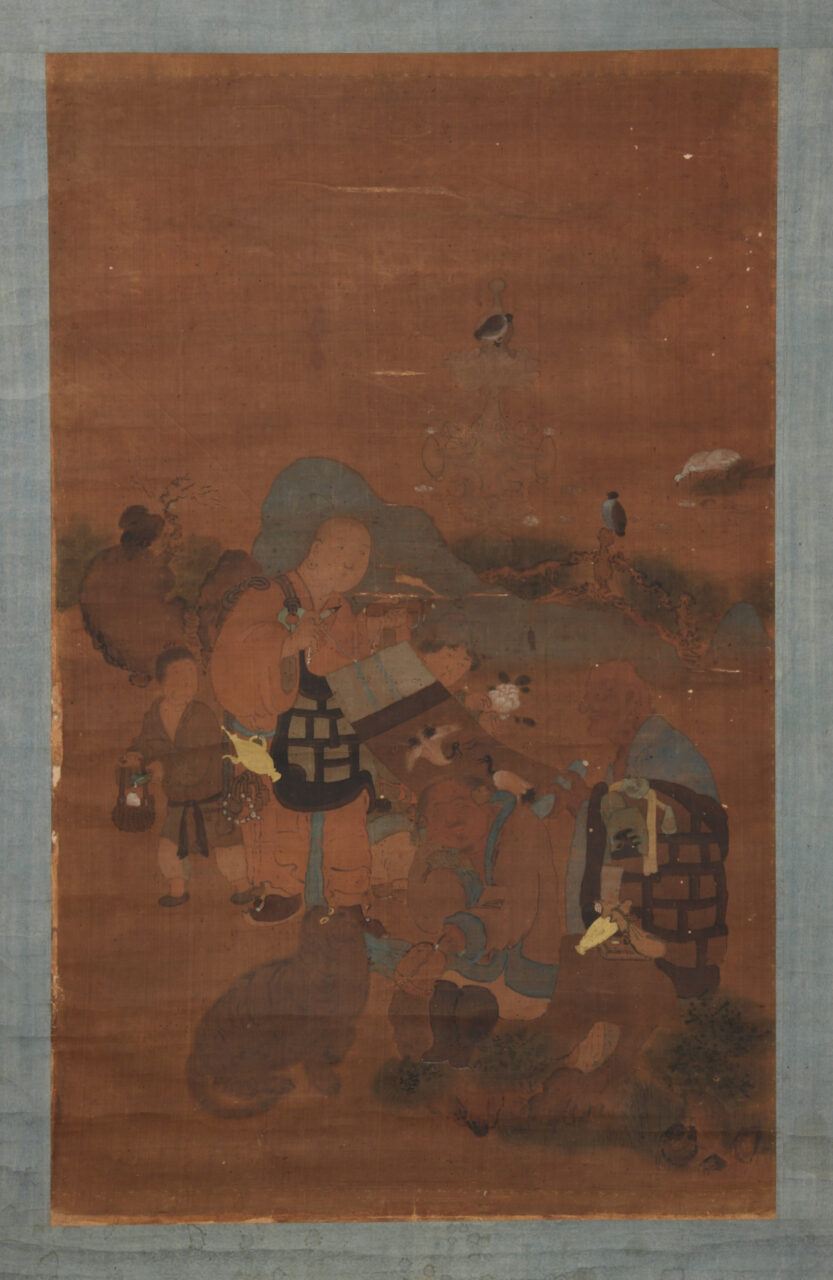

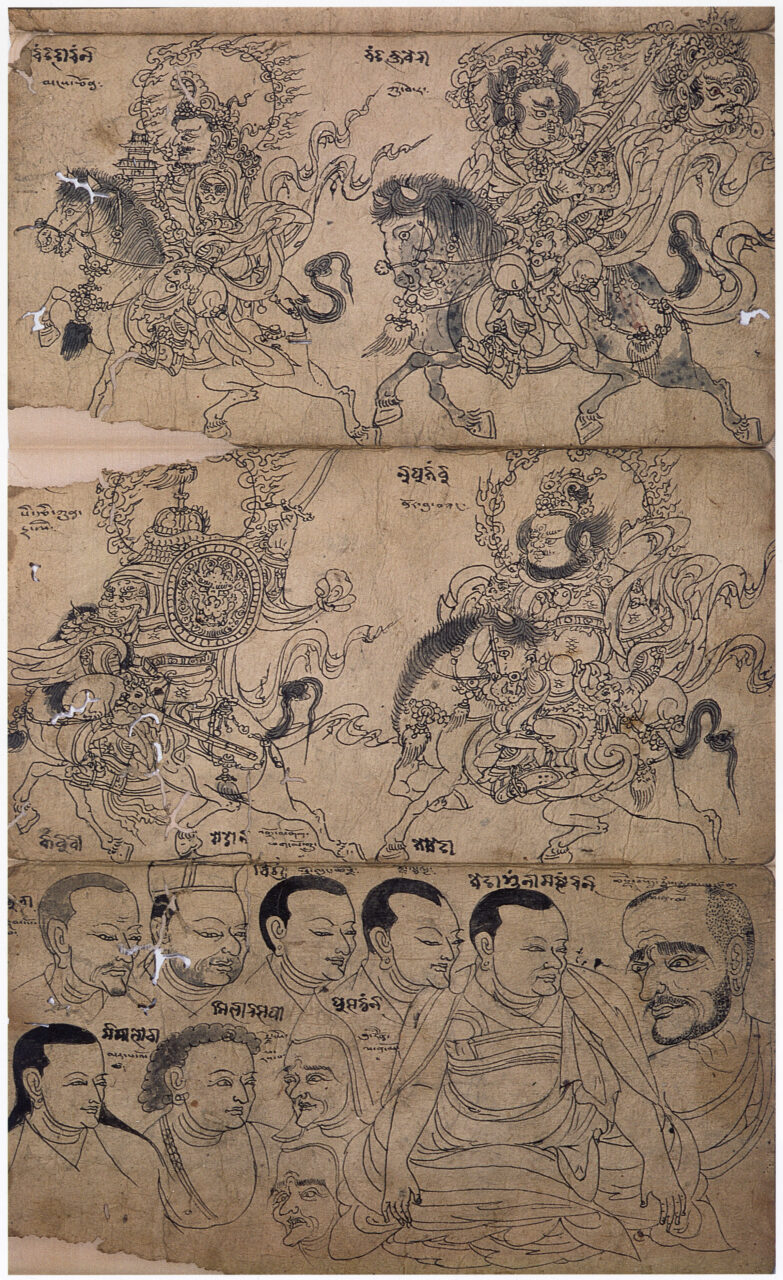

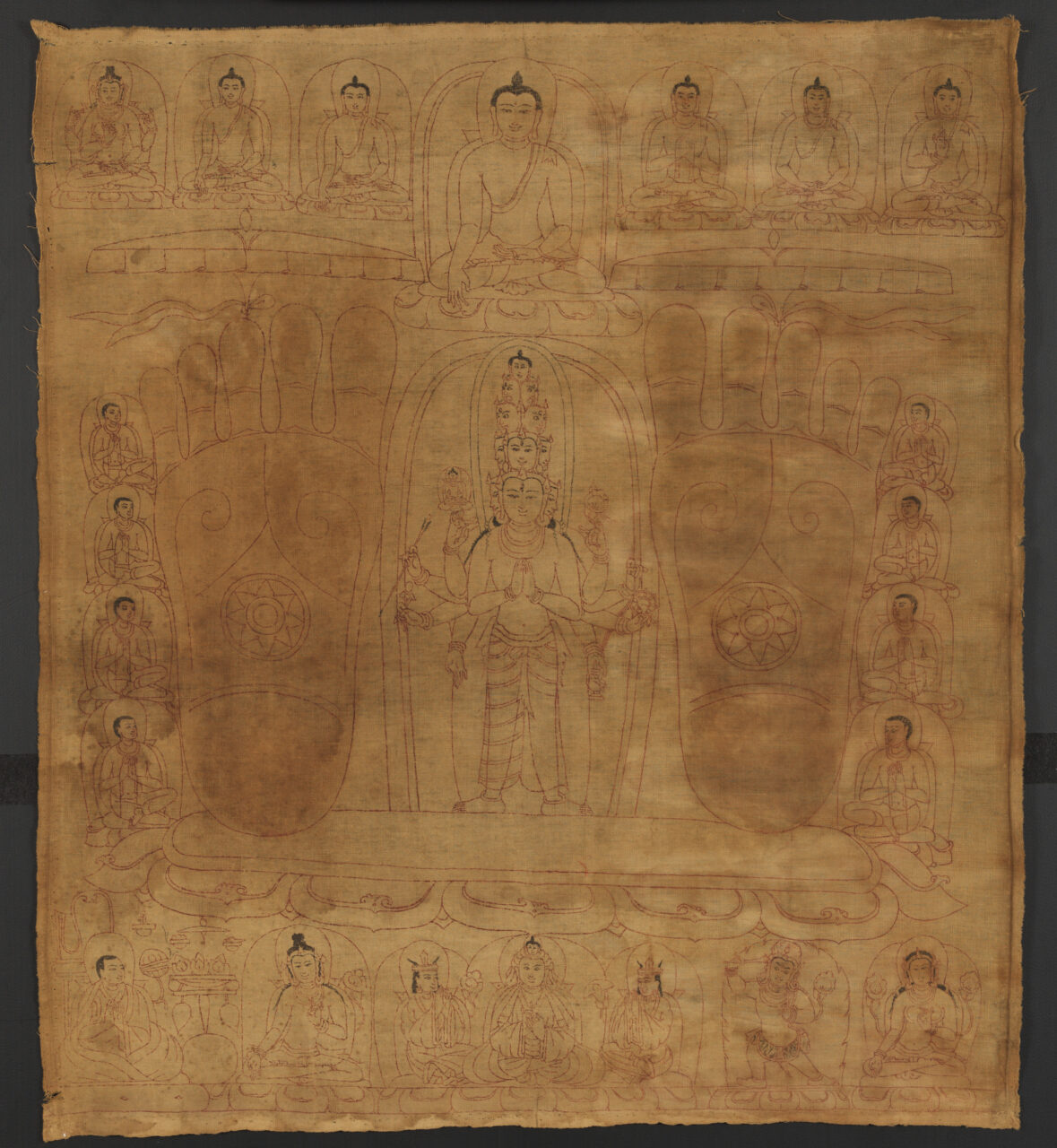

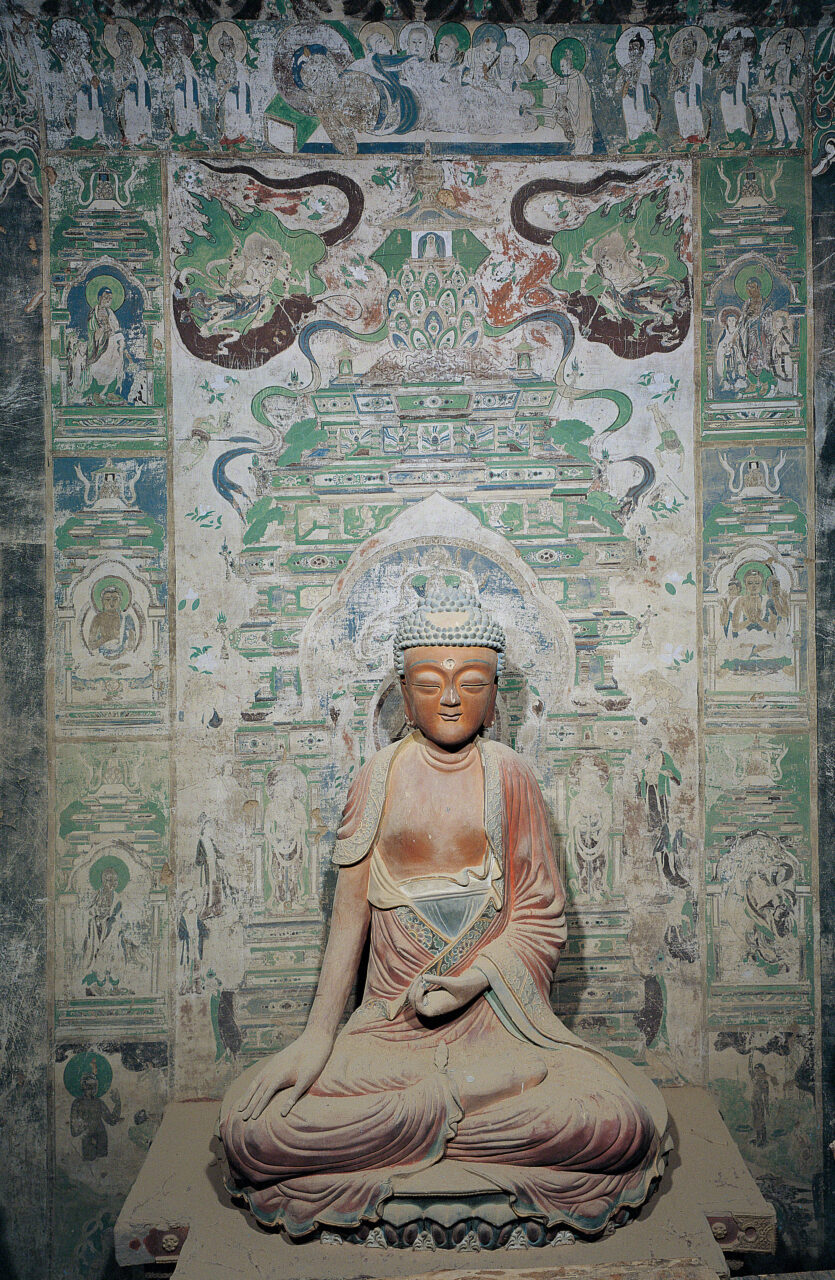

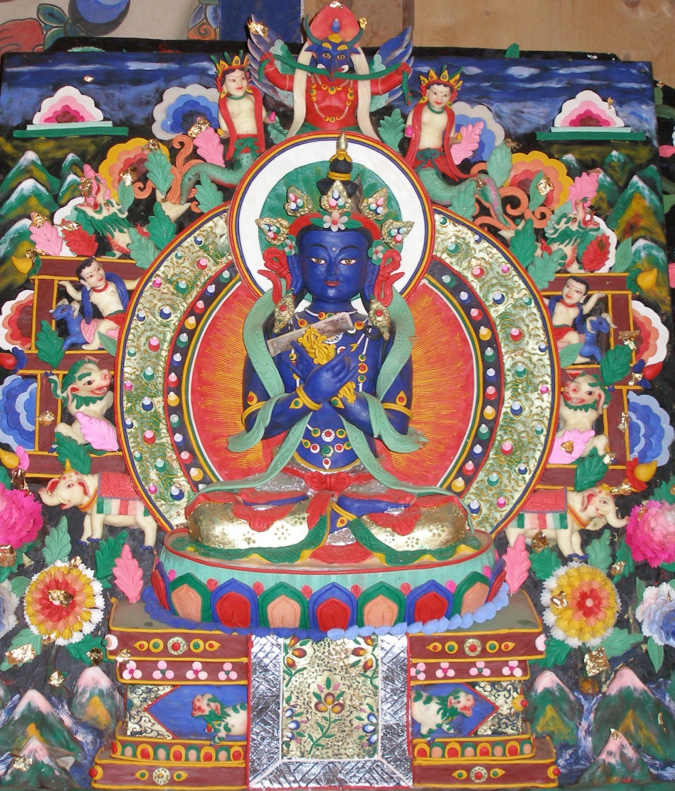

