The Dalai Lamas are a tulku lineage that has played a central role in Tibetan history for the last five hundred years. In 1577 a Mongol khan gave the Geluk monk Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588) the title “Dalai Lama,” combining the Mongolian word for ocean, dalai (a reference to the depth of his knowledge), and the Tibetan word for guru, lama. Later, two previous incarnations were retroactively identified. The fifth incarnation, Ngawang Gyatso (1617–1682), allied with another Mongol khan to unite most of the Tibetan Plateau, forming the Ganden Podrang government that would govern Tibet until 1959. Since the Communist takeover, the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama has lived in exile at Dharamshala in India. The Dalai Lamas are understood to be emanations of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

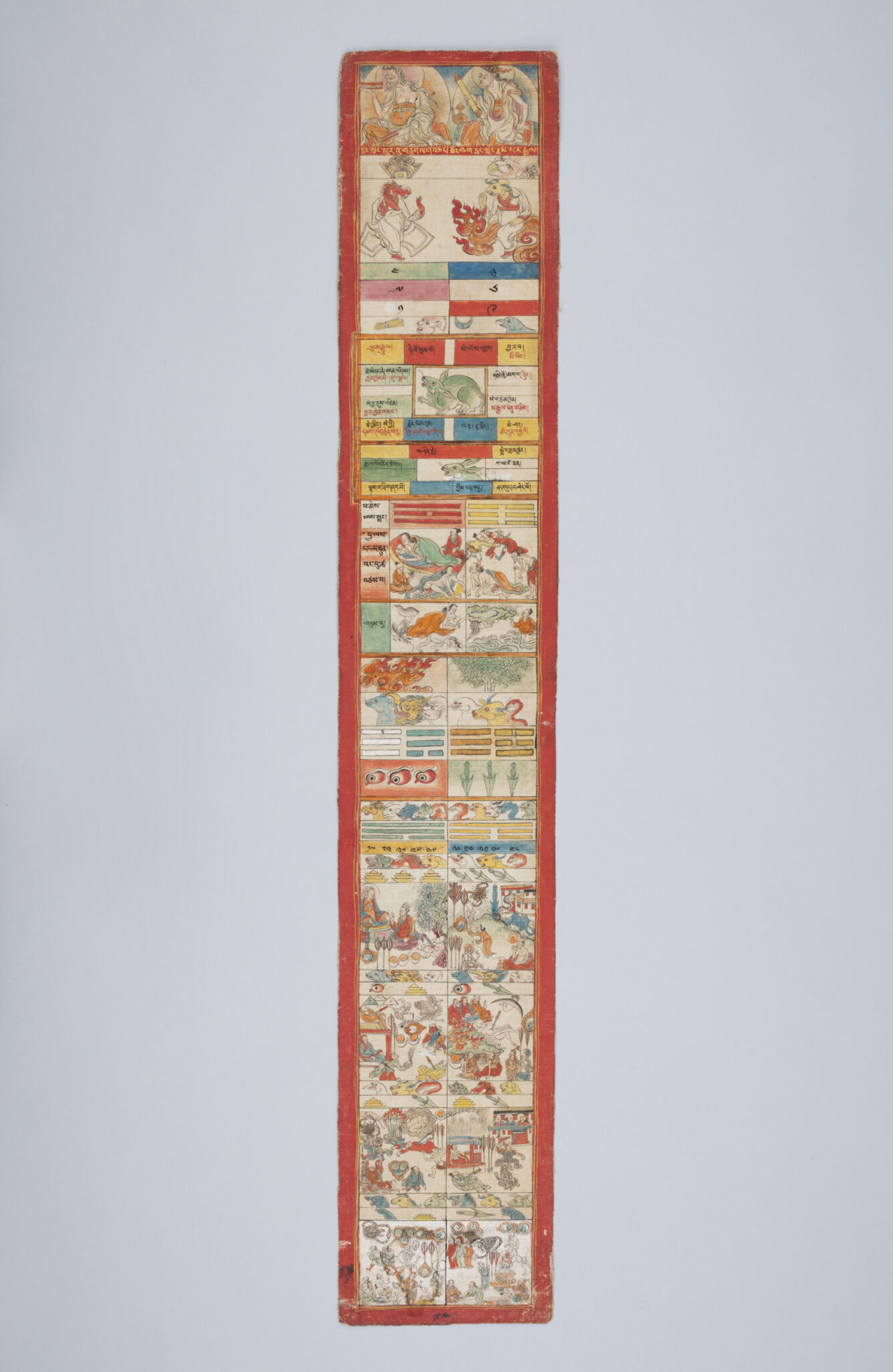

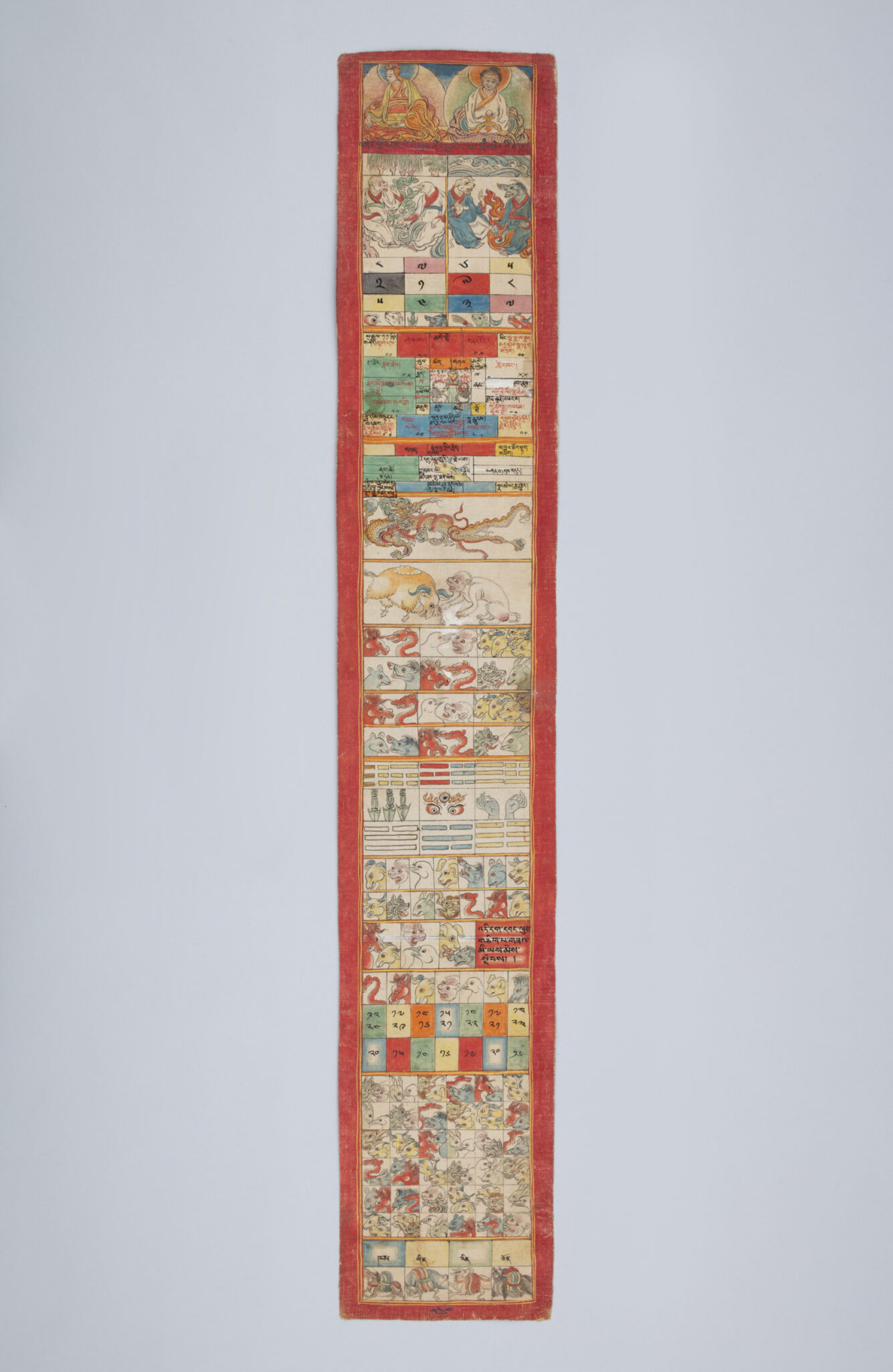

Divination refers to any supernatural means of knowing the world, including oracles, astrology, and geomancy (the study of forces in the landscape).

