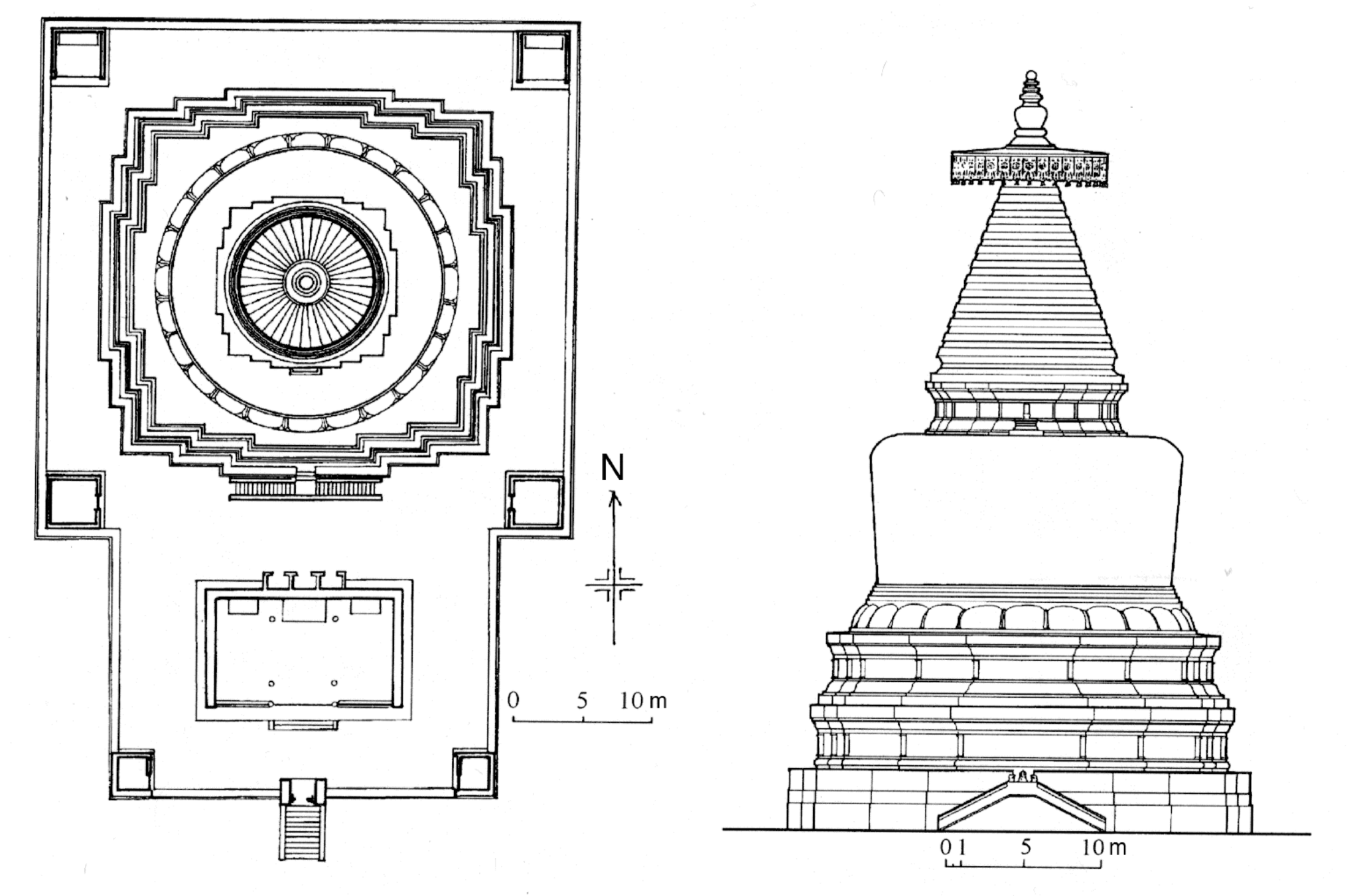

In Vajrayana Buddhism or Bon, a mandala refers to a cosmic abode of a deity, usually depicted as a diagram of a circle with an inscribed square that represents the deity enthroned in their palace, surrounded by members of their retinue. Mandalas can be painted, three-dimensional models, architectural structures, such as temples or stupas, or composed as arrangements of images within a temple. The instructions for creating and visualizing mandalas are usually found in ritual texts, such as tantras and sadhanas. Mandalas can be used in initiation ceremonies, visualized by a practitioner as part of deity yoga, consecrated and used to represent the divine presence within ritual space, offered to the deities as representations of the entire universe. A similar concept in Hinduism is a yantra.

