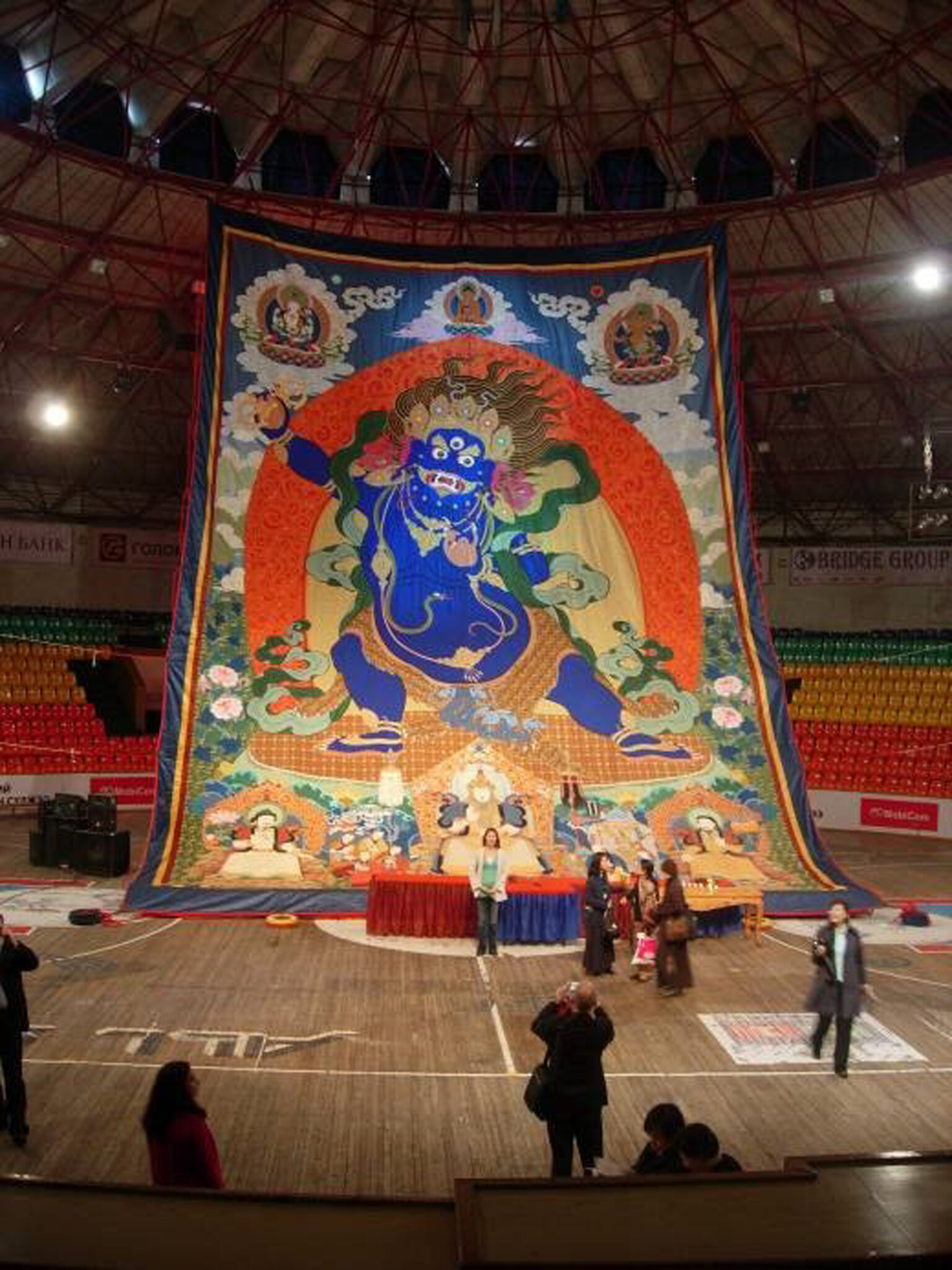

In Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, a dharmapala is a wrathful deity who is bound to protect the Buddhist teachings and its followers. Many dharmapalas were originally non-Buddhist deities, who were adopted into the Buddhist pantheon as fierce or wrathful protectors, for instance Bektse or Mahakala. There are many dramatic stories of forced conversion, or pacification of local gods by powerful masters, such as Padmasabhava who were assimilated to become protectors.

Gilding is a metalworking technique in which a fine golden surface is applied over a statue made of bronze. In Newar metalworking workshops, gilding is typically done with fire and mercury, which gives sculptures a warm finish (but is poisonous for their makers). In Tibetan contexts sometimes gold dust is mixed with glue and applied with a brush (often called “cold gold”), especially to a deity’s face to gain merit.

