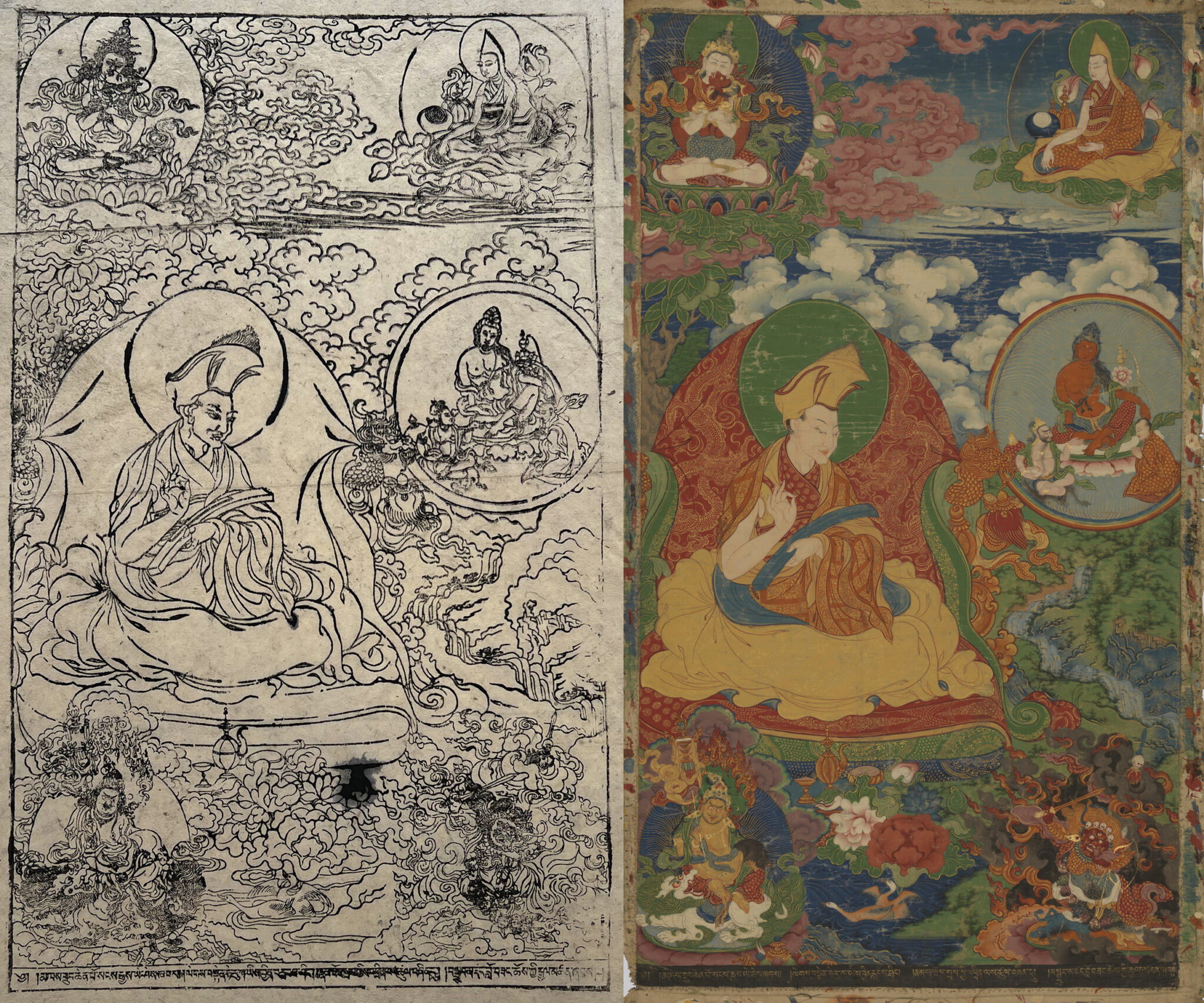

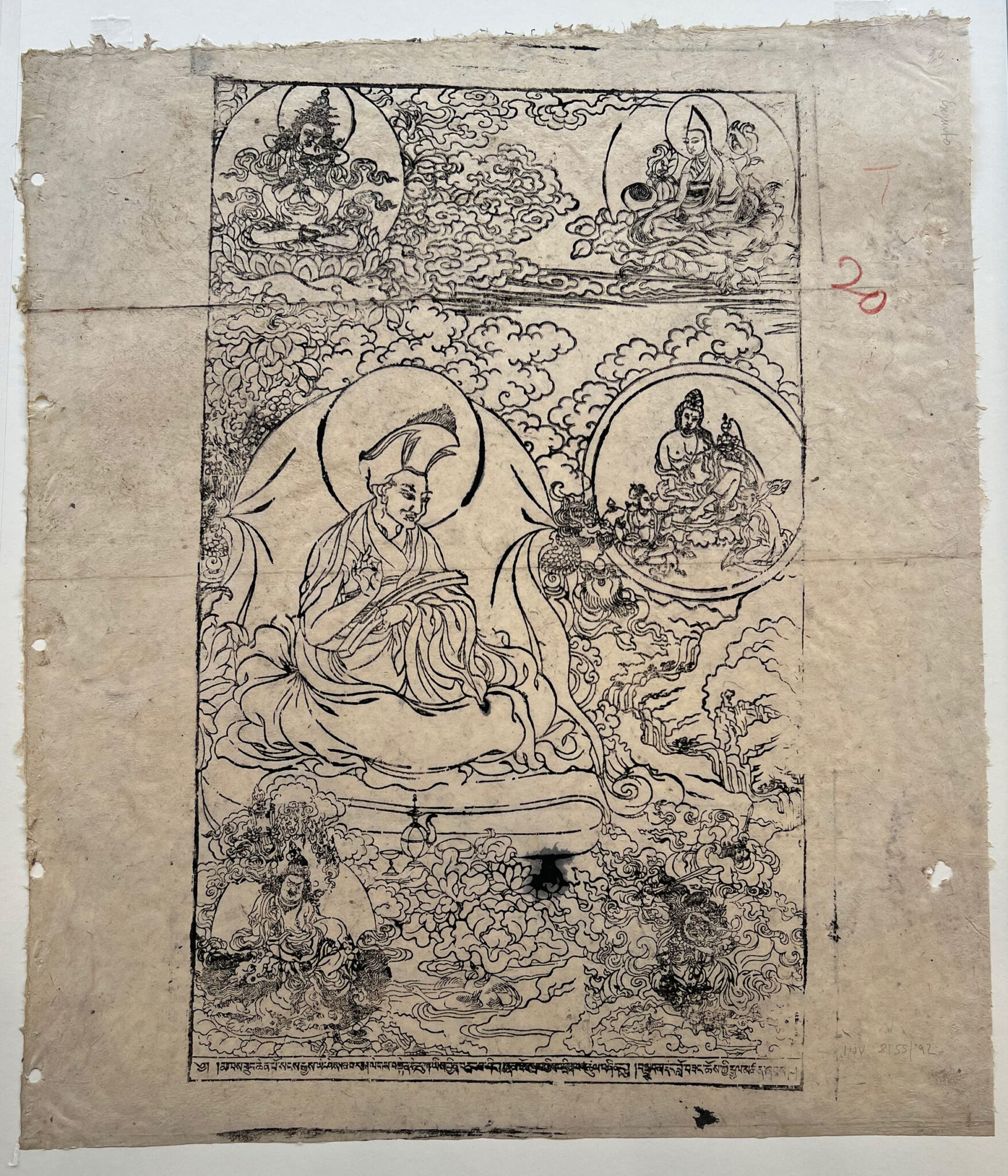

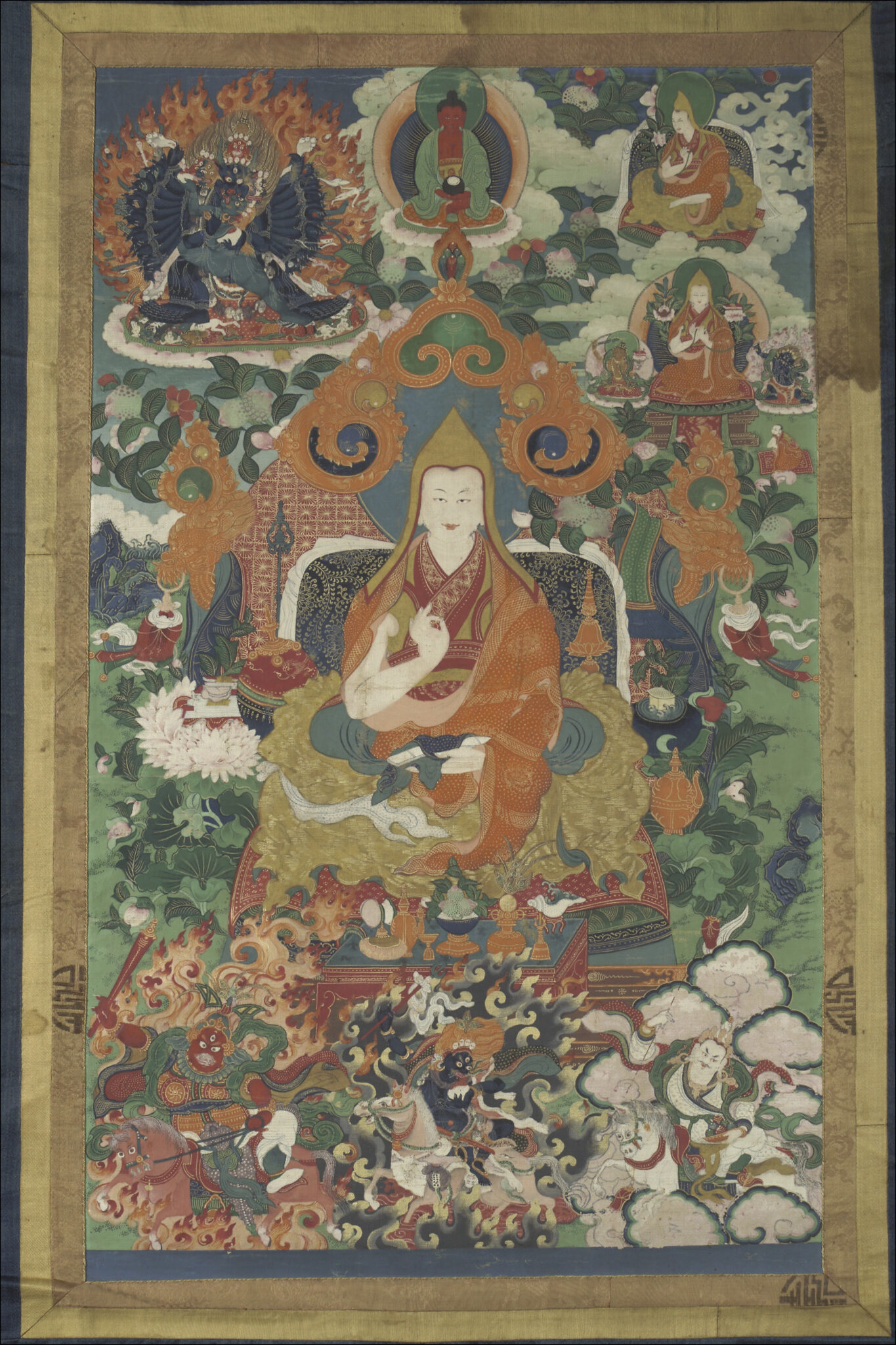

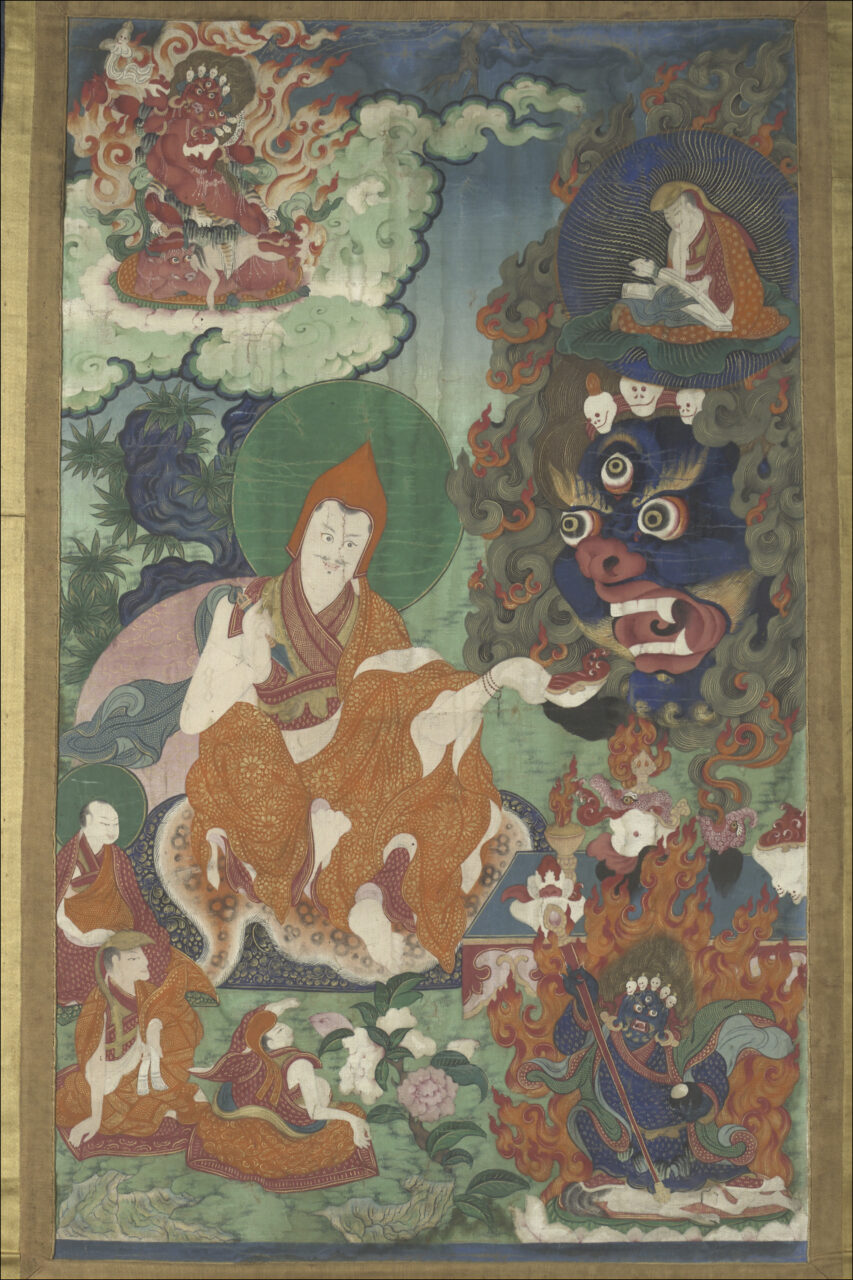

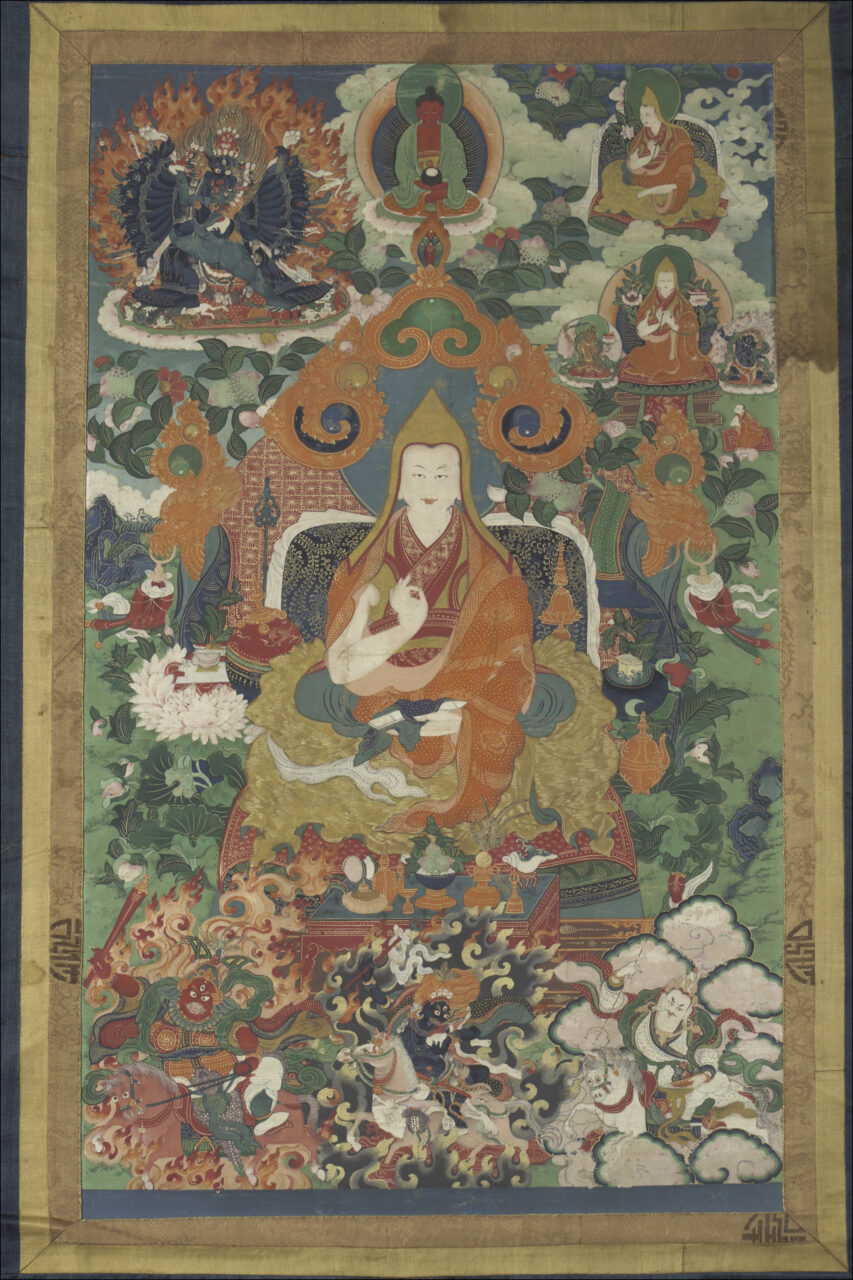

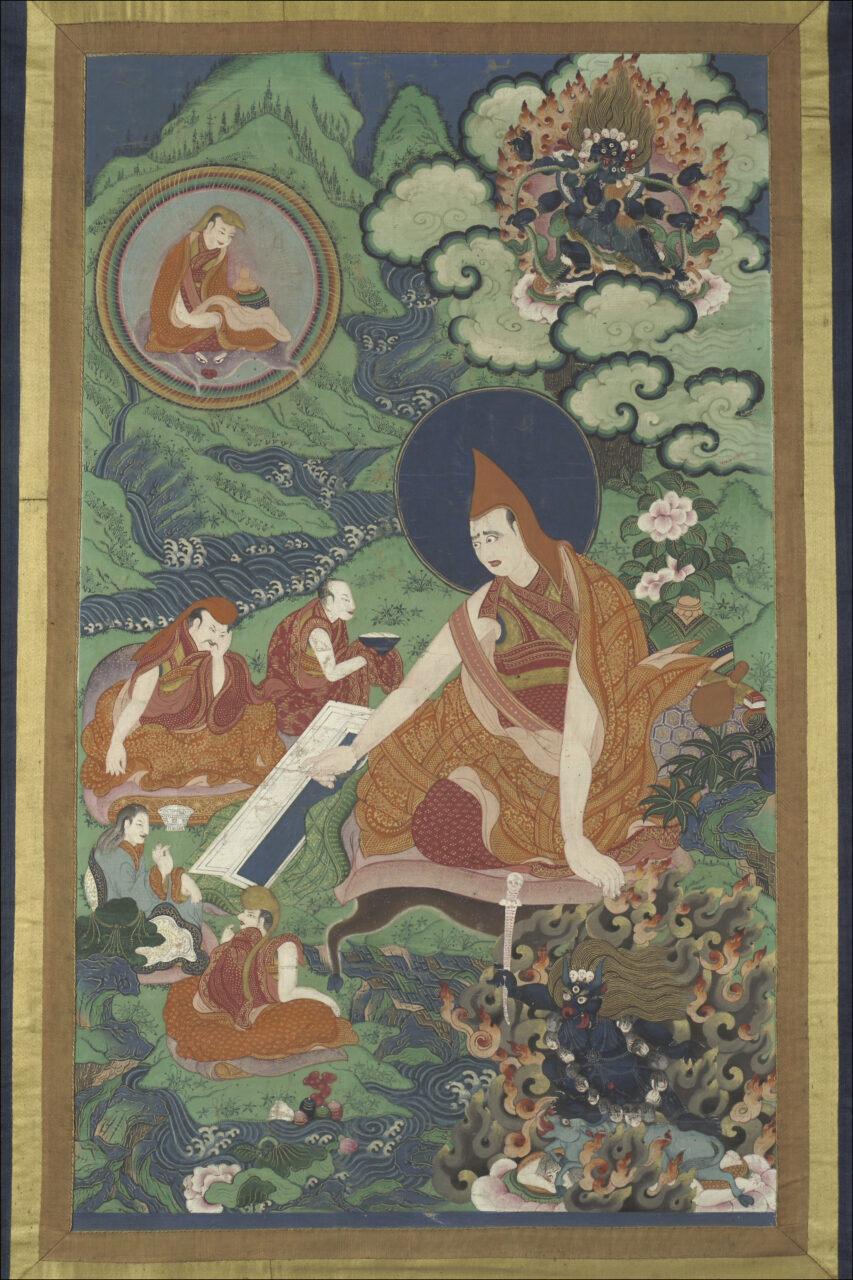

The Dalai Lamas are a tulku lineage that has played a central role in Tibetan history for the last five hundred years. In 1577 a Mongol khan gave the Geluk monk Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588) the title “Dalai Lama,” combining the Mongolian word for ocean, dalai (a reference to the depth of his knowledge), and the Tibetan word for guru, lama. Later, two