Buddhism is founded on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, who lived sometime between the sixth and fourteenth century BCE in northern India. Buddhists believe that sentient life is a cycle of suffering and rebirth, but that if one achieves a state of awakening or nirvana, it is possible to escape this cycle. Buddhists refer to the Buddha’s teachings as the Dharma. There are many different traditions or denominations of Buddhism, including Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. Scholars also discuss regional traditions, such as Indian Buddhism, Newar Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Chinese Buddhism, and so on.

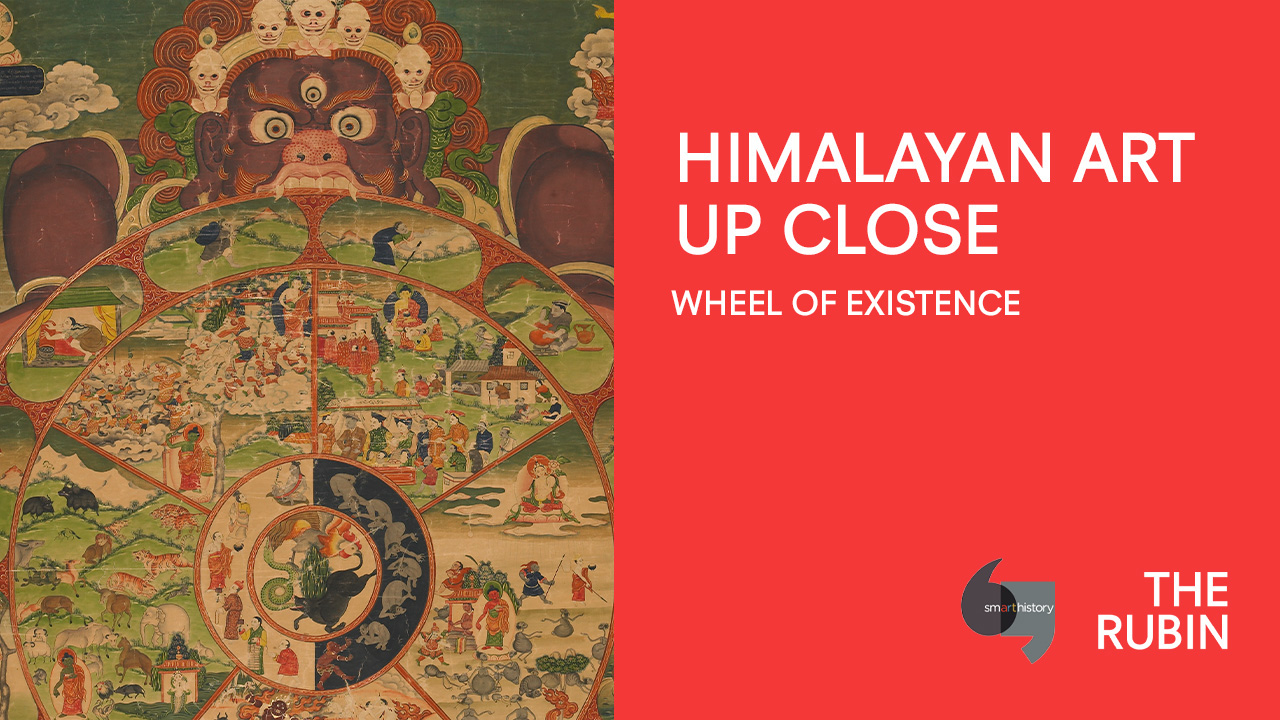

Wheels are an important symbol in Buddhism, which often refers to the Buddha’s teachings as “turning the wheel of the Dharma.” When depicted in the hands of a deity or human, a wheel can also denote political power, symbolizing the chakravartin or universal ruler. In the Hindu tradition, the chakra is an ancient weapon, carried by gods such as Vishnu. Chakras can also refer to focal points in the human body; in both Hindu and Buddhist systems of yogic meditation, practitioners channel the energies of the body through these points to obtain higher states of consciousness.

In Buddhism, the hell realms are the lowest portions of samsara, or the wheel of reincarnation. Different texts give different accounts of these realms, but a standard list says that there are eight cold and eight hot hells. Beings are reborn into these realms due to their negative karma, and although they may spend many eons there, eventually they will die and be reborn elsewhere.

Impermanence is a core concept in Buddhism. The Buddha taught that all beings, things, and thoughts are constantly appearing, changing, and passing away in samsara. We suffer because we are attached to these unstable things. In Madhyamaka philosophy, impermanence is a central part of the doctrine of emptiness.

Hinduism and Buddhism both hold that actions (Skt. karma) have inevitable results which may take a shorter or longer time to occur. Mental, verbal, and physical actions all have positive or negative consequences and are considered karma. Depending on conditions, karma can manifest results either in this or future lives. Karma directly relates to the idea of reincarnation, and positive karma can also create religious merit and lead to a better rebirth, while negative actions, or karma, result in worse experiences in the present and future lives. Buddhists strive to achieve enlightenment to escape this cycle of karmic action and consequence.

Nirvana is said to be a state beyond the cycle of reincarnation (Skt. samsara). It is defined as the end of suffering of being born, living, dying, and being reborn, and the ultimate goal for Buddhist practitioners. The Buddha achieved this state meditating beneath the bodhi tree, and his followers aim to advance to that state by gradually clearing out their karmic limitations. Different Buddhist traditions variously characterize nirvana, indicting several levels of awakening, from achieving peace to utterly transcending both the suffering of samsara and the peace of nirvana.

In Buddhism and Hinduism, samsara is the phenomenal world in which we live, and the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. In Buddhism, samsara refers to the six realms of existence in which beings can be born according to their karma: as hell beings, hungry ghosts, animals, humans, demi-gods (Skt. asura), and gods. The central goal of Buddhism is to escape the suffering of samsara by achieving nirvana, a state beyond this cycle of rebirths.