Jokhang Temple, Lhasa

Lhasa, U region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China) ca. 620–640Jokhang Temple in 2005; Lhasa, U region, central Tibet (TAR, China); photograph by Meiqianbao

Jokhang Temple in 2005; Lhasa, U region, central Tibet (TAR, China); photograph by Meiqianbao

Jokhang Temple in 2005; Lhasa, U region, central Tibet (TAR, China); photograph by Meiqianbao

Tibetologist and art historian Amy Heller sorts legend from fact in the history of Tibet’s holiest temple. Believed to have been founded in the seventh century by emperor Songtsen Gampo, this widely revered temple has survived centuries of civil disturbance, fires, disrepair, and renovations to remain the heart of Lhasa for pilgrims, devotees, and tourists to this day.

In Buddhism and Bon, a buddha is understood as a being who practices good deeds for many lifetimes, and finally, through intense meditation, achieves nirvana, or ”awakening”—a state beyond suffering, free from the cycle of birth and death. “The Buddha” of our age is Shakyamuni, or Siddhartha Gautama. He is considered the founding teacher of the religion we call Buddhism. The buddha prior to Shakyamuni was called Dipamkara, and the next buddha will be Maitreya. These are known as Buddhas of the Three Times. Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhists believe that there are infinite buddhas in infinite universes, who have many bodies or emanations. Other important buddhas include Amitabha, Vairochana, Bhaishajyaguru, Maitreya, and many more.

Circumambulation means walking around something. Himalayan Buddhists often circumambulate as a form of veneration and generate/accrue merit by walking in a clockwise direction around stupas, monasteries, or sacred mountains. Bonpos do the same thing, except counter-clockwise.

Jowo is a Tibetan term of respect for a deity, most often referring to an image of the Buddha. The most famous is the Jowo Rinpoche, the main image of the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa. There are other sacred Jowo images, such as the Jowo at Erdeni juu Monastery in Mongolia.

The Newars are traditional inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal. The Newars speak a Tibeto-Burman language (Newari) and practice both Hinduism and Buddhism. The Newars are inheritors of one of the oldest and most sophisticated urban civilizations of the Himalayas, and Newar arts and artisans have been celebrated all across the Himalayan world since the Licchavi period.

In the early seventh century, a line of kings from the Yarlung Valley united disparate people on the Tibetan Plateau into a powerful, centralized state. With their capital at Lhasa, these kings proclaimed themselves emperors, or tsenpo. Their armies conquered much of the Himalayas, Central Asia, and western China. Tibetans developed a written script for the Tibetan language and Buddhism was adopted as a state religion. The conversion to Buddhism was contested by an indigenous group of ritualists called Bon, creating political turmoil. After the assassination of emperor Langdarma in 842, the Tibetan empire fragmented and collapsed. Nevertheless, the myths and memories of the empire continue to be a central part of Tibetan identity.

The Jokhang is undoubtedly the most revered temple in Lhasa, even in all of Tibet. Its role is so crucial that the urban development of Lhasa has centered around the Jokhang for over a millennium. Today the Jokhang is an extensive complex of temple buildings with courtyards, monks’ quarters, offices, and kitchens. It has been constructed in several stages since Lhasa became the Tibetan capital during the seventh century after Emperor Songtsen Gampo (ca. 605-649), through numerous military campaigns to unify Tibet and expand Tibetan territory, managed the feat of confederating tribes.

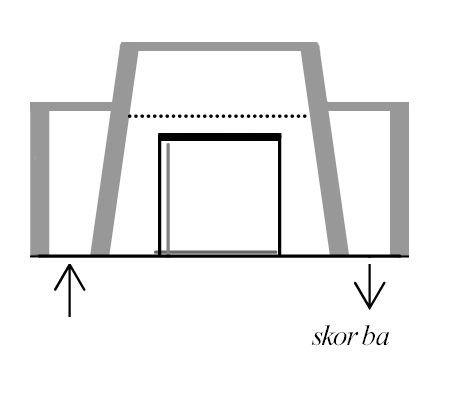

Although shrouded in entangled myths and traditions, the history of the successive construction phases of the Jokhang may be clarified by a comparison with the architecture of Trandruk, Thundering Falcon, Tibet’s earliest temple in the Valley; Ramoche in Lhasa; and the Katsel temple just north of Lhasa. What is striking in these three temples attributed to the imperial period is the tall trapezoid structure at the center: the principal chapel with a roof twenty to twenty-three feet (six to seven meters) high. The inclined walls of the sides of the trapezoid afford protection in the earthquake-prone zone of the Himalayas, for such walls are broader and heavier at the base. Each trapezoid structure is surrounded by a narrow corridor for (kora) (figs. 2 and 3).

