Buddhism is founded on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, who lived sometime between the sixth and fourteenth century BCE in northern India. Buddhists believe that sentient life is a cycle of suffering and rebirth, but that if one achieves a state of awakening or nirvana, it is possible to escape this cycle. Buddhists refer to the Buddha’s teachings as the Dharma. There are many different traditions or denominations of Buddhism, including Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. Scholars also discuss regional traditions, such as Indian Buddhism, Newar Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Chinese Buddhism, and so on.

The kirtimukha is a symbolic element in South Asian art—a mask-like face of a fanged beast. Kirtimukhas are usually placed above other elements, such as upper portions of the carved portals, throne backs, or as a row adorning the upper portions of the painted walls.

“Silk Roads” is a term broadly used to describe the long-distance trade routes across Central Asia that connected the Indian Subcontinent with East Asia and the Mediterranean world. These trade routes were highly important in transmitting both art and ideas across the Asian continent, including the Buddhist religion. There were many “silk roads”—some crossed the deserts of Central Asia, other maritime routes also connected Europe, the Middle East, Africa, South, Southeast, and East Asia.

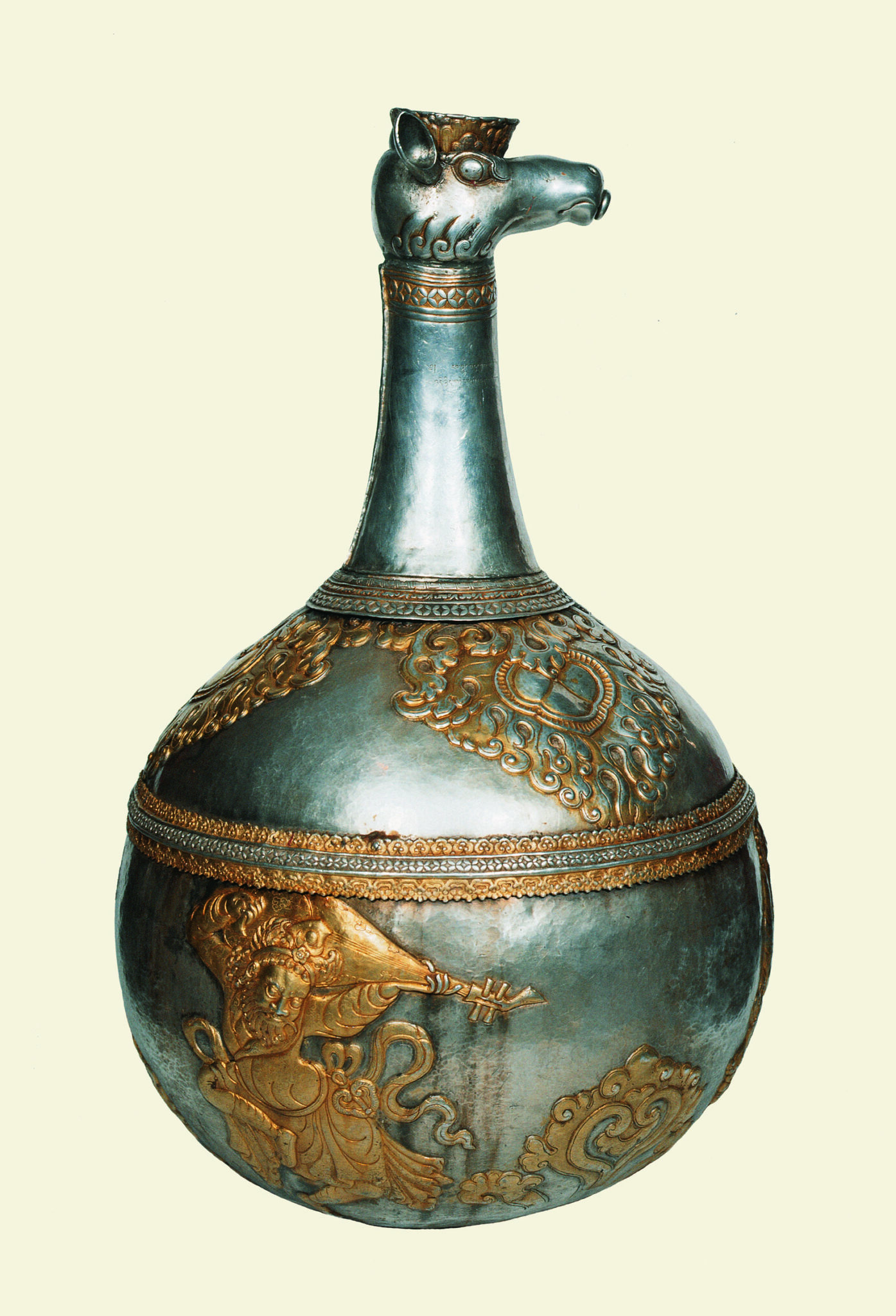

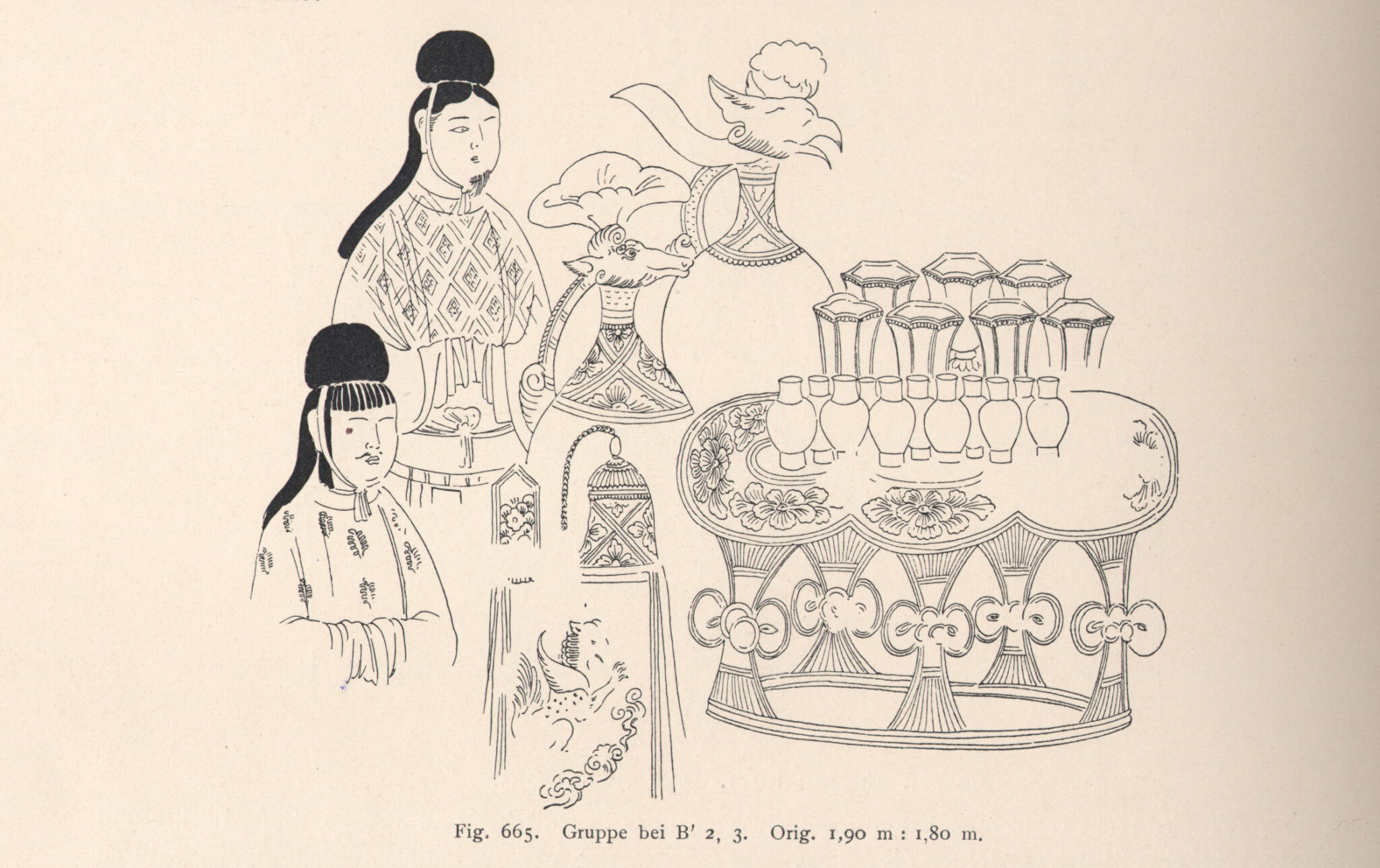

The Sogdians were a historic Central Asian people who originated in the region of present-day western Tajikistan and surrounding areas of Uzbekistan and Afghanistan. The Sogdians spoke a language related to Persian and were major players in the medieval Central Asian caravan