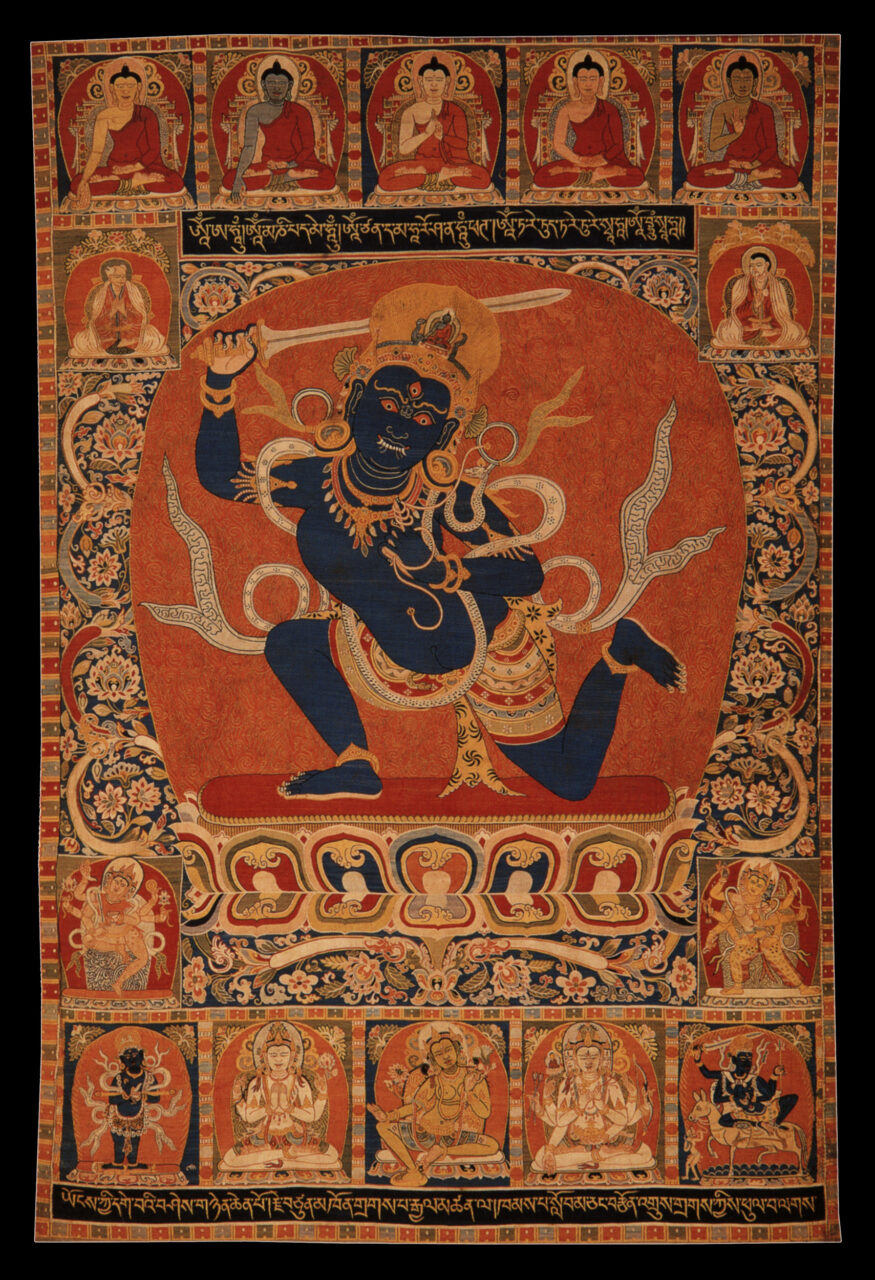

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a being who has made a vow to become a buddha or awakened. In the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, many bodhisattvas are understood as deities with enormous powers who delay their final enlightenment, remaining in the phenomenal world to help suffering beings. Among such great bodhisattvas are Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Maitreya.