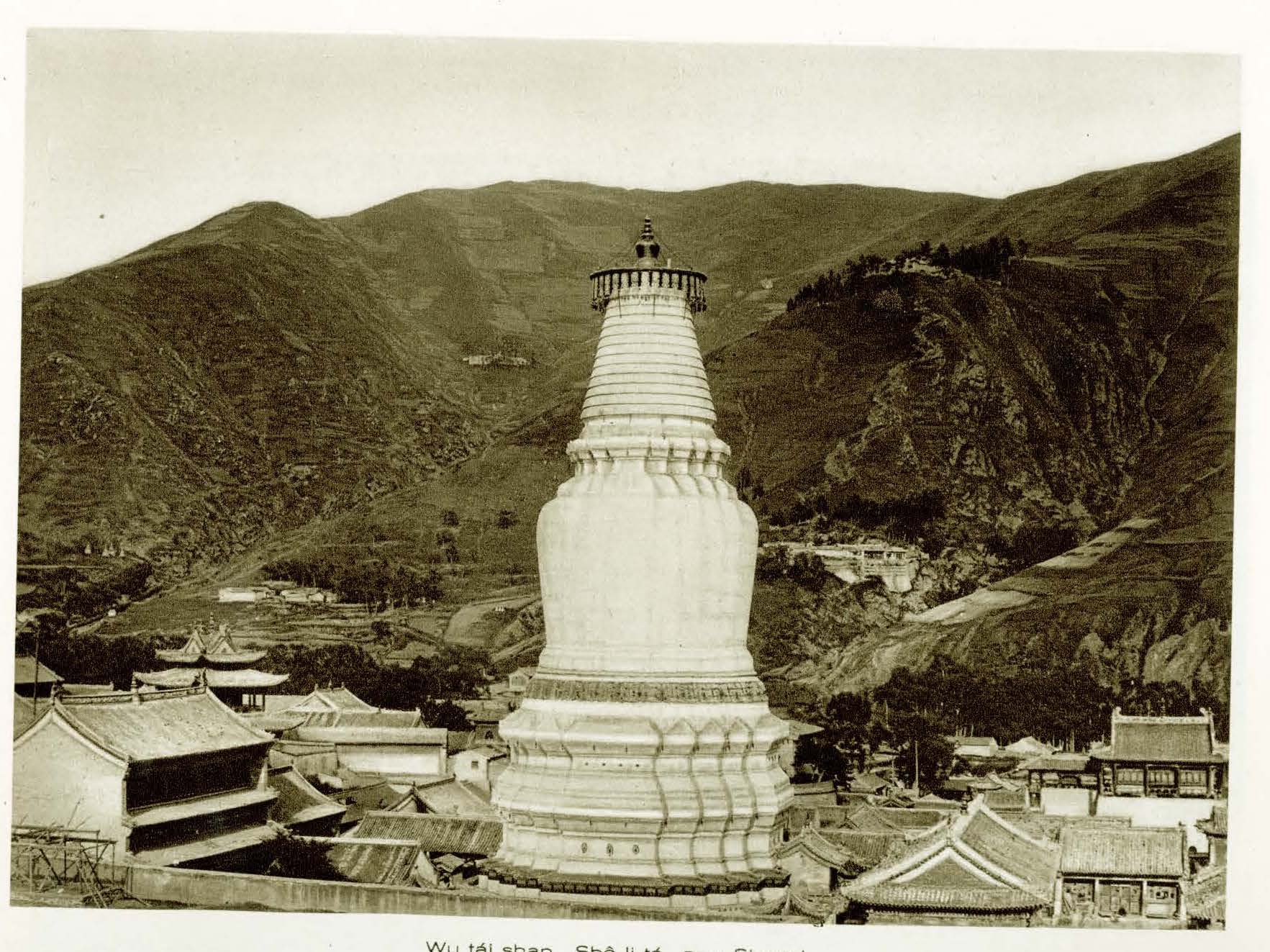

A monastery is a place where monks live, study, and perform ritual. It includes temples and other structures. Monasteries are central to Buddhism, and are also important in Bon, Hinduism, and Daoism. In Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian areas, some monasteries are enormous, wealthy, and powerful institutions, with branches of satellite monasteries forming networks across regions, often with thousands of monks, many decorated chapels, and huge holdings of land. Other monasteries, called hermitages, can be extremely simple, little more than a cave where hermits meditate. Generally, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery will have an assembly hall, several temples (Tib. lhakhang) for worship of specific deities, a protector chapel, as well as monks’ accommodations. A related institution in Newar Buddhism are the baha and bahi.

The Newars are traditional inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal. The Newars speak a Tibeto-Burman language (Newari) and practice both Hinduism and Buddhism. The Newars are inheritors of one of the oldest and most sophisticated urban civilizations of the Himalayas, and Newar arts and artisans have been celebrated all across the Himalayan world since the Licchavi period.