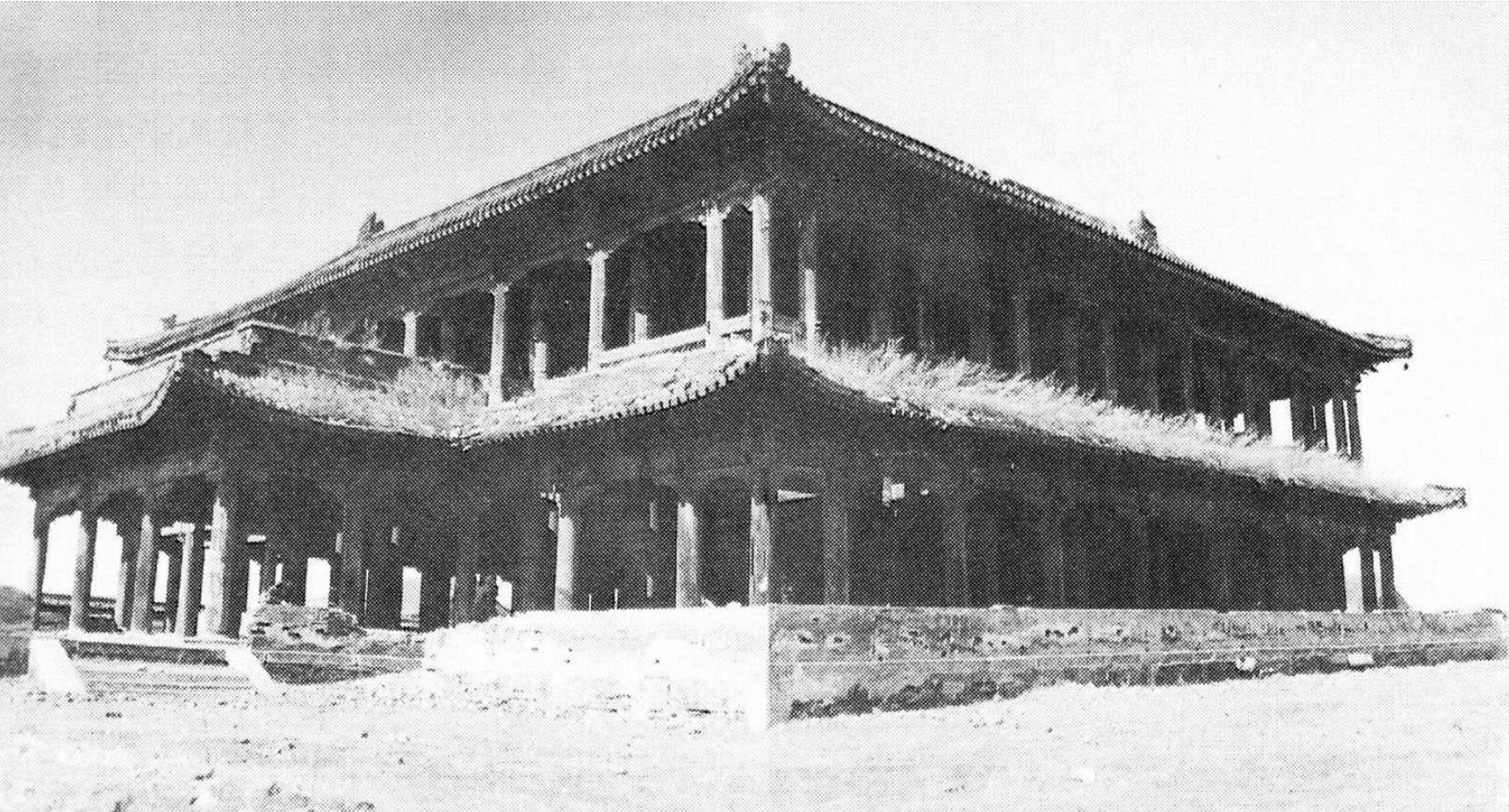

The Jibzundambas (from the Tibetan Jetsun dampa “venerable/reverend noble one”) were the most important lineage of tulkus in Khalkha Mongolia from 1639 to 1924, considered below only the Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas in prestige within the Geluk tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. While the Jibzundamba lineage traces its previous incarnations back to the Tibetan polymath and traveler Taranatha (1575–1634), the first formally enthroned Jibzundampa was the Mongolian prince and artist Zanabazar (1635–1723). As the Jibzundampa’s authority grew, their mobile monastery, called “the great encampment” (Mgl: yekhe khüriye), would gradually settle and develop into Mongolia’s modern capital, Ulaanbaatar. The eighth Jibzundamba ruled as khan of Mongolia from 1911 to 1924.