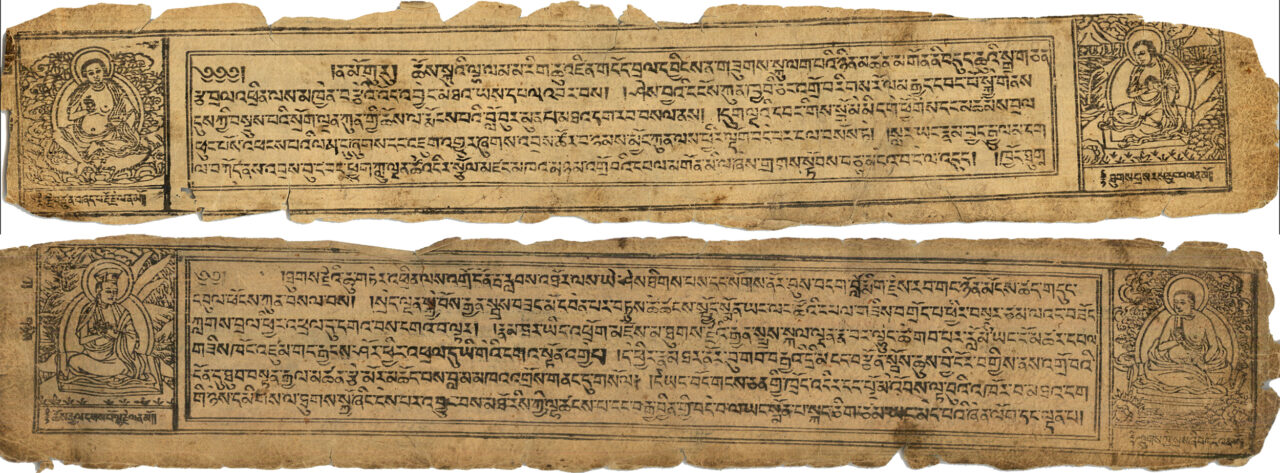

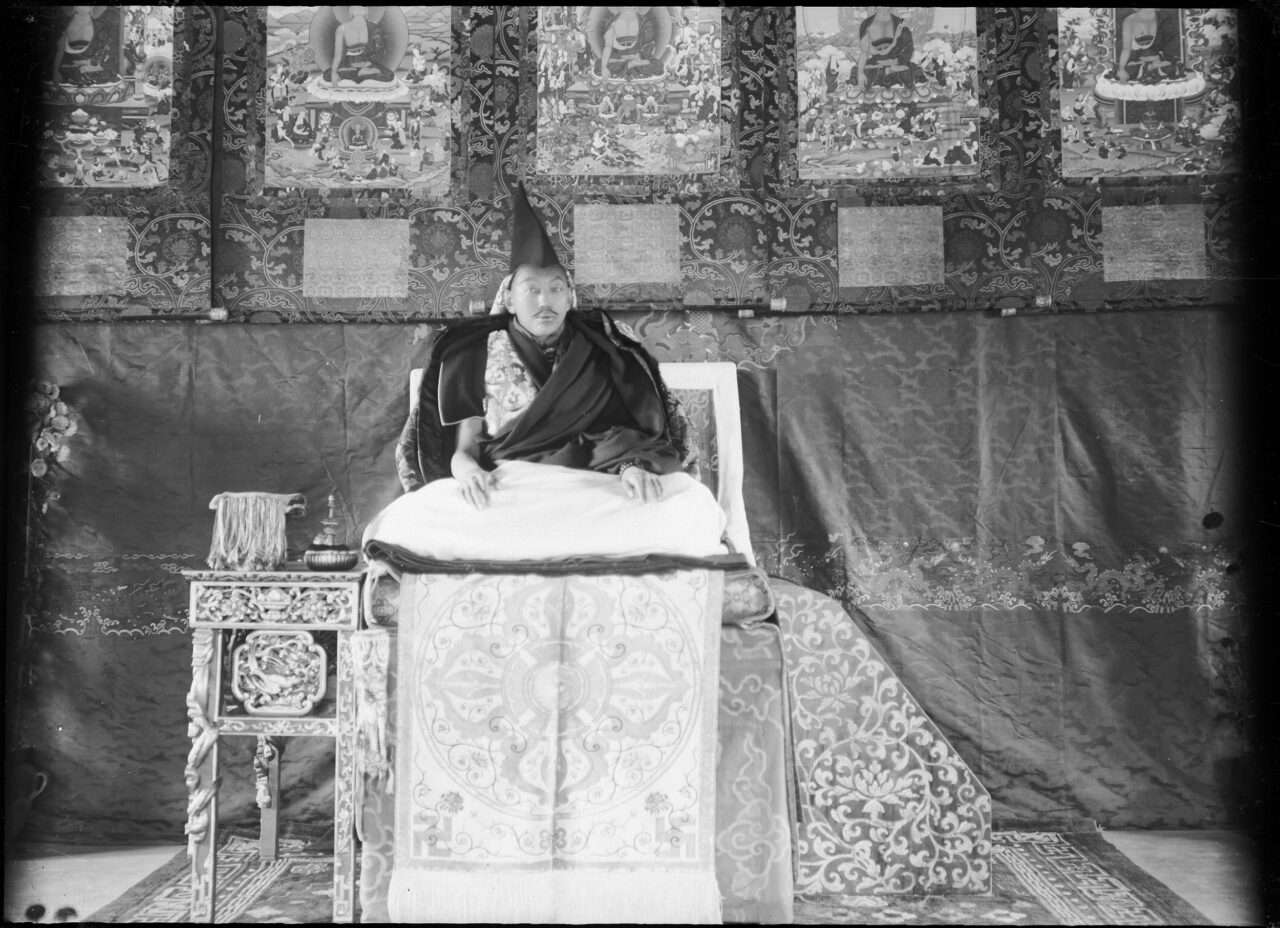

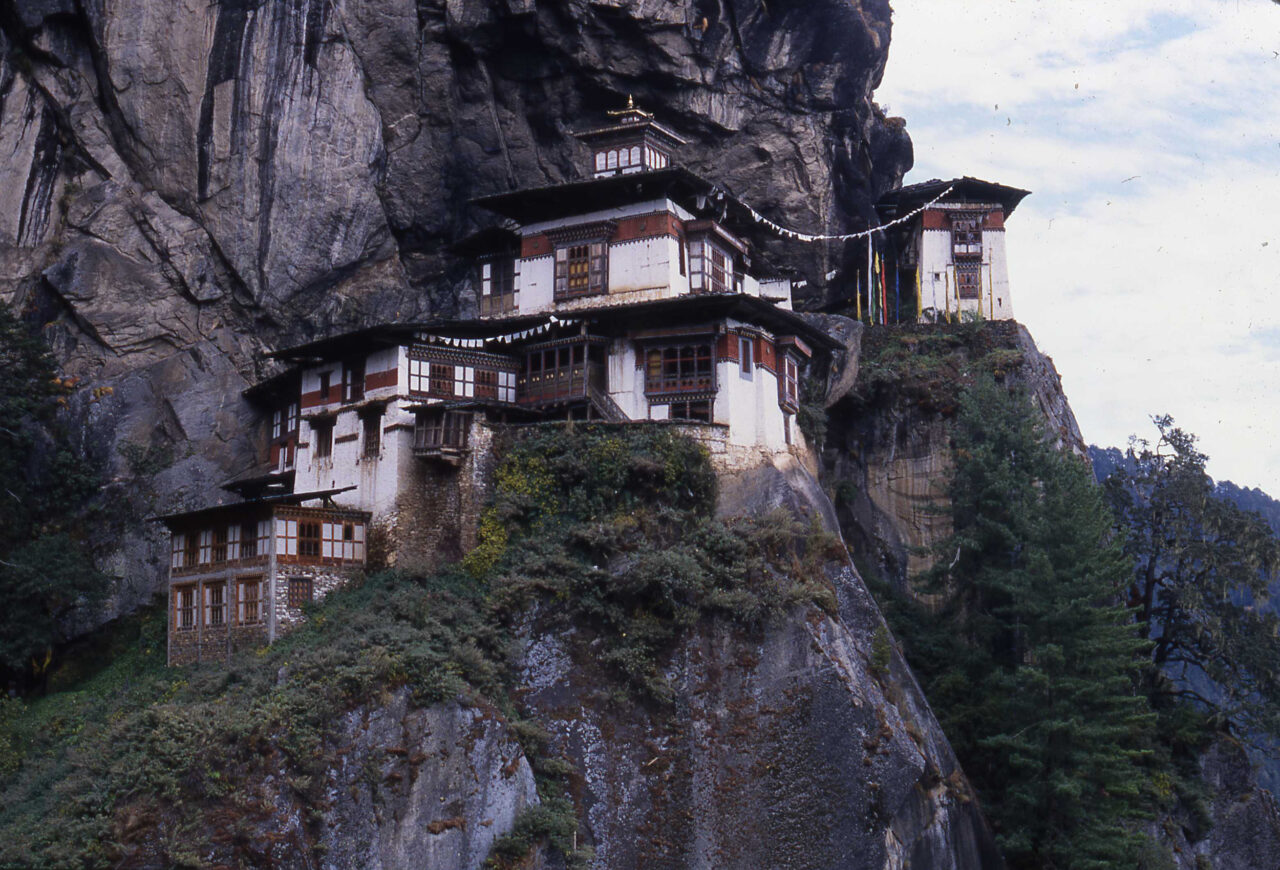

The Kagyu are a major Later Diffusion tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. The Kagyu trace their lineages back to the Mahasiddhas, the great tantric masters of medieval India. The Kagyu are known for their yogic practices, as well as the teaching of Mahamudra, or the “Great Seal.” The Kagyu tradition includes many different branches, such as the Karma, Drukpa, Drigung, Tselpa, Pakmodru, and others. The most influential leaders of the Karma Kagyu are the Karmapas, a tulku lineage associated with that Kagyu branch. In Bhutan, the Drukpa Kagyu tradition serves as the state religion. A follower of the Kagyu is called a Kagyupa.

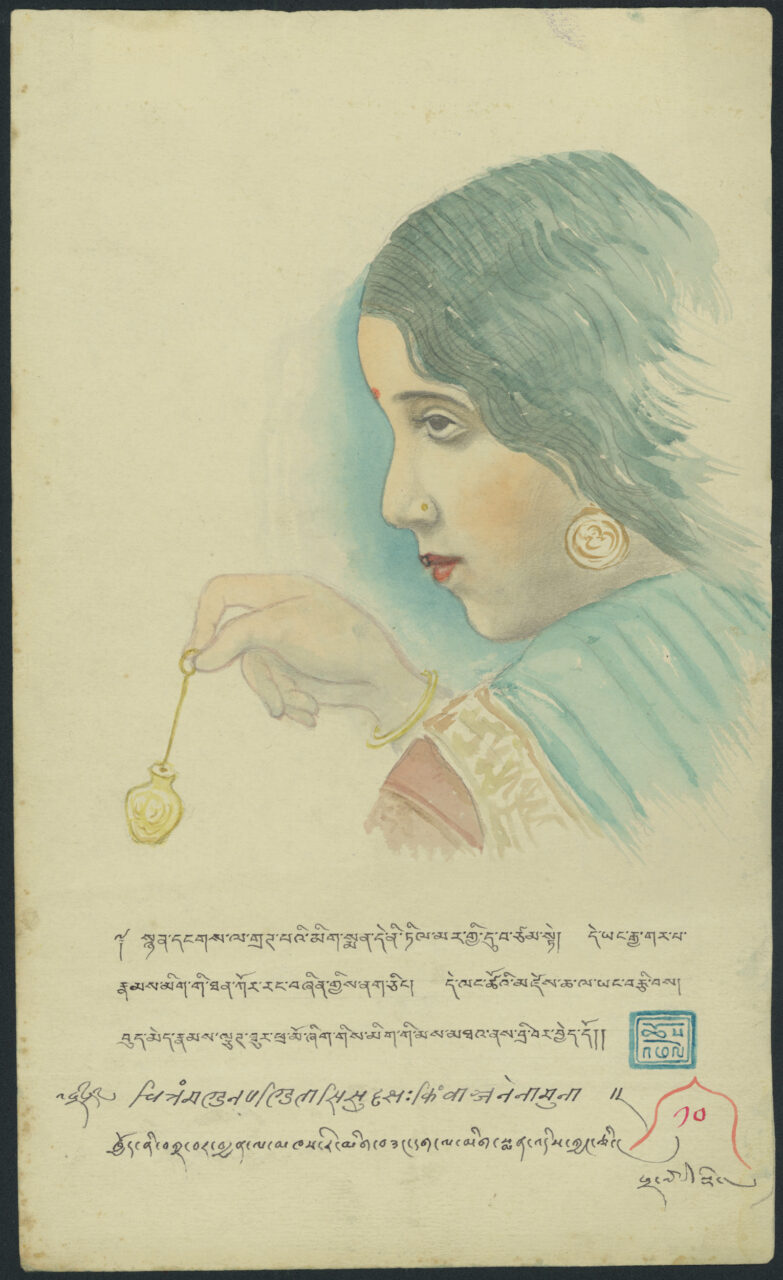

A practice of hiring and commissioning artists to create works of art. In religious context patrons were often rulers, religious leaders, as well as ordinary people. (see also donor)

Sakya is the name of a monastery and of a major tradition of Tibetan Buddhism that originated there during the Later Diffusion of Buddhism. Sakya Monastery was the seat of power during Sakya-Mongol rule in Tibet (1260–1350s), founded on the priest-patron relationship. Notable Sakya figures include Sakya Pandita (1182–1251), who played an instrumental role in establishing Tibetan relations with the Mongols; Drogon Chogyel Pakpa (1234-1280), who served as Qubilai Khan’s imperial preceptor and invented the Pakpa Script; and Buton (1290–1364), who compiled the Tibetan Canon. The Sakya are particularly known for their Lamdre teachings. In the 1350s, Pakmodru replaced the Sakya political prominence.

