Bon is an indigenous religion of Tibet. Originally, Bon were a group of non-Buddhist ritual specialists in the court of the Tibetan emperors. From the eleventh century onward, an organized religion called Yungdrung Bon, or “Eternal Bon,” took shape. Yungdrung Bon developed in dialogue with Buddhism, incorporating deities called buddhas, scriptures modeled on the Buddhist canon, monks, and the establishment of monasteries. Followers of Yungdrung Bon trace their own origins to a founder called Tonpa Shenrab, who arrived from the semi-mythical land of Zhangzhung in western Tibet. The word “Bon” can also refer to the many non-organized indigenous religious practices, including the worship of mountain deities and making namkha. A follower of Bon is called a Bonpo.

The swastika is an ancient Eurasian symbol, found in rock carvings since prehistoric times. In Hinduism, Buddhism, and Bon, the swastika is a common and auspicious decorative design, symbolizing the motions of the sun, the wheel of reincarnation, and the eternal nature of the teachings. In Tibetan, it is yungdrung (“Eternal”), the principal religious symbol of the Bon religion, and the organized system of Bon that emerged in dialogue with Buddhism is generally referred to as Yungdrung Bon. The strongly negative association of this design in Western countries is due to its appropriation by the twentieth-century Nazis as a symbol of their racial theories.

Historically, Tibetan Buddhism refers to those Buddhist traditions that use Tibetan as a ritual language. It is practiced in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, Ladakh, and among certain groups in Nepal, China, and Russia and has an international following. Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in two waves, first when rulers of the Tibetan Empire (seventh to ninth centuries CE), embraced the Buddhist faith as their state religion, and during the second diffusion (late tenth through thirteenth centuries), when monks and translators brought in Buddhist culture from India, Nepal, and Central Asia. As a result, the entire Buddhist canon was translated into Tibetan, and monasteries grew to become centers of intellectual, cultural, and political power. From the end of the twelfth century, Tibetans were exporting their own Buddhist traditions abroad. Tibetan Buddhism integrates Mahayana teachings with the esoteric practices of Vajrayana, and includes those developed in Tibet, such as Dzogchen, as well as indigenous Tibetan religious practices focused on local gods. Historically major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism are Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Geluk.

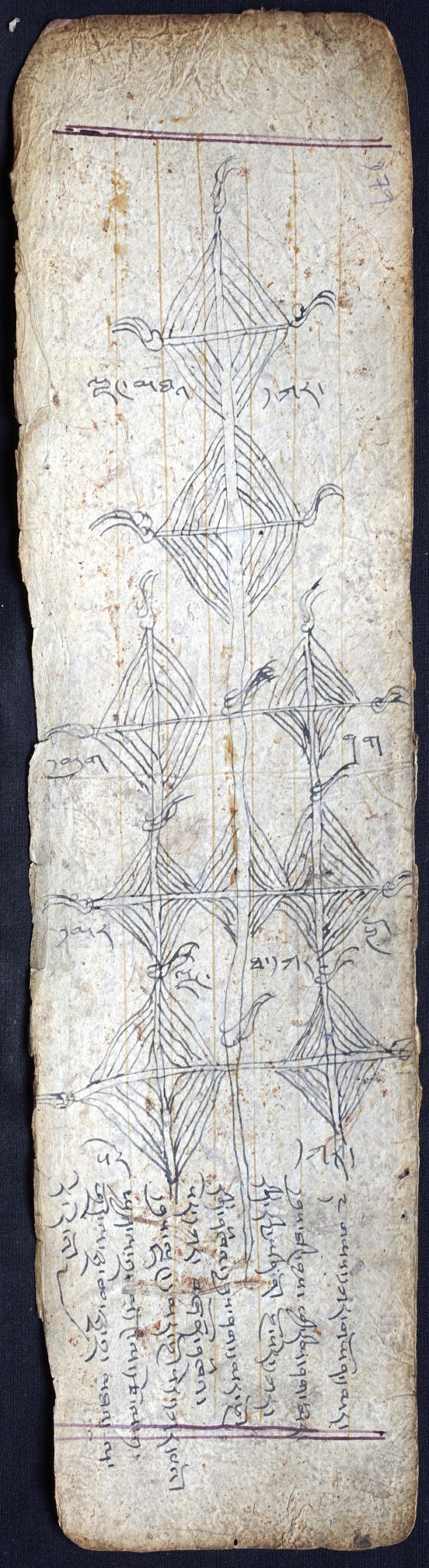

In Tibetan Buddhism and Bon, a torma is a sculpture made from butter and barley dough that is usually dyed. Tormas are used for a variety of purposes in rituals, and can be offerings to the gods, or consecrated as receptacles of divine power. In exorcistic rituals, evil forces are invited into the tormas, which are then brought outside of the settlement and destroyed. These tormas can be understood as ransom in exchange for victims plagued by spirits, or as a substitute for animal sacrifice. Some monasteries have traditions of making huge, beautifully decorated tormas, which are viewed by pilgrims at festivals like the Monlam Chenmo. Tormas can be figurative (images that depict the gods or other scenes), or they can be aniconic (symbolic shapes).