Vases are an important part of ritual paraphernalia and the iconography of many deities; they are often understood to contain the elixir of life. The central bulb of a stupa is often also called a “vase.”

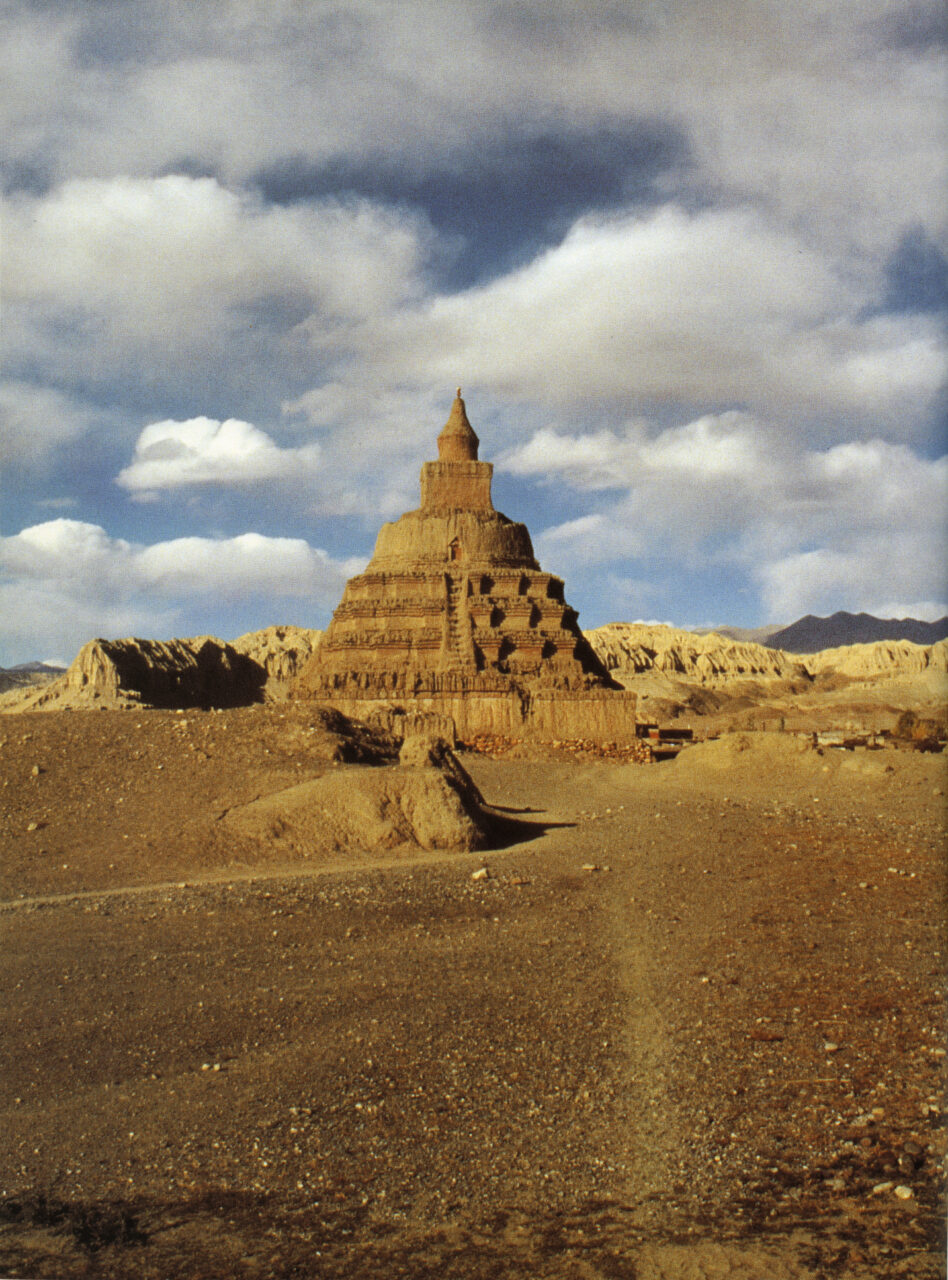

A harmika is an architectural element that forms a square balustrade section on top of the dome (Sanskrit: anda) of a stupa, and encloses the spire (Sanskrit: yasti) that rises above it. The harmika represents a divine abode.