previous incarnations were retroactively identified. The fifth incarnation, Ngawang Gyatso (1617–1682), allied with another Mongol khan to unite most of the Tibetan Plateau, forming the Ganden Podrang government that would govern Tibet until 1959. Since the Communist takeover, the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama has lived in exile at Dharamshala in India. The Dalai Lamas are understood to be emanations of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

Engraving is the process of incising lines, patterns, or writing into the surface of an object, such as a metal or wooden sculpture, or natural surface, such a stone.

The Geluk are the most recent of the major “Later Diffusion” traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. Founded on the teachings of Tsongkhapa (1357–1419 CE) and his students, the Geluk are known for their emphasis on monastic discipline and the scholastic study of Mahayana philosophy, especially Madhyamaka. In the seventeenth century the Geluk supporting the Dalai Lamas became the largest and most powerful Buddhist tradition in both Tibet and Mongolia, where city-sized Geluk monasteries and their satellites proliferated widely. For long periods, Geluk monks effectively ruled both countries in dual-rulership or priest-patron political systems. A follower of the Geluk is called a Gelukpa.

Hindus and Buddhist believe that all beings die and are reborn in new bodies, or “incarnations.” While reincarnation is recognized across the Buddhist world, in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, some important teachers (lamas) are thought to be able to control this process. Their successive incarnations, known as tulkus (emanation bodies), formed incarnation lineages such as Dalai Lamas, Panchen Lamas, Karmapas, and others.

A thangka is a Tibetan hanging scroll, usually painted on cotton, and then mounted in a silk brocade mount. Thangkas can also be textiles woven or assembled in the appliqué technique. Thangkas are often kept rolled up around a wooden dowel affixed to the bottom end of the silk mounting, which also helps keep the scroll flat when hung. Almost all thangkas show religious subjects. Similar paintings produced in Nepal are called “paubha.”

In Tibetan Buddhism, a tulku is a lineage of reincarnated lamas. Buddhists believe that sentient beings pass through infinite lives in samsara, reborn in new bodies after each death. Certain highly advanced practitioners are able to control this process, choosing their reincarnation. From the thirteenth century onward, this process became institutionalized in Tibet as a formal means of succession. When a tulku dies, a special team of monks and close disciples performs divinations and other tests to locate a child, who is then enthroned as the new incarnation of the lineage. Over the centuries, many of these lineages amassed immense estates (labrang), and became extremely powerful and prestigious within Tibetan and Mongol society. Important tulku lineages include the Karmapas, the Dalai Lamas, the Panchen Lamas, and the Jibzundambas.