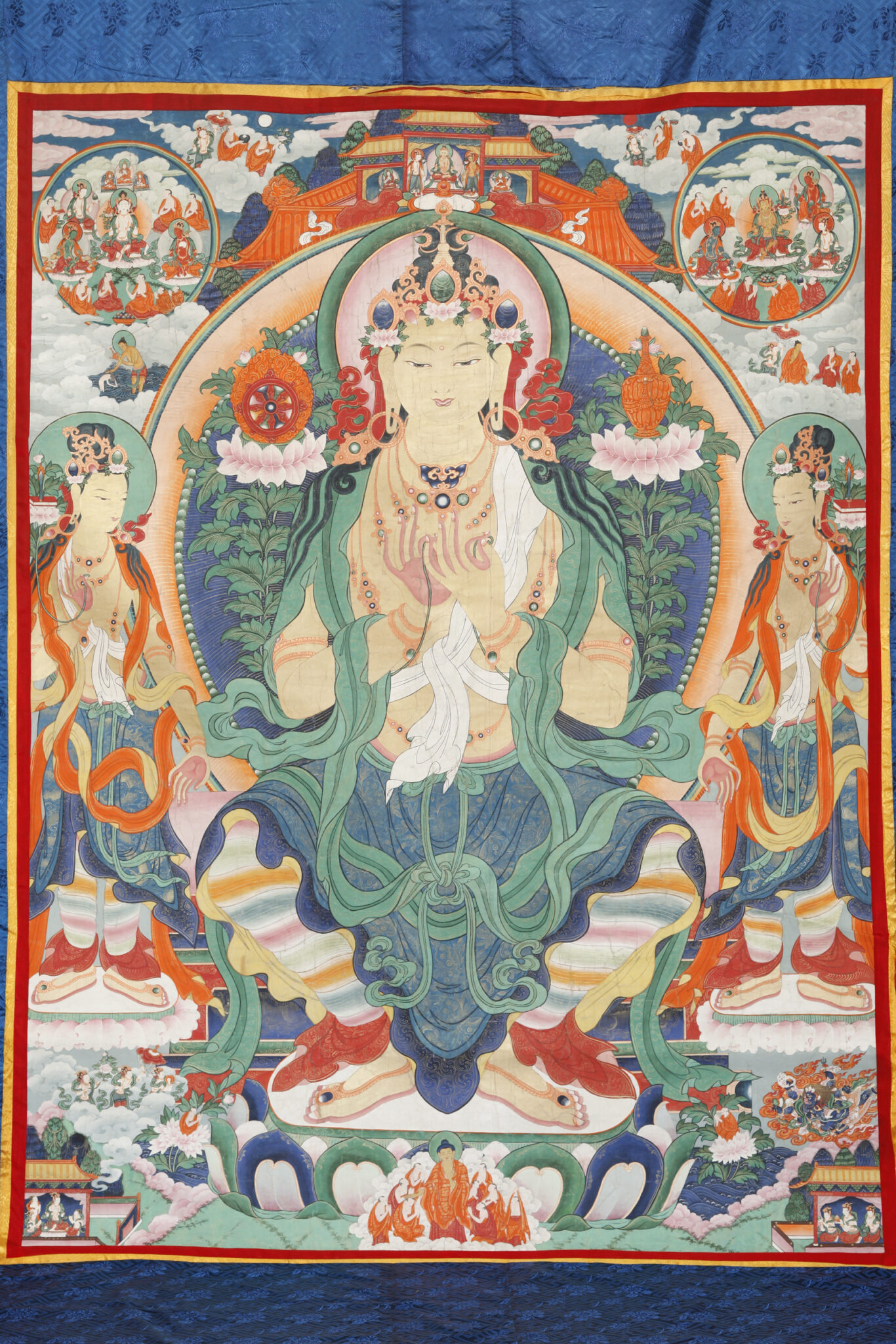

The Dalai Lamas are a tulku lineage that has played a central role in Tibetan history for the last five hundred years. In 1577 a Mongol khan gave the Geluk monk Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588) the title “Dalai Lama,” combining the Mongolian word for ocean, dalai (a reference to the depth of his knowledge), and the Tibetan word for guru, lama. Later, two previous incarnations were retroactively identified. The fifth incarnation, Ngawang Gyatso (1617–1682), allied with another Mongol khan to unite most of the Tibetan Plateau, forming the Ganden Podrang government that would govern Tibet until 1959. Since the Communist takeover, the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama has lived in exile at Dharamshala in India. The Dalai Lamas are understood to be emanations of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

Hindus and Buddhist believe that all beings die and are reborn in new bodies, or “incarnations.” While reincarnation is recognized across the Buddhist world, in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, some important teachers (lamas) are thought to be able to control this process. Their successive incarnations, known as tulkus (emanation bodies), formed incarnation lineages such as Dalai Lamas, Panchen Lamas, Karmapas, and others.

