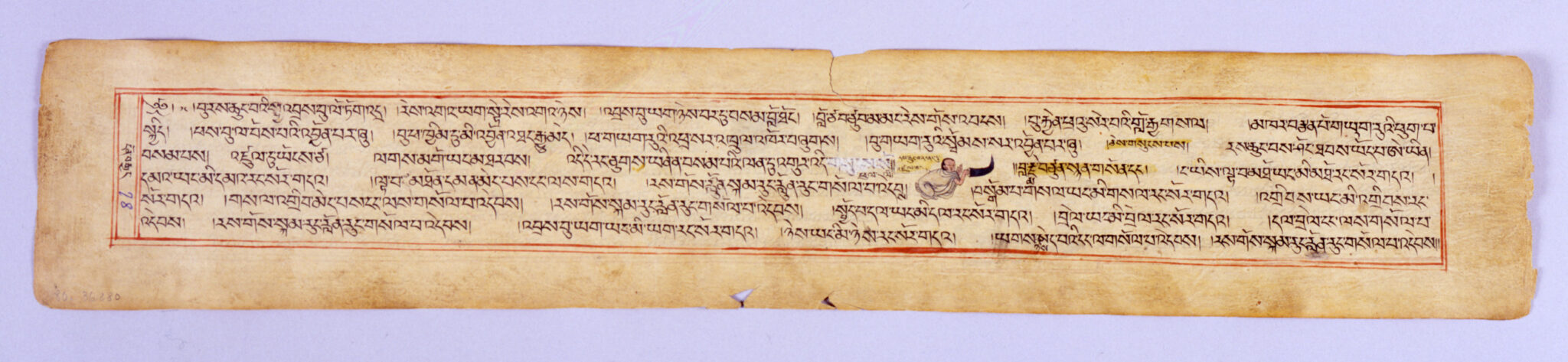

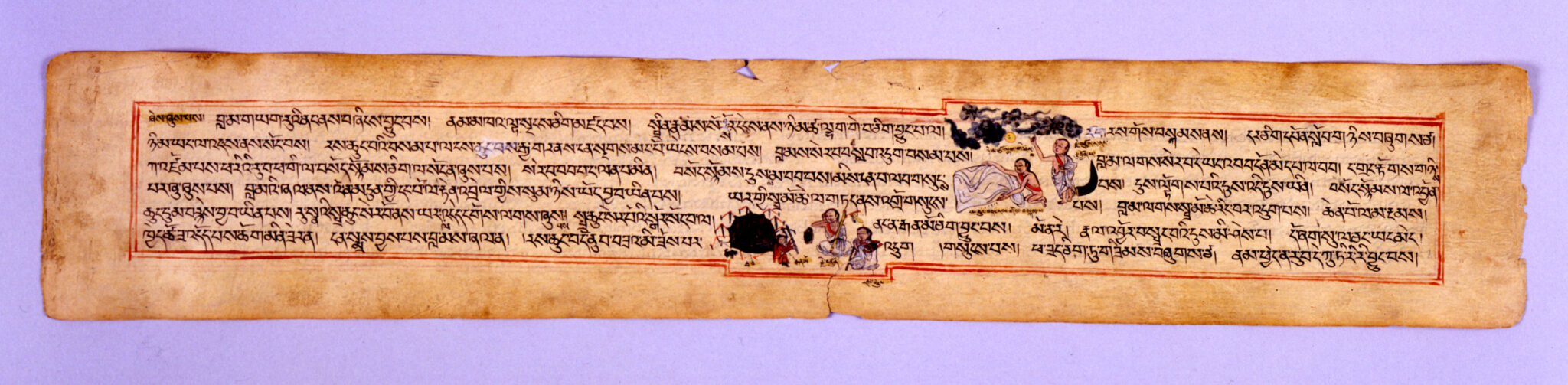

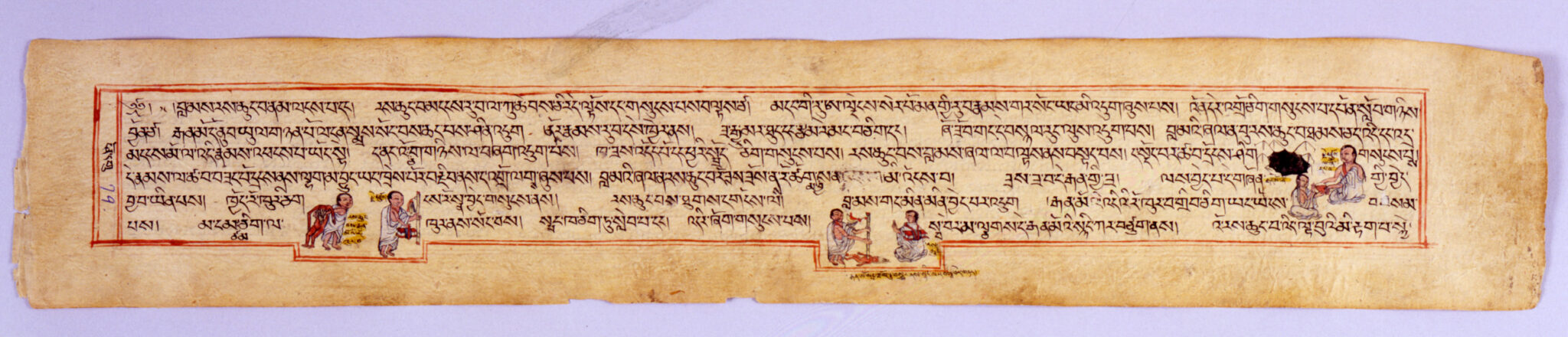

A pecha is a traditional form of Tibetan book, a format developed from Indian palm leaf manuscripts (pothis). Pechas usually have long, narrow, horizontal pages. The pages are not bound, but instead are placed between wood covers and then wrapped tightly with cloth. When pechas are read, they are placed on a flat surface and the unbound pages are flipped over away from the viewer. Pechas can be manuscripts or printed.

Historically, Tibetan Buddhism refers to those Buddhist traditions that use Tibetan as a ritual language. It is practiced in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, Ladakh, and among certain groups in Nepal, China, and Russia and has an international following. Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in two waves, first when rulers of the Tibetan Empire (seventh to ninth centuries CE), embraced the Buddhist faith as their state religion, and during the second diffusion (late tenth through thirteenth centuries), when monks and translators brought in Buddhist culture from India, Nepal, and Central Asia. As a result, the entire Buddhist canon was translated into Tibetan, and monasteries grew to become centers of intellectual, cultural, and political power. From the end of the twelfth century, Tibetans were exporting their own Buddhist traditions abroad. Tibetan Buddhism integrates Mahayana teachings with the esoteric practices of Vajrayana, and includes those developed in Tibet, such as Dzogchen, as well as indigenous Tibetan religious practices focused on local gods. Historically major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism are Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Geluk.