In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a being who has made a vow to become a buddha or awakened. In the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, many bodhisattvas are understood as deities with enormous powers who delay their final enlightenment, remaining in the phenomenal world to help suffering beings. Among such great bodhisattvas are Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Maitreya.

In Buddhism and Bon, a buddha is understood as a being who practices good deeds for many lifetimes, and finally, through intense meditation, achieves nirvana, or ”awakening”—a state beyond suffering, free from the cycle of birth and death. “The Buddha” of our age is Shakyamuni, or Siddhartha Gautama. He is considered the founding teacher of the religion we call Buddhism. The buddha prior to Shakyamuni was called Dipamkara, and the next buddha will be Maitreya. These are known as Buddhas of the Three Times. Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhists believe that there are infinite buddhas in infinite universes, who have many bodies or emanations. Other important buddhas include Amitabha, Vairochana, Bhaishajyaguru, Maitreya, and many more.

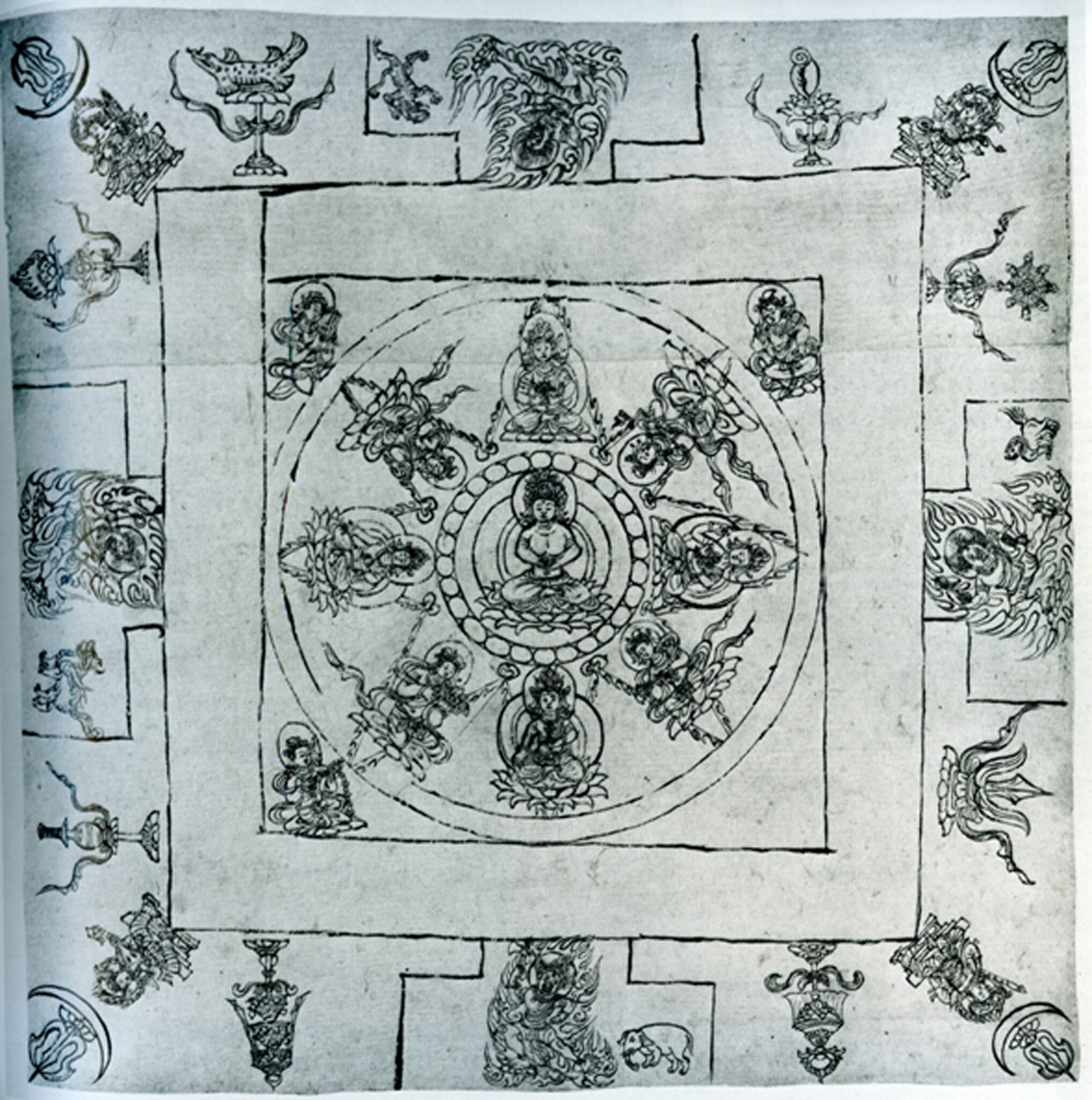

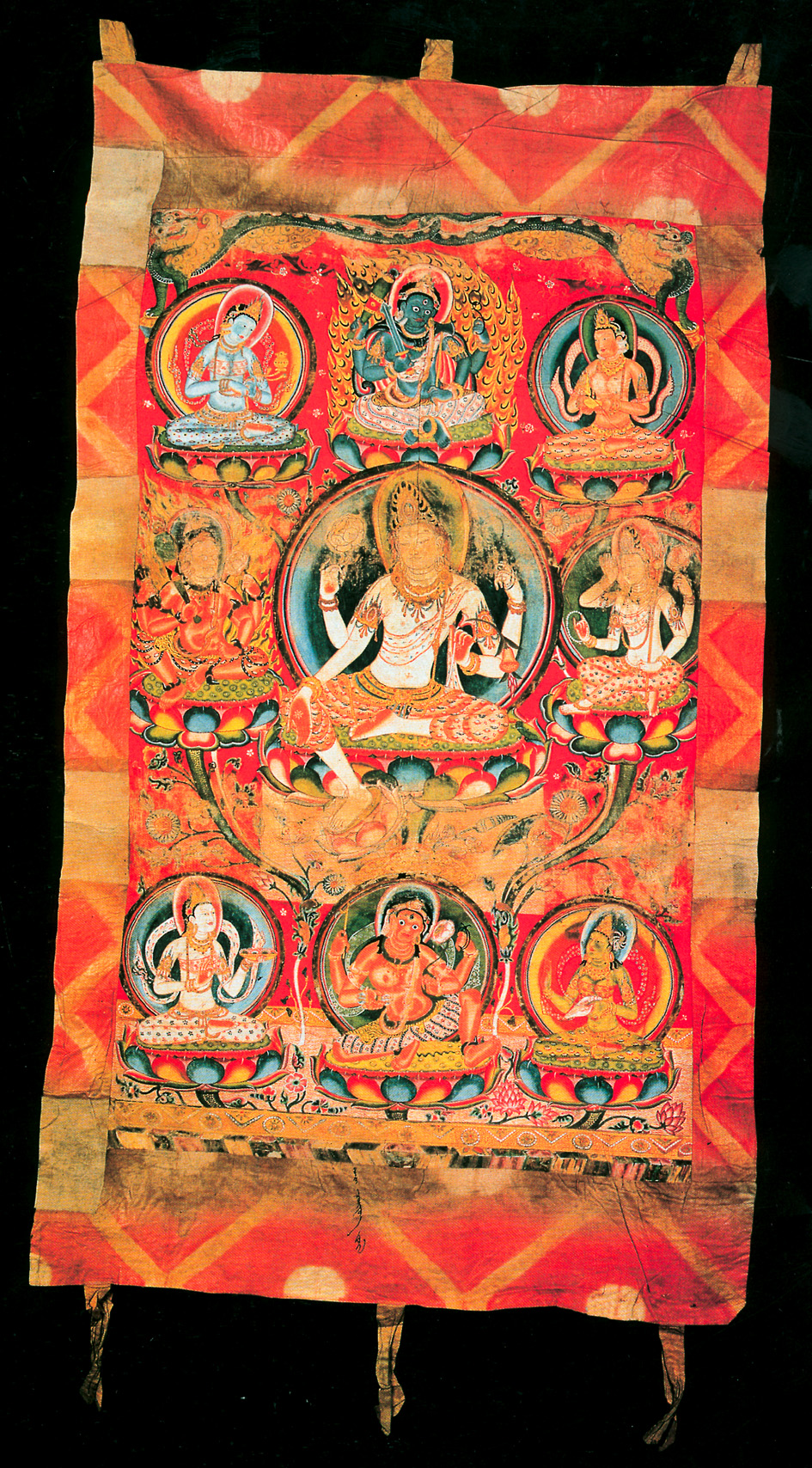

In the Himalayan context, iconography refers to the forms found in religious images, especially the attributes of deities: body color, number of arms and legs, hand gestures, poses, implements, and retinue. Often these attributes are specified in ritual texts (sadhanas), which artists are expected to follow faithfully.

