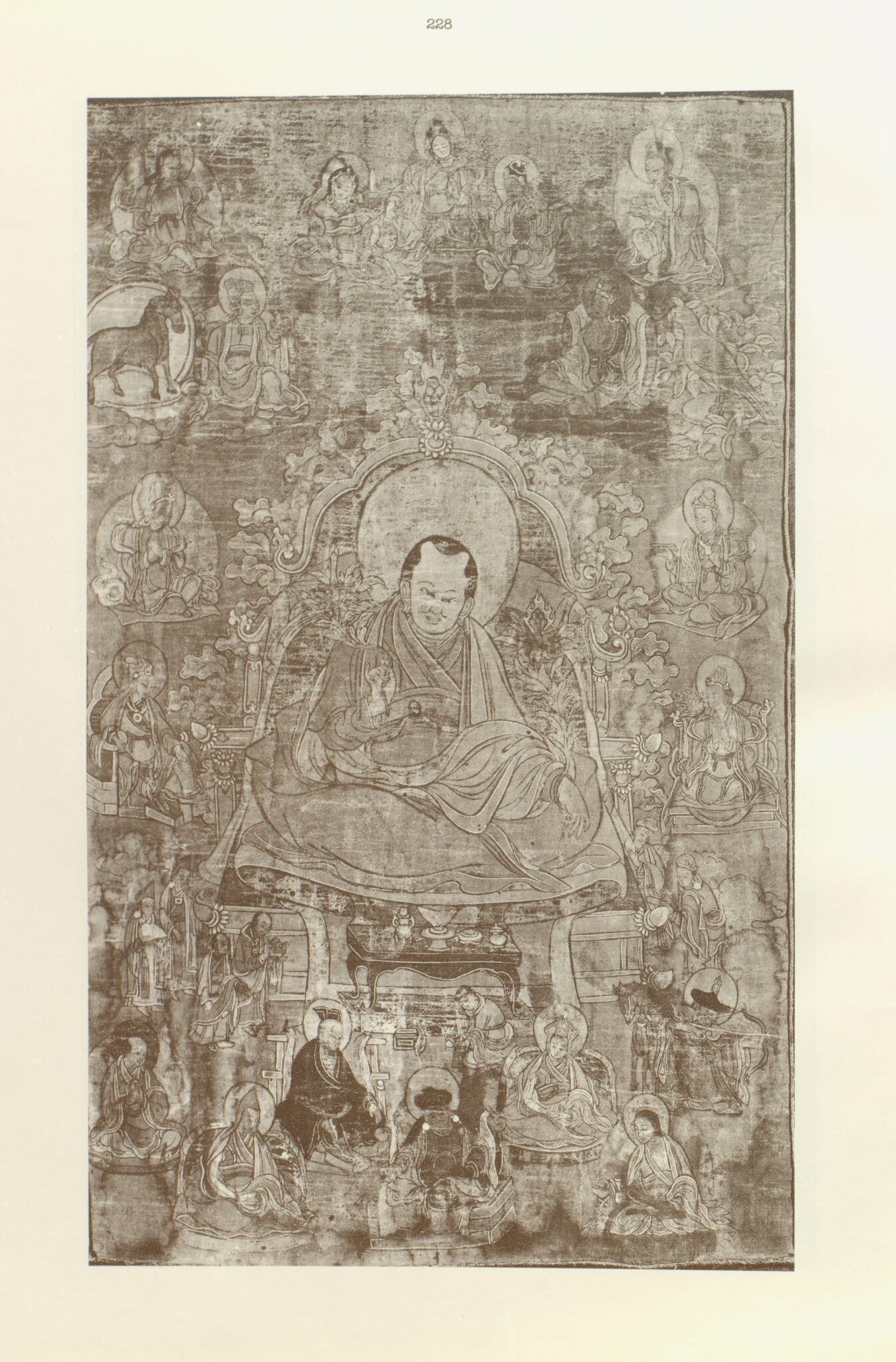

Avalokiteshvara, an embodiment of compassion, is a powerful bodhisattva, worshiped all across the Buddhist world. Avalokiteshvara is part of the very origin myth of the Tibetan people, and seen as the protector deity of Tibet. Many Tibetans believe that the emperor Songtsen Gampo, the Karmapas, and Dalai Lamas are all emanations of Avalokiteshvara. A special Avalokiteshvara image, the Pakpa Lokeshvara, is enshrined at the Potala Palace in Lhasa. In India and Tibet, Avalokiteshvara is understood as male, while in East Asian Buddhism, Avalokiteshvara is often thought of as female, and is known by the Chinese name Guanyin. Avalokiteshvara is recognizable in the Tibetan tradition by the lotus he holds, the image of Buddha Amitabha in his crown, and antelope skin over his shoulder.

