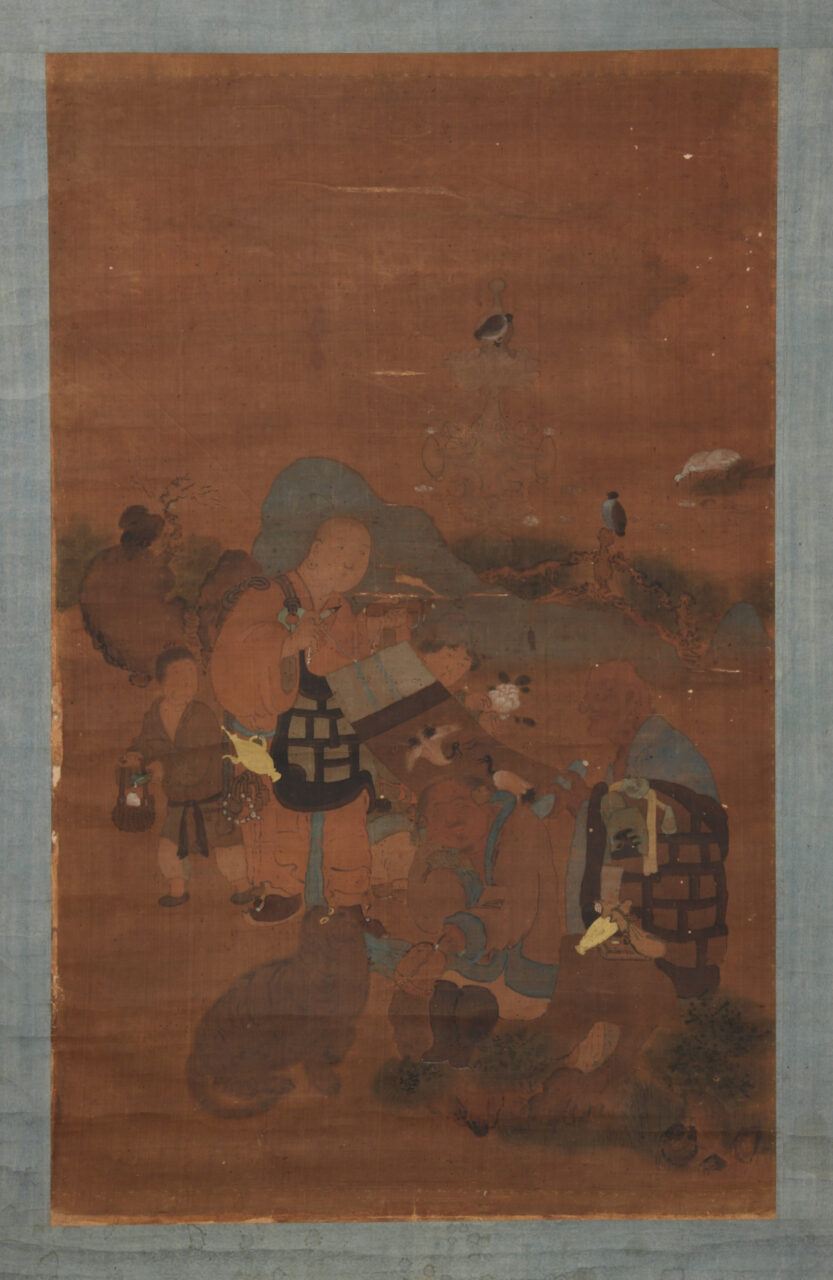

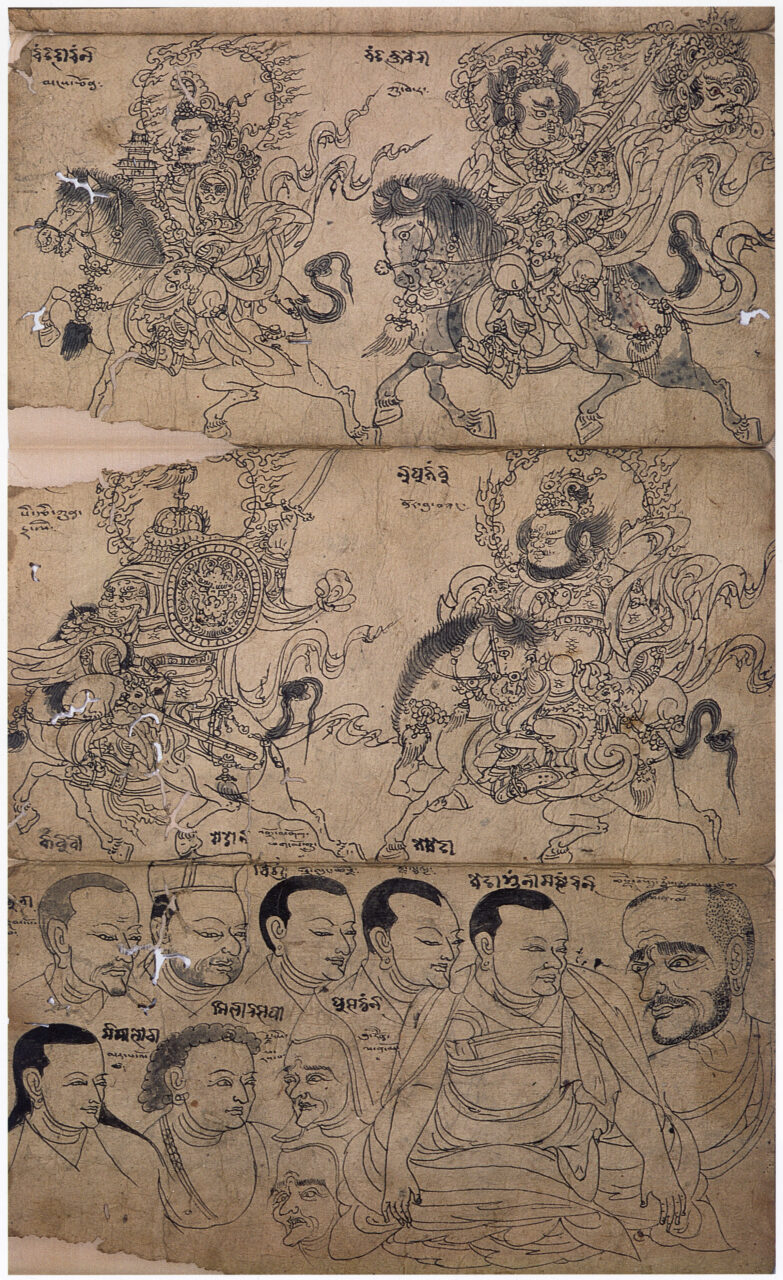

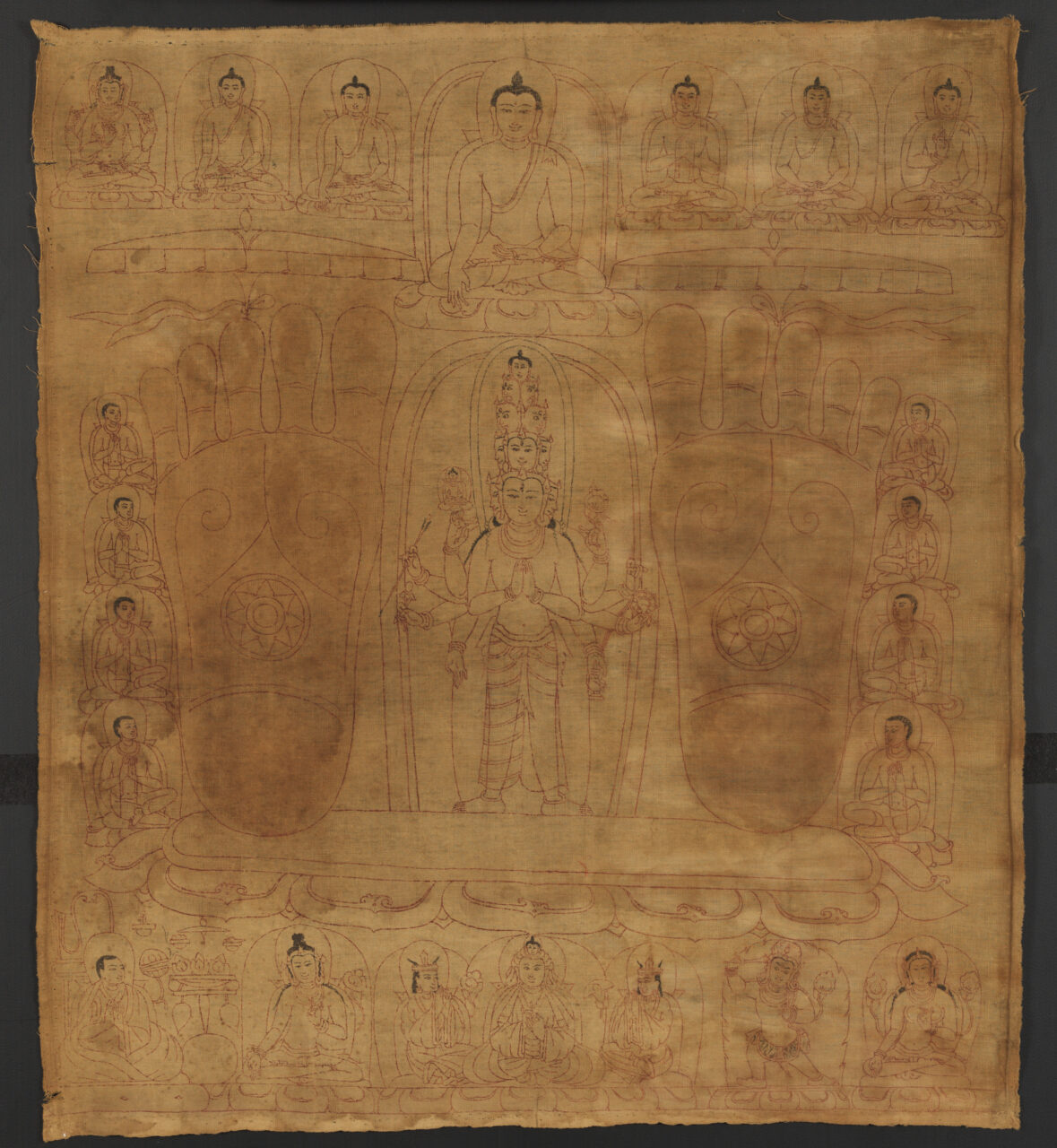

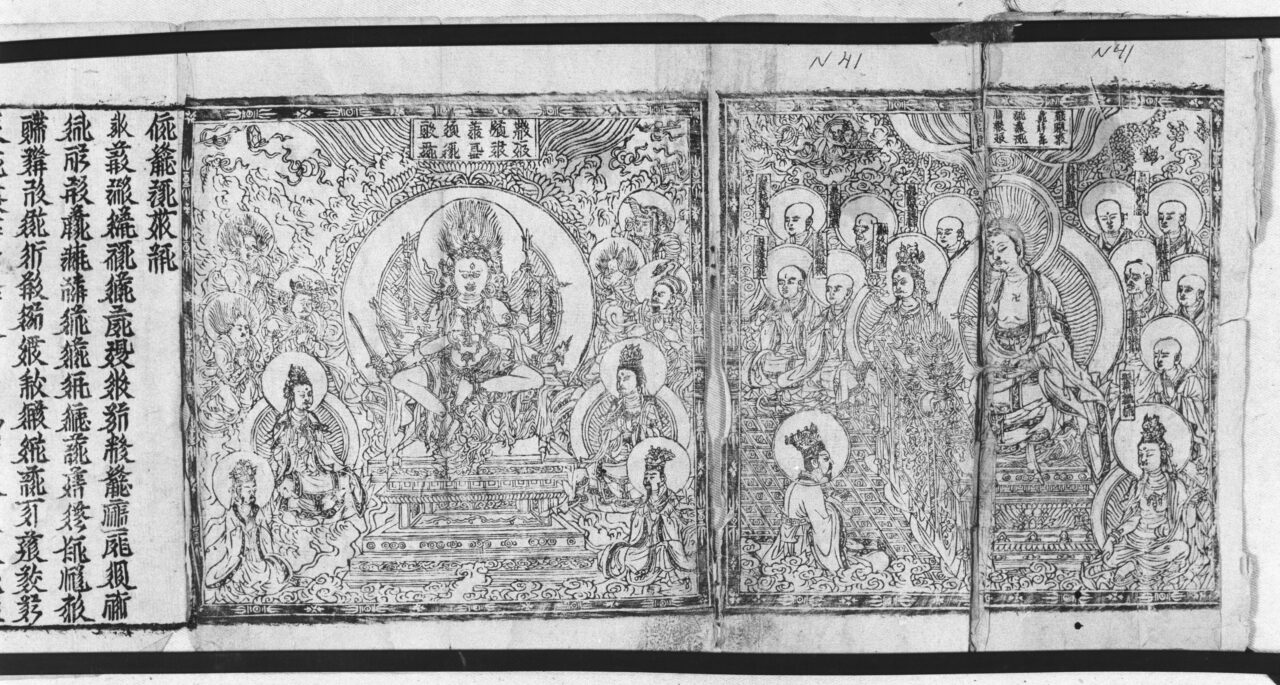

