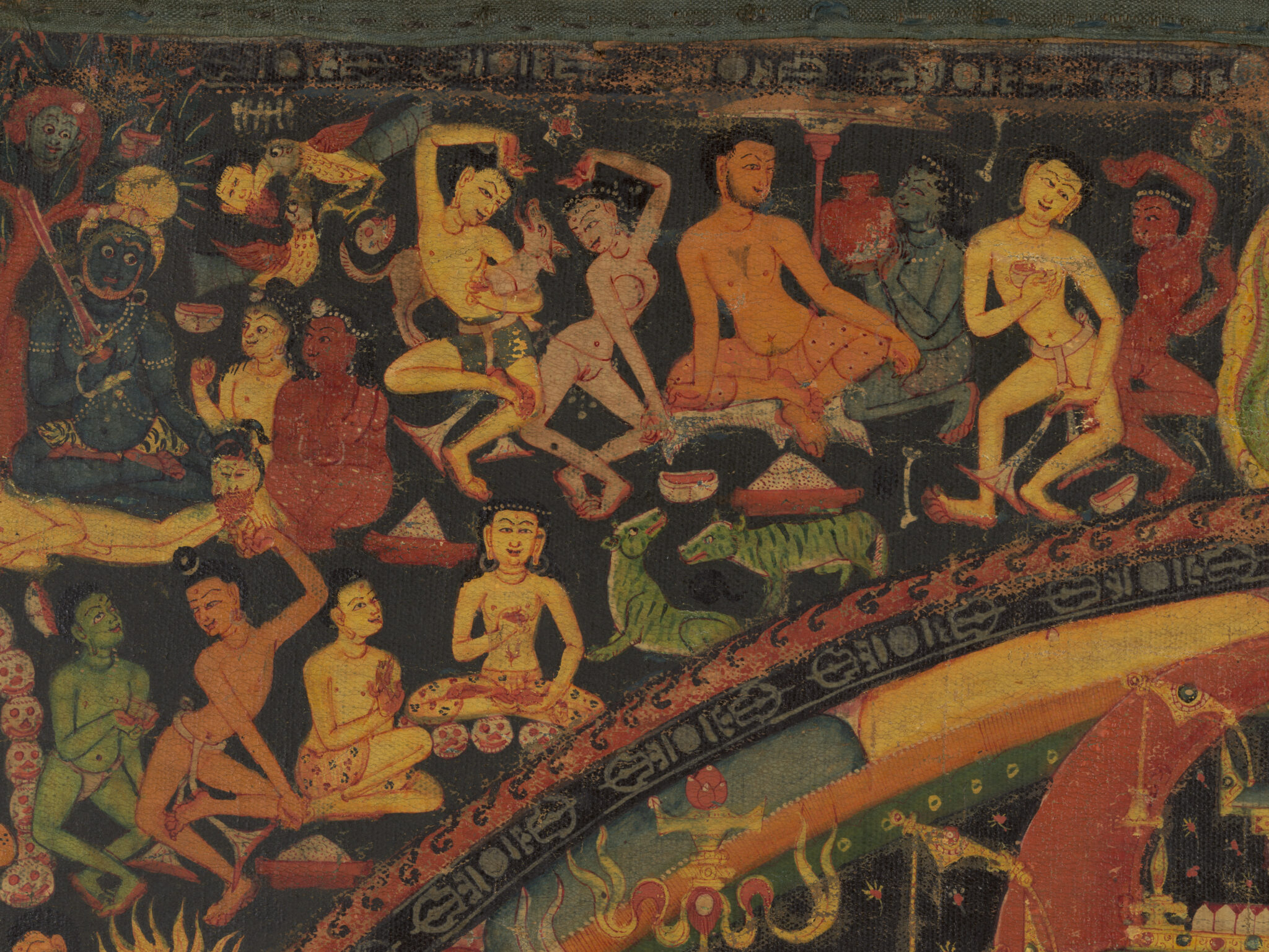

In India and Tibet, a charnel ground is a place where dead bodies are brought for cremation or exposure to be consumed by vultures. In early Buddhism, practitioners would come to these places to meditate on death and impermanence. In tantric forms of Hinduism and in Vajrayana Buddhism, these charnel grounds became an important gathering place for yogins, and a source of transgressive imagery for iconographies of tantric deities and the siddhas who embody these practices.

In tantric Hinduism and Vajrayana Buddhism, a “siddha” is one who has mastered “siddhis,” or the magical powers that come with yogic practice. The “Great Siddhas” (mahasiddhas) were a semi-mythical group of tantric masters, men and women, who lived in medieval India. They were known for their extraordinary meditative powers, religious poetry, and their transgressive lifestyles, including dwelling in charnel grounds, drinking alcohol, fighting, and having sex. Many Himalayan Vajrayana traditions trace their initiation lineages back to the Mahasiddhas. Depictions of sets of eight, eighty-one, or eighty-four Mahasiddhas are a popular subject in Himalayan art.

The Newar People of the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal retain the unbroken traditions of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism south of the Himalayas, preserving many ritual practices and Sanskrit-language texts that have been lost elsewhere. Celibate monasticism is no longer practiced among the Newars, but instead Buddhist ritualists are divided into two castes. One is the Shakyas, temple-priests who maintain ancient urban monasteries (Newar: bahas, bahis) as places of worship. The other is the Vajracharyas, tantric specialists who perform rituals at communal festivals and important life events. The Svayambhu Stupa is the most important ritual center for Newar Buddhists and the center of the Kathmandu Mandala. Today many Newars also practice Theravada and Tibetan Buddhism.

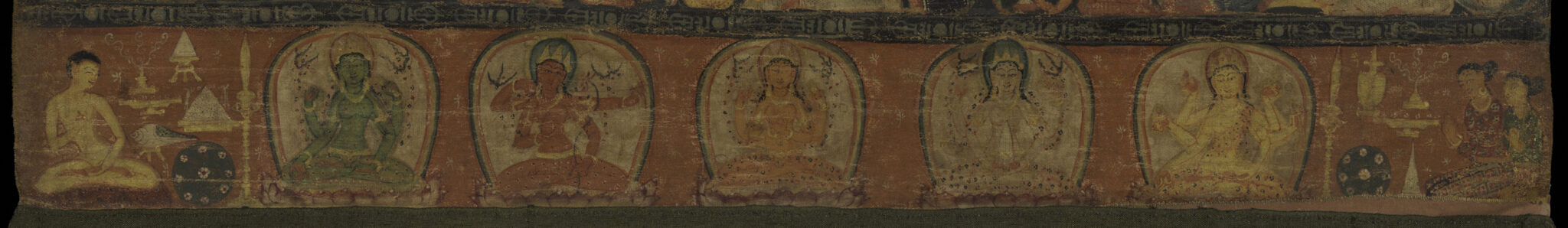

Religious painting, usually on cloth, in the form of a hanging scroll.

In Buddhism and Hinduism, sadhana is any yogic or meditative practice that leads towards enlightenment. Sadhana also refers to a particular type of text that gives practical instructions for how the practitioner should go about performing the rituals and visualizations, including detailed descriptions of the deities’ iconography and their mandala.

A thangka is a Tibetan hanging scroll, usually painted on cotton, and then mounted in a silk brocade mount. Thangkas can also be textiles woven or assembled in the appliqué technique. Thangkas are often kept rolled up around a wooden dowel affixed to the bottom end of the silk mounting, which also helps keep the scroll flat when hung. Almost all thangkas show religious subjects. Similar paintings produced in Nepal are called “paubha.”