In Buddhist context, donor is a person who contributes to or commissions a religious work of art. This act is intended to increase merit on behalf of the benefactor and is dedicated to the benefit of all. It is also usually done for a specific purpose, such as longevity, prosperity, or well-being; to advance religious practice; or to ensure a good rebirth of a deceased relative, teacher, or friend. A similar practice is also known in Hinduism and Bon.

In the Himalayan context, iconography refers to the forms found in religious images, especially the attributes of deities: body color, number of arms and legs, hand gestures, poses, implements, and retinue. Often these attributes are specified in ritual texts (sadhanas), which artists are expected to follow faithfully.

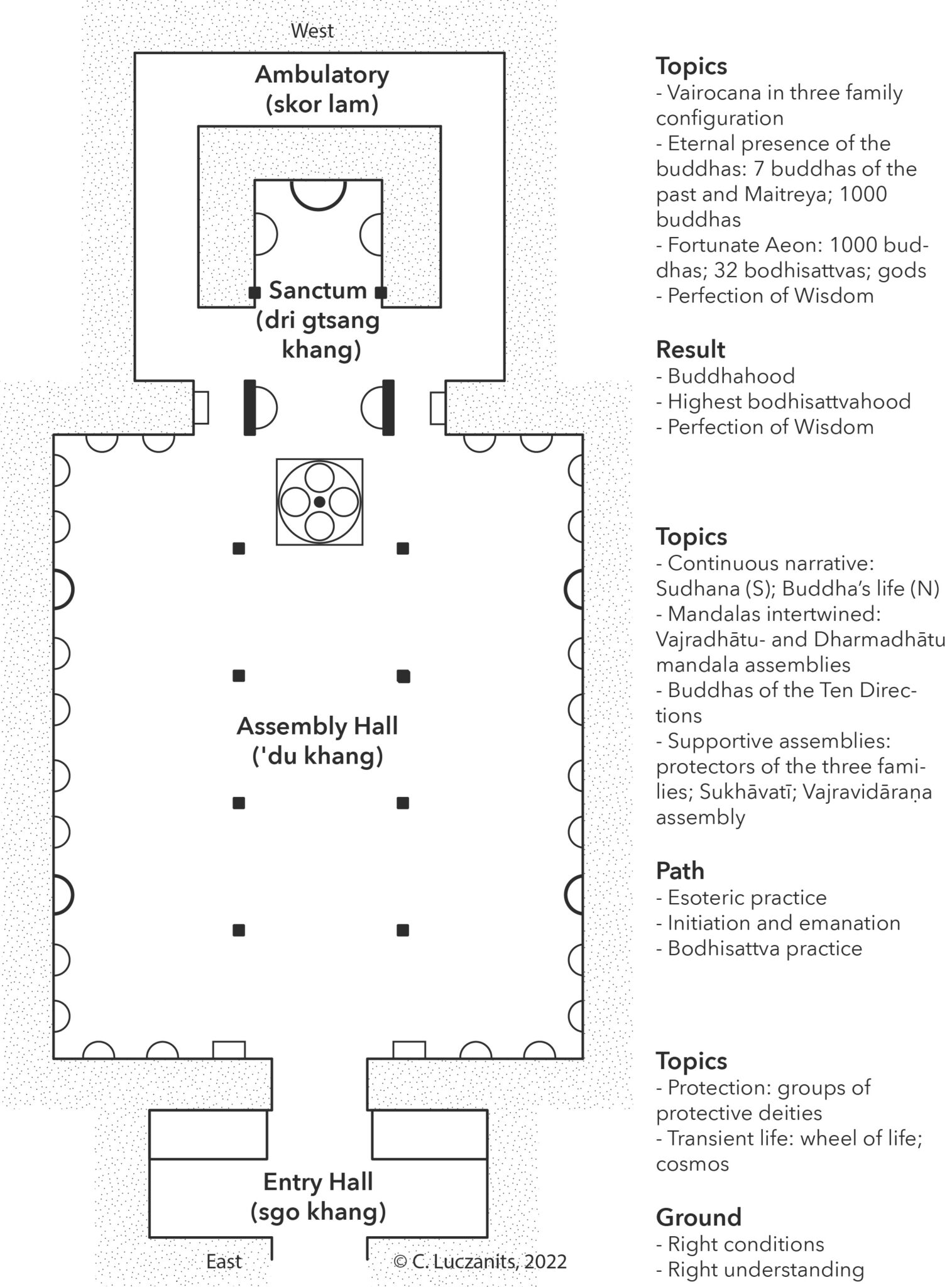

In Vajrayana Buddhism or Bon, a mandala refers to a cosmic abode of a deity, usually depicted as a diagram of a circle with an inscribed square that represents the deity enthroned in their palace, surrounded by members of their retinue. Mandalas can be painted, three-dimensional models, architectural structures, such as temples or stupas, or composed as arrangements of images within a temple. The instructions for creating and visualizing mandalas are usually found in ritual texts, such as tantras and sadhanas. Mandalas can be used in initiation ceremonies, visualized by a practitioner as part of deity yoga, consecrated and used to represent the divine presence within ritual space, offered to the deities as representations of the entire universe. A similar concept in Hinduism is a yantra.

