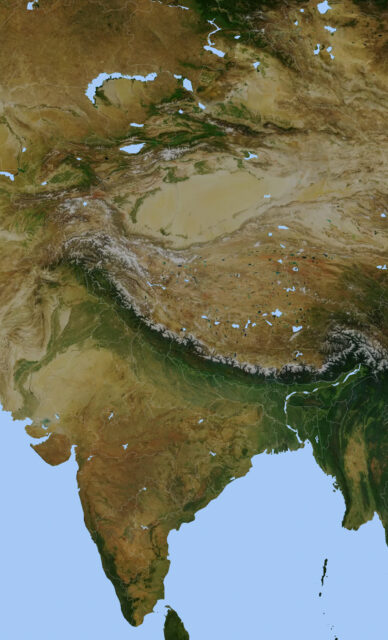

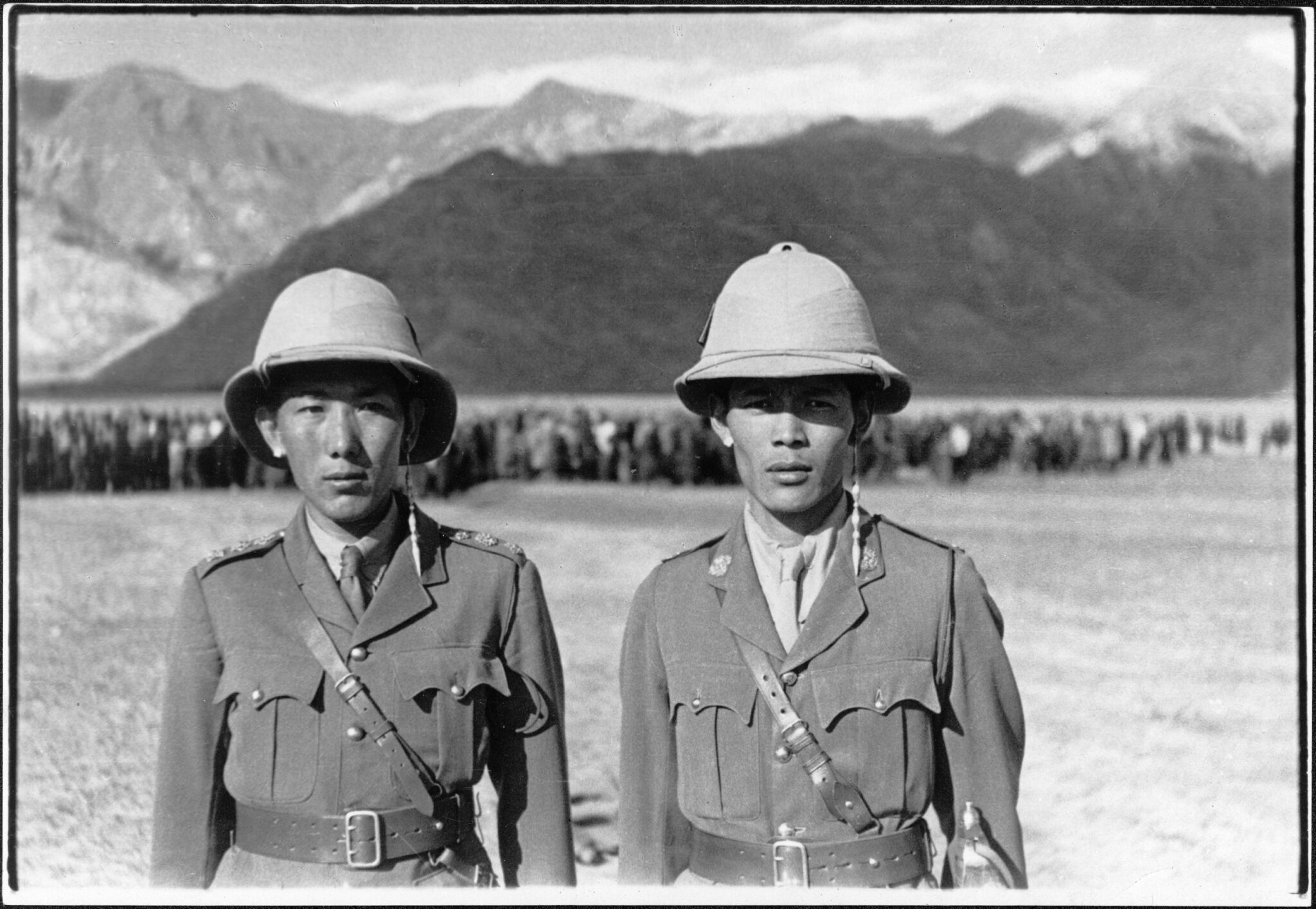

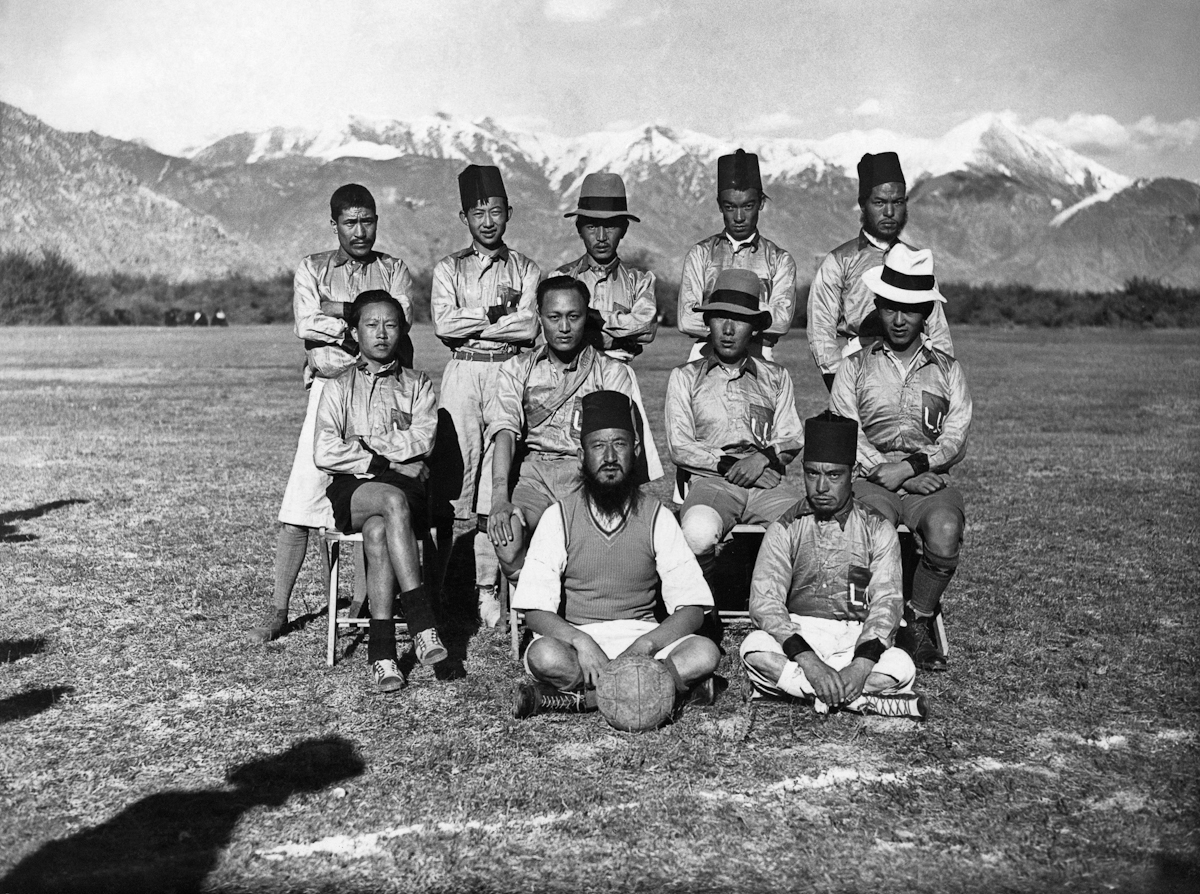

The British Empire was the largest empire in world history, ruling almost a quarter of the world’s land area and population at its height in the mid-twentieth century. The British achieved hegemony in India after the Battle of Plassey in 1757, and soon came to rule large areas of the Himalayas, including Kashmir and Ladakh. Several small Himalayan kingdoms, including Nepal, Bhutan, and Sikkim, were allowed to maintain semi-independence as buffer-states against Qing-controlled Tibet. The British briefly invaded Tibet in 1903–1904. After the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1912, the British became a major cultural and military influence on the Ganden Podrang government in Lhasa. India achieved independence in 1947, ending British rule in the Himalayas.

