The British Empire was the largest empire in world history, ruling almost a quarter of the world’s land area and population at its height in the mid-twentieth century. The British achieved hegemony in India after the Battle of Plassey in 1757, and soon came to rule large areas of the Himalayas, including Kashmir and Ladakh. Several small Himalayan kingdoms, including Nepal, Bhutan, and Sikkim, were allowed to maintain semi-independence as buffer-states against Qing-controlled Tibet. The British briefly invaded Tibet in 1903–1904. After the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1912, the British became a major cultural and military influence on the Ganden Podrang government in Lhasa. India achieved independence in 1947, ending British rule in the Himalayas.

The Dalai Lamas are a tulku lineage that has played a central role in Tibetan history for the last five hundred years. In 1577 a Mongol khan gave the Geluk monk Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588) the title “Dalai Lama,” combining the Mongolian word for ocean, dalai (a reference to the depth of his knowledge), and the Tibetan word for guru, lama. Later, two previous incarnations were retroactively identified. The fifth incarnation, Ngawang Gyatso (1617–1682), allied with another Mongol khan to unite most of the Tibetan Plateau, forming the Ganden Podrang government that would govern Tibet until 1959. Since the Communist takeover, the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama has lived in exile at Dharamshala in India. The Dalai Lamas are understood to be emanations of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

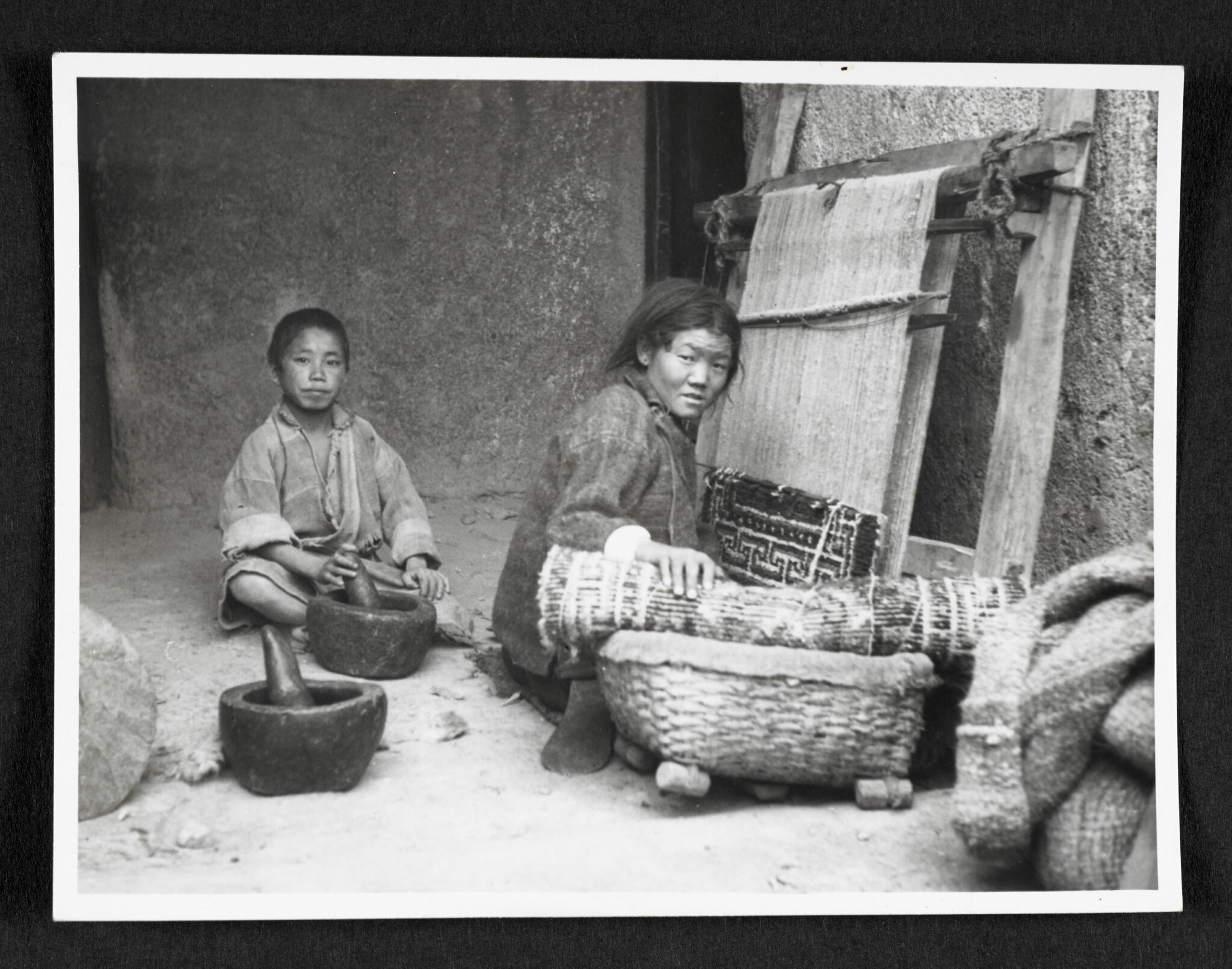

In weaving a pile is a portion of yarn that protrudes above the surface of the backing fabric, creating a soft and deep texture for a carpet or garment. A “knotted pile” carpet is one in which the pile is created by knotting yarn into the warp and weft to create loops of protruding fiber. Pile loops can sometimes be cut open to create an even more springy texture (a “cut-pile” carpet).