Beri is a style of Tibetan painting based on Newar painting of the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal. With the destruction of many Indian monasteries in the thirteenth century, Nepal became an increasingly important source for Buddhist teachers and artisan.

In Buddhist context, donor is a person who contributes to or commissions a religious work of art. This act is intended to increase merit on behalf of the benefactor and is dedicated to the benefit of all. It is also usually done for a specific purpose, such as longevity, prosperity, or well-being; to advance religious practice; or to ensure a good rebirth of a deceased relative, teacher, or friend. A similar practice is also known in Hinduism and Bon.

In the Himalayan context, iconography refers to the forms found in religious images, especially the attributes of deities: body color, number of arms and legs, hand gestures, poses, implements, and retinue. Often these attributes are specified in ritual texts (sadhanas), which artists are expected to follow faithfully.

Manjushri is one of the most important bodhisattvas in Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Considered the embodiment of wisdom, Manjushri is often recognized by his attributes: a sword which cuts through ignorance and a book, the Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom) Sutra. Emanations of Manjushri can also be recognized by these same attributes. Another important Chinese iconographic tradition depicts a youthful Manjushri riding on a lion. This form is associated with Manjushri’s abode on earth, Mount Wutai in China, one of the few Buddhist sites in China visited by Tibetan and Mongol pilgrims among others from all over Asia. Manjushri was seen as the protector deity of China, and the Manchu emperors of the Qing Dynasty who claimed to be emanations of Manjushri emphasized/promoted this association.

Sakya is the name of a monastery and of a major tradition of Tibetan Buddhism that originated there during the Later Diffusion of Buddhism. Sakya Monastery was the seat of power during Sakya-Mongol rule in Tibet (1260–1350s), founded on the priest-patron relationship. Notable Sakya figures include Sakya Pandita (1182–1251), who played an instrumental role in establishing Tibetan relations with the Mongols; Drogon Chogyel Pakpa (1234-1280), who served as Qubilai Khan’s imperial preceptor and invented the Pakpa Script; and Buton (1290–1364), who compiled the Tibetan Canon. The Sakya are particularly known for their Lamdre teachings. In the 1350s, Pakmodru replaced the Sakya political prominence.

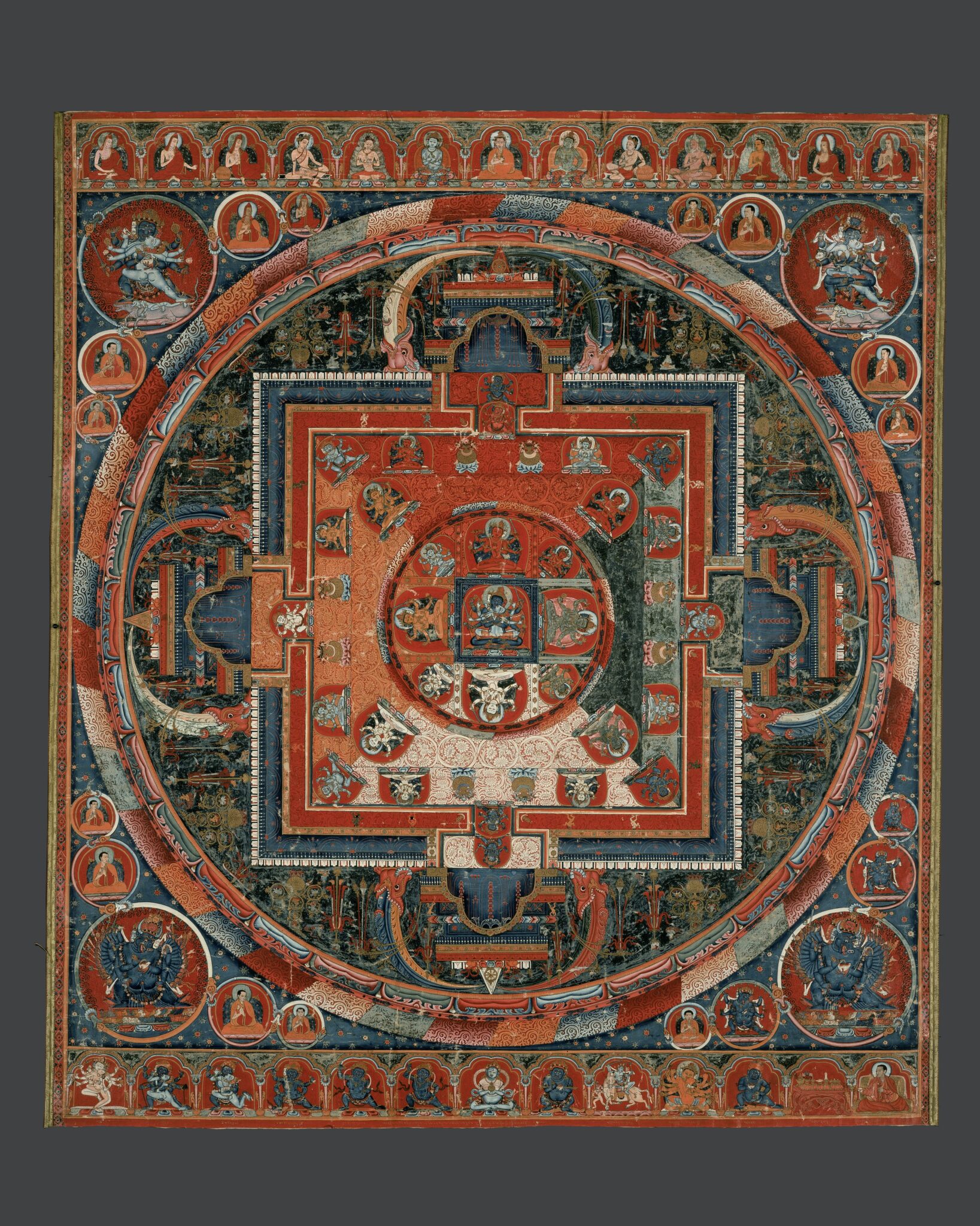

The Vajravali is a collection of esoteric teachings on mandala construction written by the Indian monk Abhayakaragupta (eleventh to twelfth centuries). The Vajravali was the first attempt to systematize and provide iconographic guides for the mandalas used in various Vajrayana tantras, which were widely transmitted in Tibet.