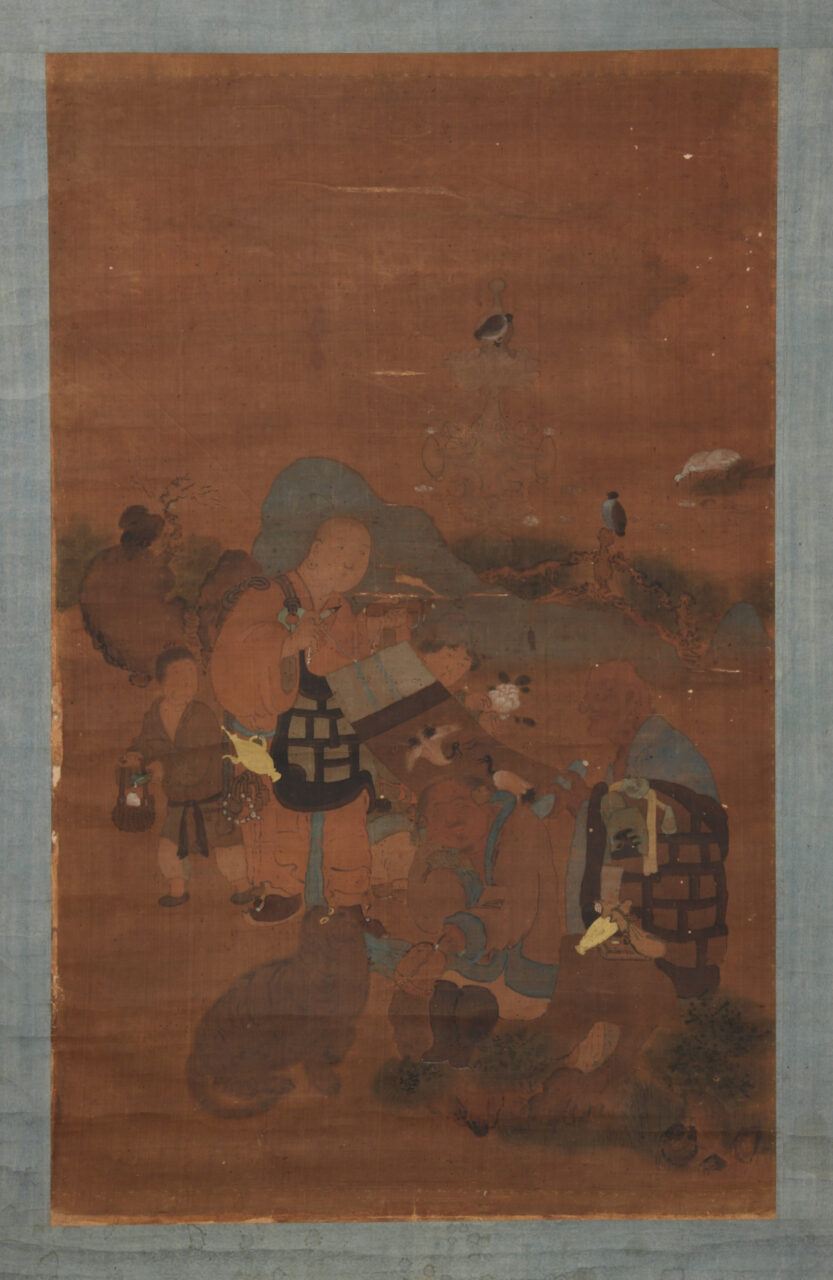

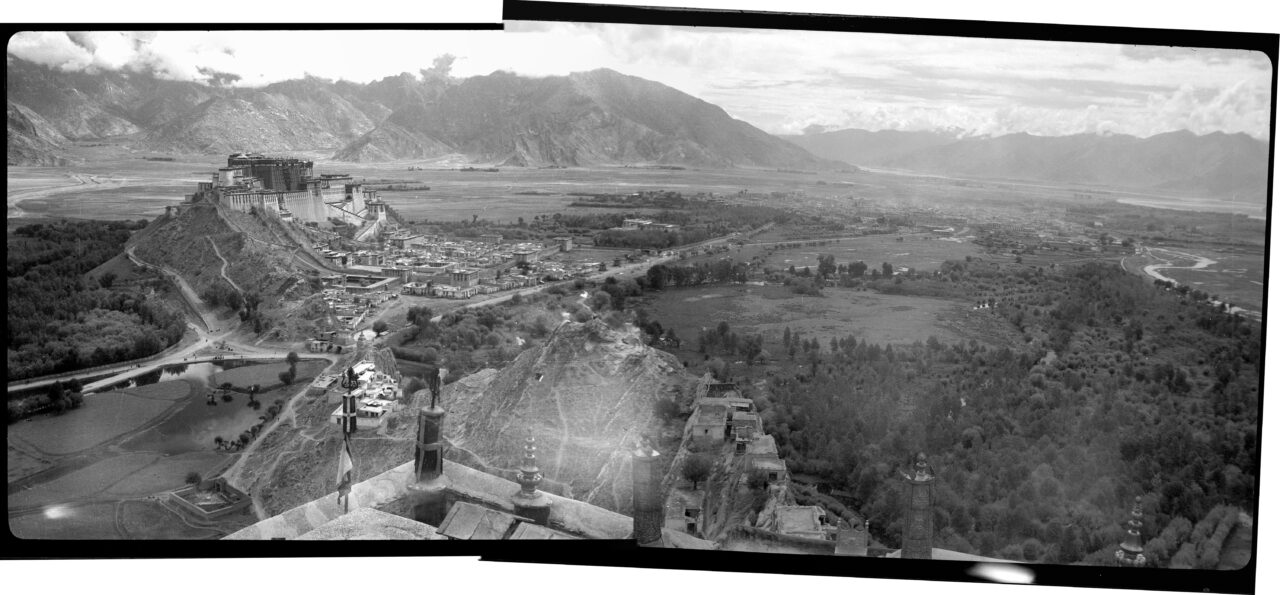

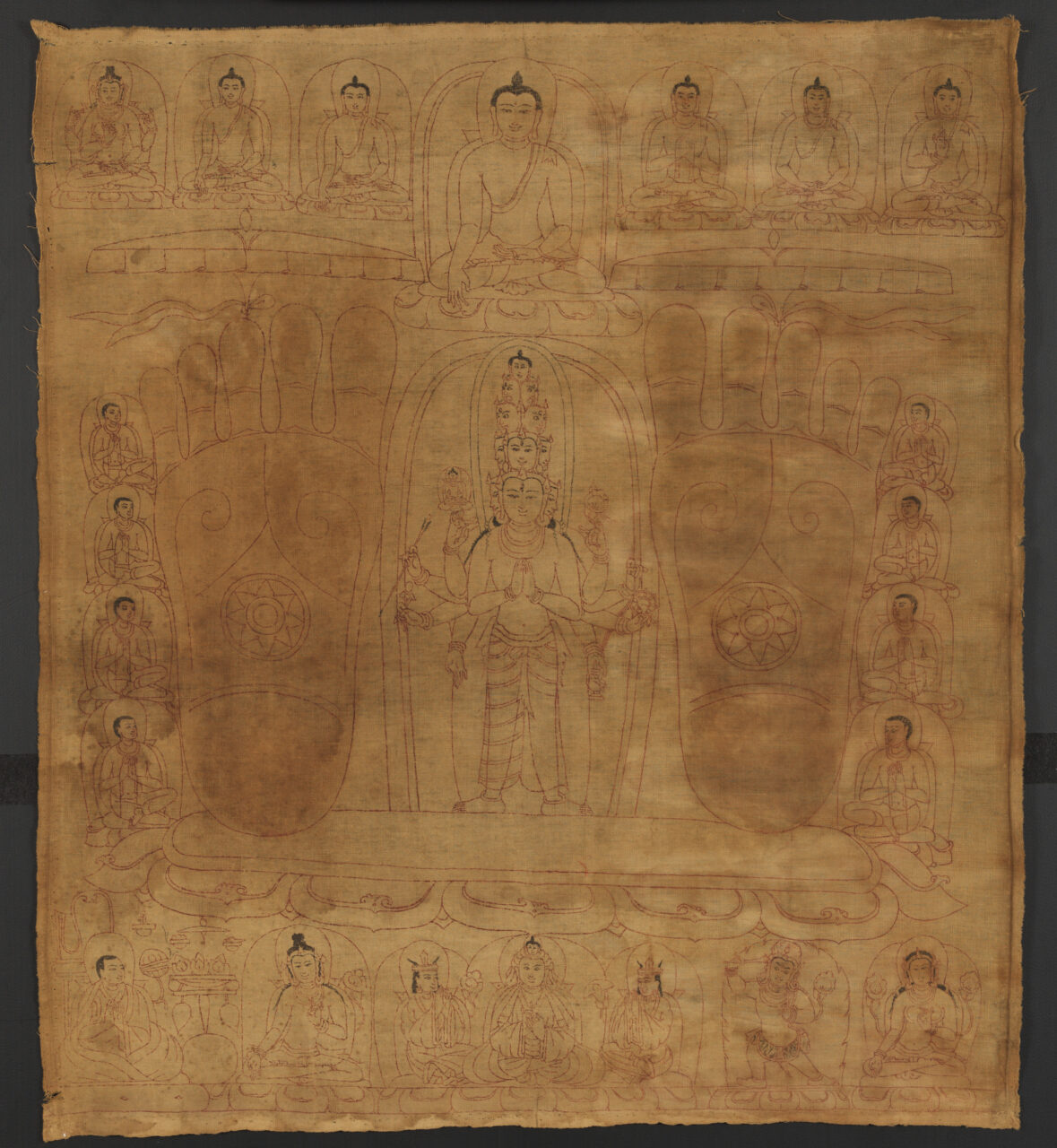

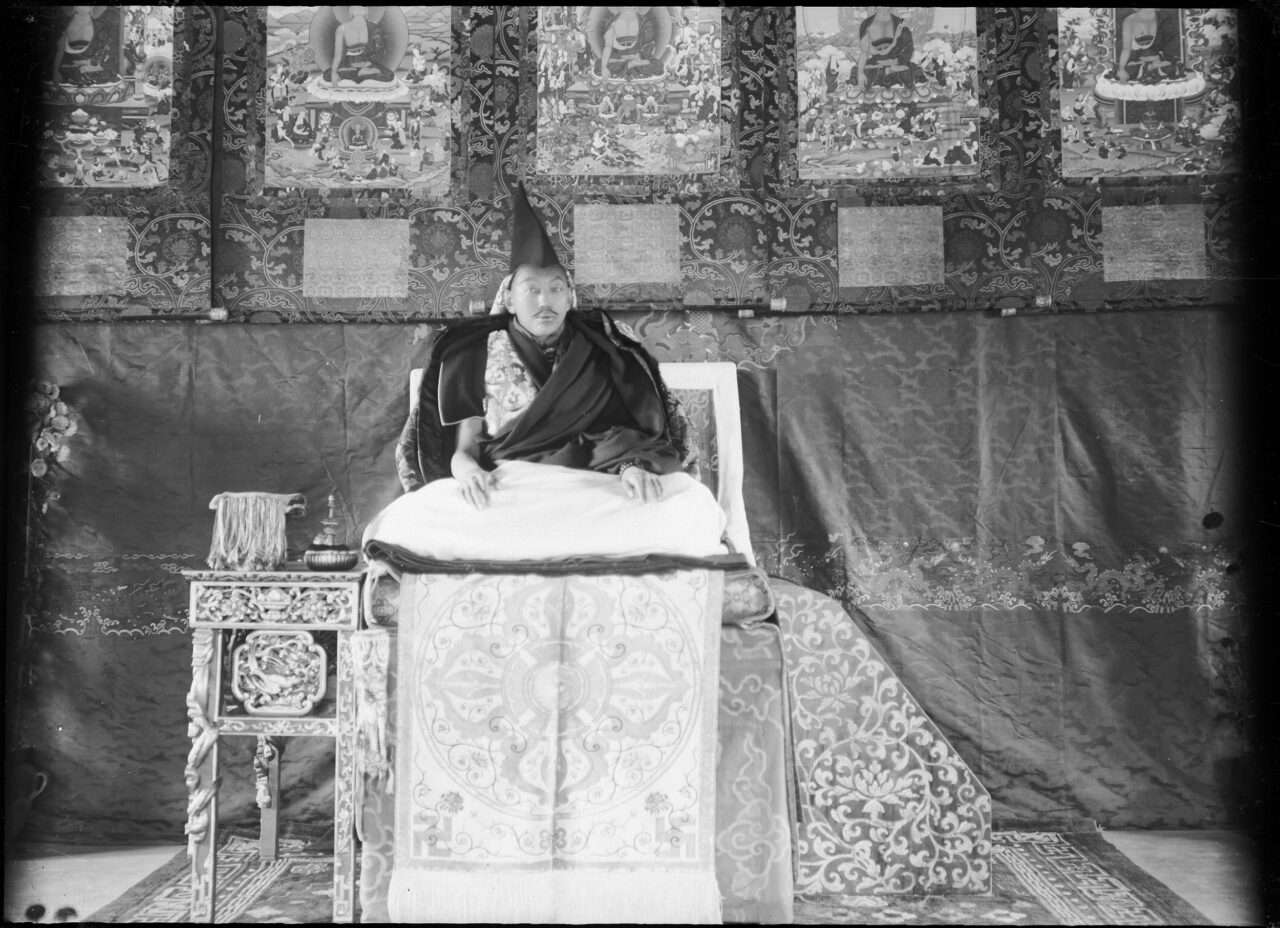

The Dalai Lamas are a tulku lineage that has played a central role in Tibetan history for the last five hundred years. In 1577 a Mongol khan gave the Geluk monk Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588) the title “Dalai Lama,” combining the Mongolian word for ocean, dalai (a reference to the depth of his knowledge), and the Tibetan word for guru, lama. Later, two previous incarnations were retroactively identified. The fifth incarnation, Ngawang Gyatso (1617–1682), allied with another Mongol khan to unite most of the Tibetan Plateau, forming the Ganden Podrang government that would govern Tibet until 1959. Since the Communist takeover, the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama has lived in exile at Dharamshala in India. The Dalai Lamas are understood to be emanations of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