A monastery is a place where monks live, study, and perform ritual. It includes temples and other structures. Monasteries are central to Buddhism, and are also important in Bon, Hinduism, and Daoism. In Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian areas, some monasteries are enormous, wealthy, and powerful institutions, with branches of satellite monasteries forming networks across regions, often with thousands of monks, many decorated chapels, and huge holdings of land. Other monasteries, called hermitages, can be extremely simple, little more than a cave where hermits meditate. Generally, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery will have an assembly hall, several temples (Tib. lhakhang) for worship of specific deities, a protector chapel, as well as monks’ accommodations. A related institution in Newar Buddhism are the baha and bahi.

In the Vedas, vajras are the indestructibly hard thunderbolts that Indra hurls at his enemies. Over time, the vajra became the name for a type of ritual weapon, with a handle at the center and a five-pronged point at each end. Vajras are a central image in and symbol of tantric forms of Buddhism, which are often called “Vajrayana” or the “Vajra Vehicle.” Vajrayana ritualists use vajras (representing active compassion or method) often paired with a bell (representing wisdom) in practices of deity yoga. The Tibetan word for a vajra is “dorje,” meaning “Lord among stones.”

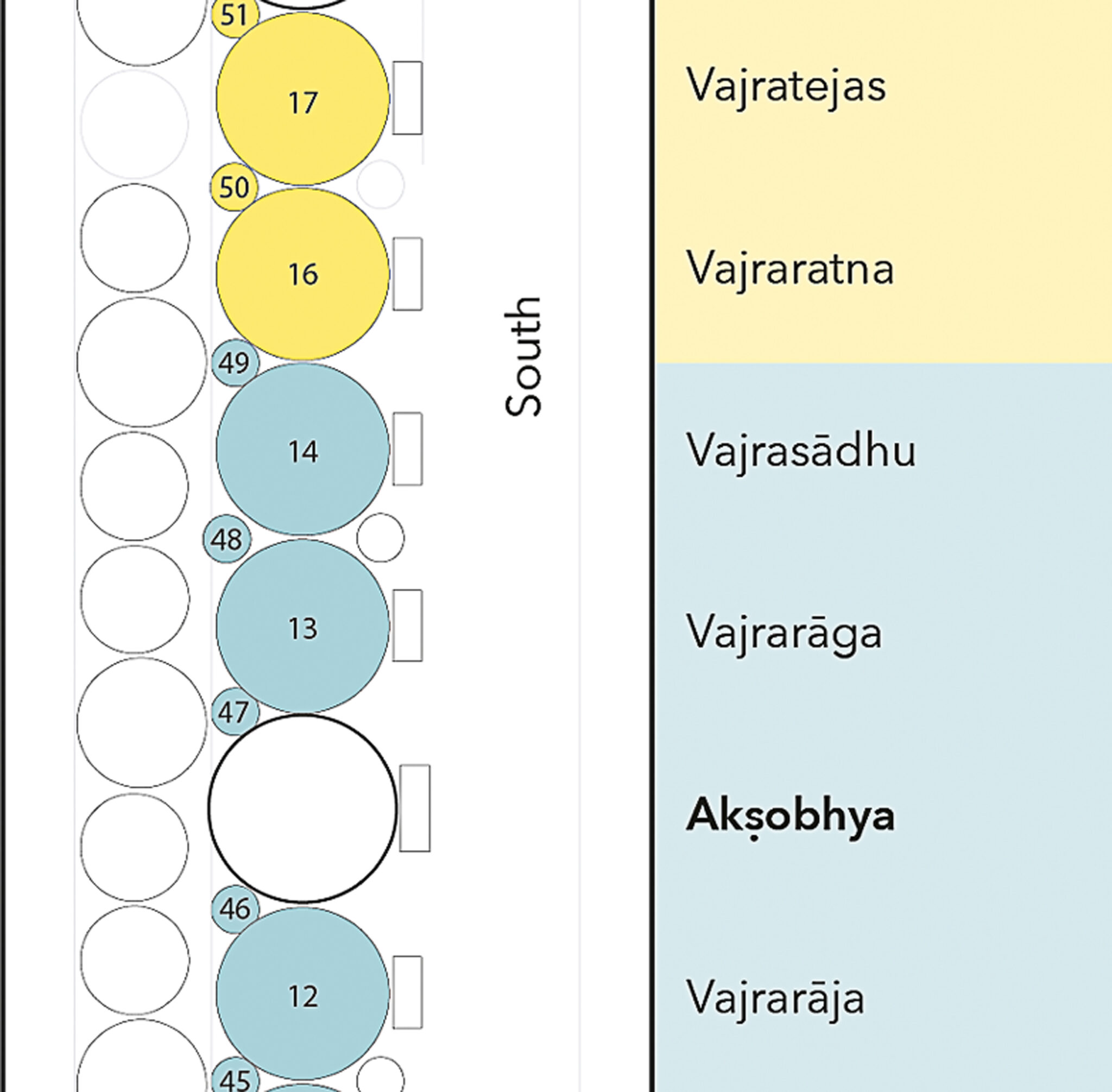

The Vajradhatu refers to the ritual space described in the Yoga tantras and represented in mandalas of the five buddhas of the five families, centered on Vairochana.