In Hinduism, Hayagriva is a deity said to be an avatar of Vishnu, recognizable by his human body and horse’s head. In Vajrayana Buddhism, Hayagriva sometimes appears as a dharma protector, a meditational deity, a heruka, or an attendant to Avalokiteshvara. In Buddhist images he is recognizable by the small horse head(s) protruding from his hair on the top of his head.

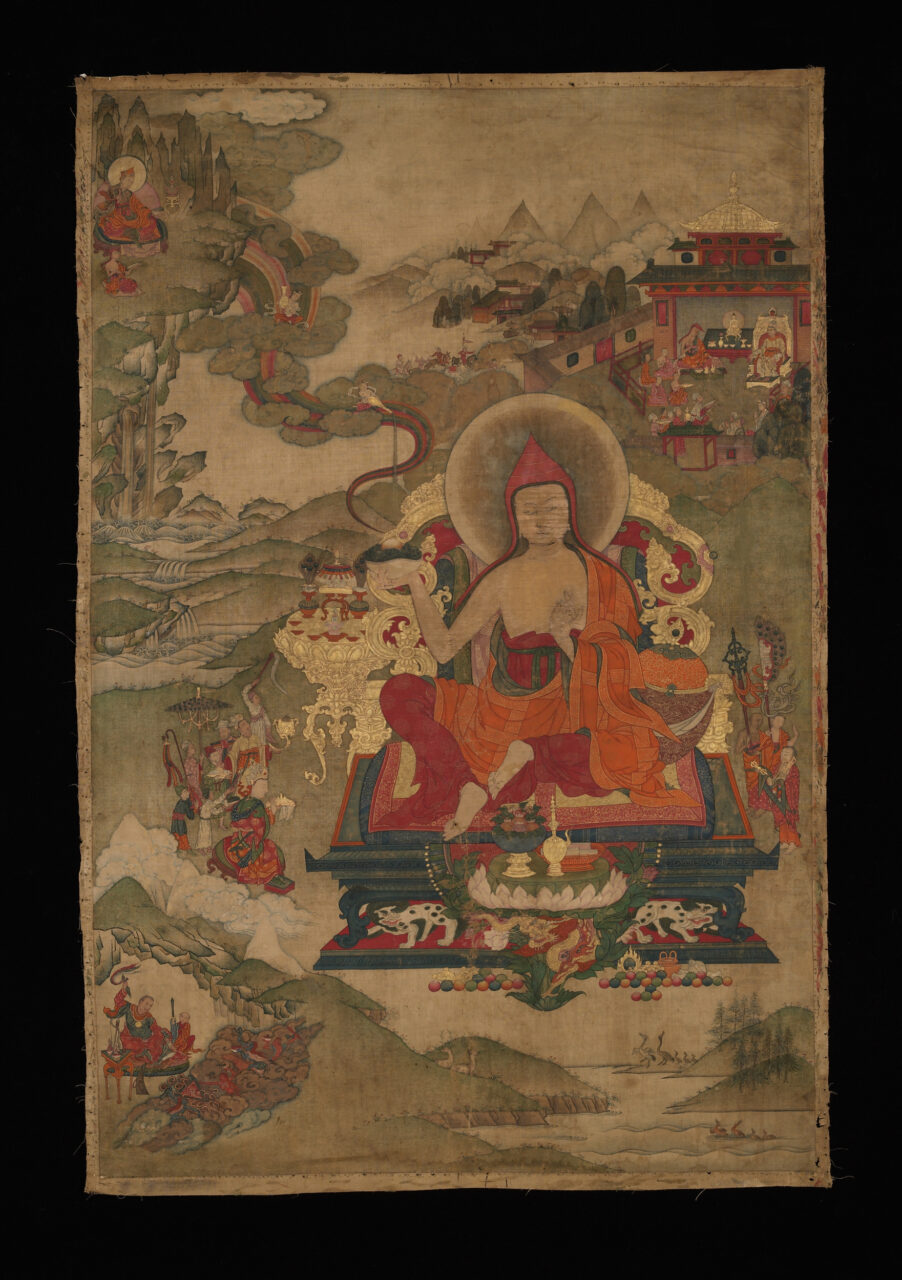

In the Himalayan context, iconography refers to the forms found in religious images, especially the attributes of deities: body color, number of arms and legs, hand gestures, poses, implements, and retinue. Often these attributes are specified in ritual texts (sadhanas), which artists are expected to follow faithfully.

The Nyingma are a tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. The Nyingma trace their lineages back to the first introduction of Buddhism into the Himalayas in the time of the Tibetan Empire, most importantly to the legendary Indian yogin Padmasambhava. The Nyingma are known for their “treasure revealers” (Tib. terton), lamas who travel the Himalayas, revealing ritual texts, objects, and hidden lands thought to be concealed within the Tibetan landscape. The Nyingma are also famed for the Dzogchen teachings, a set of meditative practices focused on the bardo states, and the nature of the mind as pure, self-arising consciousness. Unlike other Buddhist traditions, many Nyingma practitioners are not celibate and can marry, raise families, and grant Vajrayana initiations and teachings to their children.

The Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism holds that gurus of the past like Padmasambhava concealed texts, objects, and even hidden lands (Tib. beyul) throughout the Himalayan landscape, meant for later generations to discover at the time the teachings are needed. Tantric practitioners and yogis who discover these treasures are called terton, or “treasure revealers.” Treasure revealers can also uncover “mind-treasures,” revealed to them by deities or lineage masters in dreams and visions. There are treasure-revealers in the Bon tradition as well.

In Mahayana Buddhism, every buddha is thought to have three bodies. The dharma body (dharmakaya) is the primordial, empty, true nature of all buddhas. The enjoyment body (sambhogakaya) is the buddha as he exists in his exalted pure realm and mandala, surrounded by bodhisattvas. In images, these bodies can be recognized by their jewel ornaments and crown (like Amitayus). The emanation bodies (nirmanakaya) are the innumerable forms or manifestations of the buddhas who appear in the world or on earth in order to teach sentient beings the path to freedom from suffering. In images, emanation bodies can often be recognized by their monk’s robes (like Amitabha).

Historically, Tibetan Buddhism refers to those Buddhist traditions that use Tibetan as a ritual language. It is practiced in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, Ladakh, and among certain groups in Nepal, China, and Russia and has an international following. Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in two waves, first when rulers of the Tibetan Empire (seventh to ninth centuries CE), embraced the Buddhist faith as their state religion, and during the second diffusion (late tenth through thirteenth centuries), when monks and translators brought in Buddhist culture from India, Nepal, and Central Asia. As a result, the entire Buddhist canon was translated into Tibetan, and monasteries grew to become centers of intellectual, cultural, and political power. From the end of the twelfth century, Tibetans were exporting their own Buddhist traditions abroad. Tibetan Buddhism integrates Mahayana teachings with the esoteric practices of Vajrayana, and includes those developed in Tibet, such as Dzogchen, as well as indigenous Tibetan religious practices focused on local gods. Historically major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism are Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Geluk.