A chakravartin is an ideal of Buddhist kingship, a universal ruler who supports the sangha and “turns the wheel of the Dharma.” Since the time of Emperor Ashoka (304–232 BCE), the archetypal chakravartin, many Buddhist rulers in history have been praised as chakravartins, or rulers who support Buddhism and help its spread through the expansion of his domains.

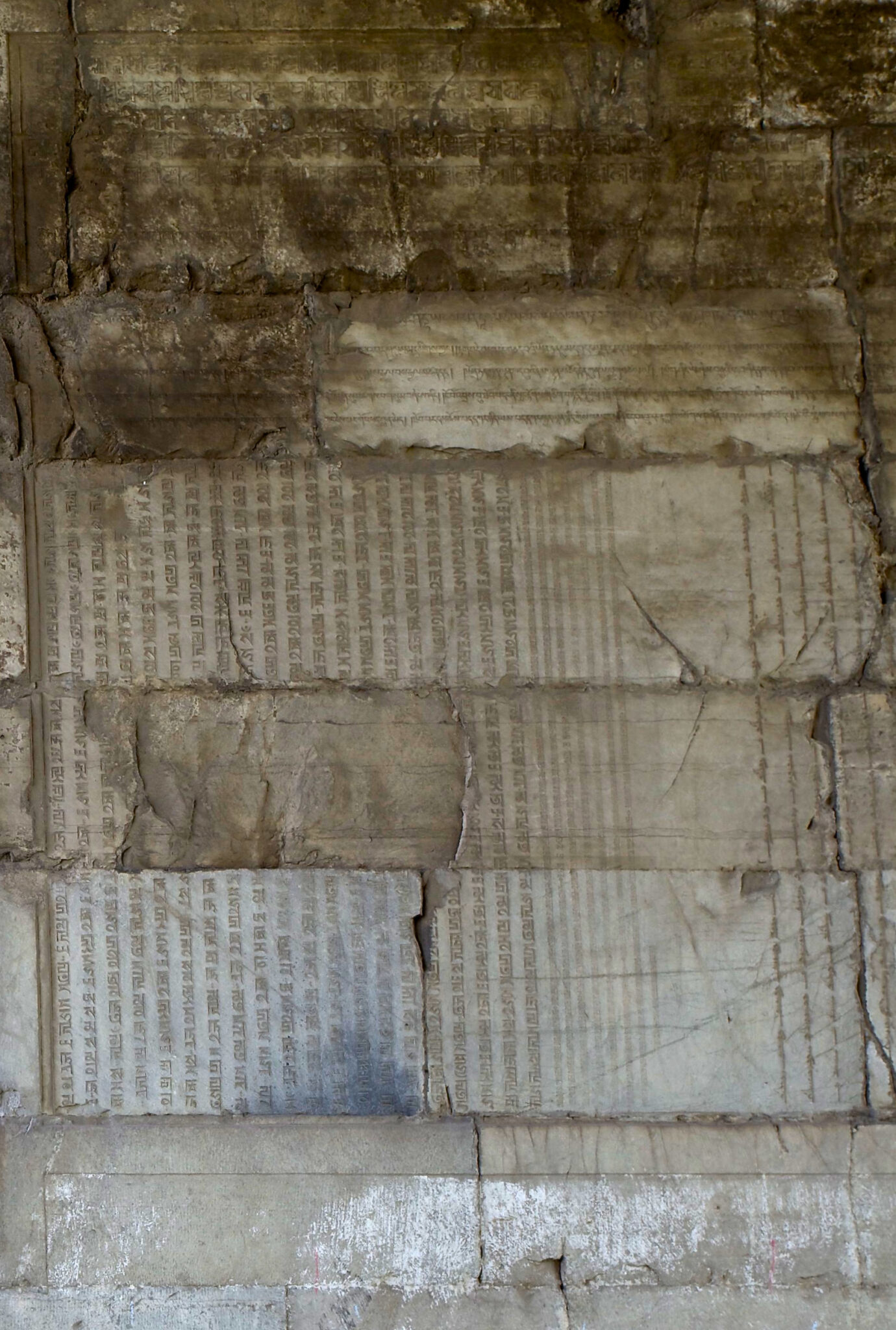

In Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, a dharani is a short, Sanskrit language text or spell-like formulas thought to have protective power when written or recited out loud, often as part of a ritual. Often inscribed on objects or at sacred sites, their power through the written physical presence is associated with long life, purification, and protection. Dharanis are similar to mantras, but usually longer. One important dharani is the Ushnishavijaya Dharani. The Pancharaksha is another important text that contains five dharanis of protection.

The Mongol Empire (ca 1206–1368) was the largest contiguous empire in world history, founded by Chinggis Khan (1162–1227), which at its height controlled most of Eurasia, from the Korean peninsula to Central Europe. The Mongols conquered the Tanguts in 1227 and absorbed Tibetan regions in the 1240s, granting power over central Tibet to the Sakya Buddhist hierarchs in what is characterized as a priest-patron relationship. In 1260, Qubilai Khan declared himself Great Khan, which was contested, fracturing the Mongol Empire into four independent regimes. Qubilai remained the ruler of most of Asia establishing the Yuan dynasty. Mongol rulers of Yuan, and the first six rulers the Ilkhanate in the Middle East, starting with its founder Hülegü, were also patrons of Tibetan Buddhism.

Historically, Tibetan Buddhism refers to those Buddhist traditions that use Tibetan as a ritual language. It is practiced in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, Ladakh, and among certain groups in Nepal, China, and Russia and has an international following. Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in two waves, first when rulers of the Tibetan Empire (seventh to ninth centuries CE), embraced the Buddhist faith as their state religion, and during the second diffusion (late tenth through thirteenth centuries), when monks and translators brought in Buddhist culture from India, Nepal, and Central Asia. As a result, the entire Buddhist canon was translated into Tibetan, and monasteries grew to become centers of intellectual, cultural, and political power. From the end of the twelfth century, Tibetans were exporting their own Buddhist traditions abroad. Tibetan Buddhism integrates Mahayana teachings with the esoteric practices of Vajrayana, and includes those developed in Tibet, such as Dzogchen, as well as indigenous Tibetan religious practices focused on local gods. Historically major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism are Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Geluk.

The Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) is the branch of the Mongol Empire in Asia. In 1260 when Qubilai Khan declared himself Great Khan, his realm included Mongolian, Chinese, Tangut, and Tibetan regions. In 1271 emperor Qubilai Khan proclaimed the Yuan dynasty on a Chinese model, employing Tibetan and Tangut monks. Tibetan Buddhism played an important role in the state, establishing a political model that would be emulated by later dynasties, including the Chinese Ming and Manchu Qing dynasties. The Mongols were major patrons of Tibetan institutions, and many Mongols converted to Tibetan Buddhism, though their interest declined with the fall of the empire.