Tower diagram of Katsel temple, near Lhasa, U region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China); 7th century construction; diagram by Guntram Hazod

Tower diagram of Katsel temple, near Lhasa, U region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China); 7th century construction; diagram by Guntram Hazod

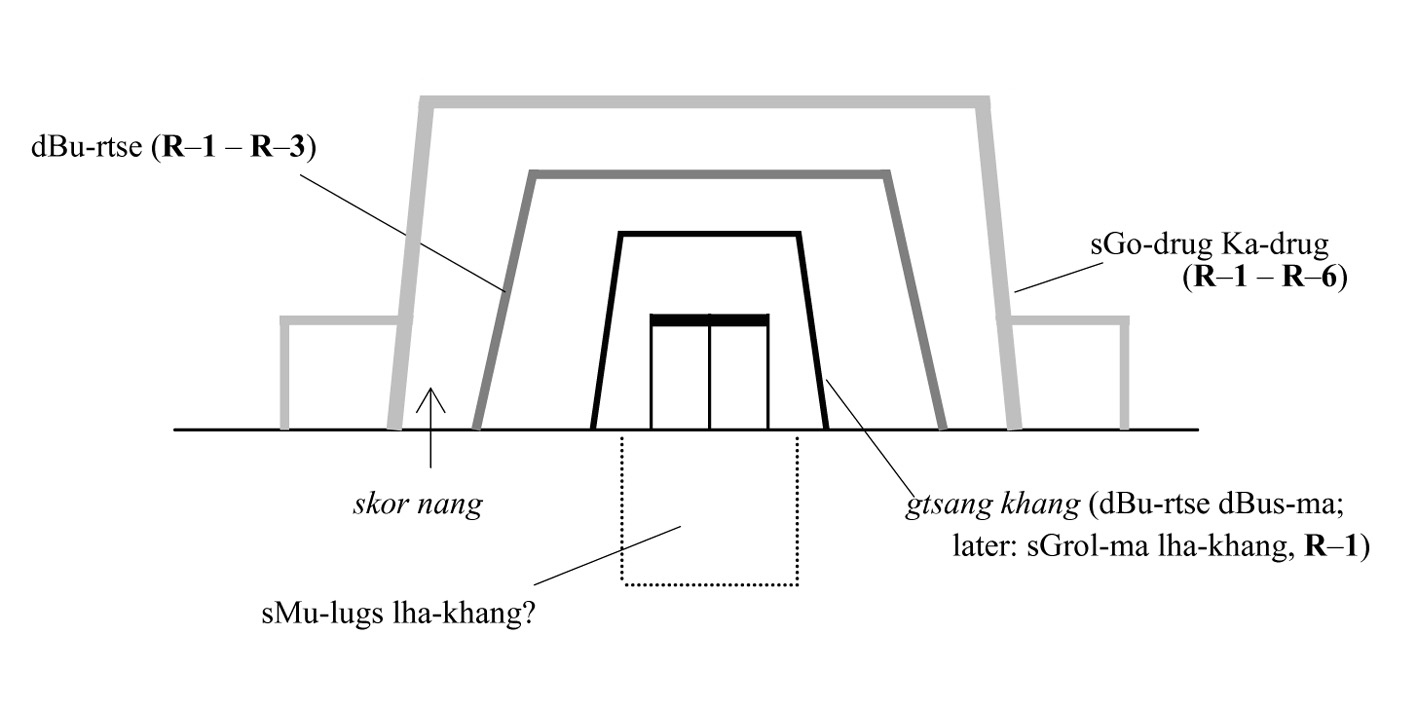

The construction of this central structure destined to become the chapel, with the procession corridor forming the two adjacent chapels, initially extended eastward and upward to another floor, doubling it in volume. Then, surrounding this inner square, the nangkor, or inner procession corridor, was added between the tenth and thirteenth centuries. During the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries, the inner courtyard was converted into an assembly hall, a third floor was added, and three of the four gilded copper roofs were constructed. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Jokhang was completed with two more outer courtyards, four new entrances, a new main entrance porch, and an outdoor assembly square (fig. 4).