A practice of hiring and commissioning artists to create works of art. In religious context patrons were often rulers, religious leaders, as well as ordinary people. (see also donor)

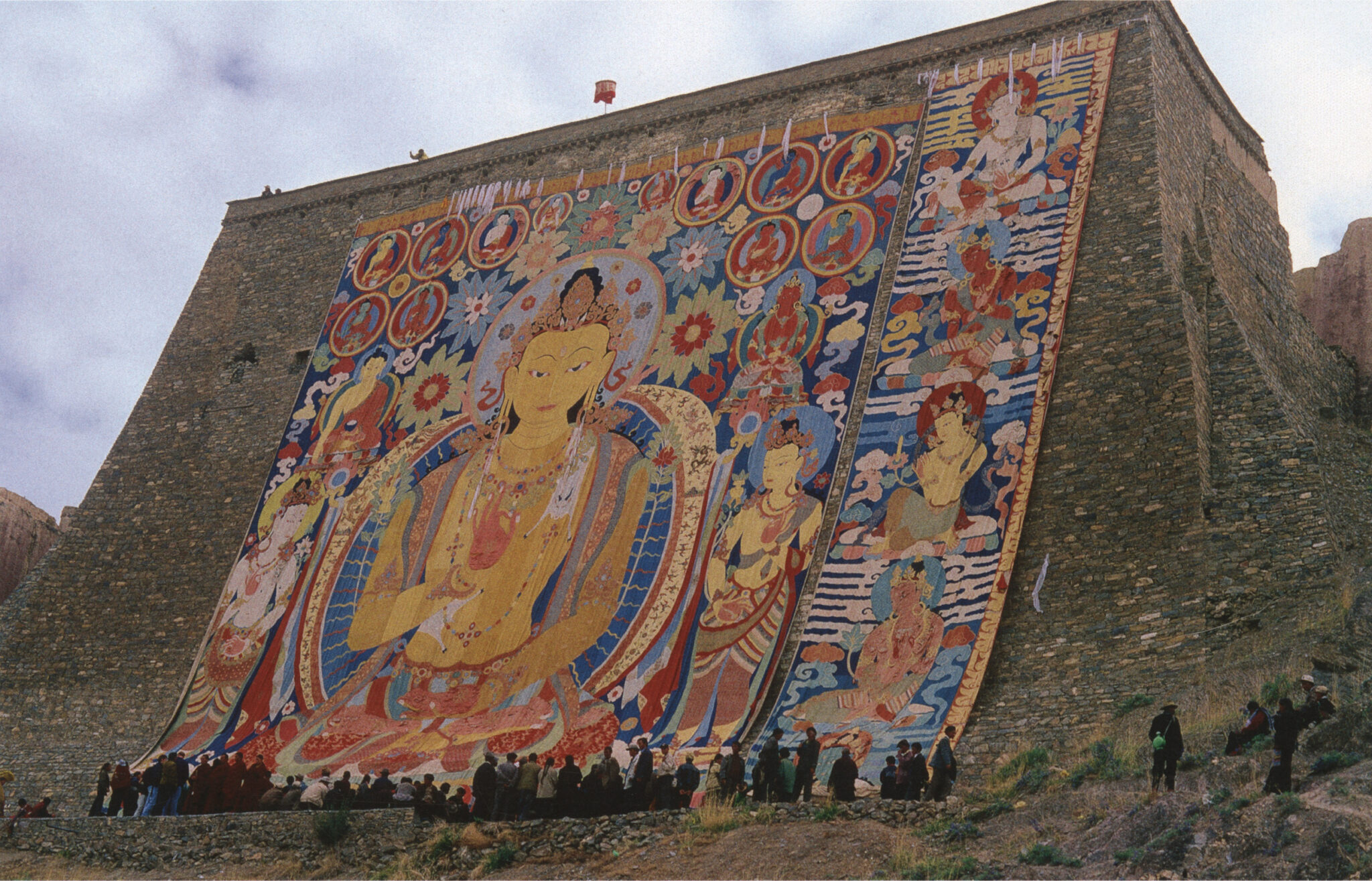

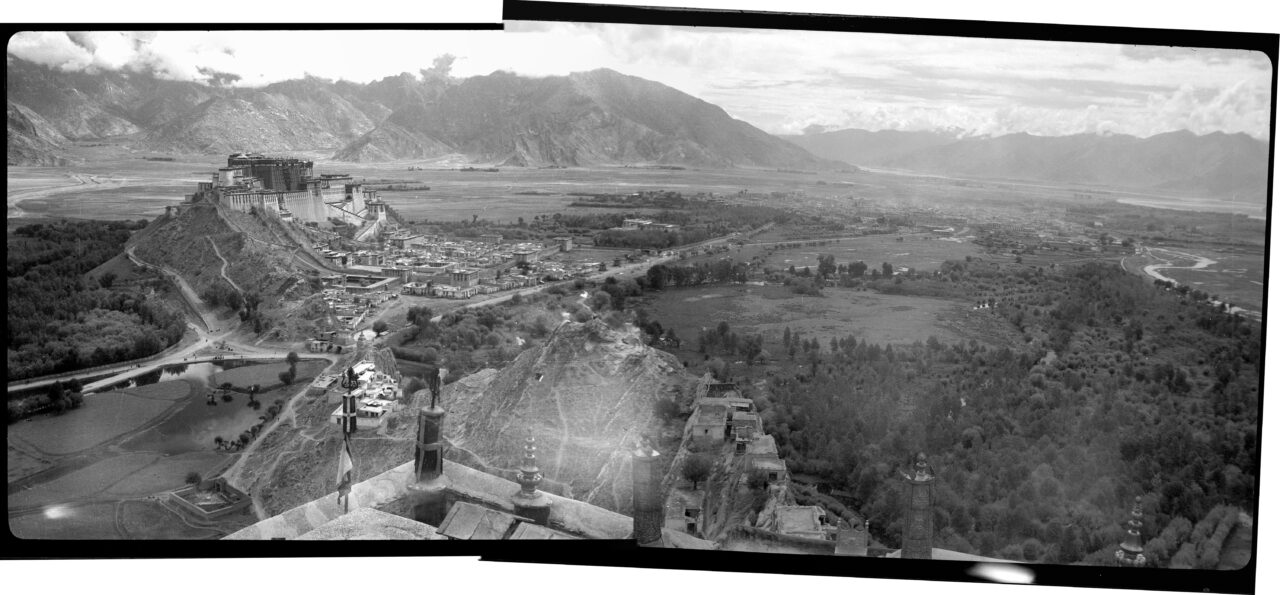

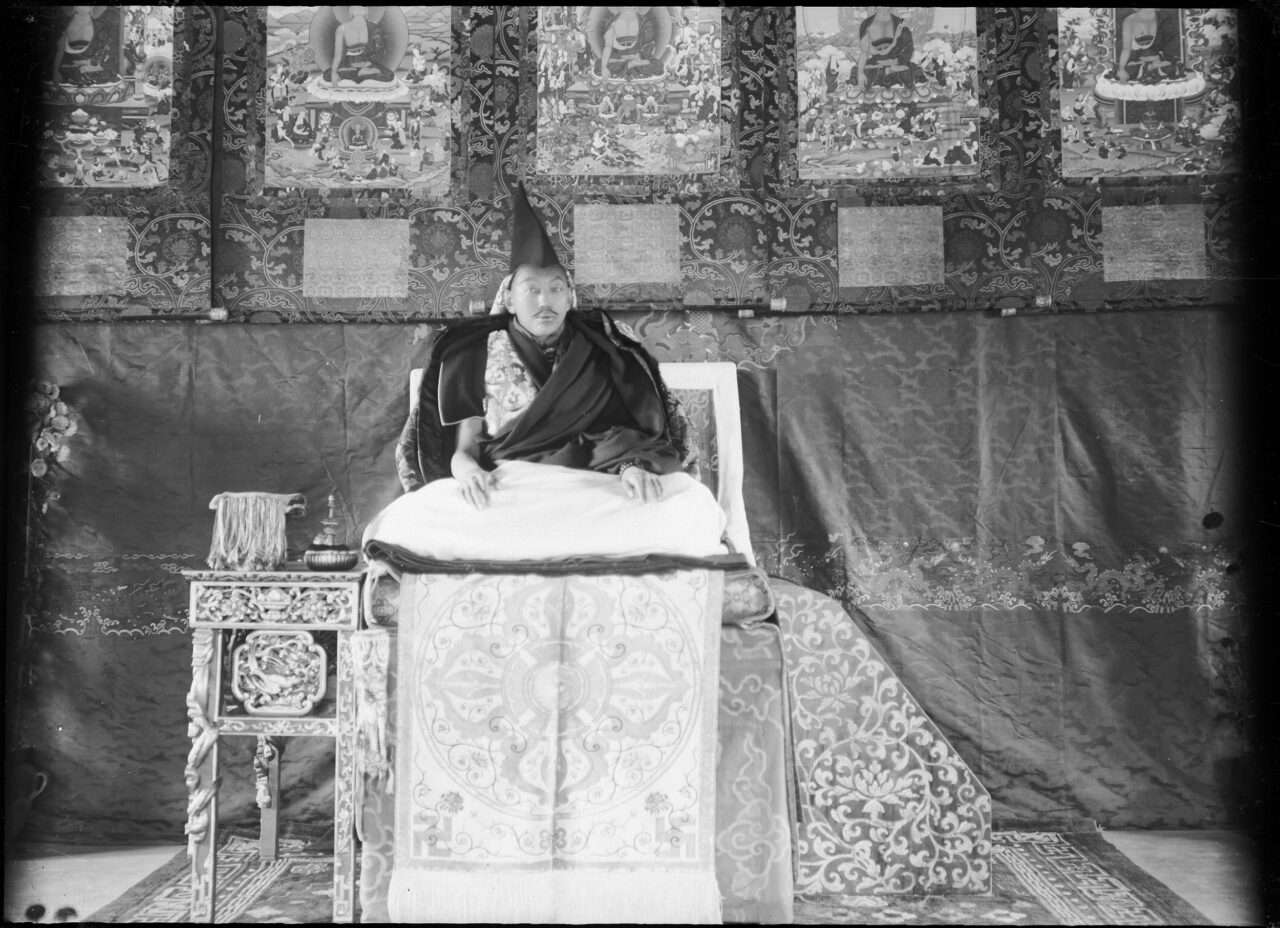

Sakya is the name of a monastery and of a major tradition of Tibetan Buddhism that originated there during the Later Diffusion of Buddhism. Sakya Monastery was the seat of power during Sakya-Mongol rule in Tibet (1260–1350s), founded on the priest-patron relationship. Notable Sakya figures include Sakya Pandita (1182–1251), who played an instrumental role in establishing Tibetan relations with the Mongols; Drogon Chogyel Pakpa (1234-1280), who served as Qubilai Khan’s imperial preceptor and invented the Pakpa Script; and Buton (1290–1364), who compiled the Tibetan Canon. The Sakya are particularly known for their Lamdre teachings. In the 1350s, Pakmodru replaced the Sakya political prominence.

