The Eight Great Events are eight scenes from the life of Buddha Shakyamuni that became a standard part of his iconography in India and Nepal. The eight events are:

- The birth of the Buddha

- His awakening (enlightenment)

- His first sermon

- A monkey offers him honey

- He tames a wild elephant

- Descending from the Heaven of the Thirty-Gods

- Defeating heretical sects by miraculous displays

- The Buddha’s death (Skt. parinirvana)

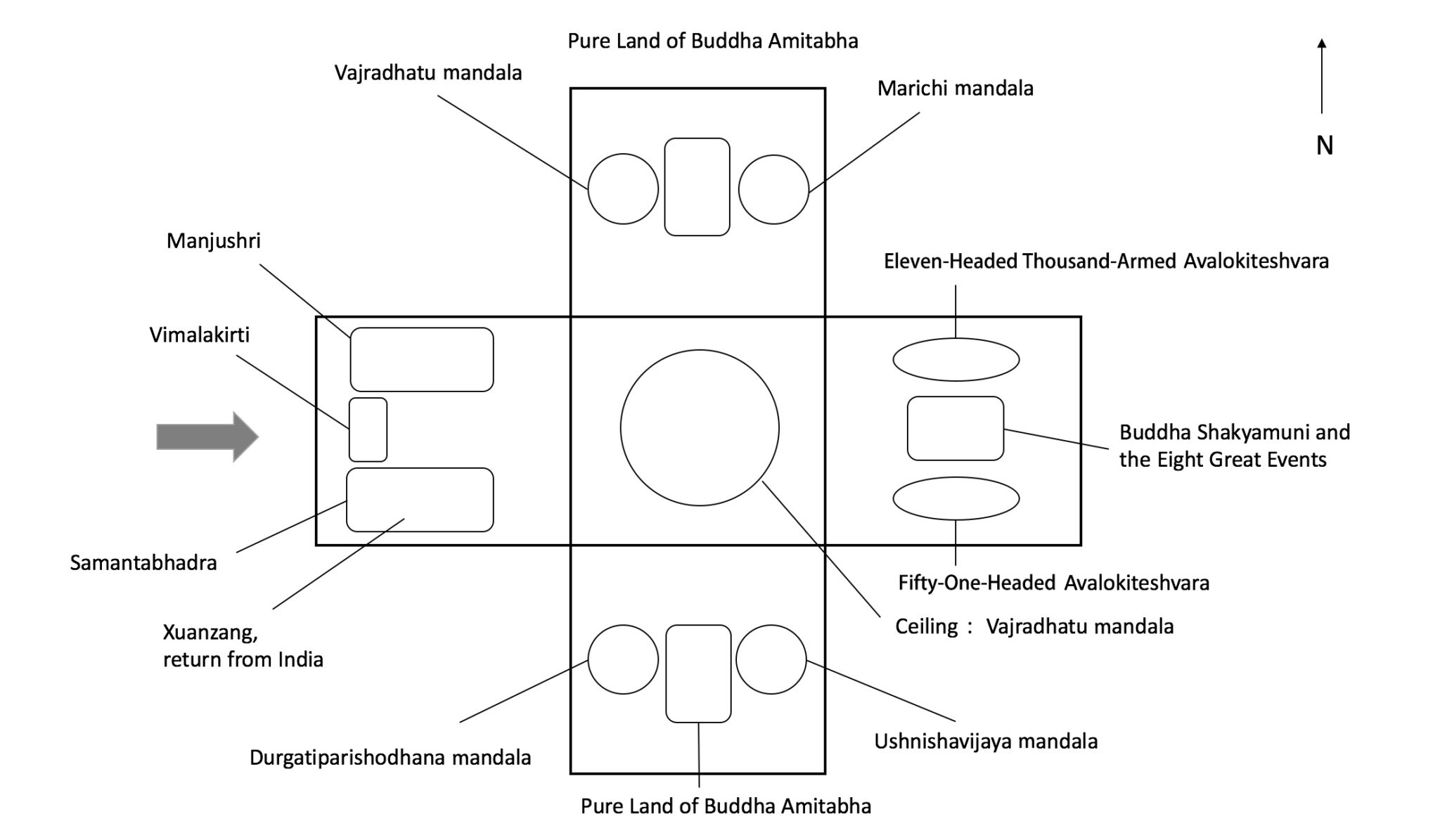

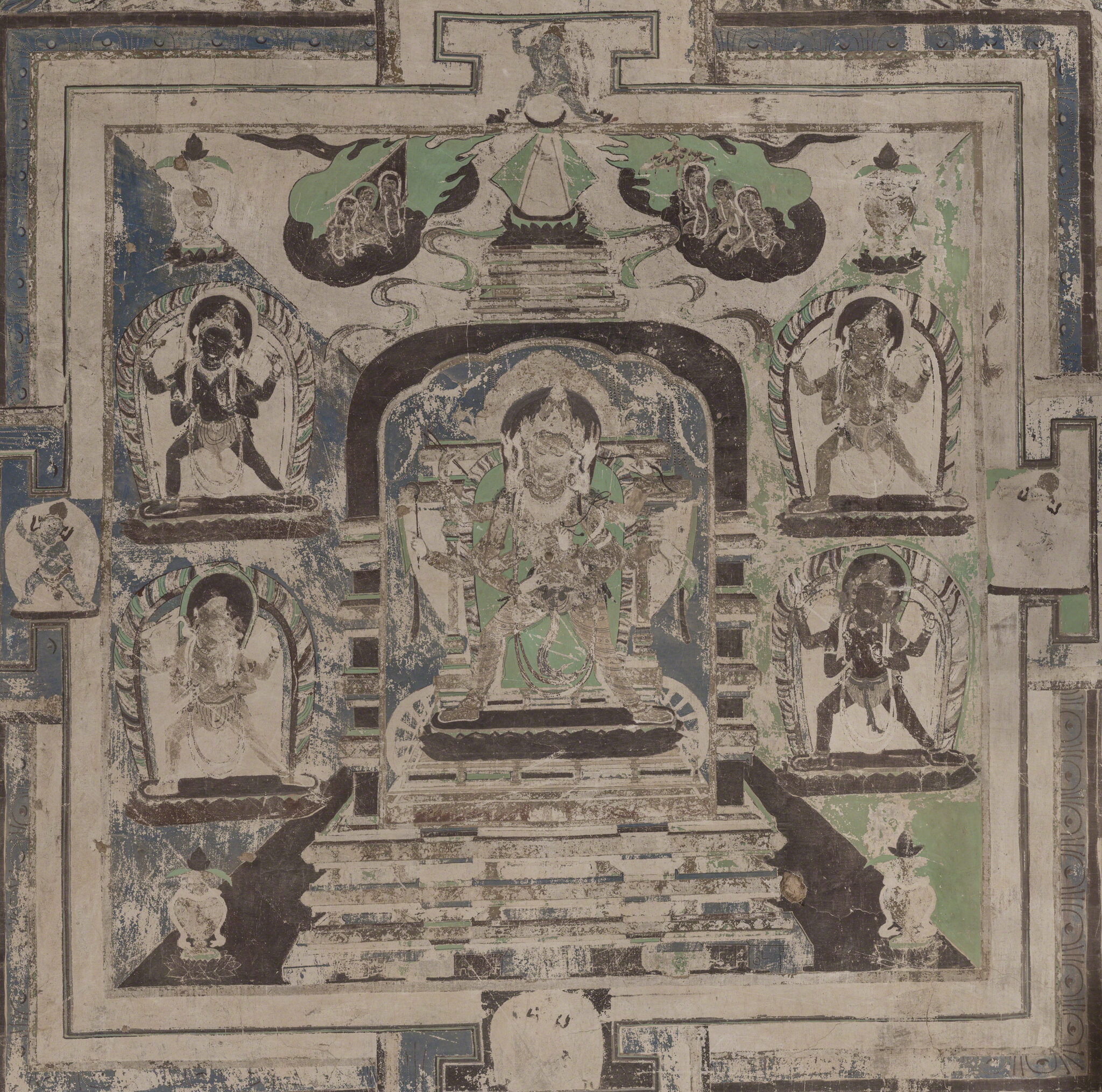

In Vajrayana Buddhism or Bon, a mandala refers to a cosmic abode of a deity, usually depicted as a diagram of a circle with an inscribed square that represents the deity enthroned in their palace, surrounded by members of their retinue. Mandalas can be painted, three-dimensional models, architectural structures, such as temples or stupas, or composed as arrangements of images within a temple. The instructions for creating and visualizing mandalas are usually found in ritual texts, such as tantras and sadhanas. Mandalas can be used in initiation ceremonies, visualized by a practitioner as part of deity yoga, consecrated and used to represent the divine presence within ritual space, offered to the deities as representations of the entire universe. A similar concept in Hinduism is a yantra.

A practice of hiring and commissioning artists to create works of art. In religious context patrons were often rulers, religious leaders, as well as ordinary people. (see also donor)