Plan of the Jokhang Temple, Lhasa, U region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China); image after Knud Larsen and Amund Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas, London: Serindia Publications, 2001, 114

Reflecting on these phases, it is apparent that the Jokhang evolved toward the architecture of a vihara, a square Indian temple with a cloistered courtyard, fifty-nine by fifty-nine feet (eighteen by eighteen meters), surrounded by small chapels or monks’ cells. Precisely when this occurred is not certain. Was this during the period of the reign of Songtsen Gampo or later generations? No data from Songtsen’s lifetime confirms his role as a Buddhist sovereign. Historic records describe his military prowess and political acumen.

In 641, Songtsen effectively installed the King Narendradeva (r. 643–679) on the throne of Nepal. Following a coup d’état in Nepal, Narendradeva and his court had taken refuge in Lhasa since about 624. According to later Tibetan tradition, the foundation of the Jokhang is attributed to Songtsen assisted by a Nepalese princess, known in Tibetan as “royal lady” Tritsun, who may have been with Narendradeva’s court in Tibet. Although the historical existence of the Nepalese princess has long been questioned, ample evidence supports active exchanges—political, cultural, and commercial—between Tibet and Nepal at this time. The earliest wooden carved lintels of the Jokhang are to be understood as a concrete reflection of Newar artists and artisans working in Tibet during the seventh to eighth century (fig. 5).

Later Tibetan historical tradition magnifies the promotion of by Songtsen, the Nepalese princess, and a very young Chinese princess who arrived in Lhasa in 641 and married Songtsen in 646, three years before he died. The early construction of several Buddhist temples in Tibet has been related to geomantic criteria attributed to the Chinese bride, who survived long after Songtsen’s death; her funeral is recorded in 683–684 CE.

Analysis and surveys by architectural historians confirm that ancient models of temples such as Tibet’s first Buddhist temple, Tandruk, evolved into a vihara structure like the Jokhang. The vihara was a model in Gupta India (320–600), Cave 2 at (late sixth century) (fig. 6), and still in use under the Pala dynasty (750–1161). Other early temples like the Ramoche, attributed to the Chinese bride, and Katsel also conform to the early architectural models. Tandruk and Katsel figure among the thirteen temples mapped on an elaborate geomantic schema of concentric zones centered around the Jokhang—even extending as far southeast as present-day Bhutan and east to Kham—all attributed to Songtsen by later tradition.

indiavideodotorg, "Ajanta Cave No.2 Aurangabad, Maharashtra," YouTube, April 9, 2012, 0:59, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GtfJyA2KbmE.

Luckily, a clear picture emerges by virtue of historic edicts and, above all, the Tibetan inscriptions carved on stone pillars erected at the founding of temples in the eighth and ninth centuries, such as Samye in 779 and Karchung (ca. 800–815), which record the existence of many Buddhist institutions throughout Tibet at the time. Emperor Tri Songdetsen (742–ca. 800) declared Buddhism the official religion of the in 781, swearing to preserve Buddhism and actively support Tibetan monks. The Old Tibetan Chronicle, probably compiled around 800–840, was the first to describe the flourishing of Buddhism in reference to the reign of Tri Songdetsen: “The incomparable religion of the had been received and there were sanctuaries in many parts of the land.”

Civil disorder in the mid-ninth century led to the dissolution of the Tibetan Empire, and the scions of the dynasty fled central Tibet. In about 1000 a revival of Buddhism was promoted at in western Tibet. The flame of Buddhism was rekindled in central Tibet in the mid-eleventh century, when Tibetans coming from both western and eastern Tibet, as well as Indian and Nepalese monks and scholars, resumed teaching.

