Buddha Shakyamuni, or simply “The Buddha,” is an epithet for Siddhartha Gautama, the founder of the Buddhist religion. While the exact dates of Siddhartha’s life are debated, scholars generally place him in the sixth to fifth century BCE. According to early Buddhist narratives, Siddhartha was born a prince of the Shakya clan in what is now northern India and southern Nepal. Choosing to leave his palace and family for a life as a religious ascetic, Siddhartha achieved enlightenment while meditating under the Bodhi Tree. Siddhartha spent the rest of his life as a wandering teacher, gathering disciples to form the early Buddhist monastic community (sangha). Buddha Shakyamuni is revered all over the Buddhist world today.

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a being who has made a vow to become a buddha or awakened. In the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, many bodhisattvas are understood as deities with enormous powers who delay their final enlightenment, remaining in the phenomenal world to help suffering beings. Among such great bodhisattvas are Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Maitreya.

Hindus and Buddhist believe that all beings die and are reborn in new bodies, or “incarnations.” While reincarnation is recognized across the Buddhist world, in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, some important teachers (lamas) are thought to be able to control this process. Their successive incarnations, known as tulkus (emanation bodies), formed incarnation lineages such as Dalai Lamas, Panchen Lamas, Karmapas, and others.

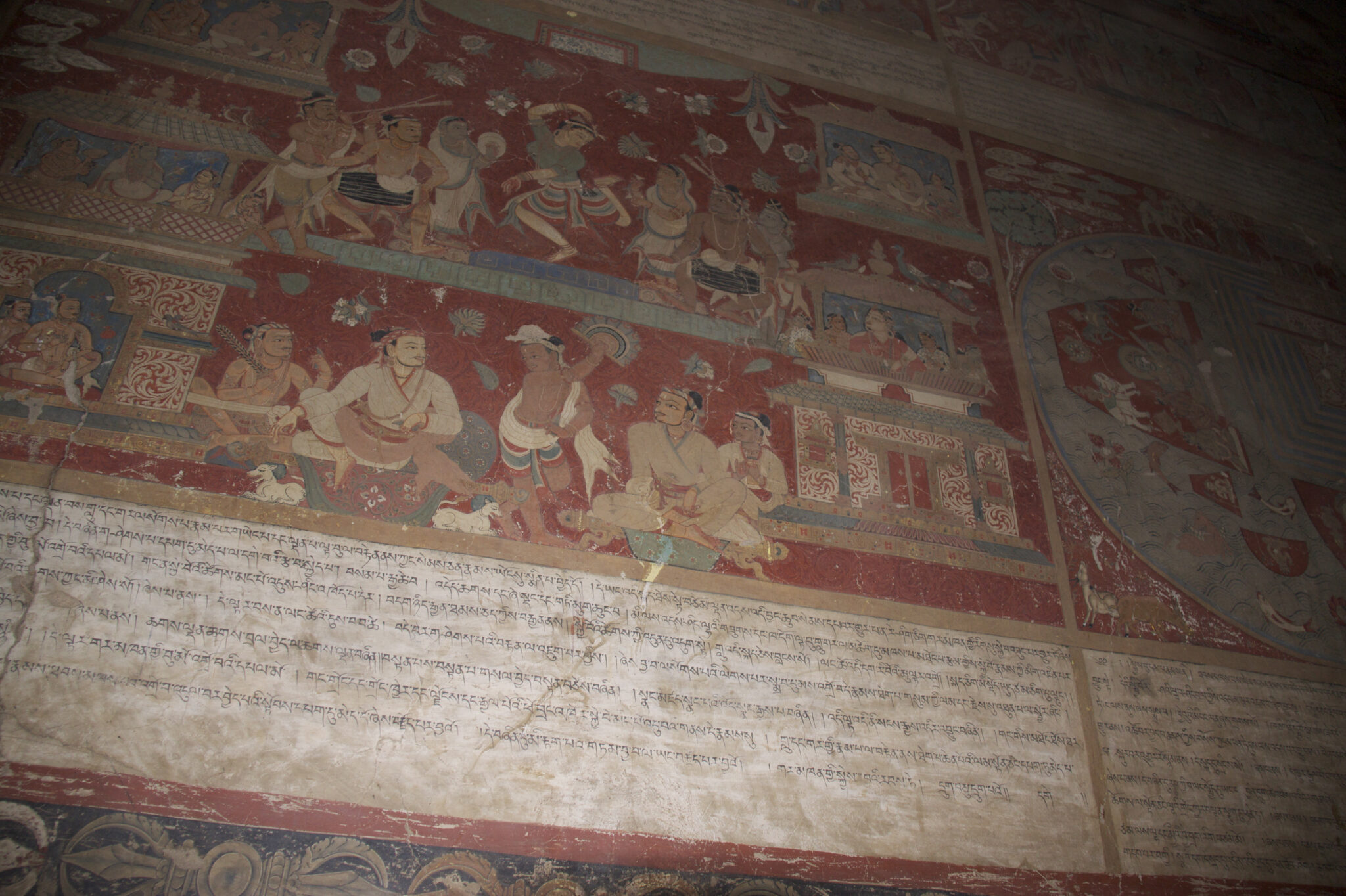

Jatakas are a genre of Buddhist literature about the previous lives, or incarnations, of Buddha Shakyamuni, sometimes as an animal before he attained enlightenment. With lively stories that illustrate the importance of compassion and cultivating karmic merit, these stories are a favorite topic of Buddhist illustration.

The Newars are traditional inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal. The Newars speak a Tibeto-Burman language (Newari) and practice both Hinduism and Buddhism. The Newars are inheritors of one of the oldest and most sophisticated urban civilizations of the Himalayas, and Newar arts and artisans have been celebrated all across the Himalayan world since the Licchavi period.

A practice of hiring and commissioning artists to create works of art. In religious context patrons were often rulers, religious leaders, as well as ordinary people. (see also donor)