A practice of hiring and commissioning artists to create works of art. In religious context patrons were often rulers, religious leaders, as well as ordinary people. (see also donor)

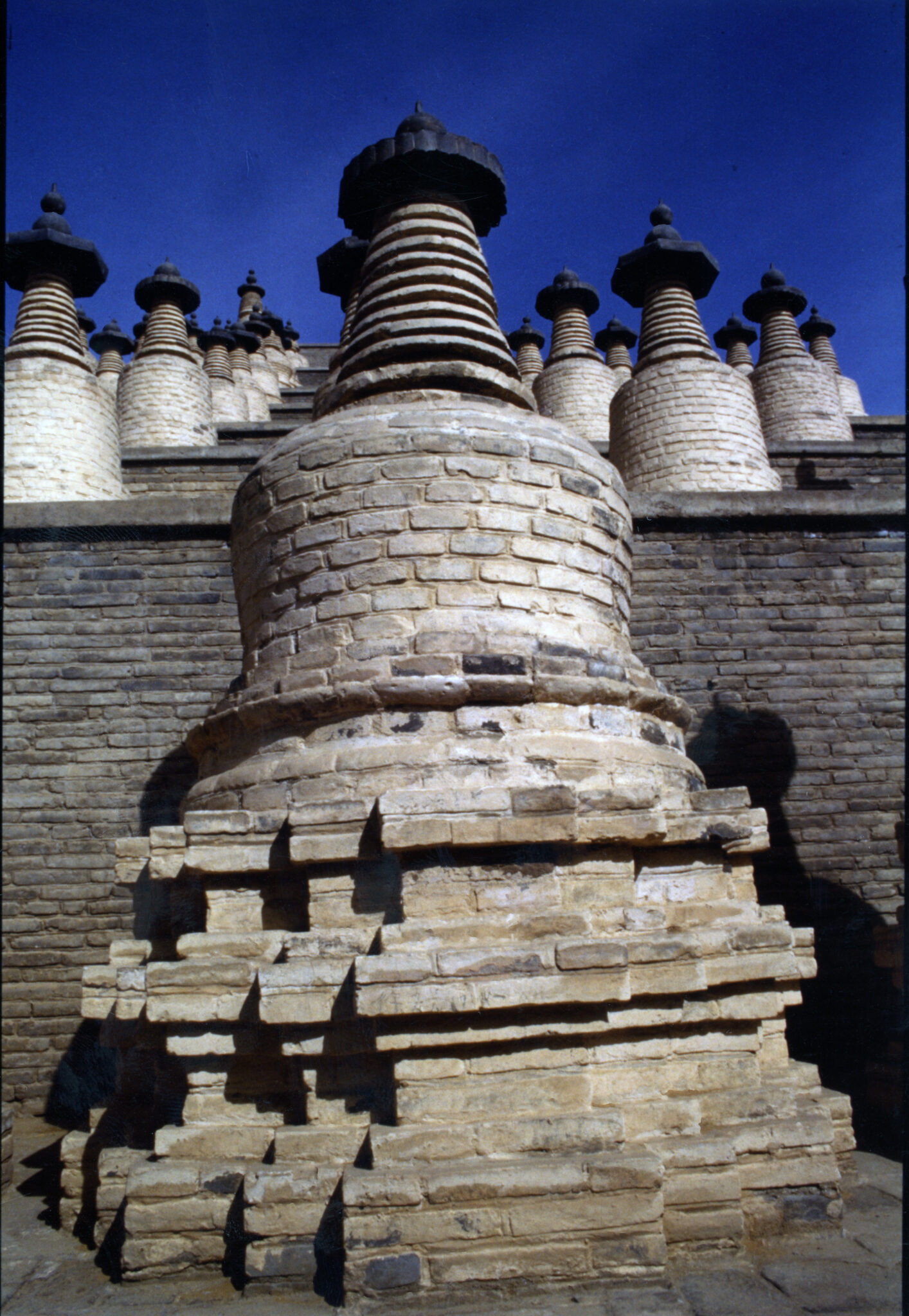

In the Buddhist context, a relic is an object or body part of a past master or sacred figure, including Buddha Shakyamuni himself (bones, ashes from cremation, even entire mummified bodies). Another important category of relics is called “sharira” in Sanskrit (Tib. ringsel)— small, pearl-like objects that are found within the cremated remains of enlightened teachers. Another category, known as contact relics, includes things owned or touched by religious masters, such as the Buddha’s robe or bowl. Important types widely used in Himalayan regions are dharma relics (dharma sharira), which are pressed clay plaques inscribed with the verse of dependent origination or mantras. Relics can be placed inside stupas, ground up and used for medicine, or kept in temples for the reverence of pilgrims. A container that holds relics is called a “reliquary.”