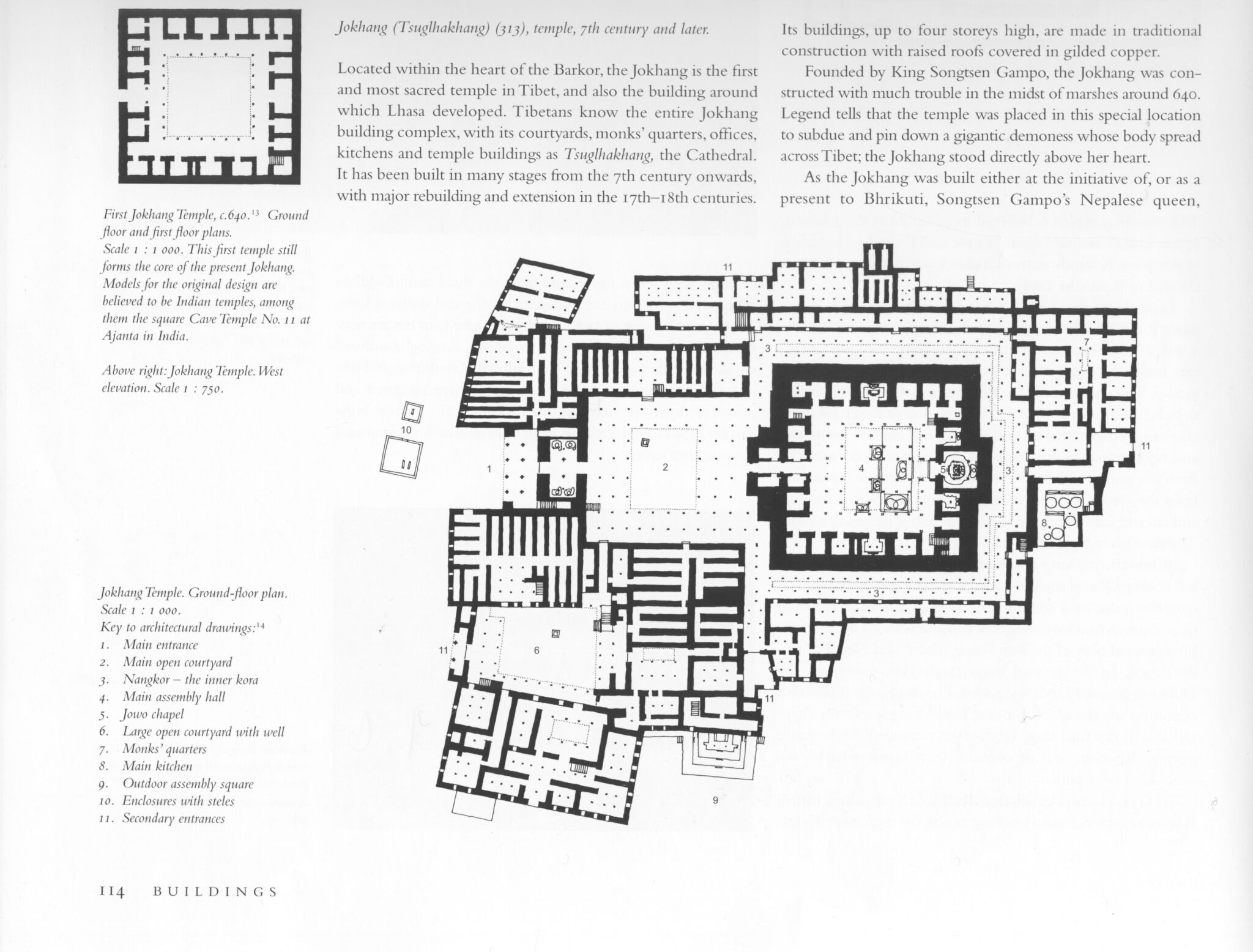

Zangkar Lotsawa, the Translator of Zanskar, studied Buddhism in Toling. After studies in Kashmir, he traveled toward Lhasa, where in 1076 he initiated a program of major renovation inside the Jokhang resulting in the present layout of the ground floor and second floor. He organized renovations inside the Jowo chapel, including the addition of the twenty-foot-tall (six meters) enthroned in clay, called Tubpa Gangchen Tsogyel (Vairochana of the Glacier Lake) (fig. 7), accompanied by six male and six female standing behind him against the walls. The “Jowo,” the cast-metal sculpture of Shakyamuni, is enthroned in the middle of the chapel. Mural paintings, such as that of (fig. 8), reflecting the style of Pala India, are also from that time.

Vairochana of the Glacier Lake; Jowo chapel, Jokhang Temple; Lhasa, U region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China); clay with pigments and matte gold; height approx. 20 ft. (6 m); photograph by Lionel Fournier

Vasudhara and Entourage; Zhelre Lhakhang, Jokhang Temple; Lhasa, U region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China); 11th century; pigments on clay primer, height approx. 51 1/8 in. (130 cm); photograph by Lionel Fournier

Detail of Jambhala and Vairochana showing a bodhisattva below Vairochana; Zhelre Lhakhang, Jokhang Temple; Lhasa, U region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China); photograph by Lionel Fournier

Although much damaged, the mural shows compositions with a main central (fig. 9), and scrolling floral/vegetal motifs accommodating the seated attendants in the lower register are lively. In a very different palette is a mural of as well as Vairochana and attendants on the walls of the Zhelre Lhakhang (literally, the chapel to revere the countenance of the Jowo Shakyamuni sculpture), situated on the upper level of the Jokhang. The bodhisattva seated below Vairochana shows the Pala characteristics of tiered crown with high piled chignon, the three-quarter view of the face with extended eye, the dip of the upper eyelid, and the elongated slender body proportions.