“Silk Roads” is a term broadly used to describe the long-distance trade routes across Central Asia that connected the Indian Subcontinent with East Asia and the Mediterranean world. These trade routes were highly important in transmitting both art and ideas across the Asian continent, including the Buddhist religion. There were many “silk roads”—some crossed the deserts of Central Asia, other maritime routes also connected Europe, the Middle East, Africa, South, Southeast, and East Asia.

Stupas are monuments that initially contained cremated remains of Buddha Shakyamuni or important monks, his disciples, and subsequently other material and symbolic relics associated with the Buddha’s body, teaching, and enlightened mind. As representations of the Buddha’s presence in the world, stupas with their contents—texts, relics, tsatsas—continue to be important objects of Buddhist worship in their diverse forms of domed structures, multistoried pagodas, and portable sculptures. The original form of stupas was an earthen dome-shaped mound containing the remains in reliquary vessels or urns deposited within the innermost core. The dome would often be successively enlarged and surrounded by a path for a walk around in a clockwise direction and veneration (circumambulation)

The Tanguts were an ethnic group in medieval East-Central Asia, who called themselves Minyak and spoke a language distantly related to Tibetan. Between 1038 and 1227 CE the Tanguts ruled a state in what is now the Chinese provinces of Ningxia, Gansu, and Qinghai. This state took the Chinese dynastic name of Xia, also called Xixia “Western Xia.” The Tangut-Xixia emperors were major patrons of Buddhism, inviting both Chinese and Tibetan monks to teach in the capital, and instituting major Buddhist translation and printing projects in three languages. The Tangut state was destroyed by the armies of Chinggis Khan, leading to their absorption into the Mongol Empire, where many Tanguts served as officials.