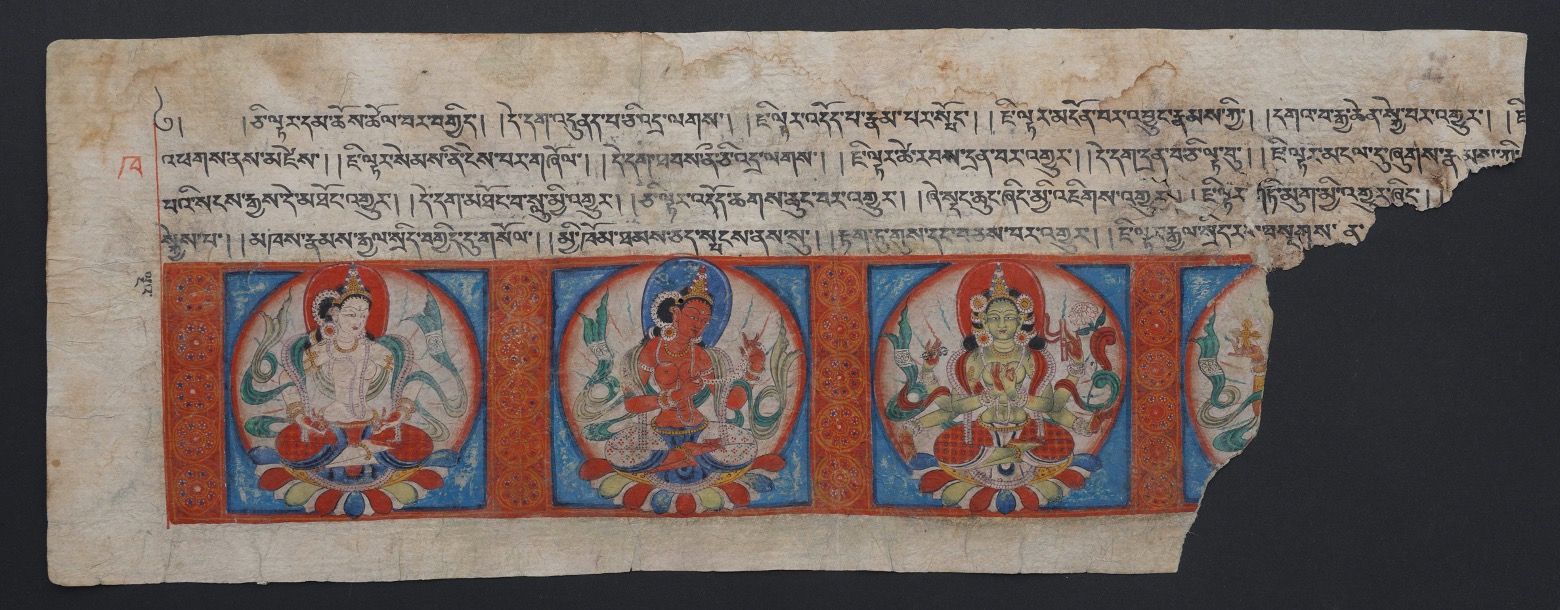

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a being who has made a vow to become a buddha or awakened. In the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, many bodhisattvas are understood as deities with enormous powers who delay their final enlightenment, remaining in the phenomenal world to help suffering beings. Among such great bodhisattvas are Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Maitreya.

The Cultural Revolution was a political and social movement in communist China from 1966 to 1976. During this time, traditional culture across all of China came under violent attack, and almost all religious institutions were shut down and many were physically destroyed. In minority areas, ethnic differences and indigenous cultural practices, such as use of Tibetan language or dress, were seen as backward and subject to persecution, adding an additional racial dimension. Hundreds of thousands of Tibetans fled to India or Nepal, and many Himalayan artworks were destroyed or scattered abroad.

A dhoti is a traditional Indian lower-body garment for men, made of a cloth wrapped around the waist and tucked through the legs from the back.

In Buddhist context, donor is a person who contributes to or commissions a religious work of art. This act is intended to increase merit on behalf of the benefactor and is dedicated to the benefit of all. It is also usually done for a specific purpose, such as longevity, prosperity, or well-being; to advance religious practice; or to ensure a good rebirth of a deceased relative, teacher, or friend. A similar practice is also known in Hinduism and Bon.

An illuminated manuscript is one that is adorned with images, designs, and decorative text. Unlike an “illustrated” text, the images in an illuminated text don’t necessarily show scenes from the story of the text.

Sutras are written down words spoken by the Buddha Shakyamuni, narrated by his disciples. Sutra texts comprise the foundation of the textual canon of all Buddhist traditions. Sutras generally begin with the words, “Thus have I heard,” and continue to describe the place, time, and context in which the Buddha gave the teaching. Important Mahayana sutras include the Avatamsaka Sutra and the Prajnaparamita Sutras, as well as many others. Other important types of Buddhist text are avadanas, dharanis, as well as tantras.