During a period of religious factionalism and great civil disturbance in Lhasa, the temple was damaged by a major fire in 1160. In the mid-thirteenth century, the Jowo sculpture was adorned by a sculpted throne back made by the Nepalese artist Anige (1245–1306) at the request of Shakya Zangpo, then acting abbot of . Subsequently, the Pakmodrupa, ruling from Nedong, continued fervent support of the Jokhang in the fourteenth century. During their reign, the rulers of the Yatse Kingdom in western Nepal commissioned gilt-copper roofs over two portions of the Jokhang, undoubtedly the work of Nepalese artisans.

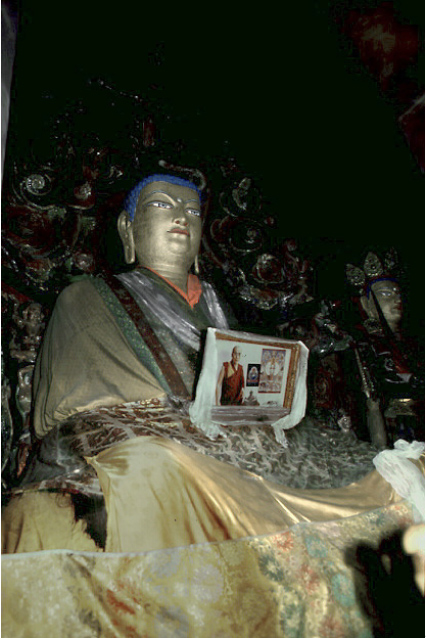

Although Lhasa lost its status as the capital after Zhang Rinpoche’s demise, it regained prominence with the establishment of the tradition by Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) and the founding of the three major monasteries Ganden, Sera, and Drepung, all of which supported the Jokhang. The next phase of renovation in the Jokhang was led by the Fifth Dalai Lama (1617–1682) (fig. 10), whose government attracted many cosmopolitan visitors and instituted major annual ritual celebrations in Lhasa. The wealth of the Geluk government during the Fifth Dalai Lama’s reign and the great influx of pilgrims to the Jokhang brought donations of sculptures as well as renovations, notably the refurbishment of the Jowo’s throne by artisans. The following Dalai Lamas and the great lay-ruler Polhane (1689–1747) all made donations of special sculptures and maintained the Jokhang throughout the period of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Wall painting of Gushri Khan and the Fifth Dalai Lama’s regent; Lhasa, U region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China); photograph by Karl Debreczeny

The early twentieth century witnessed the arrival of the British Younghusband expedition in 1904 and Chinese armed forces led by Zhao Erfeng (1845–1911). During the battles, artillery damaged the Jokhang’s gilded copper roofs, but with the expulsion of the troops, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama (1876–1933) rapidly restored the temple to its former splendor as pilgrims once more thronged the site. The Reting Regent and the Fourteenth (b. 1935) likewise contributed to the glory of the Jokhang. Subsequently, the upper apartments were renovated and a new gilded copper roof fabricated. The (1966–1977) brought much destruction, notably due to extensive fires. Sweeping renovations were made before Tibet opened to foreign tourists in about 1980, bringing the monument to world attention. In 2000 the Jokhang was nominated to the UNESCO World Heritage List of Monuments as part of the Potala Palace. On February 17, 2018, as Lhasa started Losar celebrations, a giant fire that broke out in the upper story of the Jokhang imperiled the Jowo Shakyamuni (fig. 11). In spring 2018, the Jokhang reopened to pilgrims and devotees, and like a phoenix, the Jowo Rinpoche emerged in full glory, as if unscathed by the flames.

Jowo Shakyamuni; northern India or Tibet; 500 BCE? or 11th century CE; about life-size; Rasa Trulnang Tsuklakhang (Jokhang Temple), Lhasa; photograph by Stefan Auth

Per K. Sørensen and Guntram Hazod, Thundering Falcon: An Inquiry into the History and Cult of Khra-’brug, Tibet’s First Buddhist Temple (Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2005), 17; Knud Larsen and Amund Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas: Traditional Tibetan Architecture and Townscape (Boston: Shambhala, 2001), 115.

Knud Larsen and Amund Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas: Traditional Tibetan Architecture and Townscape (Boston: Shambhala, 2001), 116.