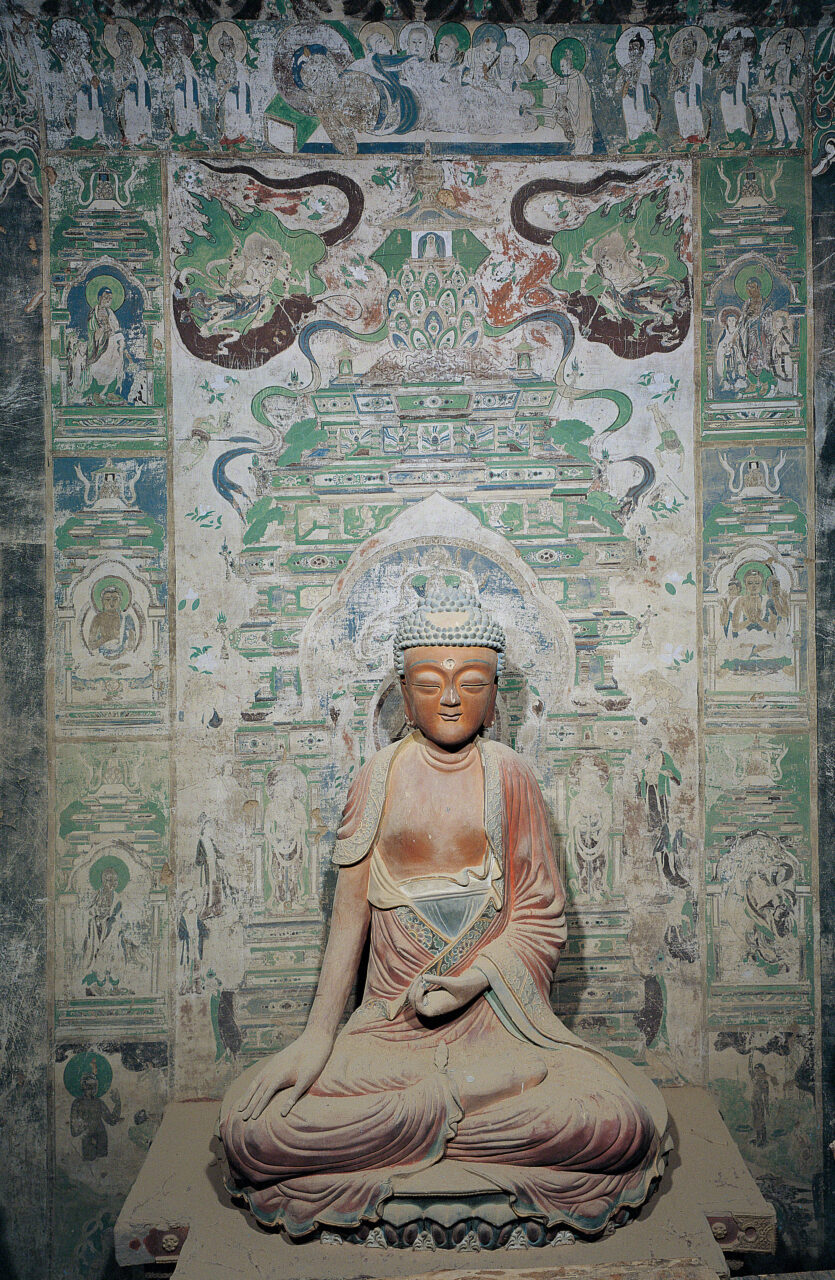

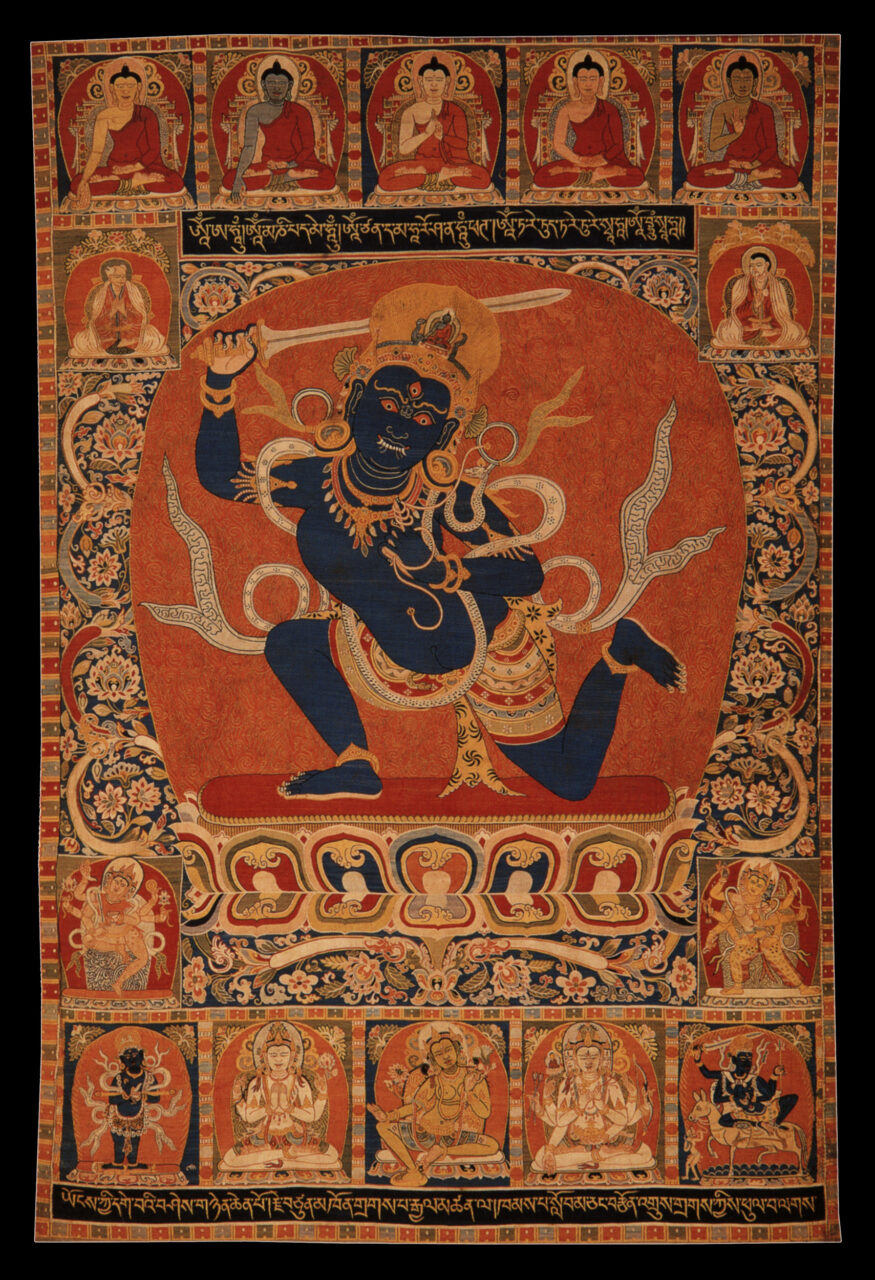

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a being who has made a vow to become a buddha or awakened. In the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, many bodhisattvas are understood as deities with enormous powers who delay their final enlightenment, remaining in the phenomenal world to help suffering beings. Among such great bodhisattvas are Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Maitreya.