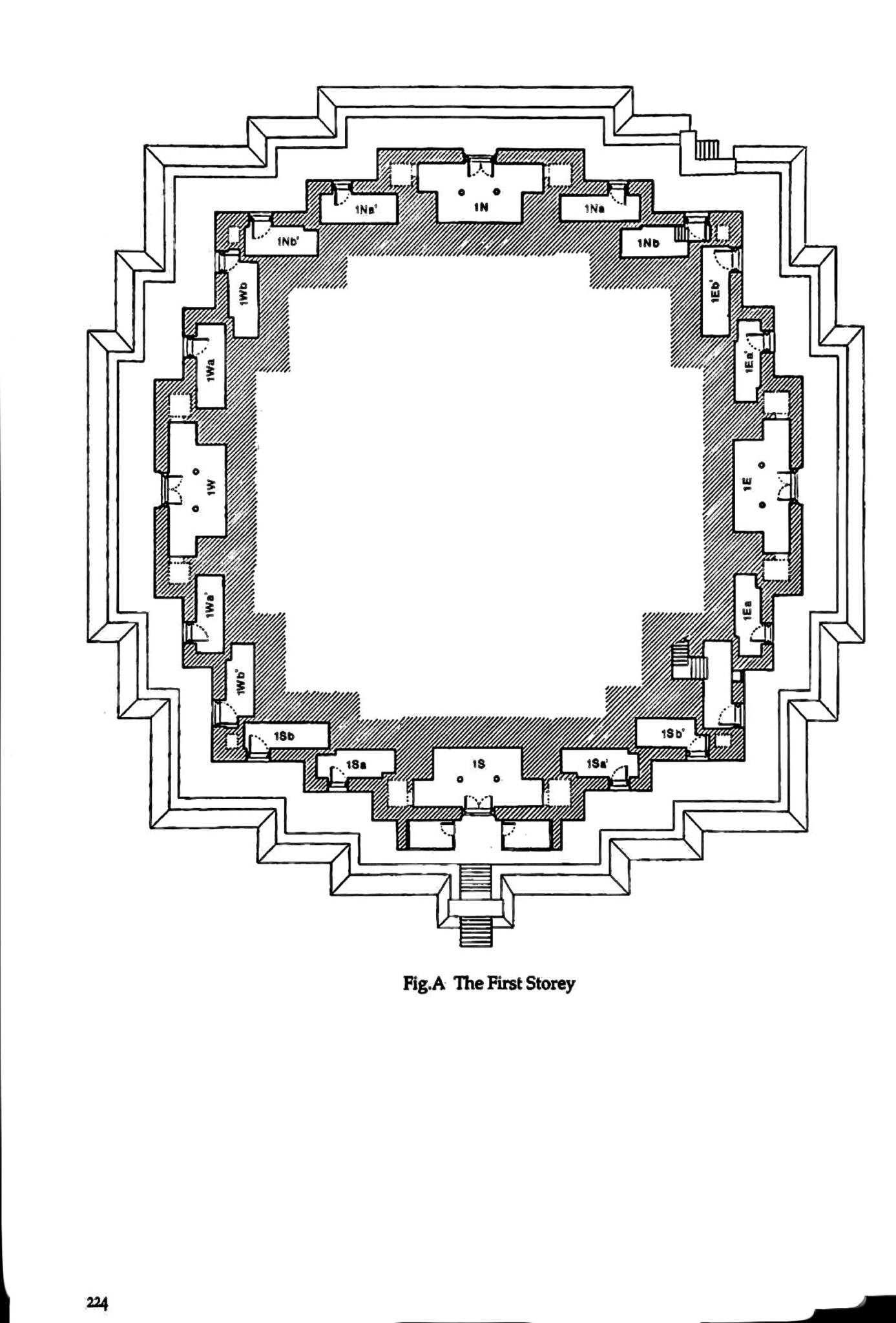

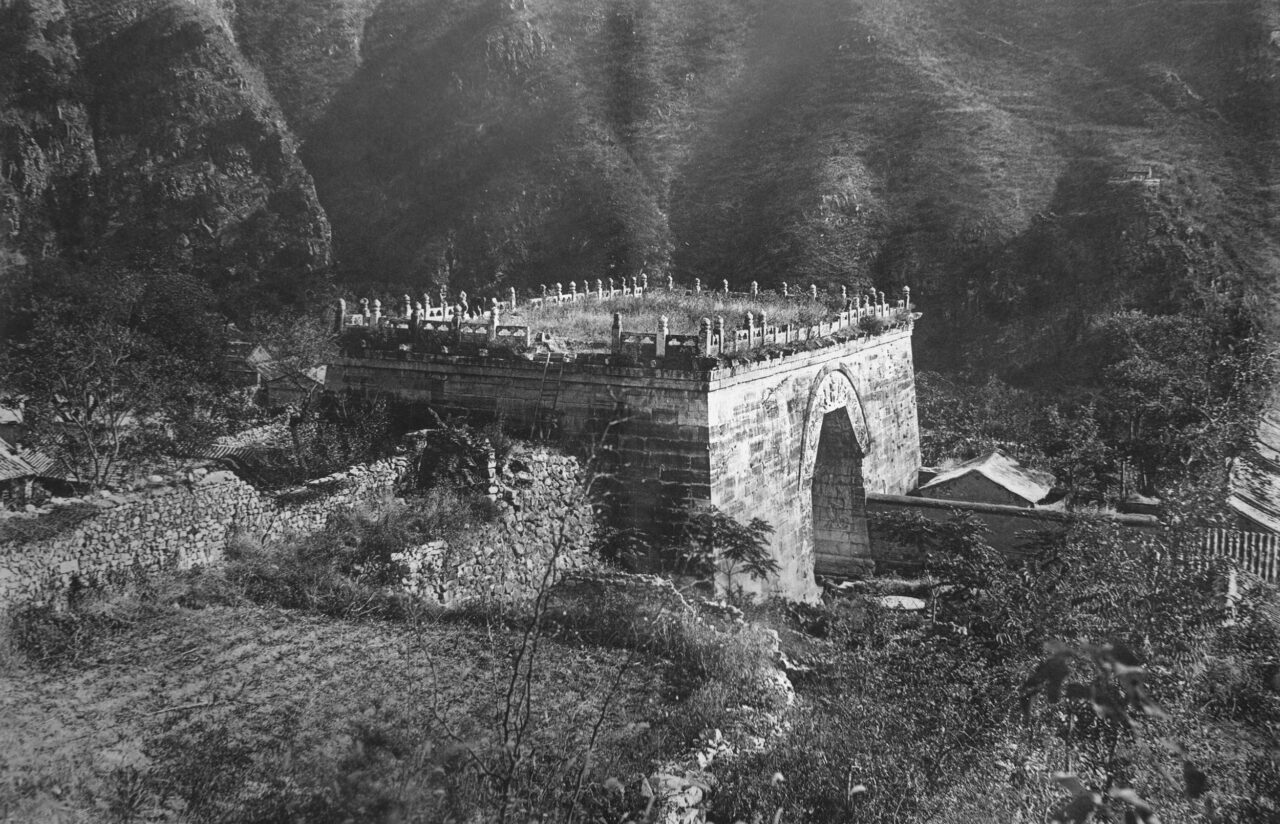

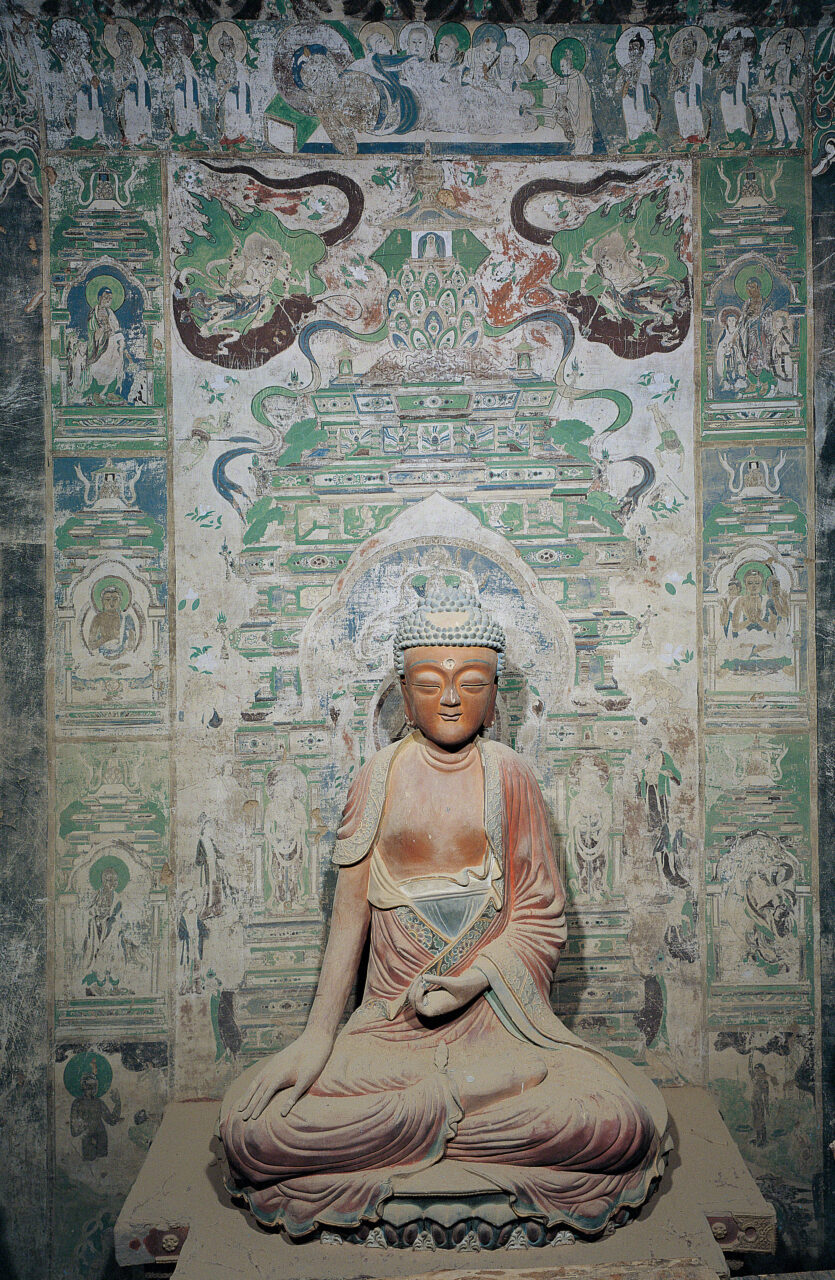

Stupas are monuments that initially contained cremated remains of Buddha Shakyamuni or important monks, his disciples, and subsequently other material and symbolic relics associated with the Buddha’s body, teaching, and enlightened mind. As representations of the Buddha’s presence in the world, stupas with their contents—texts, relics, tsatsas—continue to be important objects of Buddhist worship in their diverse forms of domed structures, multistoried pagodas, and portable sculptures. The original form of stupas was an earthen dome-shaped mound containing the remains in reliquary vessels or urns deposited within the innermost core. The dome would often be successively enlarged and surrounded by a path for a walk around in a clockwise direction and veneration (circumambulation)

