Buddha Shakyamuni, or simply “The Buddha,” is an epithet for Siddhartha Gautama, the founder of the Buddhist religion. While the exact dates of Siddhartha’s life are debated, scholars generally place him in the sixth to fifth century BCE. According to early Buddhist narratives, Siddhartha was born a prince of the Shakya clan in what is now northern India and southern Nepal. Choosing to leave his palace and family for a life as a religious ascetic, Siddhartha achieved enlightenment while meditating under the Bodhi Tree. Siddhartha spent the rest of his life as a wandering teacher, gathering disciples to form the early Buddhist monastic community (sangha). Buddha Shakyamuni is revered all over the Buddhist world today.

Circumambulation means walking around something. Himalayan Buddhists often circumambulate as a form of veneration and generate/accrue merit by walking in a clockwise direction around stupas, monasteries, or sacred mountains. Bonpos do the same thing, except counter-clockwise.

The Jonang are a tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. Founded by Dolpopa Sherab Gyeltsen (1292–1361), it is sometimes considered an offshoot of the Sakya tradition. Best known for the great scholar Taranatha (1575–1634), the Jonang emphasize the teachings of the Kalacakra Tantra, and are known for a unique interpretation of the doctrine of emptiness, which holds that all human concepts are empty of inherent nature, but the true substance of the universe is pure, radiant Buddhahood. The Jonang were suppressed by the Fifth Dalai Lama in the mid-seventeenth century in central Tibet, but the tradition survives in the Dzamtang region of Amdo, Eastern Tibet. A follower of the Jonang is called a Jonangpa.

Mahayana is a Buddhist movement, which formed in India around the first century CE. Mahayana followers articulated their goal of achieving buddhahood, or awakening, as the means to help all living beings, which is known as bodhicitta. Mahayana sutras such as Prajnaparamita, Avatamsaka, The Lotus Sutra, and others represent this goal in their narratives and explain how to reach it in their philosophical propositions. These texts introduced the idea of infinite buddhas in infinite intersecting universes and powerful bodhisattvas with the ability to intercede in human affairs. Mahayana philosophy emphasizes the teachings on emptiness, according to the Madhyamaka school and the ethical practices in the context of the bodhicitta. In Himalayan Buddhist traditions, Mahayana is considered the foundation for Vajrayana practices. Along with Theravada and Vajrayana it comprises the Three Vehicles of Buddhist paths. Mahayana teachings are also practiced today in China, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan.

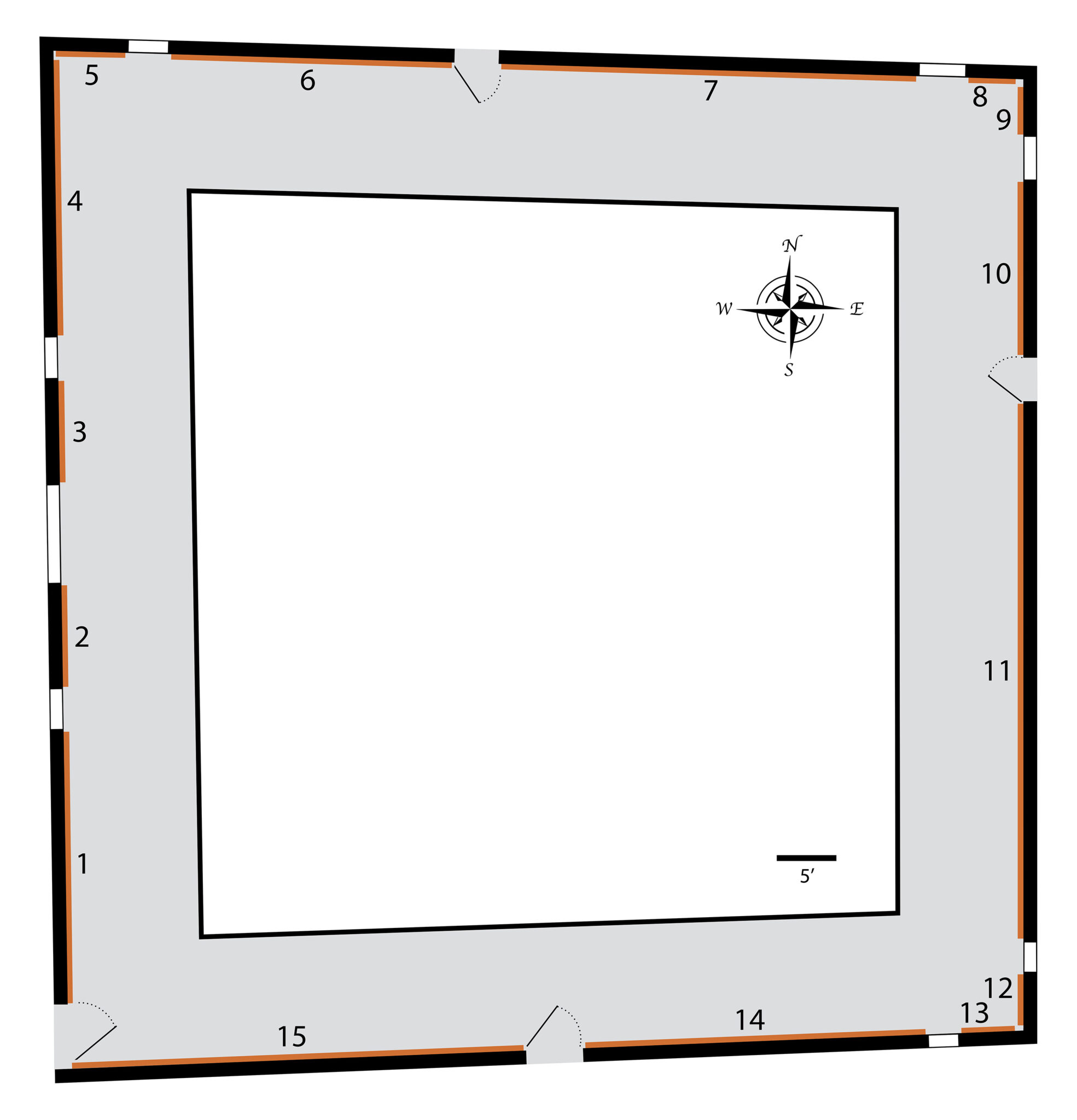

A monastery is a place where monks live, study, and perform ritual. It includes temples and other structures. Monasteries are central to Buddhism, and are also important in Bon, Hinduism, and Daoism. In Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian areas, some monasteries are enormous, wealthy, and powerful institutions, with branches of satellite monasteries forming networks across regions, often with thousands of monks, many decorated chapels, and huge holdings of land. Other monasteries, called hermitages, can be extremely simple, little more than a cave where hermits meditate. Generally, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery will have an assembly hall, several temples (Tib. lhakhang) for worship of specific deities, a protector chapel, as well as monks’ accommodations. A related institution in Newar Buddhism are the baha and bahi.