trade, forming crucial contacts between Persia, China, and Tibet. They were important conduits of artistic traditions and material culture, including Sasanian metalwork and Central Asian silk weaving. After the Arab conquest of their homeland in the eighth century, the Sogdians mostly disappeared from history, although the Sogdian language is still spoken by a few thousand people in the mountains of Tajikistan.

In the early seventh century, a line of kings from the Yarlung Valley united disparate people on the Tibetan Plateau into a powerful, centralized state. With their capital at Lhasa, these kings proclaimed themselves emperors, or tsenpo. Their armies conquered much of the Himalayas, Central Asia, and western China. Tibetans developed a written script for the Tibetan language and Buddhism was adopted as a state religion. The conversion to Buddhism was contested by an indigenous group of ritualists called Bon, creating political turmoil. After the assassination of emperor Langdarma in 842, the Tibetan empire fragmented and collapsed. Nevertheless, the myths and memories of the empire continue to be a central part of Tibetan identity.

Turkic languages. The Old Uyghur Empire was a semi-nomadic Buddhist and Manichaean state that ruled in modern-day Mongolia between roughly the 740s and 840s CE. After the destruction of the Uyghur Empire by the Kyrgyz, many Uyghurs fled to the oasis city-states of eastern Central Asia, including Dunhuang. These Uyghurs played an important role in the rise of the Mongol Empire in the thirteenth century, when they provided scribes for the imperial administration. Much later, the word “Uyghur” came to refer to the Turkic-speaking Muslims who live in what is now Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in the far northwest of China.