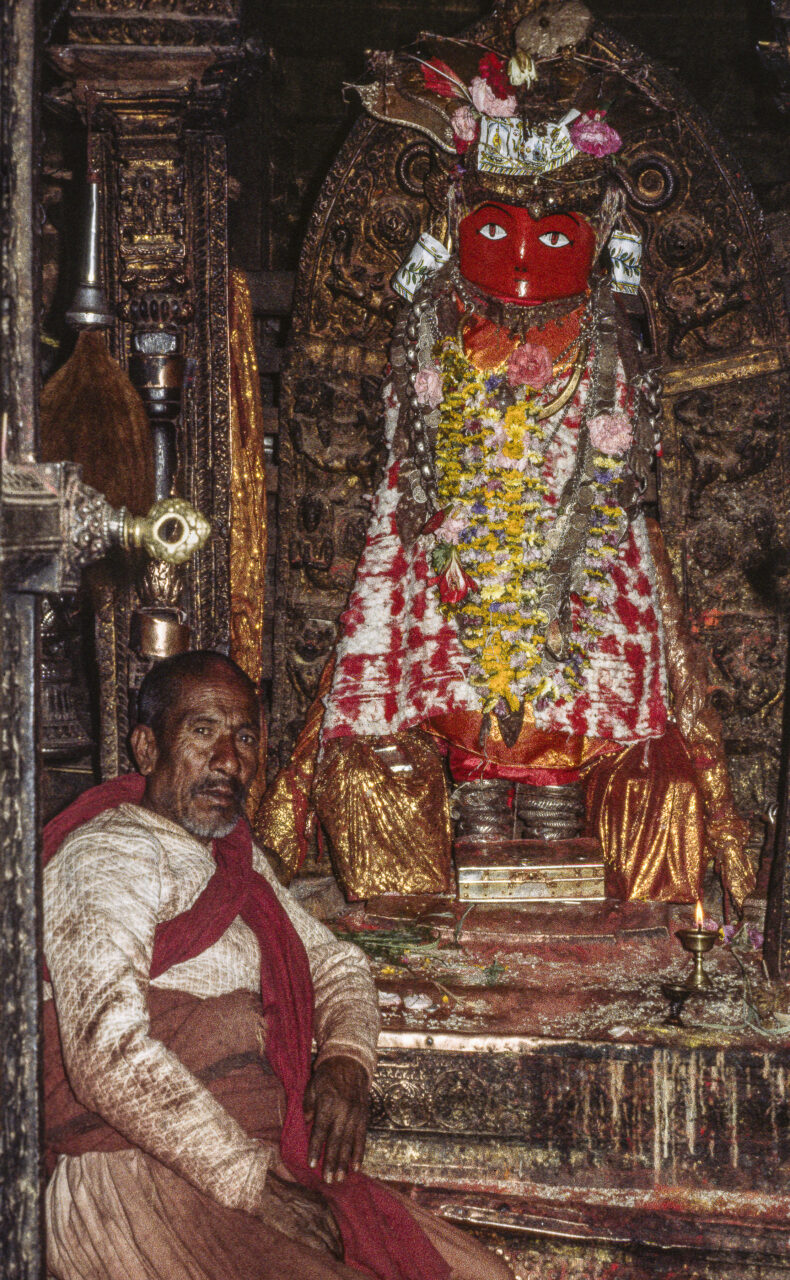

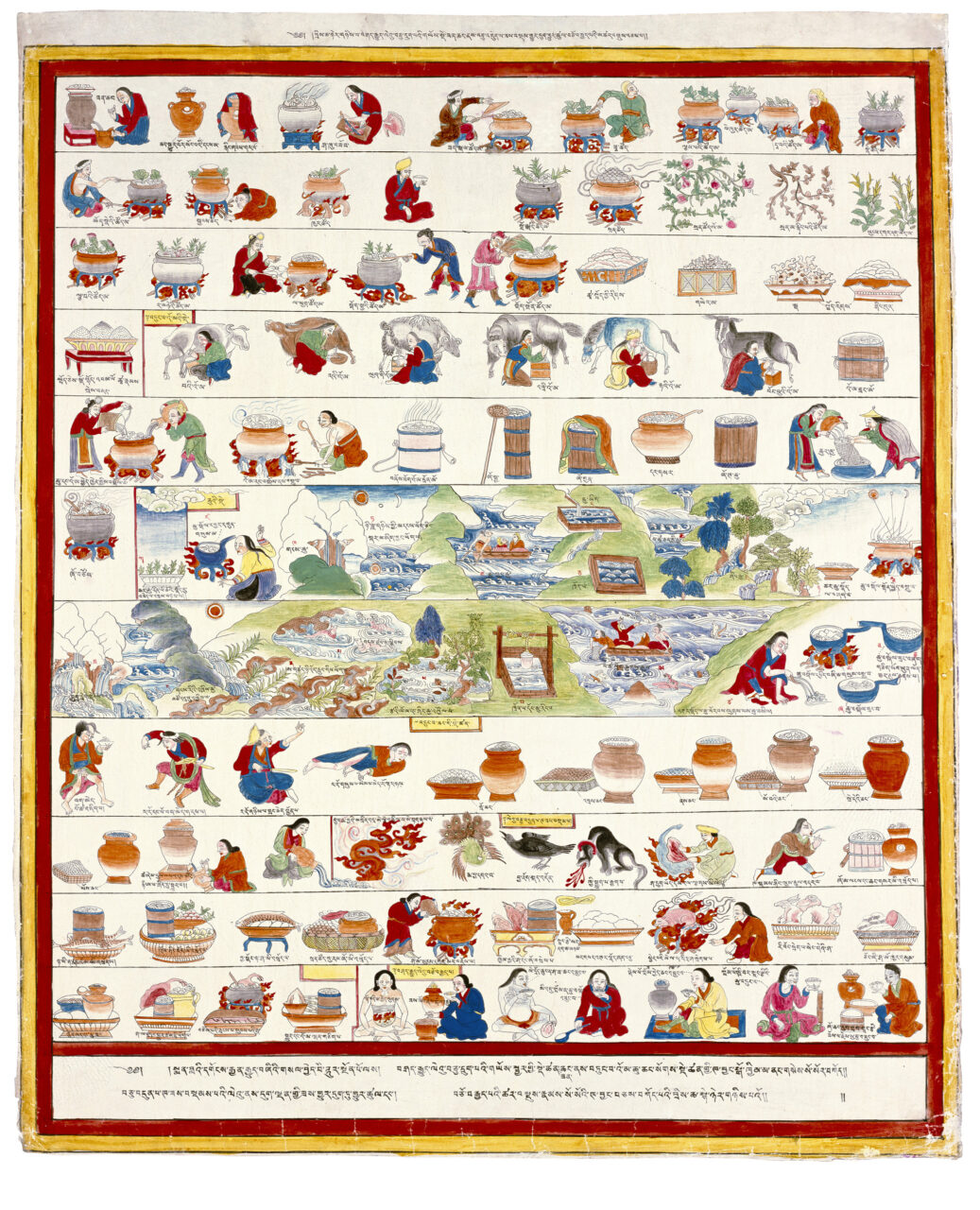

In Buddhist context, donor is a person who contributes to or commissions a religious work of art. This act is intended to increase merit on behalf of the benefactor and is dedicated to the benefit of all. It is also usually done for a specific purpose, such as longevity, prosperity, or well-being; to advance religious practice; or to ensure a good rebirth of a deceased relative, teacher, or friend. A similar practice is also known in Hinduism and Bon.

