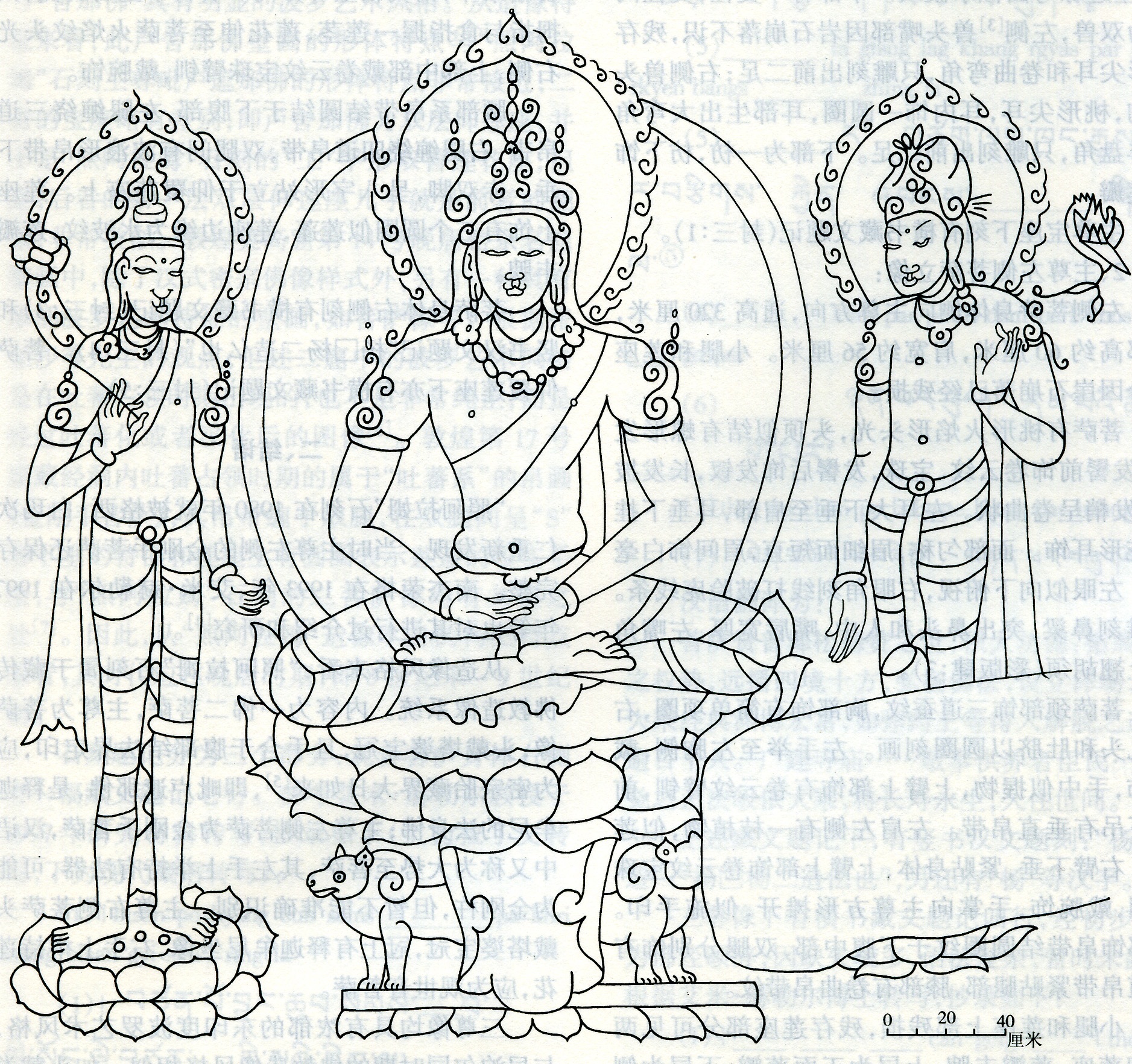

A chakravartin is an ideal of Buddhist kingship, a universal ruler who supports the sangha and “turns the wheel of the Dharma.” Since the time of Emperor Ashoka (304–232 BCE), the archetypal chakravartin, many Buddhist rulers in history have been praised as chakravartins, or rulers who support Buddhism and help its spread through the expansion of his domains.

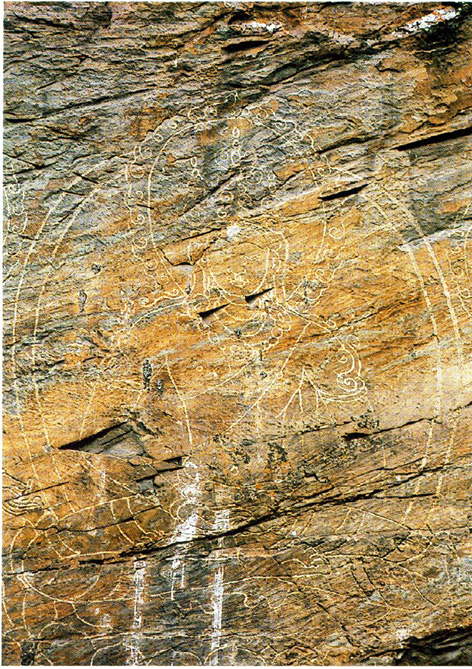

In the Himalayan context, iconography refers to the forms found in religious images, especially the attributes of deities: body color, number of arms and legs, hand gestures, poses, implements, and retinue. Often these attributes are specified in ritual texts (sadhanas), which artists are expected to follow faithfully.