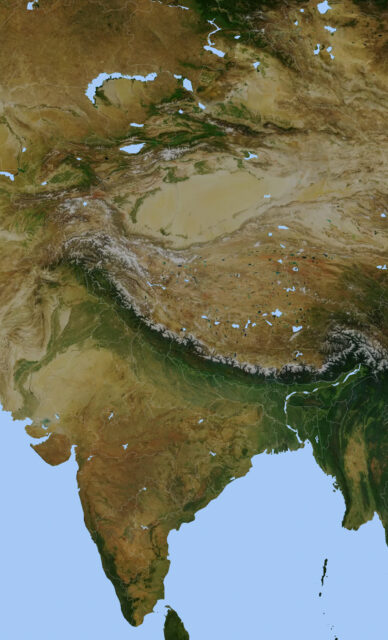

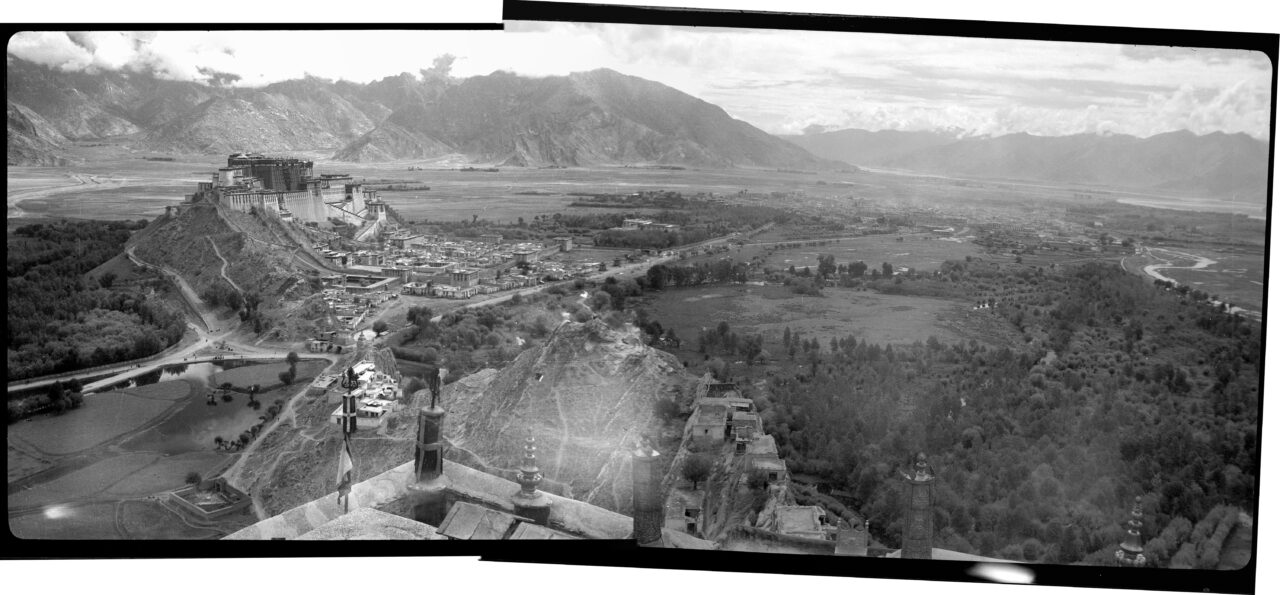

Historically, Tibetan Buddhism refers to those Buddhist traditions that use Tibetan as a ritual language. It is practiced in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, Ladakh, and among certain groups in Nepal, China, and Russia and has an international following. Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in two waves, first when rulers of the Tibetan Empire (seventh to ninth centuries CE), embraced the Buddhist faith as their state religion, and during the second diffusion (late tenth through thirteenth centuries), when monks and translators brought in Buddhist culture from India, Nepal, and Central Asia. As a result, the entire Buddhist canon was translated into Tibetan, and monasteries grew to become centers of intellectual, cultural, and political power. From the end of the twelfth century, Tibetans were exporting their own Buddhist traditions abroad. Tibetan Buddhism integrates Mahayana teachings with the esoteric practices of Vajrayana, and includes those developed in Tibet, such as Dzogchen, as well as indigenous Tibetan religious practices focused on local gods. Historically major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism are Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Geluk.