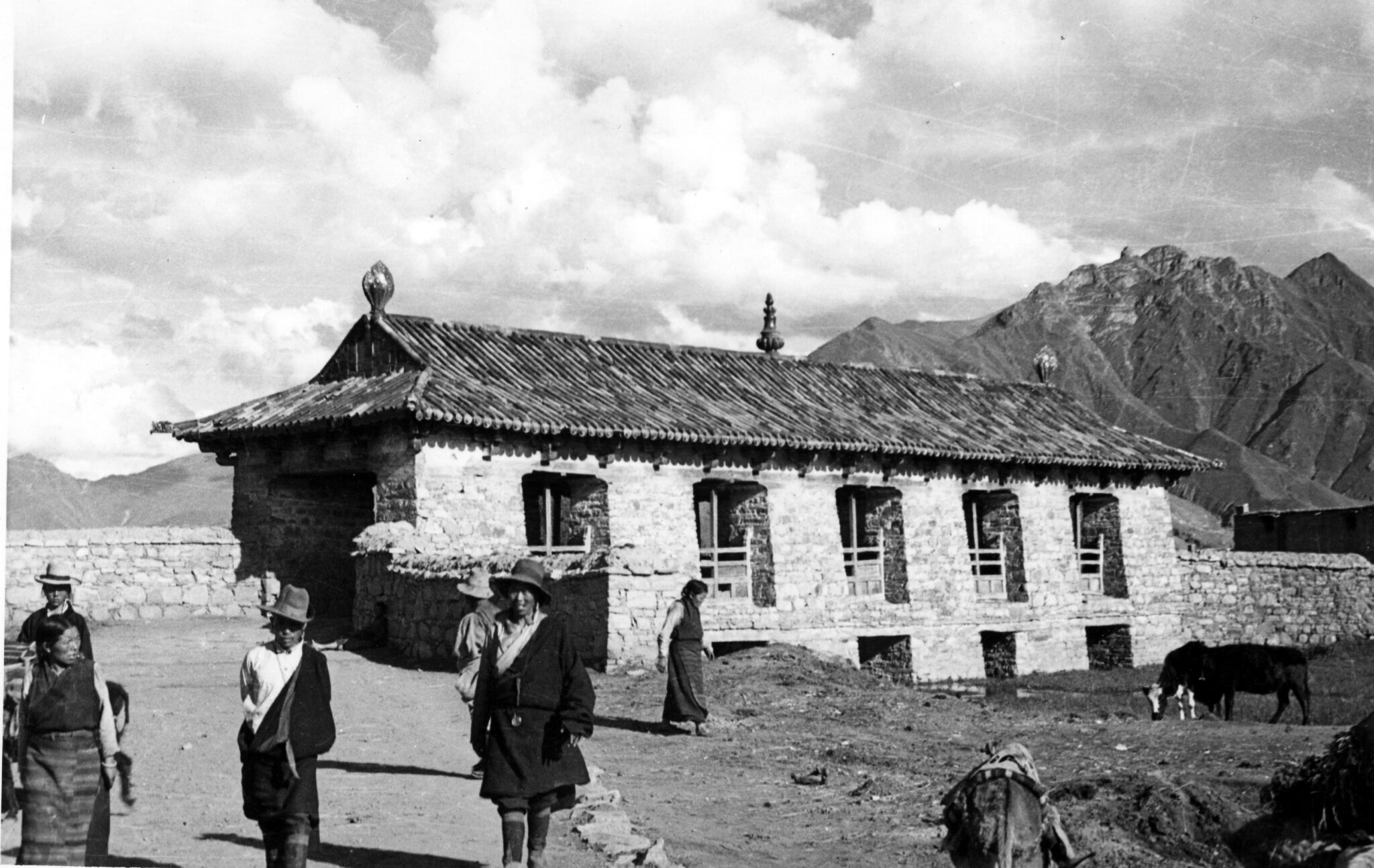

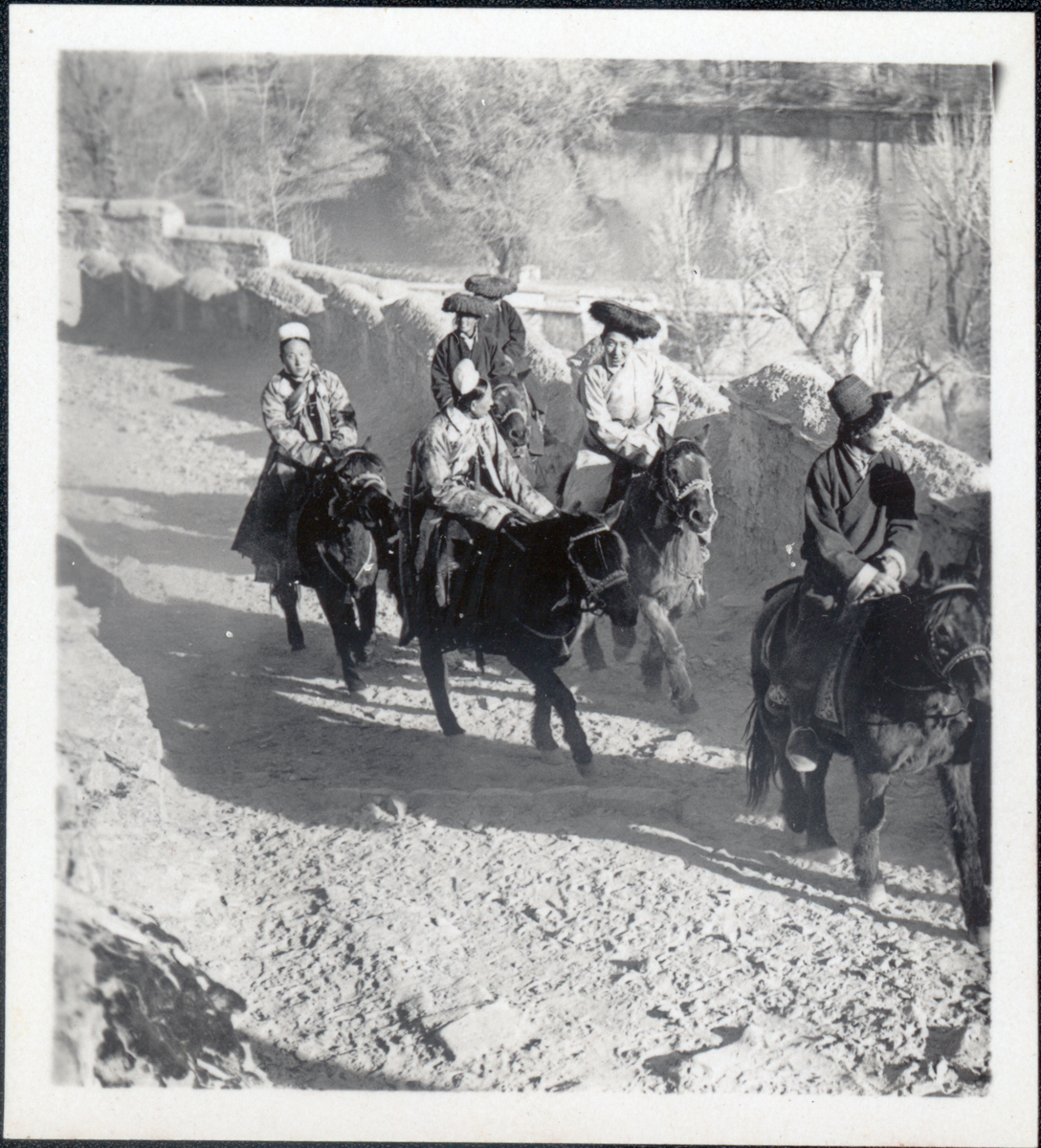

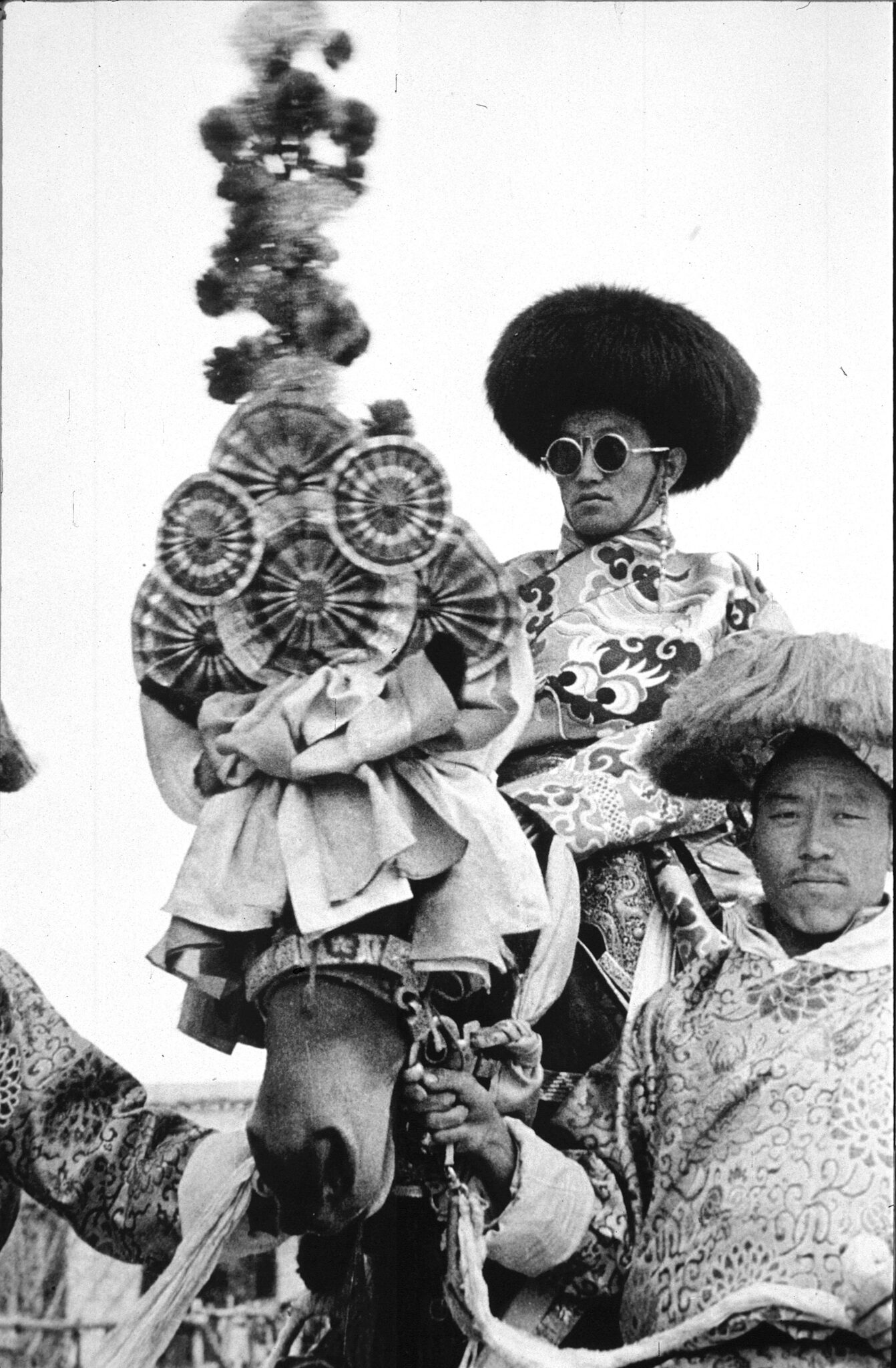

The Ganden Podrang was the government system that ruled Central Tibet, in one form or another, from 1642 to 1959. Headed by the Dalai Lamas, the Ganden Podrang had a dual system that included both powerful Geluk monastic officials and secular members of the Central Tibetan noble families. From the eighteenth century onward, the Ganden Podrang had a central governing council called the “kashag,” or “parliament.”