The Dalai Lamas are a tulku lineage that has played a central role in Tibetan history for the last five hundred years. In 1577 a Mongol khan gave the Geluk monk Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588) the title “Dalai Lama,” combining the Mongolian word for ocean, dalai (a reference to the depth of his knowledge), and the Tibetan word for guru, lama. Later, two previous incarnations were retroactively identified. The fifth incarnation, Ngawang Gyatso (1617–1682), allied with another Mongol khan to unite most of the Tibetan Plateau, forming the Ganden Podrang government that would govern Tibet until 1959. Since the Communist takeover, the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama has lived in exile at Dharamshala in India. The Dalai Lamas are understood to be emanations of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

The Ganden Podrang was the government system that ruled Central Tibet, in one form or another, from 1642 to 1959. Headed by the Dalai Lamas, the Ganden Podrang had a dual system that included both powerful Geluk monastic officials and secular members of the Central Tibetan noble families. From the eighteenth century onward, the Ganden Podrang had a central governing council called the “kashag,” or “parliament.”

Hindus and Buddhist believe that all beings die and are reborn in new bodies, or “incarnations.” While reincarnation is recognized across the Buddhist world, in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, some important teachers (lamas) are thought to be able to control this process. Their successive incarnations, known as tulkus (emanation bodies), formed incarnation lineages such as Dalai Lamas, Panchen Lamas, Karmapas, and others.