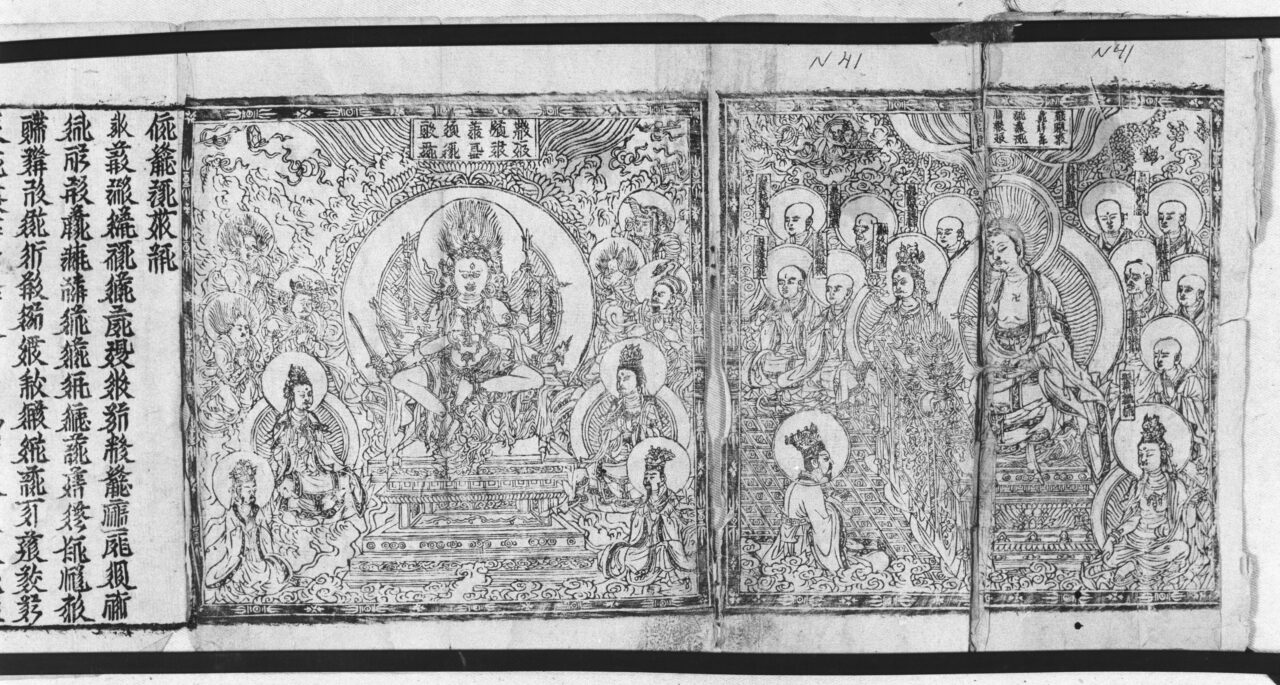

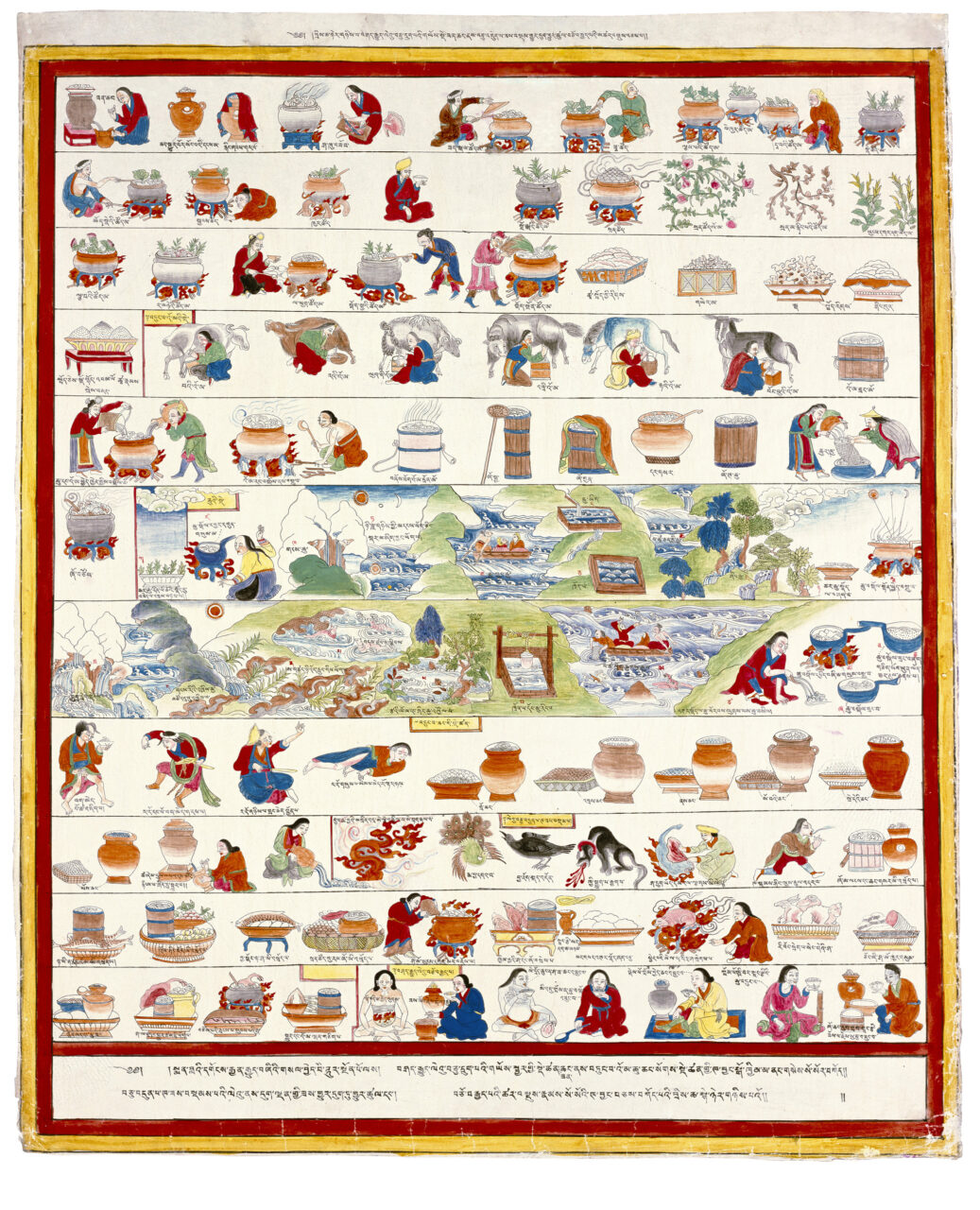

The Vajravali is a collection of esoteric teachings on mandala construction written by the Indian monk Abhayakaragupta (eleventh to twelfth centuries). The Vajravali was the first attempt to systematize and provide iconographic guides for the mandalas used in various Vajrayana tantras, which were widely transmitted in Tibet.