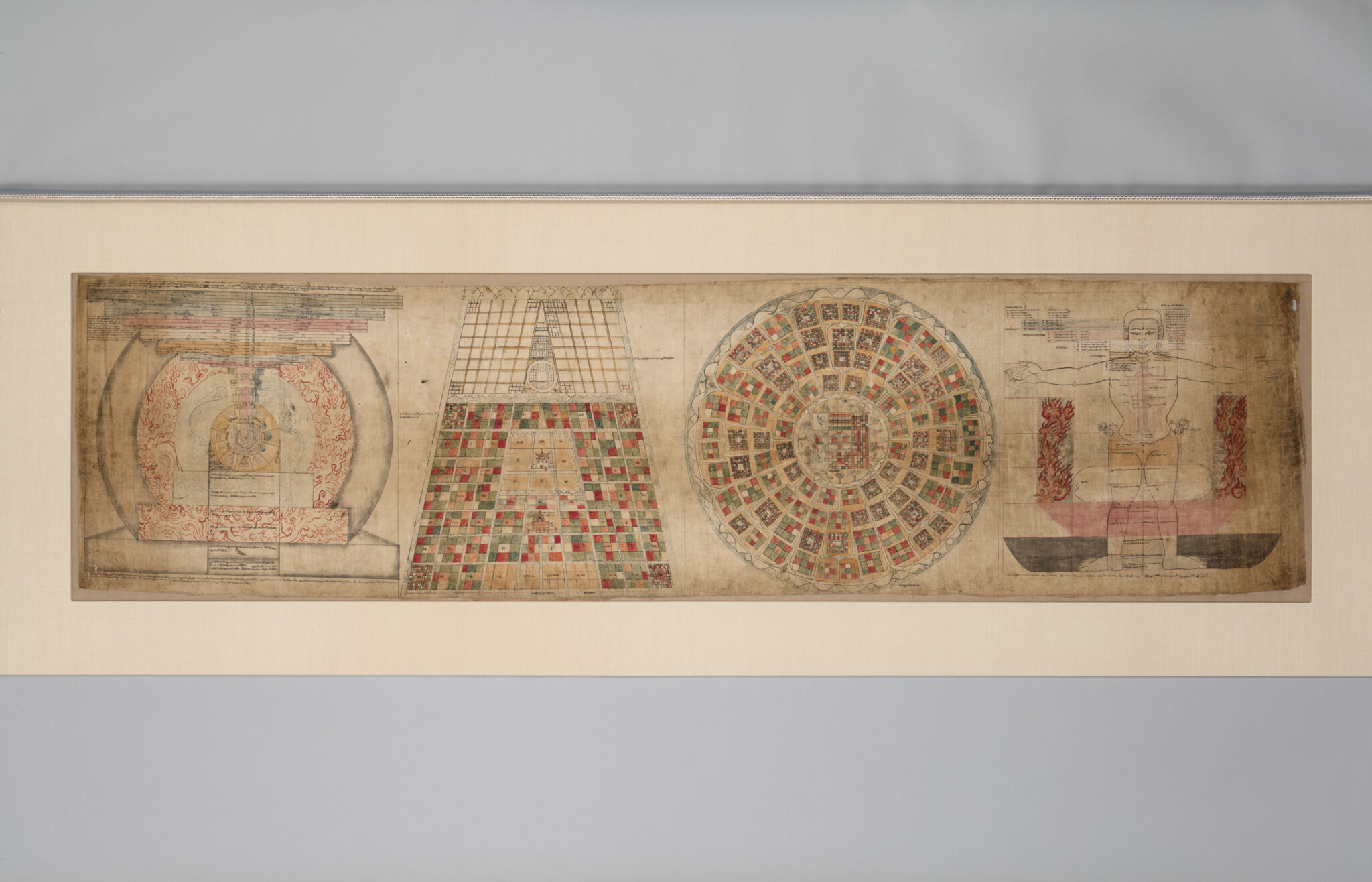

Kalachakra refers to both the name of major Highest Yoga tantra texts and the central deity, which is the focus of these texts, depicted as a multi-armed figure in tantric union with his consort Vishvamata. The tantra’s elaborate cosmology addresses three wheels of time—the outer, inner, and the other. The outer wheel of time refers to the external world, procession of the external solar and lunar days, or the macrocosm. The inner wheel of time refers to the human body or the microcosm of the inner channels, elements, and wind movements. And the other wheel is the initiation into the paths and the practice. According to the text the Buddha first taught, the Kalachakra tantra in the mythical Buddhist realm of Shambhala to chakravartin kings who rule there.

Hinduism and Buddhism both hold that actions (Skt. karma) have inevitable results which may take a shorter or longer time to occur. Mental, verbal, and physical actions all have positive or negative consequences and are considered karma. Depending on conditions, karma can manifest results either in this or future lives. Karma directly relates to the idea of reincarnation, and positive karma can also create religious merit and lead to a better rebirth, while negative actions, or karma, result in worse experiences in the present and future lives. Buddhists strive to achieve enlightenment to escape this cycle of karmic action and consequence.

Sakya is the name of a monastery and of a major tradition of Tibetan Buddhism that originated there during the Later Diffusion of Buddhism. Sakya Monastery was the seat of power during Sakya-Mongol rule in Tibet (1260–1350s), founded on the priest-patron relationship. Notable Sakya figures include Sakya Pandita (1182–1251), who played an instrumental role in establishing Tibetan relations with the Mongols; Drogon Chogyel Pakpa (1234-1280), who served as Qubilai Khan’s imperial preceptor and invented the Pakpa Script; and Buton (1290–1364), who compiled the Tibetan Canon. The Sakya are particularly known for their Lamdre teachings. In the 1350s, Pakmodru replaced the Sakya political prominence.