Inlay is a decorative technique of creating a depression in a surface and then filling it with some other material. Metal can be inlaid with precious stones or glass, or more precious forms of metal, for instance, brass inlaid with silver and copper. Wood can be inlaid with silver, or other metal and conch. Tibetans tend to favor turquoise inlay while the Newars employ a range of colored glass and semi-precious stones.

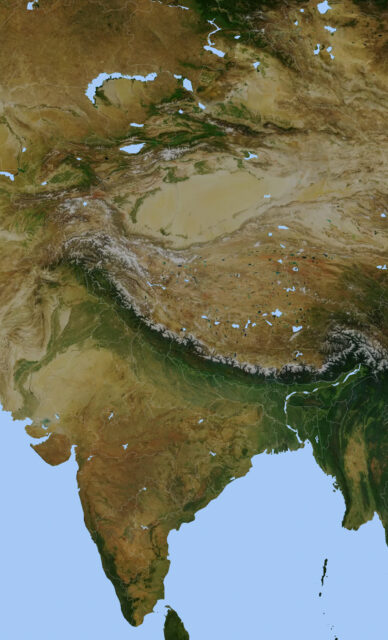

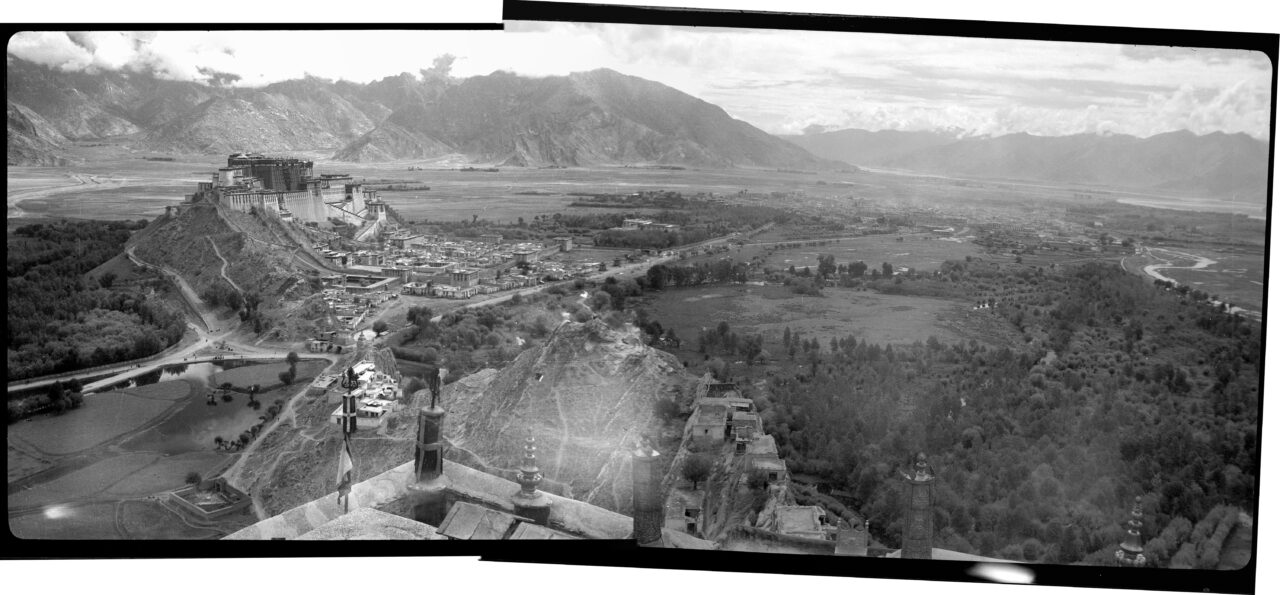

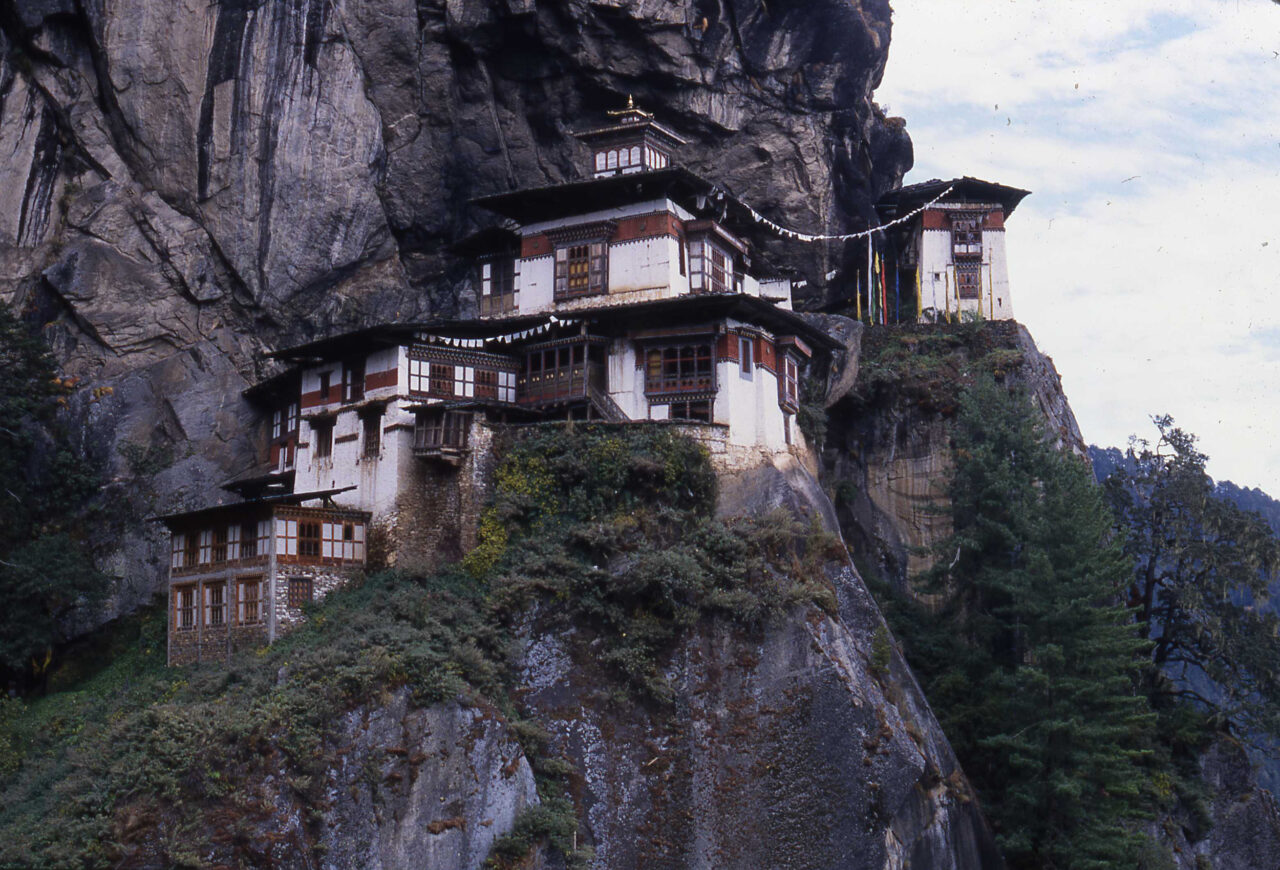

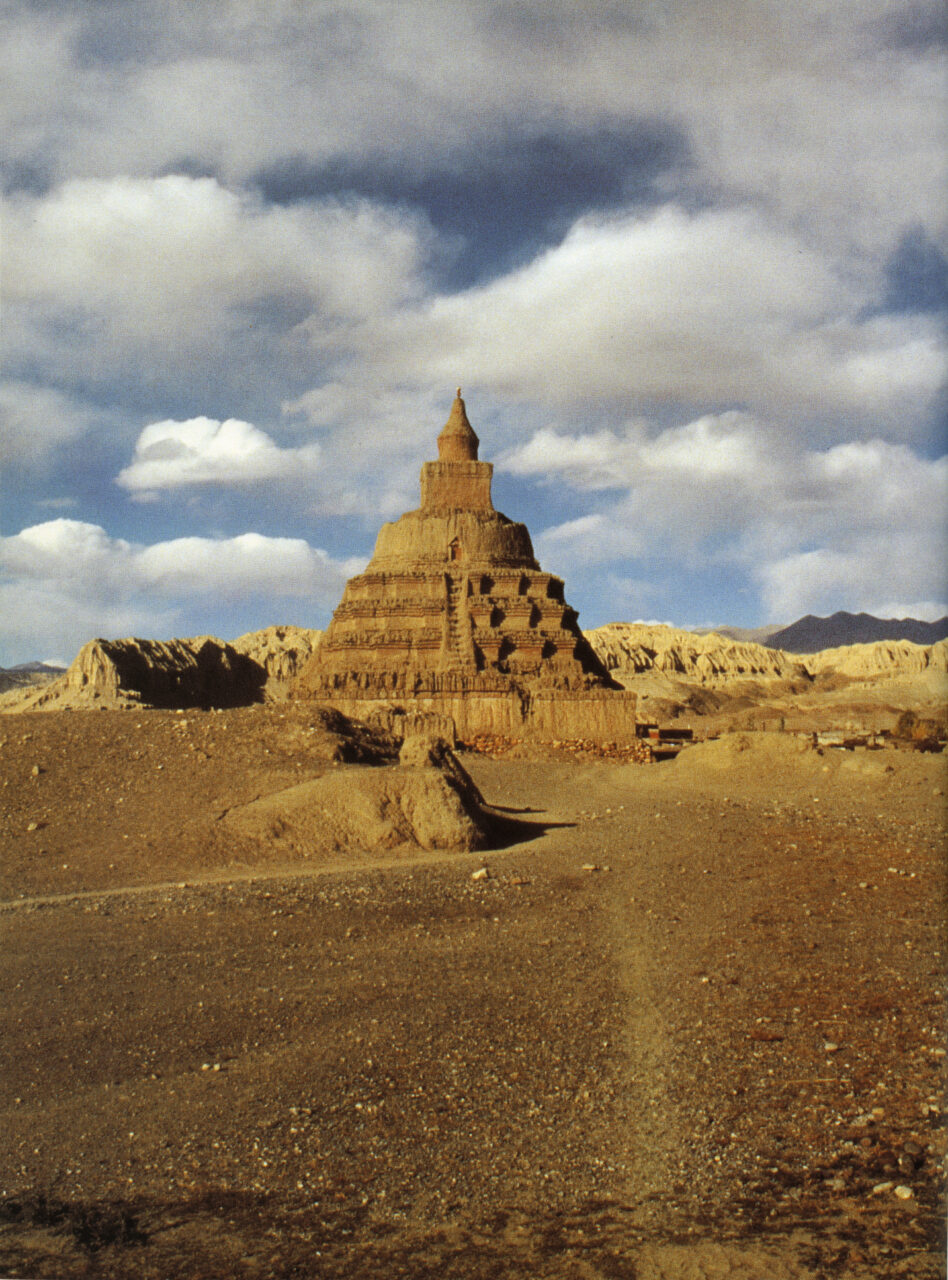

In Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain cosmologies Mount Meru is a mountain at the center