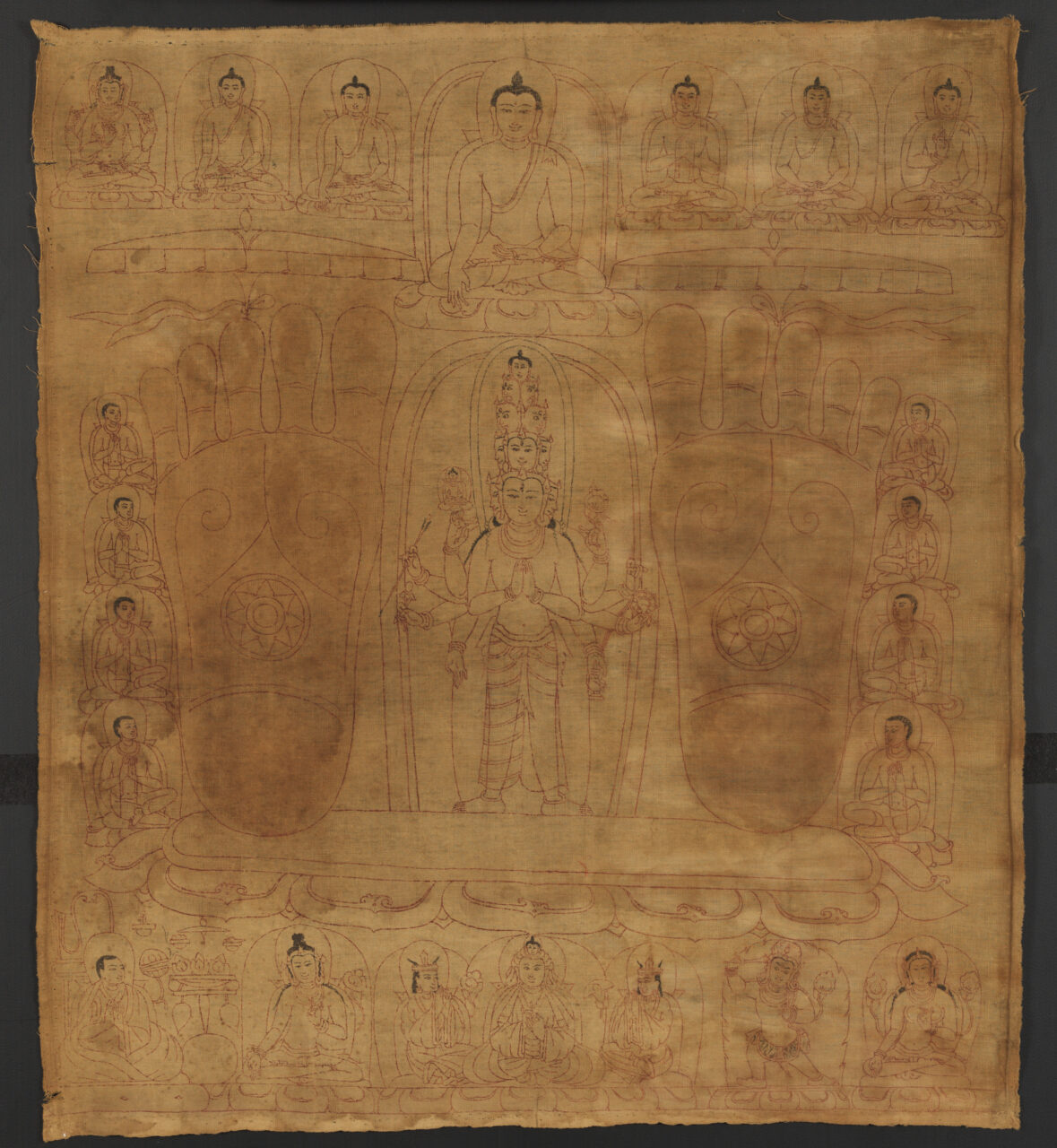

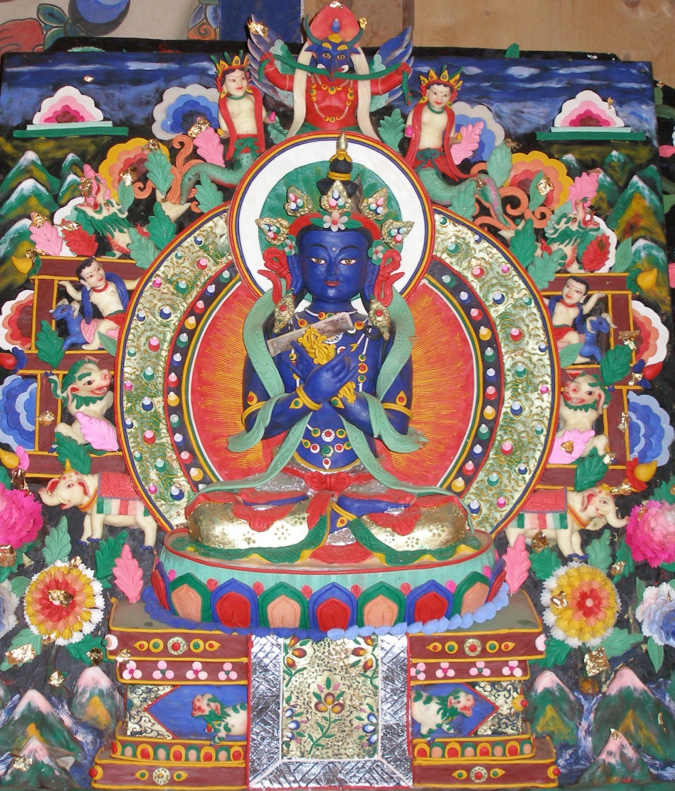

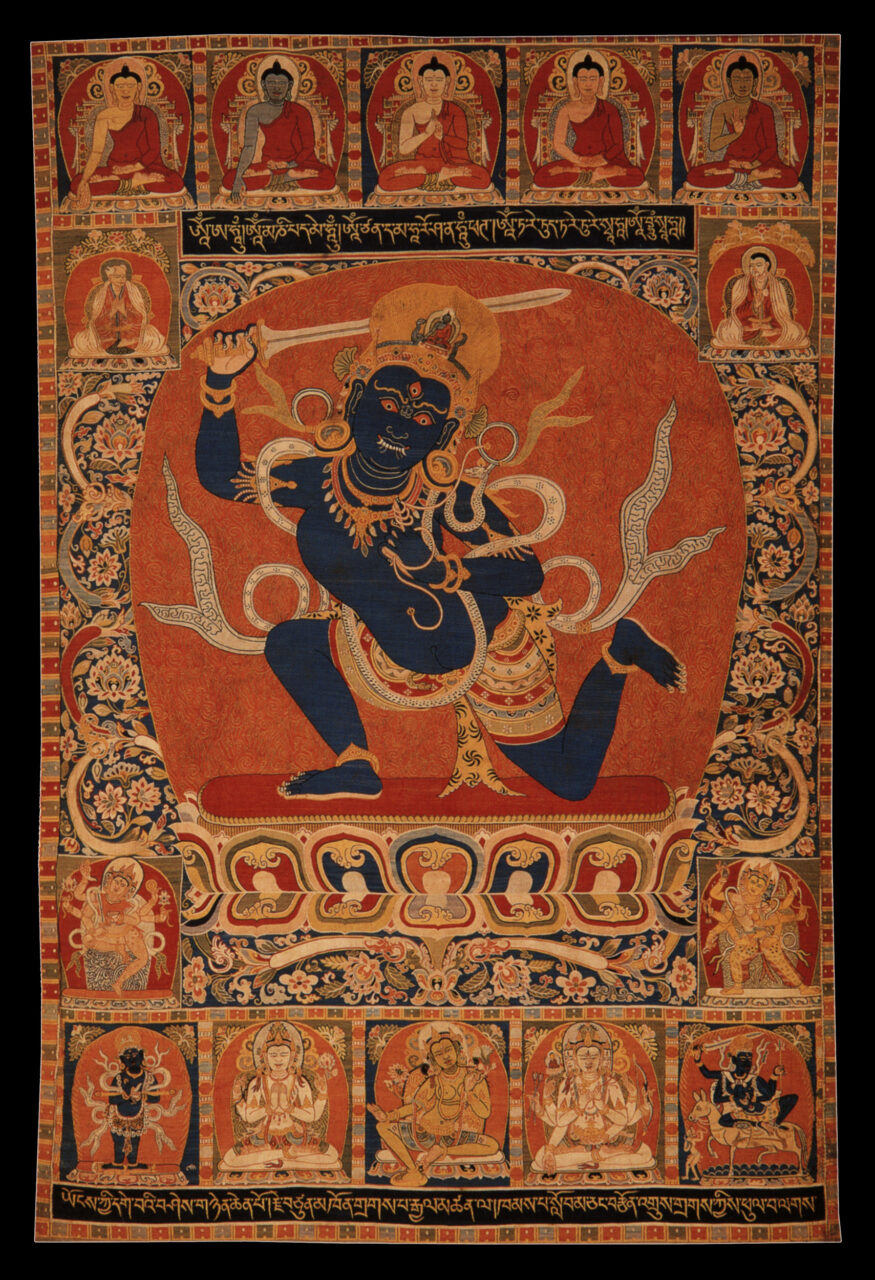

Tantra was a religious movement in India around the fifth to seventh centuries, and its practices are part of Buddhism and Hinduism. The word tantra also refers to texts which transmit tantric practices. In Buddhism, tantra is also called Vajrayana, “The Vajra Vehicle.” Tantric ritual and art are characterized by deity yoga, mandalas, mantras, abhisheka (initiation), wrathful deities, and ritual sexual union. In Hinduism, tantrism was often associated with the worship of Shiva and various goddesses (shakti). A practitioner of tantra is called a “tantrika.” Tantra is also a genre of texts that have been variously categorized. Most common is the division of tantras into four categories: Kriya Tantra, Charya Tantra, Yoga Tantra, and Highest Yoga Tantra.