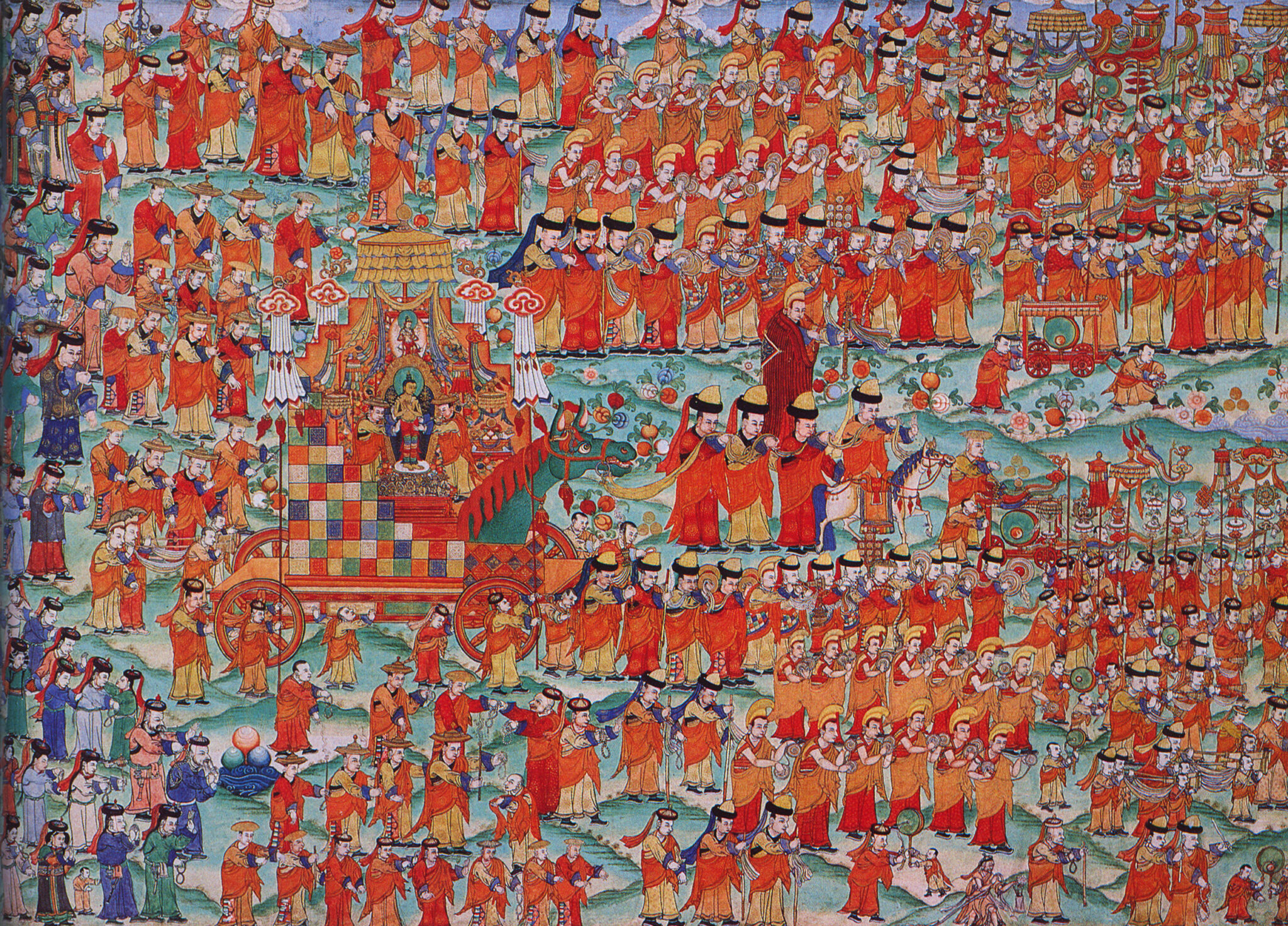

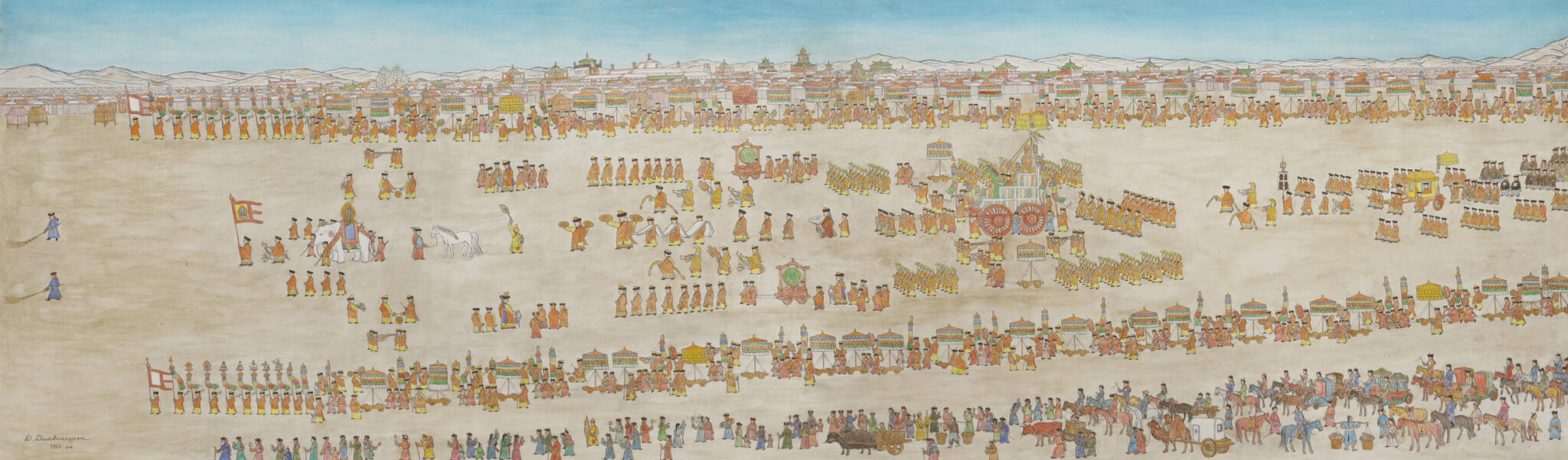

The Jibzundambas (from the Tibetan Jetsun dampa “venerable/reverend noble one”) were the most important lineage of tulkus in Khalkha Mongolia from 1639 to 1924, considered below only the Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas in prestige within the Geluk tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. While the Jibzundamba lineage traces its previous incarnations back to the Tibetan polymath and traveler Taranatha (1575–1634), the first formally enthroned Jibzundampa was the Mongolian prince and artist Zanabazar (1635–1723). As the Jibzundampa’s authority grew, their mobile monastery, called “the great encampment” (Mgl: yekhe khüriye), would gradually settle and develop into Mongolia’s modern capital, Ulaanbaatar. The eighth Jibzundamba ruled as khan of Mongolia from 1911 to 1924.

The Khalkha are one of the major historical subgroupings of the Mongols. Historically ruled by leaders descended from Chinggis Khan, the Khalkha inhabited a territory roughly the same as the country called Mongolia today. Other important Mongol groups after the fall of the Mongol Empire include the Chahars, who lived in what is today the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in China, the Oirat or Dzungars, who lived in Central Asia, and the Khoshut, who lived in the northern Tibetan Plateau.

The Newars are traditional inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal. The Newars speak a Tibeto-Burman language (Newari) and practice both Hinduism and Buddhism. The Newars are inheritors of one of the oldest and most sophisticated urban civilizations of the Himalayas, and Newar arts and artisans have been celebrated all across the Himalayan world since the Licchavi period.

The Panchen Lamas are an important tulku, or reincarnated lama lineage, in Tibet considered second in prestige within the Geluk tradition only to the Dalai Lamas. The Fifth Dalai Lama (1617–1682) declared that his tutor Lobzang Chokyi Gyeltsen (1570–1662) was the incarnation of Amitabha and granted him the title Panchen. Three “pre-incarnations” were identified, making Lobzang Chokyi Gyeltsen formally the fourth in the lineage. A special teacher-student relationship exists between the Dalai and Panchen lamas, when one passes away the other takes charge of identifying and educating the new incarnation. The traditional seat of the Panchen Lamas is Tashilhunpo Monastery in Shigatse.