of the world, the peaks of which contain heavens and divine realms. It is surrounded by many lakes, rings of mountains, and further out, the great ocean and four continents. Humans live on a southern continent called Jampudvipa. Buddhists interpret Jampudvipa corresponding to India, and Mount Meru is roughly equivalent to the Himalayas. Many Buddhists and Hindus identify Meru with Mount Kailash, a peak in western Tibet, as the focus of pilgrimage.

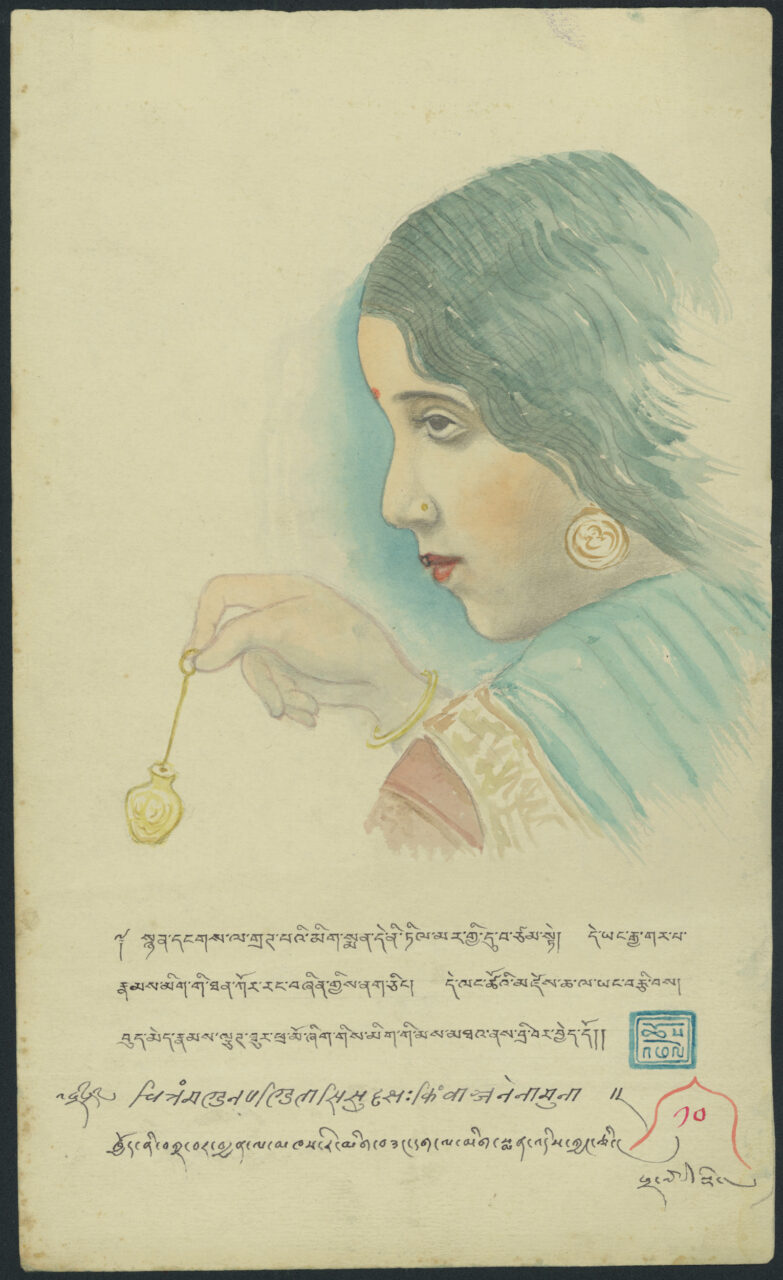

In Hinduism and Buddhism, mudras are ritual hand gestures made by deities, Buddhas, and other sacred figures. These hand gestures are important and relatively standardized parts of deities’ iconographies. Mudras are also performed by practitioners during rituals, allowing them to take on the bodily attributes of the deities.

The Palola Shahis were a Buddhist kingdom that flourished between the sixth and eighth centuries CE in what is now the Hunza Valley of northern Pakistan. Military control over this strategic kingdom was contested between the Tang Dynasty of China and the Tibetan Empire, and most of what we know about the Palola Shahis comes from the chronicles of these outside forces, as well as the travel accounts of East Asian pilgrims. The Palola Shahis are known for their patronage of elegant bronze sculptures, a sculptural tradition shared with the nearby Swat Valley and Kashmir.