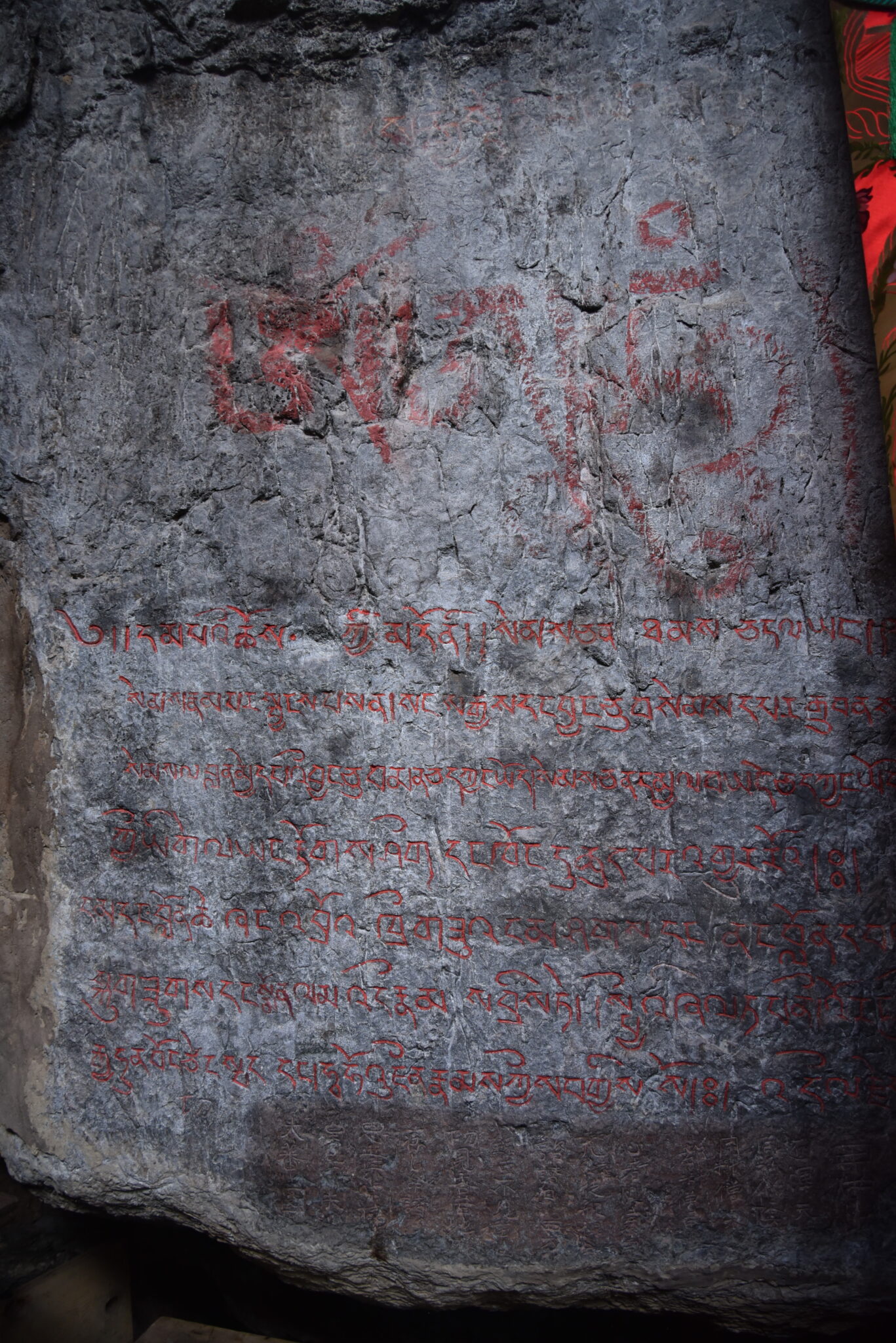

In the early seventh century, a line of kings from the Yarlung Valley united disparate people on the Tibetan Plateau into a powerful, centralized state. With their capital at Lhasa, these kings proclaimed themselves emperors, or tsenpo. Their armies conquered much of the Himalayas, Central Asia, and western China. Tibetans developed a written script for the Tibetan language and Buddhism was adopted as a state religion. The conversion to Buddhism was contested by an indigenous group of ritualists called Bon, creating political turmoil. After the assassination of emperor Langdarma in 842, the Tibetan empire fragmented and collapsed. Nevertheless, the myths and memories of the empire continue to be a central part of Tibetan identity.

Tsenpo is a title, sometimes conventionally translated as “emperor,” used for the rulers of the Tibetan Empire. Songtsen Gampo (d. 649 CE) was the first tsenpo, who unified most of the Tibetan Plateau and founded the Buddhist Jokhang Temple in Lhasa. The last tsenpo of the Tibetan empire was Langdarma (d. 842), an anti-Buddhist king whose assassination by a Buddhist monk sparked civil war, and ultimately the collapse of the Tibetan empire. Later Tibetan rulers who tried to declare themselves inheritors of the Tibetan empire, such as the rulers of the kingdom of Tsongkha in eastern Tibet (eleventh century), also employed this title to strengthen their claims.

Vairochana is an important buddha in Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. In Mahayana, Vairochana is considered the ultimate or Dharma-body of Buddha Shakyamuni. In the Charya and Yoga classes of the Four Classes of Tantra, Vairochana is the primordial Buddha or Adibuddha. In the Five Buddha Families, Vairochana is the head of the Buddha family, colored white, and usually located at the center. Across Asia, Vairochana as the Cosmic Ruler was also a powerful political symbol, and rulers associated themselves with Vairochana to enhance their claims as universal Buddhist sovereigns.