In Buddhism, merit is accumulated positive karma, or positive actions, that lead to positive results, such as better rebirths. Buddhists gain merit by reciting mantras, donating to monasteries and those in need, performing pilgrimages, commissioning artworks, reproducing and reciting Buddhist texts, and other deeds with good intentions. It is believed that merit can also be transferred to others through rituals performed to gain merit for deceased family members help them achieve a better rebirth. Merit making is an important motivation for positive ritual action, and is a prerequisite for success of religious and even secular activity.

“Silk Roads” is a term broadly used to describe the long-distance trade routes across Central Asia that connected the Indian Subcontinent with East Asia and the Mediterranean world. These trade routes were highly important in transmitting both art and ideas across the Asian continent, including the Buddhist religion. There were many “silk roads”—some crossed the deserts of Central Asia, other maritime routes also connected Europe, the Middle East, Africa, South, Southeast, and East Asia.

The Tibetan script is used to write the Tibetan language, as well as several other smaller Himalayan languages. Based on the Brahmi script used in the Gupta Empire in India, the Tibetan script was developed under the Tibetan Empire in the seventh century and is credited to minister Tonmi Sambhota (b. 619?). Two important forms of the Tibetan script are “Uchen” (Tib. “having a head”), a standard type used in printed texts, and “Umey” (Tib. “headless”), a cursive form sometimes used in manuscripts. There are many other cursive and decorative forms of the script.