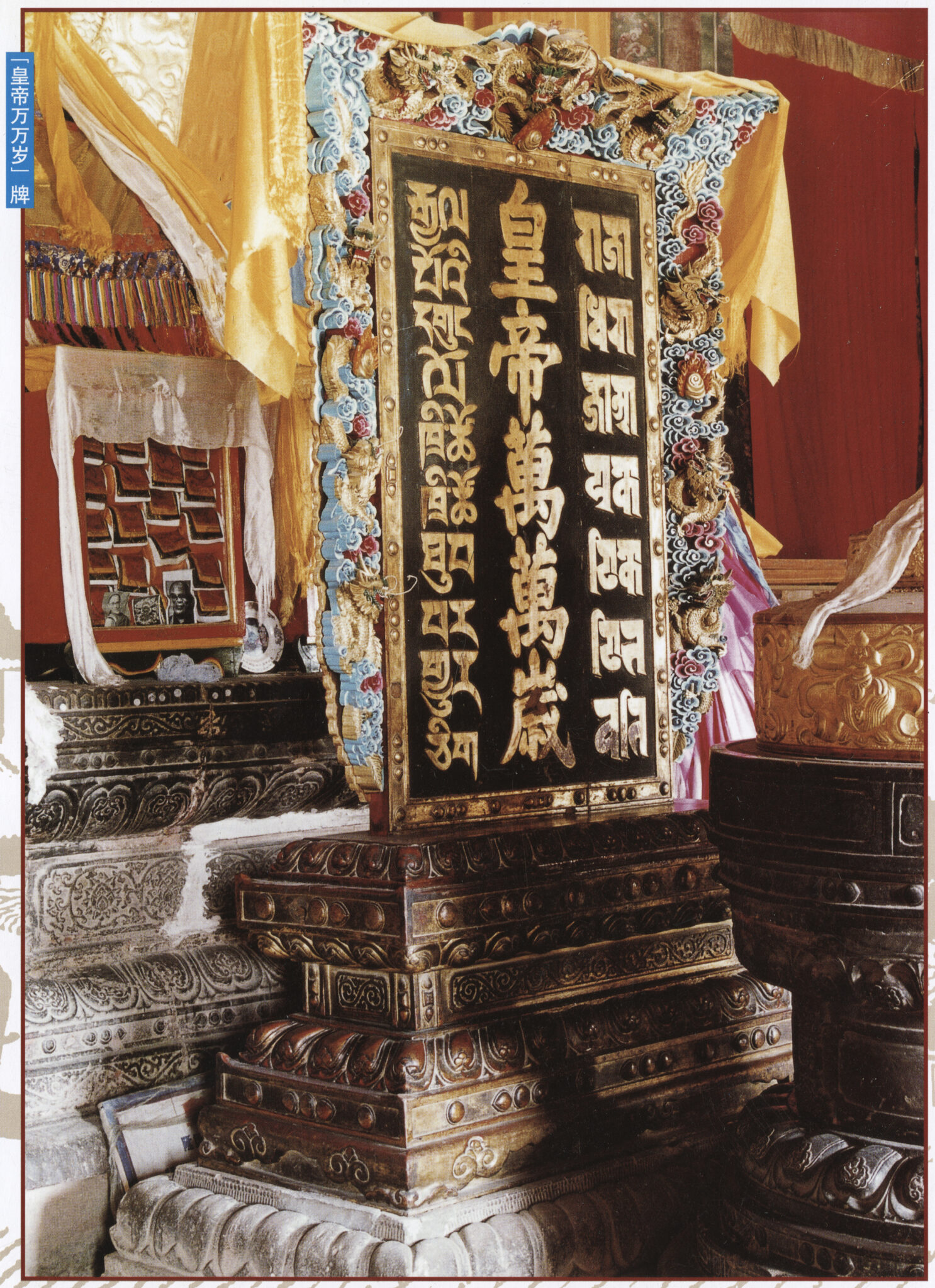

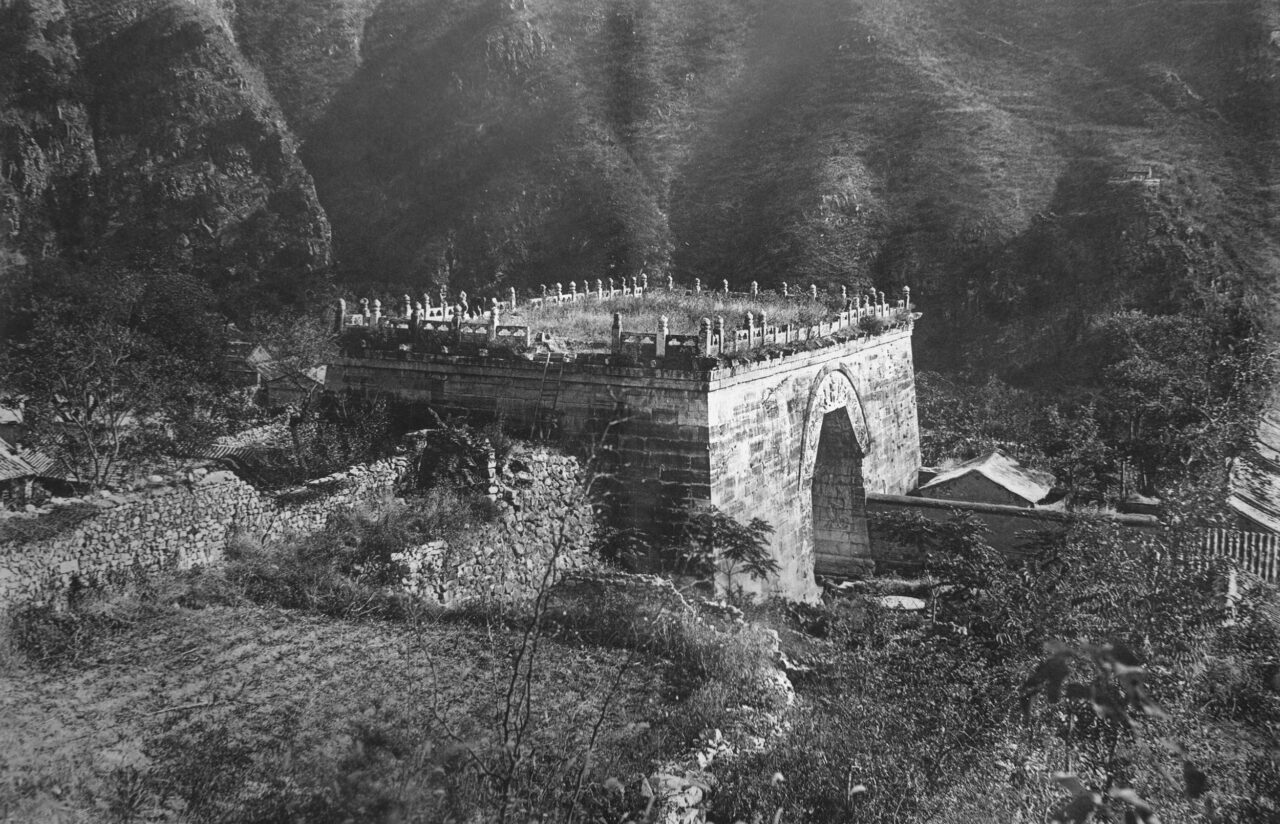

The Ming dynasty was a Chinese state that existed from 1368 to 1644 CE. The Ming founder, Zhu Yuanzhang (1328–1398), led an army that defeated the Yuan dynasty of the Mongol Empire and restored ethnic Chinese rule in China. Unlike the Mongols before them or the Qing dynasty after them the Ming never seriously attempted to rule the Tibetan regions, preferring instead to manage border affairs by granting titles and trading rights to friendly Tibetan monks and secular leaders. Nevertheless, several early Ming emperors had close personal relations with Tibetan lamas, and relations of trade and cultural interchange flourished between Chinese and Tibetan regions.