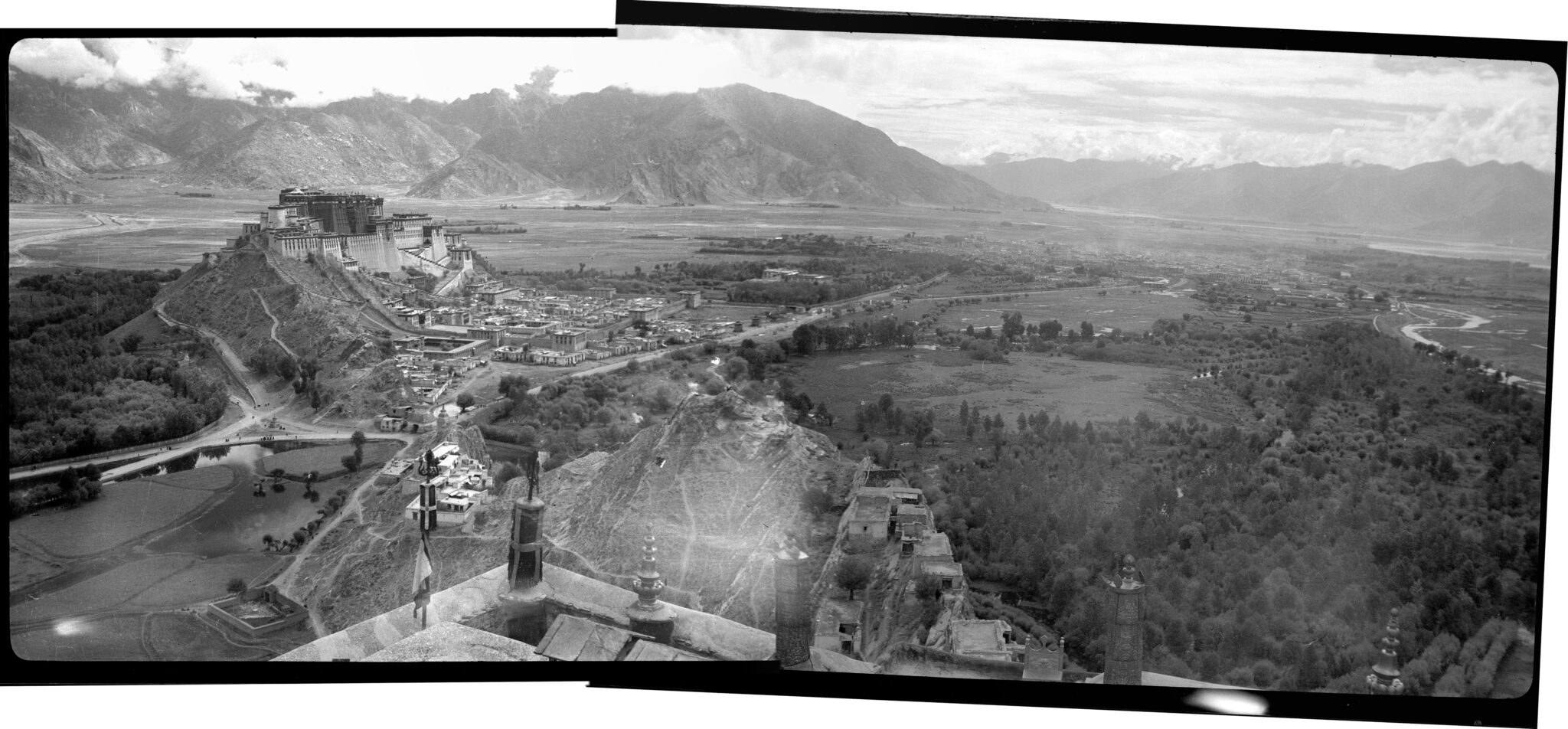

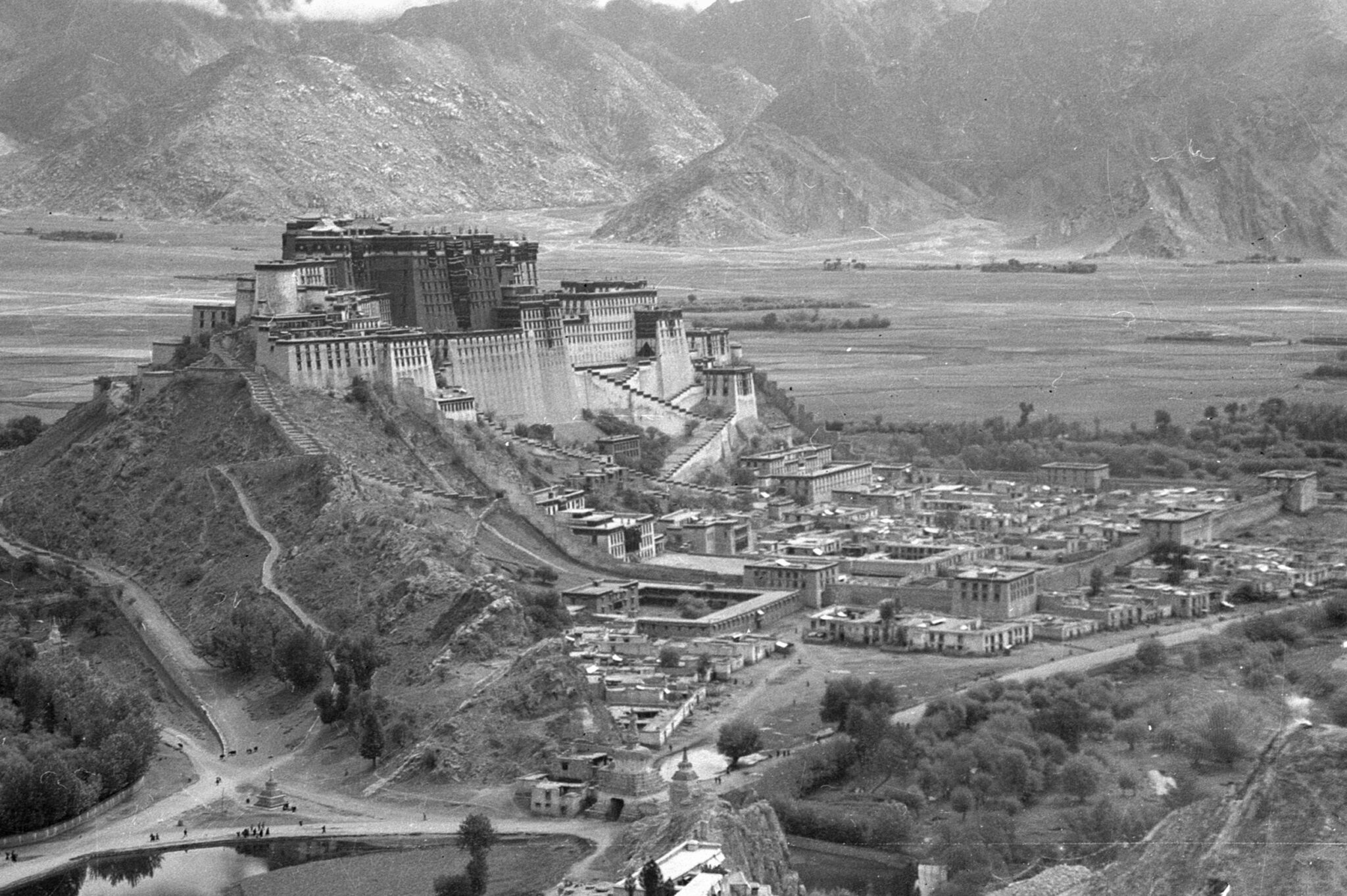

Mount Potalaka is a semi-mythical mountain in southern India, said to be the abode of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara on earth. Many sacred sites have been named after this mountain, including the Potala Palace of the Dalai Lamas (said to be emanations of Avalokiteshvara).

Historically, Tibetan Buddhism refers to those Buddhist traditions that use Tibetan as a ritual language. It is practiced in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, Ladakh, and among certain groups in Nepal, China, and Russia and has an international following. Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in two waves, first when rulers of the Tibetan Empire (seventh to ninth centuries CE), embraced the Buddhist faith as their state religion, and during the second diffusion (late tenth through thirteenth centuries), when monks and translators brought in Buddhist culture from India, Nepal, and Central Asia. As a result, the entire Buddhist canon was translated into Tibetan, and monasteries grew to become centers of intellectual, cultural, and political power. From the end of the twelfth century, Tibetans were exporting their own Buddhist traditions abroad. Tibetan Buddhism integrates Mahayana teachings with the esoteric practices of Vajrayana, and includes those developed in Tibet, such as Dzogchen, as well as indigenous Tibetan religious practices focused on local gods. Historically major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism are Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Geluk.