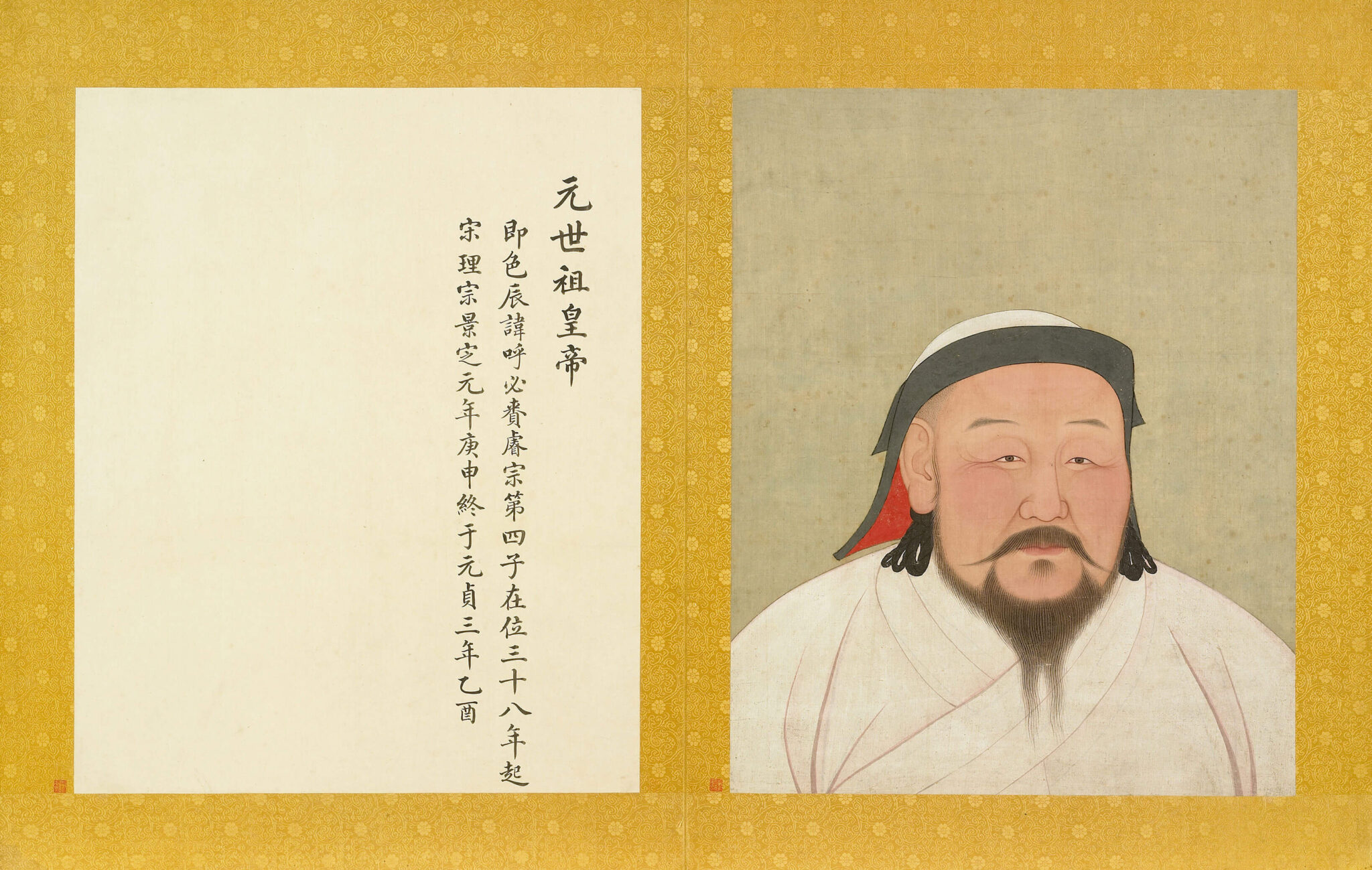

Historically, Tibetan Buddhism refers to those Buddhist traditions that use Tibetan as a ritual language. It is practiced in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, Ladakh, and among certain groups in Nepal, China, and Russia and has an international following. Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in two waves, first when rulers of the Tibetan Empire (seventh to ninth centuries CE), embraced the Buddhist faith as their state religion, and during the second diffusion (late tenth through thirteenth centuries), when monks and translators brought in Buddhist culture from India, Nepal, and Central Asia. As a result, the entire Buddhist canon was translated into Tibetan, and monasteries grew to become centers of intellectual, cultural, and political power. From the end of the twelfth century, Tibetans were exporting their own Buddhist traditions abroad. Tibetan Buddhism integrates Mahayana teachings with the esoteric practices of Vajrayana, and includes those developed in Tibet, such as Dzogchen, as well as indigenous Tibetan religious practices focused on local gods. Historically major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism are Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Geluk.