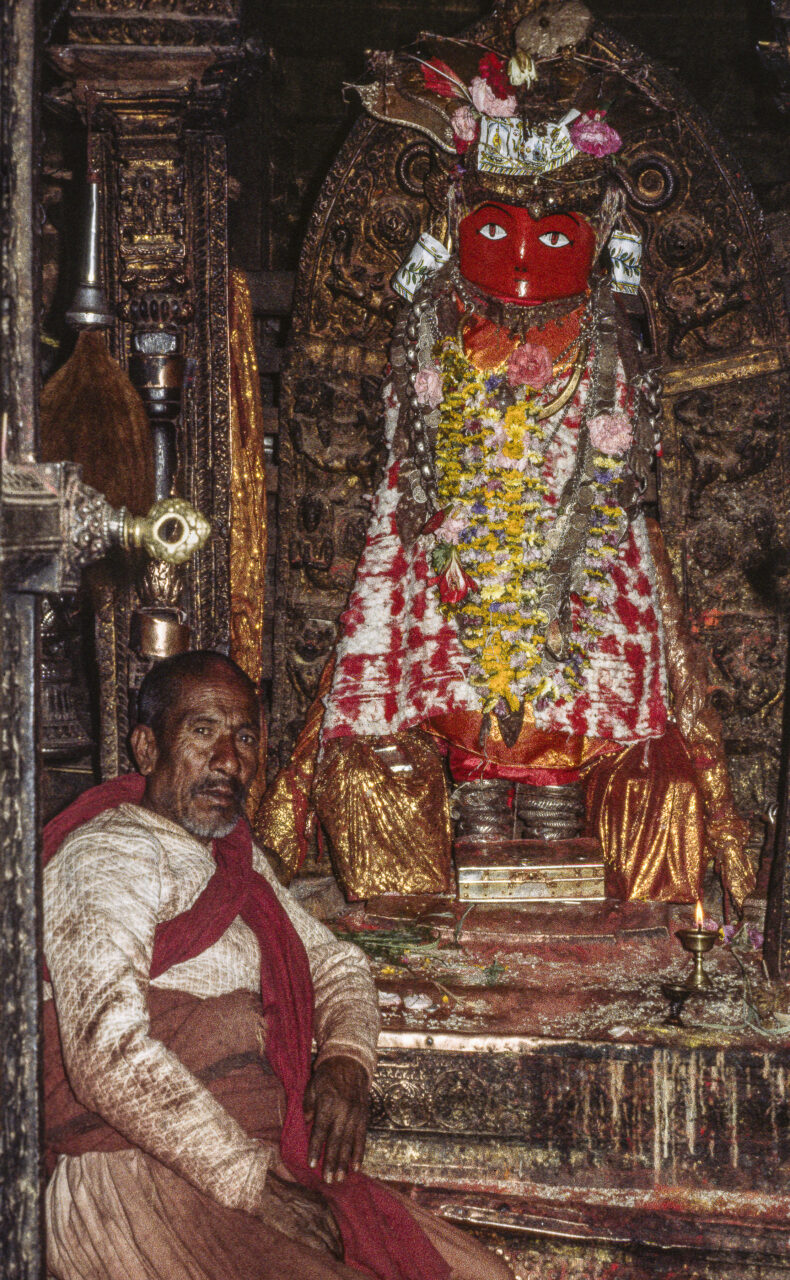

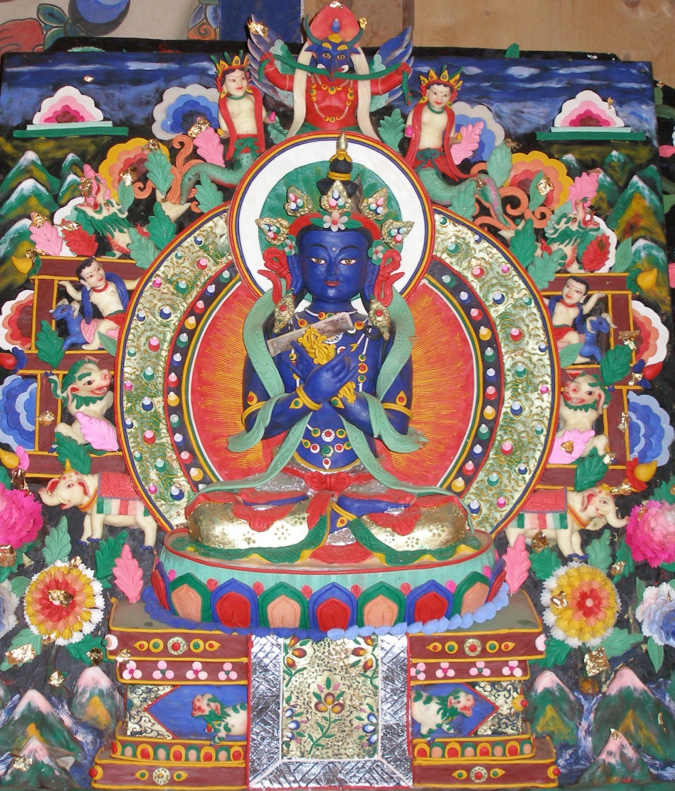

Gilding is a metalworking technique in which a fine golden surface is applied over a statue made of bronze. In Newar metalworking workshops, gilding is typically done with fire and mercury, which gives sculptures a warm finish (but is poisonous for their makers). In Tibetan contexts sometimes gold dust is mixed with glue and applied with a brush (often called “cold gold”), especially to a deity’s face to gain merit.

Inlay is a decorative technique of creating a depression in a surface and then filling it with some other material. Metal can be inlaid with precious stones or glass, or more precious forms of metal, for instance, brass inlaid with silver and copper. Wood can be inlaid with silver, or other metal and conch. Tibetans tend to favor turquoise inlay while the Newars employ a range of colored glass and semi-precious stones.