The Khalkha are one of the major historical subgroupings of the Mongols. Historically ruled by leaders descended from Chinggis Khan, the Khalkha inhabited a territory roughly the same as the country called Mongolia today. Other important Mongol groups after the fall of the Mongol Empire include the Chahars, who lived in what is today the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in China, the Oirat or Dzungars, who lived in Central Asia, and the Khoshut, who lived in the northern Tibetan Plateau.

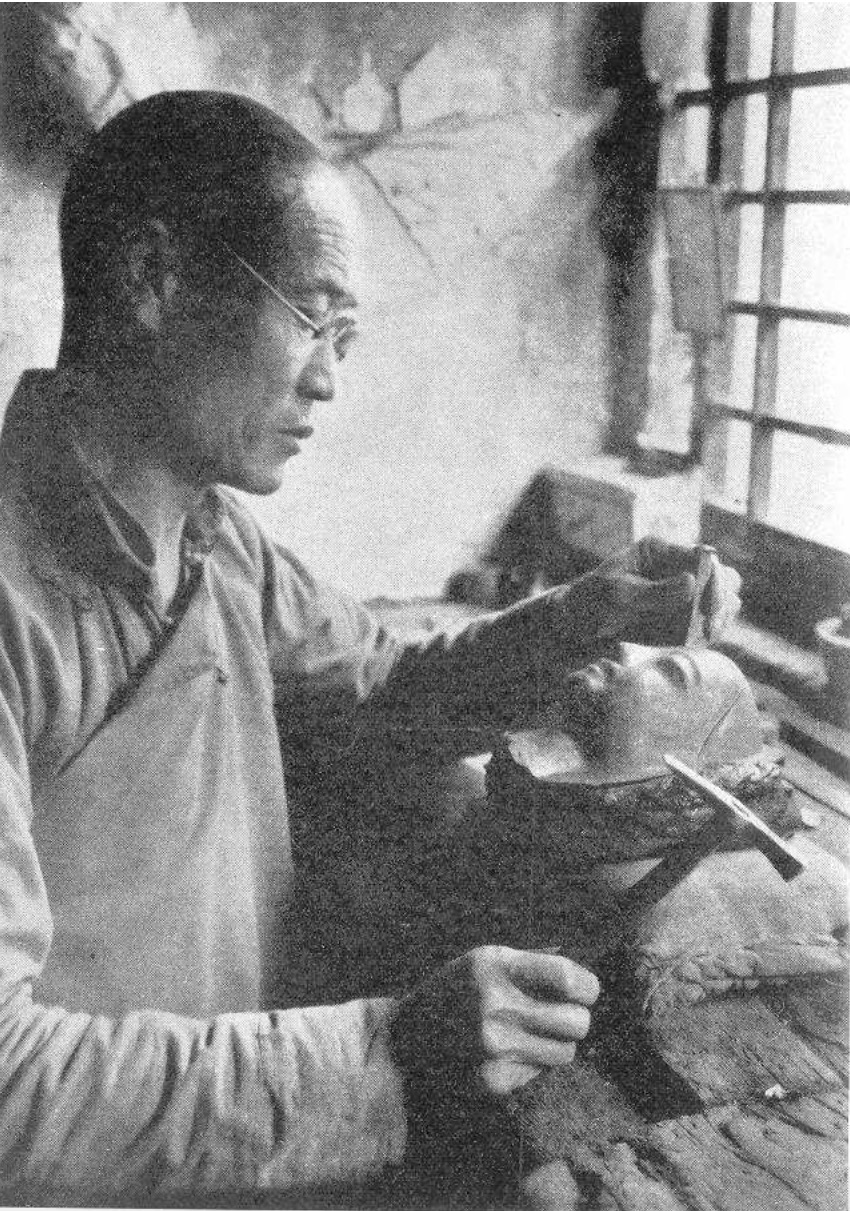

The lost-wax technique is a metal casting method used in many Asian cultures. First, the sculptor shapes an image out of beeswax. Then layers of clay are applied to the wax model, from fine to coarse, creating a mold, usually in several parts. When the clay mold is heated, the clay hardens and the wax is drained out. The metalworker then pours molten metal into the empty space of the mold through the same channels the wax was poured out. When the metal has cooled and hardened, the clay mold is broken off, revealing the rough metal statue inside. This statue is often then polished, chiseled, combined with parts that were cast separately, gilded, inlaid with precious substances, and painted.

Repoussé is a metal-working technique in which an artisan hammers the back side of a sheet of metal, indenting it outward to create an image in relief on the reverse face.