Knud Larsen and Amund Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas: Traditional Tibetan Architecture and Townscape (Boston: Shambhala, 2001), 116–17.

Brandon Dotson translates the record of 641–642 CE in The Old Tibetan Annals, Brandon Dotson, The Old Tibetan Annals: An Annotated Translation of Tibet’s First History (Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2009), 82.

Erberto Lo Bue, “Newar Artistic Influence in Tibet and China between the 7th and the 15th Century,” Rivista degli Studi Orientali 84, no. supplemento 1 (2011): 27–28.

Brandon Dotson, The Old Tibetan Annals: An Annotated Translation of Tibet’s First History (Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2009), 82.

Brandon Dotson, The Old Tibetan Annals: An Annotated Translation of Tibet’s First History (Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2009), 94, and for the Table of royal events, 240.

André Alexander, “Empire Road: Design and Positioning of Cultural Monuments of the Early Tibetan Empire” (2008), Site 8 Khra ’brug.

Per K. Sørensen and Guntram Hazod, Thundering Falcon: An Inquiry into the History and Cult of Khra-’brug, Tibet’s First Buddhist Temple (Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2005), 17; Amy Heller, “The Ramoche Restoration Project, Lhasa,” Orientations 39, no. 6 (September) (2008): 85–87.

Michael Aris, Bhutan: The Early History of a Himalayan Kingdom (Warminster: Aris and Phillips, 1979), 12–31; Janet Gyatso, “Down with the Demoness: Reflections on a Feminine Ground in Tibet,” Tibet Journal 12, no. 4 (1987): 37 passim.

Hugh E. Richardson, A Corpus of Early Tibetan Inscriptions (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1985), 27 passim.

Georgios T. Halkias, “The Mirror and the Palimpsest: The Myth of Buddhist Kingship in Imperial Tibet,” in Locating Religions: Contact, Diversity, and Translocality, ed. Reinhold Glei and Nikolas Jaspert (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 131.

Jacques Bacot, F. W. Thomas, and Gustave Charles Toussant, Documents de Touen-Houang Relatifs à l’histoire Du Tibet (Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1940), 153.

Gyurme Dorje, “Introduction,” in Jokhang: Tibet’s Most Sacred Buddhist Temple, ed. Gyurme Dorje et al. (London: Hans-Jörg Mayer, 2010), 11.

Gyurme Dorje translating Shakabpa, “Shakabpa’s Inventory,” in Jokhang: Tibet’s Most Sacred Buddhist Temple, ed. Gyurme Dorje et al. (London: Hans-Jörg Mayer, 2010), 73.

Erberto Lo Bue, “Newar Artistic Influence in Tibet and China between the 7th and the 15th Century,” Rivista degli Studi Orientali 84, no. supplemento 1 (2011): 40 and n87.

Gyurme Dorje, “Introduction,” in Jokhang: Tibet’s Most Sacred Buddhist Temple, ed. Gyurme Dorje et al. (London: Hans-Jörg Mayer, 2010), 21–24.

Dorjé, Gyurme, Tashi Tsering, Heather Stoddard, and Andre Alexander. 2010. Jokhang: Tibet’s Most Sacred Buddhist Temple. London: Hans-Jörg Mayer.

von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2001b. “Nepal: Licchavi Period; Wood Carvings of the Jokhang of Lhasa.” In Buddhist Sculpture in Tibet, vol. 1, 1:407–31. Hong Kong: Visible Dharma Publications.

Amy Heller, “Jokhang Temple, Lhasa: Tibet’s Most Sacred Temple,” Project Himalayan Art, Rubin Museum of Art, 2023, https://rubinmuseum.org/projecthimalayanart/essays/jokhang-temple-lhasa/.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Cum nihil placeat pariatur deserunt eius ullam incidunt maxime sunt ipsam. Ipsa, provident, laudantium, rem assumenda laboriosam veniam autem voluptas sint officia distinctio enim aut explicabo fuga animi voluptatum earum recusandae excepturi atque dignissimos iste? Exercitationem, praesentium eum. Harum ut maiores expedita exercitationem perspiciatis soluta aperiam dolores natus unde, sequi vitae debitis ex aliquam quas eum reprehenderit esse. Cumque amet et earum necessitatibus, repellendus ullam ducimus corporis architecto culpa placeat eum odit cum iure illo vitae rerum! Ullam et suscipit culpa? Eos voluptatum laudantium iste vero impedit adipisci maxime magni natus voluptatibus.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.